Heinric H Sc H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coro Casa Da Música, Paul Hillier (N.1949)

27 Set 2015 Coro 18:00 Sala Suggia - Casa da Música TRANSGRESSÕES Paul Hillier direcção musical Inglaterra Interlúdio Henry Purcell (1659 -1695) Steve Reich / Paul Hillier (1949) I was glad when they said unto me Clapping Music (arranjo vocal) John Blow (1649 -1708) Salvator mundi Inglaterra Purcell/Sven -David Sandström (1942) John Dowland (1563 -1626) Hear my prayer / Paul Hillier Lacrimae 1 a 3 Interlúdio Henry Bishop (1786 -1855) Steve Reich (1936) Who is Silvia Clapping Music John Dowland / Paul Hillier Lacrimae 4 e 5 América Thomas Morley (1557/8 -1602) Justin Morgan (1747 -1798) Sweet nymph come to thy lover Montgomery Robert Lucas de Pearsall (1795 -1856) Abraham Wood (1752 -1804) Sing we and chaunt it Brevity John Dowland / Paul Hillier Justin Morgan Lacrimae 6 e 7 Amanda William Billings (1746 -1800) Jargon Duração aproximada: 1 hora sem intervalo Elisha West (1756 -1832) Tradução dos textos originais nas páginas 7 a 11 Evening Hymn A CASA DA MÚSICA É MEMBRO DE O conceito de originalidade é, indubitavel‑ compositores explorar e patentear as suas mente, um dos valores mais propalados próprias capacidades e, em simultâneo, no paradigma artístico contemporâneo. homenagear os autores dos seus modelos. Associada de um modo umbilical a uma ima‑ Já durante o período Barroco, por motivos gem idealizada de qualquer processo de que o musicólogo J. Peter Burkholder associa natureza criativa – fazendo ‑o depender de ao carácter funcional da música coeva, esta um momento de inspiração ou de um rasgo de acabava, muitas vezes, por ser executada e genialidade –, a emergência deste conceito escutada exclusivamente na ocasião para a é, no entanto, relativamente recente. -

Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from JS Bach's

Messiahs and Pariahs: Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) to David Lang’s the little match girl passion (2007) Johann Jacob Van Niekerk A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Giselle Wyers, Chair Geoffrey Boers Shannon Dudley Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2014 Johann Jacob Van Niekerk University of Washington Abstract Messiahs and Pariahs: Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) to David Lang’s the little match girl passion (2007) Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Giselle Wyers Associate Professor of Choral Music and Voice The themes of suffering and social conscience permeate the history of the sung passion genre: composers have strived for centuries to depict Christ’s suffering and the injustice of his final days. During the past eighty years, the definition of the genre has expanded to include secular protagonists, veiled and not-so-veiled socio- political commentary and increased discussion of suffering and social conscience as socially relevant themes. This dissertation primarily investigates David Lang’s Pulitzer award winning the little match girl passion, premiered in 2007. David Lang’s setting of Danish author and poet Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl” interspersed with text from the chorales of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) has since been performed by several ensembles in the United States and abroad, where it has evoked emotionally visceral reactions from audiences and critics alike. -

