2019 Hazelwood Jessica 1240

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadith and Its Principles in the Early Days of Islam

HADITH AND ITS PRINCIPLES IN THE EARLY DAYS OF ISLAM A CRITICAL STUDY OF A WESTERN APPROACH FATHIDDIN BEYANOUNI DEPARTMENT OF ARABIC AND ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Glasgow 1994. © Fathiddin Beyanouni, 1994. ProQuest Number: 11007846 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007846 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 M t&e name of &Jla&, Most ©racious, Most iKlercifuI “go take to&at tfje iHessenaer aikes you, an& refrain from to&at tie pro&tfuts you. &nO fear gJtati: for aft is strict in ftunis&ment”. ©Ut. It*. 7. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................4 Abbreviations................................................................................................................ 5 Key to transliteration....................................................................6 A bstract............................................................................................................................7 -

Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban

Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for University Honors with Distinction by, Brandon Smith May 2005 Oxford, OH ABSTRACT AFGHANISTAN, 1989-1996: BETWEEN THE SOVIETS AND THE TALIBAN by, BRANDON SMITH This paper examines why the Afghan resistance fighters from the war against the Soviets, the mujahideen, were unable to establish a government in the time period between the withdrawal of the Soviet army from Afghanistan in 1989 and the consolidation of power by the Taliban in 1996. A number of conflicting explanations exist regarding Afghanistan’s instability during this time period. This paper argues that the developments in Afghanistan from 1989 to 1996 can be linked to the influence of actors outside Afghanistan, but not to the extent that the choices and actions of individual actors can be overlooked or ignored. Further, the choices and actions of individual actors need not be explained in terms of ancient animosities or historic tendencies, but rather were calculated moves to secure power. In support of this argument, international, national, and individual level factors are examined. ii Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban by, Brandon Smith Approved by: _________________________, Advisor Karen L. Dawisha _________________________, Reader John M. Rothgeb, Jr. _________________________, Reader Homayun Sidky Accepted by: ________________________, Director, University Honors Program iii Thanks to Karen Dawisha for her guidance and willingness to help on her year off, and to John Rothgeb and Homayun Sidky for taking the time to read the final draft and offer their feedback. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

From the Editor

EDITORIAL STAFF From the Editor ELIZABETH SKINNER Editor Happy New Year, everyone. As I write this, we’re a few weeks into 2021 and there ELIZABETH ROBINSON Copy Editor are sparkles of hope here and there that this year may be an improvement over SALLY BAHO Copy Editor the seemingly endless disasters of the last one. Vaccines are finally being deployed against the coronavirus, although how fast and for whom remain big sticky questions. The United States seems to have survived a political crisis that brought EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD its system of democratic government to the edge of chaos. The endless conflicts VICTOR ASAL in Syria, Libya, Yemen, Iraq, and Afghanistan aren’t over by any means, but they have evolved—devolved?—once again into chronic civil agony instead of multi- University of Albany, SUNY national warfare. CHRISTOPHER C. HARMON 2021 is also the tenth anniversary of the Arab Spring, a moment when the world Marine Corps University held its breath while citizens of countries across North Africa and the Arab Middle East rose up against corrupt authoritarian governments in a bid to end TROELS HENNINGSEN chronic poverty, oppression, and inequality. However, despite the initial burst of Royal Danish Defence College change and hope that swept so many countries, we still see entrenched strong-arm rule, calcified political structures, and stagnant stratified economies. PETER MCCABE And where have all the terrorists gone? Not far, that’s for sure, even if the pan- Joint Special Operations University demic has kept many of them off the streets lately. Closed borders and city-wide curfews may have helped limit the operational scope of ISIS, Lashkar-e-Taiba, IAN RICE al-Qaeda, and the like for the time being, but we know the teeming refugee camps US Army (Ret.) of Syria are busy producing the next generation of violent ideological extremists. -

The Tribes of Pakistan: Finding Common Ground in Uncommon Places

The Tribes of Pakistan: Finding Common Ground in Uncommon Places By Paul G. Paterson, BSc. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In CONFLICT ANALYSIS AND MANAGEMENT We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ________________________________ Hrach Gregorian, PhD Faculty Supervisor ________________________________ Fred Oster, PhD Program Head, MACAM Program ________________________________ Alex Morrison, MSC, MA Director, School of Peace and Conflict Management ROYAL ROADS UNIVERSITY June 23, 2011 © Paul G. Paterson, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-76004-8 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-76004-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. -

The Evolution and Expansion of Eleventh Amendment Immunity: Legal Implications for Public Institutions of Higher Education Krista Michele Mooney

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 The Evolution and Expansion of Eleventh Amendment Immunity: Legal Implications for Public Institutions of Higher Education Krista Michele Mooney Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION THE EVOLUTION AND EXPANSION OF ELEVENTH AMENDMENT IMMUNITY: LEGAL IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION By KRISTA MICHELE MOONEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Semester Approved Fall Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Krista Michele Mooney All Rights Reserved The members of the committee approved the dissertation of Krista Michele Mooney defended on October 7, 2005. ______________________________ Joseph C. Beckham Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Michael J. Mondello Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Dale W. Lick Committee Member ______________________________ Robert A. Schwartz Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________________________________________________ Joseph C. Beckham, Interim Chair, Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For my mother and father: my sounding boards, my cheerleaders, my -

