Diversification and Change in South Halmahera–West New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plural Words in Austronesian Languages: Typology and History

Plural Words in Austronesian Languages: Typology and History A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Research Master of Arts in Linguistics by Jiang Wu Student ID: s1609785 Supervisor: Prof. dr. M.A.F. Klamer Second reader: Dr. E.I. Crevels Date: 10th January, 2017 Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University Table of contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... iv List of tables ................................................................................................................... v List of figures ................................................................................................................ vi List of maps ................................................................................................................. vii List of abbreviations .................................................................................................. viii Chapter 1. Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2. Background literature ................................................................................... 3 2.1. Plural words as nominal plurality marking ....................................................... 3 2.2. Plural words in Austronesian languages .......................................................... -

Ports of New Guinea Revisited (A Trip Down Memory Lane)

Ports of New Guinea Revisited (A Trip Down Memory Lane) Not named the “Paradise Islands” without due reason. Papua New Guinea and its outlaying islands must rank amongst the top in the global scale of beauty for both Fauna and Flora, not to mention the pristine Aquatic attributes these islands possess. If crystal blue water, silver sandy beaches, swaying palms, coral reefs, lush tropical rainforest, reptiles, and birds together with a country steeped in history and culture stokes your imagination, then this should become your choice of destination. It is true that Papua New Guinea is not blessed with an extensive infrastructure of highways and good roads and the only realistic way to explore these islands is by light aircraft, or better still, by ship. I spent a memorable 4-5 years of my sea-going career in the Pacific Islands, including New Guinea, and it is based on my observations and experiences that this narration is derived. During the 1970s and early 80s I was fortunate to have the opportunity to sail around these waters in my capacity as a professional seafarer. It covered a relatively short period, but it was a time of great adventure and feeling of exploration, bearing in mind that during those years New Guinea was completely unspoiled by the influences of Western society and retained much more mystique and feeling of the “unknown” compared to today. What follows is a personal recap and description, of what I can remember of those years I spent in the region. Map showing main Ports of New Guinea DARU Island - this is a small elliptical island close to the mainland in the western region of Papua New Guinea. -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

Languages of Flores

Are the Central Flores languages really typologically unusual? Alexander Elias January 13, 2020 1 Abstract The isolating languages of Central Flores (Austronesian) are typologically distinct from their nearby relatives. They have no bound morphology, as well elaborate numeral clas- sifier systems, and quinary-decimal numeral system. McWhorter (2019) proposes that their isolating typology is due to imperfect adult language acquisition of a language of Sulawesi, brought to Flores by settlers from Sulawesi in the relatively recent past. I pro- pose an alternative interpretation, which better accounts for the other typological features found in Central Flores: the Central Flores languages are isolating because they have a strong substrate influence from a now-extinct isolating language belonging to the Mekong- Mamberamo linguistic area (Gil 2015). This explanation better accounts for the typological profile of Central Flores and is a more plausible contact scenario. Keywords: Central Flores languages, Eastern Indonesia, isolating languages, Mekong- Mamberamo linguistic area, substrate influence 2 Introduction The Central Flores languages (Austronesian; Central Malayo-Polynesian) are a group of serialising SVO languages with obligatory numeral classifier systems spoken on the island of Flores, one of the Lesser Sunda Islands in the east of Indonesia. These languages, which are almost completely lacking in bound morphology, include Lio, Ende, Nage, Keo, Ngadha and Rongga. Taken in their local context, this typological profile is unusual: other Austronesian languages of eastern Indonesia generally have some bound morphology and non-obligatory numeral classifier systems. However, in a broader view, the Central Flores languages are typologically similar to many of the isolating languages of Mainland Southeast Asia and Western New Guinea, many of which are also isolating, serialising SVO languages with obligatory numeral classifier systems. -

Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania

Abstract of http://www.uog.ac.pg/glec/thesis/ch1web/ABSTRACT.htm Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania by Glendon A. Lean In modern technological societies we take the existence of numbers and the act of counting for granted: they occur in most everyday activities. They are regarded as being sufficiently important to warrant their occupying a substantial part of the primary school curriculum. Most of us, however, would find it difficult to answer with any authority several basic questions about number and counting. For example, how and when did numbers arise in human cultures: are they relatively recent inventions or are they an ancient feature of language? Is counting an important part of all cultures or only of some? Do all cultures count in essentially the same ways? In English, for example, we use what is known as a base 10 counting system and this is true of other European languages. Indeed our view of counting and number tends to be very much a Eurocentric one and yet the large majority the languages spoken in the world - about 4500 - are not European in nature but are the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas. If we take these into account we obtain a quite different picture of counting systems from that of the Eurocentric view. This study, which attempts to answer these questions, is the culmination of more than twenty years on the counting systems of the indigenous and largely unwritten languages of the Pacific region and it involved extensive fieldwork as well as the consultation of published and rare unpublished sources. -

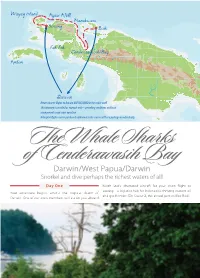

Darwin/West Papua/Darwin Snorkel and Dive Perhaps the Richest Waters of All!