University Musical Society the Milliard Ensemble

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY THE MILLIARD ENSEMBLE David James, Countertenor John Potter, Tenor Rogers Covey-Crump, Tenor Gordon Jones, Baritone Tuesday Evening, March 5, 1991, at 8:00 Rackham Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan Sound Patterns Tu civium primas ......................... Anonymous (c. 14th century) Alma polls religio - Axe poli cum artica ............... Anorrymous (c. 14th century) Reginarum dominam ....................... .Anonymous (c. 1170) Summa ............................. Arvo Part (b. 1935) Verbum bonum et suave ..................... .Anonymous (c. 1170) Musicalis sciencia Sciencie laudabili ................. Anonymous (c. 14th century) Glorious Hill .......................... Gavin Bryars (b. 1943) INTERMISSION Miraculous love's wounding .................. .Thomas Morley (1557-1602) Thomas gemma Cantuarie .................... .Anorrymous (14th century) In nets of golden wyers ..................... Thomas Morley (1557-1602) Tu solus qui facis mirabilia ................... Josquin Desprez (c. 1440-1521) Litany for the Whale ........................ John Cage (b. 1912) Prest est mon mal ..................... Cornelius Verdonck (1563-1625) Joy, mirth, triumphs ...................... Henry Purcell (1659-1695) Gloria from Messe de Nostre Dame ............. Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300-1377) The Milliard Ensemble appears by arrangement with Beverly Simmons, Artist Representative, Cleveland, Ohio. The Hillard Ensemble records for ECM, EMI, and Harmonia Mundi France. Copies of this title page are available in larger print; -

Ars Nova Copenhagen - Ltg

Ars Nova Copenhagen - Ltg. Paul Hillier Baltic Voices Vokalmusik aus dem Ostseeraum vom Mittelalter bis in die Gegenwart Die Piae Cantiones sind eine gedruckte Sammlung von Schulliedern aus Schweden und Finnland, wo ihr Gebrauch weit verbreitet war. Gedruckt wurde die Sammlung 1582 in Greifswald, wo es zu dieser Zeit schon Notendrucker gab. Gleichzeitig ist dies ein "Zeugnis für die kulturelle Zusammengehörigkeit des Ostseeraums" (Folke Bohlin). Ars Nova Copenhagen kombiniert diese selten zu hörenden Lieder mit weiteren musikalischen Zeugnissen aus dem Ostseeraum, vor allem aus der heutigen Zeit. Piæ Cantiones (1582) Ave Maris stella Personent hodie Paranymphus Gaudete Christus est natus Letetur Jerusalem Arvo Pärt | Estland Auswahl jüngerer Werke Santa Ratniece | Lettland Horo Horo Hata Hata Rytis Mazulis | Litauen The dazzled eye lost its speech Heinrich Schütz | Deutschland aus der Geistlichen Chormusik, 1648 Henryk Gorecki | Polen Totus tuus Piæ Cantiones Tempus ad est floridum Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen | Dänemark Igen erika esslinger konzertagentur, Werfmershalde 13, 70190 Stuttgart Fon +49 (0)711 722 3440, Fax: +49 (0)711 722 34411, [email protected], www.konzertagentur.de Ars Nova Copenhagen - Ltg. Paul Hillier Old World - New World Spanische Renaissance-Motetten, amerikanische Psalmvertonungen aus dem 18. Jahrhundert und zeitgenössische Werke Alte und Neue Musik zu kombinieren, war schon immer ein Markenzeichen von Ars Nova. In diesem Programm wird Alt und Neu gleich in zwei Richtungen in Verbindung gesetzt, nämlich zeitlich wie geographisch. Paul Hilliers langjährige enge Beziehung zu Arvo Pärt spiegelt sich in der Einbeziehung eines ganz neuen Stückes wider, das für Ars Nova 2017 geschrieben wurde. Arvo Pärt Kleine Litanei Alonso Lobo Ave Maria Arvo Pärt Virgencita Manuel de Sumaya La Bella Incorrupta * Elisha West Evening Hymn Christian Wolff Evening Shade, Wade Up Trad. -

Andreas Ottensamer: Der Seelenbohrer Schätze Für Die Nackte Den Plattenschrank 57 Gulasch-Kanone 22 Boulevard: Tianwa Yang: Bunte Klassik 58 25.07