Sasha Paul Final Thesis

PAKISTAN AGAINST ITSELF: THE RISE OF EXTREMISM By Sasha J Paul Bachelor of Arts, Dalhousie University, 1997 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: David Charters, PhD, Department of History Examining Board: Gary Waite, PhD, Acting Director of Graduate Studies, Chair J. Marc Milner, PhD, Department of History Lawrence Wisniewski, PhD, Department of Sociology This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK April 2014 ©Sasha J Paul, 2014 ABSTRACT An analysis of Pakistan’s political, social, institutional and regional history reveals two principal problems facing the state: first, the enmity that developed between Pakistan and India following partition, has morphed into an overwhelming national obsession with India which has supported unbridled growth of Pakistan’s security institutions at the expense of Pakistan’s ability to govern its own people. Second, despite the lofty aims of Mohammad Ali Jinnah to build his country into a modern democratic and secular state, the confluence of certain key factors have prevented Pakistan from ever moving towards this ideal. This study will examine the complex web of factors that have spawned Pakistan’s current situation as a failing nuclear state such as: the outstanding grievances from the partition of colonial India and subsequent conflicts, support of the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan and the social, institutional, and economic domestic factors. Pakistan’s overt and tacit support of extremists is a double-edged sword that undermines at any semblance of stability for this country as it grapples with a growing number of suicide attacks, targeted killings, kidnappings, increased criminal activity and rising drug addiction, yet the status quo continues with little expectation of positive change. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Making Sense of Daesh in Afghanistan: a Social Movement Perspective

\ WORKING PAPER 6\ 2017 Making sense of Daesh in Afghanistan: A social movement perspective Katja Mielke \ BICC Nick Miszak \ TLO Joint publication by \ WORKING PAPER 6 \ 2017 MAKING SENSE OF DAESH IN AFGHANISTAN: A SOCIAL MOVEMENT PERSPECTIVE \ K. MIELKE & N. MISZAK SUMMARY So-called Islamic State (IS or Daesh) in Iraq and Syria is widely interpreted as a terrorist phenomenon. The proclamation in late January 2015 of a Wilayat Kho- rasan, which includes Afghanistan and Pakistan, as an IS branch is commonly interpreted as a manifestation of Daesh's global ambition to erect an Islamic caliphate. Its expansion implies hierarchical order, command structures and financial flows as well as a transnational mobility of fighters, arms and recruits between Syria and Iraq, on the one hand, and Afghanistan–Pakistan, on the other. In this Working Paper, we take a (new) social movement perspective to investigate the processes and underlying dynamics of Daesh’s emergence in different parts of the country. By employing social movement concepts, such as opportunity structures, coalition-building, resource mobilization and framing, we disentangle the different types of resource mobilization and long-term conflicts that have merged into the phenomenon of Daesh in Afghanistan. In dialogue with other approaches to terrorism studies as well as peace, civil war and security studies, our analysis focuses on relations and interactions among various actors in the Afghan-Pakistan region and their translocal networks. The insight builds on a ten-month fieldwork-based research project conducted in four regions—east, west, north-east and north Afghanistan—during 2016. We find that Daesh in Afghanistan is a context-specific phenomenon that manifests differently in the various regions across the country and is embedded in a long- term transformation of the religious, cultural and political landscape in the cross-border region of Afghanistan–Pakistan. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. BEYOND AL-QA’IDA: THE THEOLOGY, TRANSFORMATION AND GLOBAL GROWTH OF SALAFI RADICALISM SINCE 1979 By Jeffrey D. Leary Submitted to the Faculty of the School o f International Service O f American University In Partial Fulfillment o f The Requirements for the Degree of Master o f Arts In Comparative Regional Studies o f the Middle East CO' (jhp Louis W. -

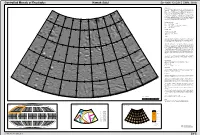

Hi-Resolution Map Sheet

Controlled Mosaic of Enceladus Hamah Sulci Se 400K 43.5/315 CMN, 2018 GENERAL NOTES 66° 360° West This map sheet is the 5th of a 15-quadrangle series covering the entire surface of Enceladus at a 66° nominal scale of 1: 400 000. This map series is the third version of the Enceladus atlas and 1 270° West supersedes the release from 2010 . The source of map data was the Cassini imaging experiment (Porco et al., 2004)2. Cassini-Huygens is a joint NASA/ESA/ASI mission to explore the Saturnian 350° system. The Cassini spacecraft is the first spacecraft studying the Saturnian system of rings and 280° moons from orbit; it entered Saturnian orbit on July 1st, 2004. The Cassini orbiter has 12 instruments. One of them is the Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem 340° (ISS), consisting of two framing cameras. The narrow angle camera is a reflecting telescope with 290° a focal length of 2000 mm and a field of view of 0.35 degrees. The wide angle camera is a refractor Samad with a focal length of 200 mm and a field of view of 3.5 degrees. Each camera is equipped with a 330° 300° large number of spectral filters which, taken together, span the electromagnetic spectrum from 0.2 60° 320° 310° to 1.1 micrometers. At the heart of each camera is a charged coupled device (CCD) detector 60° consisting of a 1024 square array of pixels, each 12 microns on a side. MAP SHEET DESIGNATION Peri-Banu Se Enceladus (Saturnian satellite) 400K Scale 1 : 400 000 43.5/315 Center point in degrees consisting of latitude/west longitude CMN Controlled Mosaic with Nomenclature Duban 2018 Year of publication IMAGE PROCESSING3 Julnar Ahmad - Radiometric correction of the images - Creation of a dense tie point network 50° - Multiple least-square bundle adjustments 50° - Ortho-image mosaicking Yunan CONTROL For the Cassini mission, spacecraft position and camera pointing data are available in the form of SPICE kernels. -

Pakistan-Christians-Converts.V4.0

Country Policy and Information Note Pakistan: Christians and Christian converts Version 4.0 February 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.