A1 BIBER Rosary Sonatas • Daniel Sepec (Vn); Hille Perl (Vdg); Lee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andreas Ottensamer: Der Seelenbohrer Schätze Für Die Nackte Den Plattenschrank 57 Gulasch-Kanone 22 Boulevard: Tianwa Yang: Bunte Klassik 58 25.07

Das Klassik & Jazz Magazin 2/2015 HILLE PERL Unter Strom Bryan Hymel und Piotr Beczała: Zeit für Helden Frank Peter Zimmermann: Feilen am perfekten Klang François Leleux: Seelenbohrer Pierre Boulez: Maître der Moderne Immer samstags aktuell www.rondomagazin.de Foto: Rankin Foto: Foto: Shervin Lainez Foto: 7. bis 16. maiSchirmherr: Oberbürgermeister 2015 Jürgen Nimptsch Nigel Kennedy Lizz Wright Foto: Ferrigato Foto: Foto: Stephen Freiheit Stephen Foto: onn www.jazzfest-bonn.de zfest Marilyn Mazur Wolfgang Muthspiel b Karten an allen Do 7.5. Post Tower Mo 11.5. Brotfabrik VVK-Stellen Pat Martino Trio Peter Evans – Zebulon Trio z und unter www.bonnticket.de Ulita Knaus Hanno Busch Trio Fr 8.5. LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn Di 12.5. Haus der Geschichte Anke Helfrich Trio Wolfgang Muthspiel Trio Norbert Gottschalk Quintett Efrat Alony Trio Sa 9.5. Universität Bonn Mi 13.5. Bundeskunsthalle ja Lizz Wright Marilyn Mazur‘s Celestial Circle Stefan Schultze – Large Ensemble Frederik Köster – Die Verwandlung So 10.5. Volksbank-Haus Do 14.5. Beethoven-Haus Bonn Michael Schiefel & David Friedman Enrico Rava meets Michael Heupel Gianluca Petrella & Giovanni Guidi Julia Kadel Trio Fr 15.5. Bundeskunsthalle Franco Ambrosetti Sextet feat. Terri Lyne Carrington, Greg Osby, Buster Williams WDR Big Band & Erik Truffaz Sa 16.5. Telekom Forum Nigel Kennedy plays Jimi Hendrix Rebecca Treschers Ensemble 11 Fotos: Johannes Gontarski; Dario Acosta/Warner Classics; Georg Thum/Sony; Lars Borges/Mercury Calssics; Friedrun Reinhold Calssics; Friedrun Borges/Mercury Dario Thum/Sony; Acosta/Warner Lars Johannes Gontarski; Classics; Georg Fotos: 2 Rondo.indd 1 09.02.15 15:26 Lust auf Themen Musikstadt: St. -

Konzert Programm 2020−21 Schinkelsaal & Gartensaal Im Gesellschaftshaus Am Klosterbergegarten Allgemeines Allgemeines