Das Klassik & Jazz Magazin 2/2015 HILLE PERL Unter Strom Bryan Hymel und Piotr Beczała: Zeit für Helden Frank Peter Zimmermann: Feilen am perfekten Klang François Leleux: Seelenbohrer Pierre Boulez: Maître der Moderne Immer samstags aktuell www.rondomagazin.de Foto: Rankin Foto: Foto: Shervin Lainez Foto: 7. bis 16. maiSchirmherr: Oberbürgermeister 2015 Jürgen Nimptsch Nigel Kennedy Lizz Wright Foto: Ferrigato Foto: Foto: Stephen Freiheit Stephen Foto: onn www.jazzfest-bonn.de zfest Marilyn Mazur Wolfgang Muthspiel b Karten an allen Do 7.5. Post Tower Mo 11.5. Brotfabrik VVK-Stellen Pat Martino Trio Peter Evans – Zebulon Trio z und unter www.bonnticket.de Ulita Knaus Hanno Busch Trio Fr 8.5. LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn Di 12.5. Haus der Geschichte Anke Helfrich Trio Wolfgang Muthspiel Trio Norbert Gottschalk Quintett Efrat Alony Trio Sa 9.5. Universität Bonn Mi 13.5. Bundeskunsthalle ja Lizz Wright Marilyn Mazur‘s Celestial Circle Stefan Schultze – Large Ensemble Frederik Köster – Die Verwandlung So 10.5. Volksbank-Haus Do 14.5. Beethoven-Haus Bonn Michael Schiefel & David Friedman Enrico Rava meets Michael Heupel Gianluca Petrella & Giovanni Guidi Julia Kadel Trio Fr 15.5. Bundeskunsthalle Franco Ambrosetti Sextet feat. Terri Lyne Carrington, Greg Osby, Buster Williams WDR Big Band & Erik Truffaz Sa 16.5. Telekom Forum Nigel Kennedy plays Jimi Hendrix Rebecca Treschers Ensemble 11 Fotos: Johannes Gontarski; Dario Acosta/Warner Classics; Georg Thum/Sony; Lars Borges/Mercury Calssics; Friedrun Reinhold Calssics; Friedrun Borges/Mercury Dario Thum/Sony; Acosta/Warner Lars Johannes Gontarski; Classics; Georg Fotos: 2 Rondo.indd 1 09.02.15 15:26 Lust auf Themen Musikstadt: St. -

Konzert Programm 2020−21 Schinkelsaal & Gartensaal Im Gesellschaftshaus Am Klosterbergegarten Allgemeines Allgemeines

GESELLSCHAFTSHAUS-MAGDEBURG.DE KONZERT PROGRAMM 2020−21 SCHINKELSAAL & GARTENSAAL IM GESELLSCHAFTSHAUS AM KLOSTERBERGEGARTEN ALLGEMEINES ALLGEMEINES KLAVIERMUSIK Editorial 2 IM SCHINKEL- UND GARTENSAAL Sa 19.09.20 FiktionundAbstraktion 27 Sa23.01.21Roots 28 KAMMERMUSIK Sa24.04.21 Solorezital 30 IM SCHINKEL- UND GARTENSAAL Sa12.06.21 Musikbewegt 30 Sa 12.09.20 JosephJoachimundClaraSchumann 4 Sa 17.10.20 AusderNeuenWelt 7 Sa14.11.20AgeofPassion 8 MUSIK AM NACHMITTAG Sa 09.01.21 CircusundRegen 9 IM GARTENSAAL Sa27.02.21 Klangrausch 11 So 01.11.20 RosyundUrsula–DieÜberlebenden 32 Sa20.03.21 ClairdeLune 13 So 17.01.21 Neujahrskonzert 33 Sa 10.04.21 Quartetconcertant 14 So 28.03.21 Frangis–DieSeidenweberin 36 Sa 29.05.21 DieWahrheitunddasLeben 16 So 09.05.21 Liana–DieKosmopolitin 38 SONNTAGSMUSIK FÜR JUNGE HÖRER IM SCHINKELSAAL IM GESELLSCHAFTSHAUS So06.09.20 570.Zuviert… 18 So 27.09.20 FrauGerburgverkauftdenJazz 39 So 04.10.20 571.QuerdurchEuropa 19 Mi 21.10.20 KarnevalderTiere 40 So01.11.20 572.Zudritt… 20 Mi 10.02.21 DieBremerStadtmusikanten 41 So 06.12.20 573.ZuAdventundWeihnachten 21 Mi31.03.21 DerfalscheTon 42 So 03.01.21 574.Zuzweit… 21 So 18.04.21 TrioMeetsVoice 43 So 07.02.21 575.Ausgezeichnet! 22 Mi19.05.21Amadeus 44 So 07.03.21 576.Seigetreu…! 23 So 11.04.21 577.GambeundFagott 24 VERANSTALTUNGSKALENDER 45 KARTENSERVICE 56 ABONNEMENTBEDINGUNGEN 58 PREISE 59 IMPRESSUM 60 1 1 ALLGEMEINESEDITORIAL ALLGEMEINESEDITORIAL Liebe Musikfreunde, zwei Jubiläen können in der neuen Konzertsaison in unserem Haus Spieler dieses wundervollen Instruments werden sich im Gesell- gefeiert werden! Am 14. Oktober 2005 wurde das Gesellschaftshaus schaftshaus die „Klinke in die Hand geben“ – so u.a. -