GESELLSCHAFTSHAUS-MAGDEBURG.DE KONZERT PROGRAMM 2020−21 SCHINKELSAAL & GARTENSAAL IM GESELLSCHAFTSHAUS AM KLOSTERBERGEGARTEN ALLGEMEINES ALLGEMEINES KLAVIERMUSIK Editorial 2 IM SCHINKEL- UND GARTENSAAL Sa 19.09.20 FiktionundAbstraktion 27 Sa23.01.21Roots 28 KAMMERMUSIK Sa24.04.21 Solorezital 30 IM SCHINKEL- UND GARTENSAAL Sa12.06.21 Musikbewegt 30 Sa 12.09.20 JosephJoachimundClaraSchumann 4 Sa 17.10.20 AusderNeuenWelt 7 Sa14.11.20AgeofPassion 8 MUSIK AM NACHMITTAG Sa 09.01.21 CircusundRegen 9 IM GARTENSAAL Sa27.02.21 Klangrausch 11 So 01.11.20 RosyundUrsula–DieÜberlebenden 32 Sa20.03.21 ClairdeLune 13 So 17.01.21 Neujahrskonzert 33 Sa 10.04.21 Quartetconcertant 14 So 28.03.21 Frangis–DieSeidenweberin 36 Sa 29.05.21 DieWahrheitunddasLeben 16 So 09.05.21 Liana–DieKosmopolitin 38 SONNTAGSMUSIK FÜR JUNGE HÖRER IM SCHINKELSAAL IM GESELLSCHAFTSHAUS So06.09.20 570.Zuviert… 18 So 27.09.20 FrauGerburgverkauftdenJazz 39 So 04.10.20 571.QuerdurchEuropa 19 Mi 21.10.20 KarnevalderTiere 40 So01.11.20 572.Zudritt… 20 Mi 10.02.21 DieBremerStadtmusikanten 41 So 06.12.20 573.ZuAdventundWeihnachten 21 Mi31.03.21 DerfalscheTon 42 So 03.01.21 574.Zuzweit… 21 So 18.04.21 TrioMeetsVoice 43 So 07.02.21 575.Ausgezeichnet! 22 Mi19.05.21Amadeus 44 So 07.03.21 576.Seigetreu…! 23 So 11.04.21 577.GambeundFagott 24 VERANSTALTUNGSKALENDER 45 KARTENSERVICE 56 ABONNEMENTBEDINGUNGEN 58 PREISE 59 IMPRESSUM 60 1 1 ALLGEMEINESEDITORIAL ALLGEMEINESEDITORIAL Liebe Musikfreunde, zwei Jubiläen können in der neuen Konzertsaison in unserem Haus Spieler dieses wundervollen Instruments werden sich im Gesell- gefeiert werden! Am 14. Oktober 2005 wurde das Gesellschaftshaus schaftshaus die „Klinke in die Hand geben“ – so u.a. -

Masterclasses 2021 Will Select the Number of Participants in the Masterclasses Will Be Around 15 Participants Who Will Form the European Limited to 7 Per Class

European Hanseatic Ensemble Application Theteachersofthemasterclasses2021willselect The number of participants in the masterclasses will be around 15 participants who will form the European limited to 7 per class. In the event that there are more Hanseatic Ensemble and will tour hanseatic cities in applicants than available places, selection will be determined thesummerof2022undertheartisticdirectionof upon evaluation of the provided audio material. Manfred Cordes. For those who will participate in the Application deadline: April 30th 2021 concerts, the course fee will be refunded and a daily INTERNATIONAL rate will be payed for rehearsal and concert days. The online application form and information about Resulting travel and accommodation expenses will transfer of the audio files (not exceeding 15 minutes in MASTERCLASSES be covered as well. total) is available on our website www.hanseatic-ensemble.eu/en/masterclasses 2021 Thespecificconcertprogrammefor2022willbe adapted to the structure of the ensemble, thus will All applicants will be informed about possible Soloandensemblemusicaround1600 be developed after the selection of the ensemble participationbyJune15th2021atthelatest.Ifyouare members. The goal is a balanced distribution of selected, we kindly request that you pay the course fee of September 20th - 23rd 2021 singers, string, wind and continuo players which will 150€byJuly15th2021. allow for the performance of multi-choral works. in Lübeck We have booked budget accommodation for you in Lübeck (DJH Youth hostel), however costs for travel, Ulrike Hofbauer · Voice accommodation (youth hostel, hotel, etc.) and meals are Jan Van Elsacker · Voice to be absorbed by the participants. -

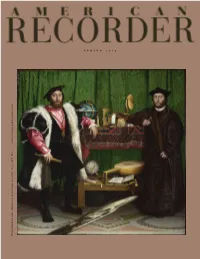

S P R I N G 2 0

Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. LIV, No. 1 • www.americanrecorder.org spring 2013 SOPRANINO TO SUBBA SS A WELL-TUNED CON S ORT www.moeck.com Anzeige_Orgel_A4.indd 1 11.11.2008 19:21:44 Uhr Lost in Time Press New works and arrangements for recorder ensemble Compositions by Frances Blaker Paul Ashford Hendrik de Regt and others Inquiries: Corlu Collier PMB 309 2226 N Coast Hwy Newport, Oregon 97365 www.lostintimepress.com [email protected] Dream-Edition – for the demands of a soloist Enjoy the recorder Mollenhauer & Adriana Breukink Enjoy the recorder Dream Recorders for the demands of a soloist New: due to their characteristic wide bore and full round sound Dream-Edition recorders are also suitable for demanding solo recorder repertoire. These hand-finished instru- ments in European plumwood with maple decorative rings combine a colourful rich sound with a stable tone. Baroque fingering and double holes provide surprising agility. TE-4118 Tenor recorder with ergonomic- ally designed keys: • Attractive shell-shaped keys • Robust mechanism • Fingering changes made TE-4318 easy by a roll mechanism fitted to double keys • Well-balanced sound a1 = 442 Hz Soprano and alto in luxurious leather bag, tenor in a hard case TE-4428 www.mollenhauer.com Soprano Alto Tenor (with double key) TE-4118 Plumwood with maple TE-4318 Plumwood with maple TE-4428 Plumwood with maple decorative rings decorative rings decorative rings Editor’s ______Note ______ ______ ______ ______ Volume LIV, Number 1 Spring 2013 efore you ask: yes, that’s a skull on the Features cover of this issue. -

Heinric H Sc H

HeinricH scHütz The Complete Narrative Works Ars nova copenhagen, Paul Hillier HeinricH scHütz (1585-1672) CD 1 Lukas-Passion SWV 480 (1666) �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �52:41 The Complete Narrative Works Historia des Leidens und Sterbens unsers Herrn und Heilandes Jesu Christi nach dem Evangelisten St. Lukas Ars nova copenhagen, Paul Hillier 1 Eingang 1:34 2 Evangelist: Es war aber nahe das Fest der süßen Brot 14:03 3 Evangelist: Und er ging hinaus nach seiner Gewohnheit 9:17 4 Evangelist: Die Männer aber, die da Jesum hielten 3:19 5 Evangelist: Und der ganze Haufe stund ab ����������������������������������������������������������������������������7:19 6 Evangelist: Aber sie lagen ihm an mit großen Geschrei 11:09 7 Evangelist: Da aber der Hauptmann sahe ������������������������������������������������������������������������������3:54 8 Beschluß 2:07 Johan Linderoth, evangelist Jakob Bloch Jespersen, Jesus CD 2 Weihnachtshistorie SWV 435 (c� 1660) �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �34:43 1 Eingang 1:18 2 Evangelist 2:57 3 Intermedium 1 Der Engel zu den Hirten -