Arvo Pärt Da Pacem

ARVO PÄRT DA PACEM ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Cover: Ash Tree by Sebastian Spreng (b. 1956) © 2005 Photo of EPCC: Tarvo Hanno Varres All texts and translations © harmonia mundi usa except as noted. Publisher: Universal Edition, A.G., Vienna, and Universal Edition Inc., New York. Nigulistekirik Organ by Rieger-Klosa, 1981. 4 manuals (including a Vox Humana register heard in “Salve Regina” at 3:18) and Pedal. Tracks 1 & 5: Recorded January 2006, Nigulistekirik, Tallinn, Estonia Tracks 2–4, 6, 8 & 9: Recorded September 2005, Nigulistekirik, Tallinn, Estonia Track 7: PAUL HILLIER Recorded October 2004, Tallinn Methodist Church, Estonia Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir with Christopher Bowers-Broadbent organ 2005, 2006 harmonia mundi usa 1117 Chestnut Street, Burbank, California 91506 Executive Producer: Robina G. Young Sessions Producers: Robina G. Young & Brad Michel Balance Engineer & Editor: Brad Michel DSD Engineer: Chris Barrett Recorded, edited & mastered in DSD 1 ARVO PÄRT / DA PACEM / Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir / Paul Hillier HMU 807401 © harmonia mundi ARVO PÄRT (b. 1935) 1 Da pacem Domine (2004) 5:45 2 Salve Regina (2001/2) 12:51 Zwei slawische Psalmen (1984 / 1997) 7:53 3 Psalm 117 3:47 4 Psalm 131 4:06 5 Magnificat (1989) 7:13 • Kaia Urb soprano 6 An den Wassern zu Babel (1976 / 1984 / 1991) 7:14 • Kaia Urb soprano • Tiit Kogerman tenor • Aarne Talvik bass 7 Dopo la vittoria (1996 / 1998) 11:11 8 Nunc dimittis (2001) 6:56 • Kaia Urb soprano 9 Littlemore Tractus (2000) 5:27 ESTONIAN PHILHARMONIC CHAMBER CHOIR Christopher Bowers-Broadbent organ (2, 6, 9) PAUL HILLIER 2 ARVO PÄRT / DA PACEM / Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir / Paul Hillier HMU 807401 © harmonia mundi da pacem Motets by Arvo Pärt his collection of shorter sacred works by Arvo texts? What for example is the listeners’ opinion of Mary including instrumental music (perhaps especially Pärt includes some of his newest compositions as and her song [cf. -

Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Mixed Company Theatre of Voices London Sinfonietta Paul Hillier Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen 1

Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Mixed Company Theatre of Voices London Sinfonietta Paul Hillier Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen 1. Run (2012) . For ten players . .6:20 2. Turn II (2012) . For 4 voices, flute, harp, guitar, and percussion ���������������14:50 Mixed Company 3. Song (2010) . For 4 voices . 11:32 Theatre of Voices 4. Play (2010, rev. 2012). For 14 instruments . .10:39 Else Torp, soprano 5. Sound I (2011). For 4 voices . .5:32 Signe Asmussen, mezzo-soprano Chris Watson, tenor 6. Sound II (2012) . For 4 voices . 7:31 Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass 7. Company (2010). For 4 voices and 14 instruments . 11:21 London Sinfonietta Total: 67:44 Ileana Ruhemann, flute Timothy Lines, clarinet John orford, bassoon World premiere recording. Recorded live in The Black Diamond, Copenhagen. Elise Campbell, horn Robert Holliday, trombone Jonathan Morton, violin I Joan Atherton, violin II Steve Burnard, viola Zoë Martlew, cello Enno Senft, double bass Helen Tunstall, harp Timothy Palmer, percussion oliver Lowe, percussion Steve Smith, guitar Paul Hillier, conductor Dacapo is supported by the Danish Arts Foundation Committee “Mixed Company”: The company foregathered to play PLAY and CoMPANY is a mixed company of two different ensembles from two different countries, united by the happy example of Dowland’s wanderings four centuries ago. The music stems from the pens of two contrarian composers: a contemporary Dane writing for an English instrumental ensemble and a Danish vocal group that is both Danish and English, and the aforementioned Englishman whose most famous SoNG – Lacrimae – was most likely composed in Denmark. We find ourselves therefore in very mixed company, with all the many pleasant undertones that such a phrase can evoke, in which the SoUNDs of Dowland’s tears TURN about, first setting the mood and then changing it. -

Arvo Pärt's Te Deum

Arvo Pärt’s Te Deum : A Compositional Watershed STUART GREENBAUM Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (by thesis and musical composition) July 1999 Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne Abstract A critical analysis of Arvo Pärt’s Te Deum (1984-85) is conducted in light of his tintinnabuli style. The origin of this style is traced back to 1976, placing Te Deum in the middle of the tintinnabuli period. Te Deum is a major work lasting nearly half an hour, written for three choirs, strings, prepared piano and tape. The introduction to the thesis provides an overview of the composer and styles with which he is aligned. Definitions of minimalism, spiritual minimalism and tonality are contextualised, with reference to Pärt’s compositional technique, aesthetic and development. The work is analysed syntactically and statistically in terms of its harmonic mode, its textural state and orchestration, its motivic construction, and the setting of the Te Deum text. The syntactic function of these parameters are viewed in dialectical terms. Analysis is conducted from the phenomenological standpoint of the music ‘as heard’, in conjunction with the score. Notions of elapsed time and perceived time, together with acoustical space, are considered in the course of the analysis. The primary sound recording is compared to other sound recordings, together with earlier versions of the score and revisions that have accordingly taken place. The composer, Arvo Pärt, was interviewed concerning the work, and the analysis of that work. Pärt’s responses are considered in conjunction with other interviews to determine why he pursued or tackled some questions more than others. -

BENT SØRENSEN Snowbells Works for Choir

BENT SØRENSEN Snowbells Works for choir Danish National Vocal Ensemble; Paul Hillier, conductor BENT SØRENSEN Snowbells Gråfødt (Greyborn) (2009) �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3:32 Works for choir for choir (2009) �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2:25 Danish National Vocal Ensemble; Paul Hillier, conductor Livet og døden (Life and death) for choir 3 Motets (1985) for choir �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4:54 I� Sicut umbra cum declinat �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2:29 II� Induti sunt arietes ovium� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 0:43 III� Dies mei sicut umbra declinaverunt �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 1:42 Sneeklokken (The snowbell) (2009; 2014) � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4:02 for solo voice (Adam Riis, tenor) Lacrimosa (1985) �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5:20 for choir Sneklokker (Snowbells) (2009-10) 8 movements for 5 voices and church bells �� � � � � � � -