Hille Perl & Friends

Hille Perl & Friends Ballads within a dream Von Elfen- und Eselsträumen - mit Clare Wilkinson (Sopran), Veronika Skuplik (Violin), Hlile Perl (Gambe) und Andreas Arend (Laute) Englische Folksongs und Balladen treffen auf Lieder von Henry Purcell, Lautenlieder und solistische Improvisationen für Theorbe und virtuose Streichermusik von den britischen Inseln. …eine Sommernacht könnte der Hintergrund sein, vielleicht ja eine Mittsommernacht! Programmfolge A Love Song -- John Blow Passamezzo Antico - Su Saltarello -- Improvisation for theorbo on the traditional theme Out of this wood -- Traditional melody, text by William Shakespeare Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Basso continuo -- Henry Eccles L´amour de moy -- Traditional, Arranged by Jean Richafort Passamezzo Moderno - Su Saltarello -- Improvisation for theorbo on the traditional theme Have you seen the white lily grow? -- attributed to Robert Johnson ' Twas within a furlong of Edinborough town -- Henry Purcell Black is the colour of my true love´s hair -- Traditional Ground in E Minor for Bass Viol and Basso Continuo -- Christopher Simpson Sonata in A Major for Violin, Viola da Gamba and Basso continuo -- Godfrey Finger I will give my love an apple -- Traditional Music for a while -- Henry Purcell Drink to me only with thine eyes-- Anonymous melody, text by Ben Jonson Rest, sweet nymphs-- Francis Pilkington Greensleeves-- Traditional - Die CD ist nominiert für einen OPUS Klassik - erika esslinger konzertagentur, Werfmershalde 13, 70190 Stuttgart Fon +49 (0)711 722 3440, Fax: +49 (0)711 722 34411, [email protected], www.konzertagentur.de Hille Perl & Friends Die vier Elemente Ein Mutter- Tochter Projekt Feuer Marthe Perl Präludium Irish Folk Flag of Fire Fire in the Mountain Hag by the Fire Antonio Soler Fandango Wasser Marthe Perl Präludium Tobias Hume Captain Hume's Lamentations Richard Lachrimae Sumarte John Gillard to Lachrimae Downland Monsieur de La Vignon Sainte Colombe *** Luft Marthe Perl Präludium Marin Marais Bourrasque Le Jeu du Volant Musette Anon. -

Allmusic Review by James Manheim

A2 AllMusic Review by James Manheim [-] Hille Perl and Lee Santana, a German viola da gamba player and an American theorbo player from Florida, met in Bremen's train station in 1984 and formed what they call a professional and personal "work in progress." Here they offer a disc of music by Marin Marais, a renowned French viol virtuoso and court musician of the late seventeenth century. What fame he has among general listeners comes from his appearance as a character in the 1991 film Tous les matins du monde, which in music-mad Germany caused passers-by, Perl says, to stop asking her "hey, is that a guitar?" and start asking "is that a six- or a seven-string?" In the U.S., music for viol and theorbo qualifies as an out-of-the-way corner of the musical universe, and Perl and Santana make things still more obscure with a lengthy liner-note justification for performing the music on this particular pair of instruments. (It involves the discovery of a Scottish manuscript that did not specify the bass instrumentation that appeared in later Marais publications.) Nevertheless, it's all somehow quite compelling. Perl is an exceptionally smooth player, and she executes the dances of these French suites with the lightness they deserve. In performing the variation sets that Marais would have used to display his own virtuosity, she's got power in reserve. And the music throughout has that elusive meshing of mutually familiar personalities that is the mark of effective chamber music. Marin Marais: Pour la Violle et le Théorbe, in short, comes off as something personal -- an impression intensified by the elegant dedication, written in the old- fashioned style of the French court, of the music to the public by the performers. -

6 FLUTE SONATAS BWV 1030 - 1035 and Viola Da Gamba 16 Allegro

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685 - 1731) Sonatas for recorder, harpsichord and viola da gamba BWV 1030 - 1035 Michala Petri recorder · Hille Perl viola da gamba · Mahan Esfahani harpsichord Sonata B minor BWV 1030 Sonata C major BWV 1033 for alto recorder, concertato harpsichord and for tenor recorder and basso continuo viola da gamba 11 Allegro – Presto ............................1.35 1 Andante ........................................7.42 12 Allegro ...........................................2.17 2 Largo e dolce ................................3.25 13 Adagio ..........................................1.38 3 Presto ...........................................1.31 14 Menuetto 1 + 2 .............................2.54 JOHANN SEBASTIAN 4 Allegro ...........................................4.06 Sonata G minor BWV 1034 for alto recorder Sonata E flat major BWV 1031 and basso continuo (original key E minor) BACH for tenor recorder, concertato harpsichord 15 Adagio ma non tanto ....................2.59 6 FLUTE SONATAS BWV 1030 - 1035 and viola da gamba 16 Allegro ...........................................2.35 Michala Petri recorder · Hille Perl viola da gamba 5 Allegro moderato ..........................3.24 17 Andante ........................................4.20 harpsichord 6 Siciliano ........................................2.31 18 Allegro ...........................................4.38 Mahan Esfahani 7 Allegro ...........................................4.18 Sonata F major BWV 1035 for alto recorder Sonata G major BWV 1032 and basso continuo (original -

1998 Mar-Apr

Boston Classical Guitar Society http://home.att.net/~glorv/BCGS.html Volume 5, Number 4 newsletterMarch/April ‘98 Letter to Members Mark Your Calendars and Get Dear Members, Ready for Spring 1998! CONCERTS With a combined sense of sadness and relief, Sunday, April 5, 3:00 p.m. I will be relinquishing the title of artistic BCGS sponsors The Virtual Consortat the First Church, Uni-tarian director at the end of the 97-98 season. When Universalist, Jamaica Plain. See page 2 for biographical profiles I assumed the role three seasons ago, it was and the insert page Flyer for full details on this concert. with some trepidation. But I also had a strong desire to sustain the momentum the society gained under the Sunday, May 3, 4:00 p.m. leadership of Berit Strong. It’s been an honor to hold this posi- BCGS and MIT co-sponsor Jad Azkoul at MIT’s Killian Hall, Cambridge. See page 3 for Jad Azkoul’s biography. tion, and I hope that I have lived up to the expectations of the members. Saturday, June 6, 7:30 p.m. BCGS sponsors Duo LiveOak at the Friends Meetinghouse, 5 There are a few accomplishments that I would like to be Longfellow Park, Cambridge. More information on this event will remembered for. Badi Assad’s concert had the biggest audience be available in the next newsletter. of any BCGS event that I am aware of. Our first significant ALSO OF NOTE effort to apply for funds from both public and private grant Saturday, March 28, 1:30 p.m. -

G0100030966215 Elements Fire Earth Water Air (A Mother-Daughter-Project)

G0100030966215 Elements fire earth water air (a mother-daughter-project) 1 Prelude Feuer ---1.04 Marthe Perl (*1983) 14 Prelude Luft ---1.59 Marthe Perl 2 Flag of Fire ---3.26 Irish Folk (arr. Hille Perl (*1965)) 15 Bourrasque ---1.04 Marin Marais 3 Fire in the Mountain ---1.24 Irish Folk (arr. Hille Perl) 16 Change of Ayre ---2.51 Thomas Ford (1580–1648) 4 Hag by the Fire ---2.24 Irish Folk (arr. Hille Perl) 17 Baggepipes ---1.22 Thomas Ford 5 Fandango ---12.49 Padre Antonio Soler (1729–1783) 18 Wild Goose Chase ---1.20 Thomas Ford (arr. Hille Perl/Marthe Perl) 19 Le Jeu du Volant ---1.50 Marin Marais 20 Andante 2.41 Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) 6 Prelude Erde ---1.29 Marthe Perl --- 7 An Old Bog Ground ---0.46 Irish Folk (arr. Hille Perl) 8 Faronell‘s Division upon a Ground ---5.45 Michel Farinel (1649–1726) 9 Tombeau pour Mr Meliton ---8.55 Marin Marais (1656–1728) Hille Perl Viola da gamba 10 Prelude Wasser ---1.12 Marthe Perl Matthias Alban, Bozen 1686 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 19, 20) 11 Captain Humes Lamentations ---9.29 Tobias Hume (1569–1645) Claus Derenbach, Köln 1998 (13, 16, 17, 18) 12 Lachrimae Pavane ---6.17 Richard Sumarte (15??–nach 1630) 13 Galliard to Lachrimae ---3.23 John Dowland (1563–1626) Marthe Perl (arr. Marthe Perl) Viola da gamba & treble viol viola da gamba, Claus Derenbach, Köln 2003 (1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15,19, 20) viola da gamba, Claus Derenbach, Köln 2007 (11, 12, 13, 16, 17, 18) treble viol, François Danger, Rouen 2003 (3, 4, 7) 2 3 Hille’s Special Thanks go out to Ruth Hundsdörfer for editorial advice and to Edzard Wagenaar for conceptual counselling, to Peter Laenger as always for creative recording, to the team at Sony for their support and trust, to Lee Santana for his presence and inspiration. -