Masterclasses 2021 Will Select the Number of Participants in the Masterclasses Will Be Around 15 Participants Who Will Form the European Limited to 7 Per Class

European Hanseatic Ensemble Application Theteachersofthemasterclasses2021willselect The number of participants in the masterclasses will be around 15 participants who will form the European limited to 7 per class. In the event that there are more Hanseatic Ensemble and will tour hanseatic cities in applicants than available places, selection will be determined thesummerof2022undertheartisticdirectionof upon evaluation of the provided audio material. Manfred Cordes. For those who will participate in the Application deadline: April 30th 2021 concerts, the course fee will be refunded and a daily INTERNATIONAL rate will be payed for rehearsal and concert days. The online application form and information about Resulting travel and accommodation expenses will transfer of the audio files (not exceeding 15 minutes in MASTERCLASSES be covered as well. total) is available on our website www.hanseatic-ensemble.eu/en/masterclasses 2021 Thespecificconcertprogrammefor2022willbe adapted to the structure of the ensemble, thus will All applicants will be informed about possible Soloandensemblemusicaround1600 be developed after the selection of the ensemble participationbyJune15th2021atthelatest.Ifyouare members. The goal is a balanced distribution of selected, we kindly request that you pay the course fee of September 20th - 23rd 2021 singers, string, wind and continuo players which will 150€byJuly15th2021. allow for the performance of multi-choral works. in Lübeck We have booked budget accommodation for you in Lübeck (DJH Youth hostel), however costs for travel, Ulrike Hofbauer · Voice accommodation (youth hostel, hotel, etc.) and meals are Jan Van Elsacker · Voice to be absorbed by the participants. -

S P R I N G 2 0

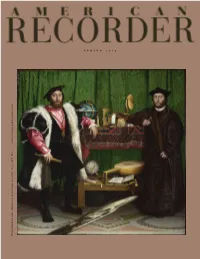

Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. LIV, No. 1 • www.americanrecorder.org spring 2013 SOPRANINO TO SUBBA SS A WELL-TUNED CON S ORT www.moeck.com Anzeige_Orgel_A4.indd 1 11.11.2008 19:21:44 Uhr Lost in Time Press New works and arrangements for recorder ensemble Compositions by Frances Blaker Paul Ashford Hendrik de Regt and others Inquiries: Corlu Collier PMB 309 2226 N Coast Hwy Newport, Oregon 97365 www.lostintimepress.com [email protected] Dream-Edition – for the demands of a soloist Enjoy the recorder Mollenhauer & Adriana Breukink Enjoy the recorder Dream Recorders for the demands of a soloist New: due to their characteristic wide bore and full round sound Dream-Edition recorders are also suitable for demanding solo recorder repertoire. These hand-finished instru- ments in European plumwood with maple decorative rings combine a colourful rich sound with a stable tone. Baroque fingering and double holes provide surprising agility. TE-4118 Tenor recorder with ergonomic- ally designed keys: • Attractive shell-shaped keys • Robust mechanism • Fingering changes made TE-4318 easy by a roll mechanism fitted to double keys • Well-balanced sound a1 = 442 Hz Soprano and alto in luxurious leather bag, tenor in a hard case TE-4428 www.mollenhauer.com Soprano Alto Tenor (with double key) TE-4118 Plumwood with maple TE-4318 Plumwood with maple TE-4428 Plumwood with maple decorative rings decorative rings decorative rings Editor’s ______Note ______ ______ ______ ______ Volume LIV, Number 1 Spring 2013 efore you ask: yes, that’s a skull on the Features cover of this issue.