Tokenism in the Representation of Women Composers on BBC Radio 3

The Other Composer: Tokenism in the Representation of Women Composers on BBC Radio 3 Valerie Abma (5690323) Deadline: 15 juni, 2018 Begeleider: dr. Ruxandra Marinescu BA Eindwerkstuk Muziekwetenschap Universiteit Utrecht MU3V14004 2017-2018 Blok 4 Table of Contents Abstract.…………………………………….………………………………………………… 3 Introduction: The Other Composer.…………………...……………………………………… 4 Chapter 1: The Negligible Impact.……………………………….…………………………… 7 Chapter 2: BBC Radio 3 and its aims.………………………………………………………. 11 Chapter 3: BBC Radio 3 and its tokenism………………………………….…..…………….14 3.1: The BBC guidelines for diversity……………………………….……………….14 3.2: Programming…………………………………………………………………… 15 3.3: “Mind your language”.…………………….…………………………………… 17 Conclusion.…………………………………………………..……………………………… 20 Bibliography.…………………………………………………...…………………………… 22 BBC Website Data.……………………..…………………………………………… 25 Appendix 1.…………………………………………………………………………..……… 27 Appendix 2.…………………………………………..……………………………………… 31 Appendix 3.…………………………………………..……………………………………… 39 Appendix 4.…………………………………………...………………………………………44 2 Abstract This thesis focuses on the tokenism, which, as I will demonstrate, is present in the representation of women composers on BBC Radio 3. More specifically, this thesis looks at how tokenism hinders the equality in the representation of men and women composers. The presence of tokenism will be illustrated by data of BBC Radio 3 from 2015 until 2018. As long as compositions by women composers are programmed as tokens, and therefore only as a gesture of temporary change within a dedicated space -

23 October 2020

23 October 2020 12:01 AM Frederick Delius (1862-1934) On hearing the first cuckoo in spring for orchestra (RT.6.19) (1911/12) Symphony Nova Scotia, Georg Tintner (conductor) CACBC 12:09 AM Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli (1630-1670) Sonata in E minor Op.4`1 (La Bernabea) for violin and continuo Daniel Sepec (violin), Hille Perl (viola da gamba), Lee Santana (theorbo), Michael Behringer (harpsichord) PLPR 12:15 AM Henry Purcell (1659-1695) Let mine eyes run down with tears, Z.24 Grace Davidson (soprano), Aleksandra Lewandowska (soprano), Damien Guillon (counter tenor), Samuel Boden (tenor), Matthew Brook (bass), Collegium Vocale Ghent, Philippe Herreweghe (director) PLPR 12:24 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Robert Levin (arranger) Larghetto and Allegro in E flat, KV deest Soós-Haag Piano Duo (piano duo) CHSRF 12:36 AM Bernhard Henrik Crusell (1775-1838) Concertino for bassoon and orchestra in B flat major Juhani Tapaninen (bassoon), Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jukka-Pekka Saraste (conductor) FIYLE 12:56 AM Gabriel Faure (1845-1924) Violin Sonata no 1 in A major Op 13 Elena Urioste (violin), Michael Brown (piano) GBBBC 01:19 AM Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Don Carlos Act III, Scene II: Rodrigo, Marquis of Posa's aria 'Per me giunto' Gaetan Laperriere (baritone), Orchestre Symphonique de Trois Rivieres, Gilles Bellemare (conductor) CACBC 01:30 AM Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Romeo and Juliet (fantasy overture, 1880 version) ORF Radio Symphony Orchestra, Pinchas Steinberg (conductor) ATORF 01:50 AM Johann Wenzel Kalliwoda