Wayag Island Ayau Atoll Manokwari Sorong Biak Fak Fak Cenderawasih Bay Ambon Darwin Return charter flights ex Darwin ARE INCLUDED in the cruise tariff. This itinerary is provided as example only – prevailing conditions and local arrangements may cause variation. Helicopter flights can be purchased additional to the cruise tariff as a package or individually. TheWhale Sharks of Cenderawasih Bay Darwin/West Papua/Darwin Snorkel and dive perhaps the richest waters of all! Day One North Star’s chartered aircraft for your short flight to Sorong – a logistics hub for Indonesia’s thriving eastern oil Your adventure begins amidst the tropical charm of and gas frontier (On Cruise 2, the arrival port will be Biak). Darwin. One of our crew members will escort you aboard Sorong is also where we will welcome you aboard the spearfishing to collecting eatable worms from the magnificent TRUE NORTH. powdery-white sand beaches. The atoll is surrounded by crystal clear water that is frequented by large pods of Enjoy a welcome aboard cocktail as we begin to cruise dolphins. The outer-reef drops sharply to over 1000m and through the equally magnificent Raja Ampat archipelago. clouds of beautiful fishes carpet the reef walls. We’ll have Located off the northwest tip of Bird’s Head Peninsula a chance to snorkel and dive at several sites around the on the island of New Guinea, in Indonesia’s West Papua atoll, or you can head off to the big-blue (outside the Ayau province, Raja Ampat, or the Four Kings, is an archipelago Marine Park) to try your luck at some deep water trolling. -

The Position of Enggano Within Austronesian

7KH3RVLWLRQRI(QJJDQRZLWKLQ$XVWURQHVLDQ 2ZHQ(GZDUGV Oceanic Linguistics, Volume 54, Number 1, June 2015, pp. 54-109 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL L3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ol/summary/v054/54.1.edwards.html Access provided by Australian National University (24 Jul 2015 10:27 GMT) The Position of Enggano within Austronesian Owen Edwards AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Questions have been raised about the precise genetic affiliation of the Enggano language of the Barrier Islands, Sumatra. Such questions have been largely based on Enggano’s lexicon, which shows little trace of an Austronesian heritage. In this paper, I examine a wider range of evidence and show that Enggano is clearly an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian (MP) subgroup. This is achieved through the establishment of regular sound correspondences between Enggano and Proto‒Malayo-Polynesian reconstructions in both the bound morphology and lexicon. I conclude by examining the possible relations of Enggano within MP and show that there is no good evidence of innovations shared between Enggano and any other MP language or subgroup. In the absence of such shared innovations, Enggano should be considered one of several primary branches of MP. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 Enggano is an Austronesian language spoken on the southernmost of the Barrier Islands off the west coast of the island of Sumatra in Indo- nesia; its location is marked by an arrow on map 1. The genetic position of Enggano has remained controversial and unresolved to this day. Two proposals regarding the genetic classification of Enggano have been made: 1. -

Comparatives in Melanesia: Concentric Circles of Convergence Antoinette Schapper, Lourens De Vries

Comparatives in Melanesia: Concentric circles of convergence Antoinette Schapper, Lourens de Vries To cite this version: Antoinette Schapper, Lourens de Vries. Comparatives in Melanesia: Concentric circles of conver- gence. Linguistic Typology, De Gruyter, 2018, 22 (3), pp.437-494. 10.1515/lingty-2018-0015. halshs- 02931152 HAL Id: halshs-02931152 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02931152 Submitted on 4 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Linguistic Typology 2018; 22(3): 437–494 Antoinette Schapper and Lourens de Vries Comparatives in Melanesia: Concentric circles of convergence https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2018-0015 Received May 02, 2018; revised July 26, 2018 Abstract: Using a sample of 116 languages, this article investigates the typology of comparative constructions and their distribution in Melanesia, one of the world’s least-understood linguistic areas. We present a rigorous definition of a comparative construction as a “comparative concept”, thereby excluding many constructions which have been considered functionally comparatives in Melanesia. Conjoined comparatives are shown to dominate at the core of the area on the island of New Guinea, while (monoclausal) exceed comparatives are found in the maritime regions around New Guinea. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

Journal of Arts & Humanities

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 10, 2020: 40-48 Article Received: 06-10-2020 Accepted: 19-10-2020 Available Online: 29-10-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.18533/jah.v9i10.1990 The Codification of Native Papuan Languages in the West Papua Province: Identification and Classification of Native Papuan Languages Warami Hugo1 ABSTRACT This study aims to discuss how regional languages as the local language of Indigenous Papuans (OAP) in West Papua Province can be codified at this time or at least approach the ideal situation identified and classified by the State (government), so that local languages can be documented accurately and right. Starting from the idea that the extinction of a language causes the loss of various forms of cultural heritage, especially the customary heritage and oral expressions of the speaking community. There are two main problems in this study, namely: (1) Identification of the regional language of indigenous Papuans in West Papua Province, and (2) Classification of regional languages of indigenous Papuans in West Papua Province. This study uses two approaches, namely (1) a theoretical approach and (2) a methodological approach. The theoretical approach is an exploration of the theory of language documentation, while the methodological approach is a descriptive approach with an explanative dimension. This study follows the procedures of (1) the data provision stage, (2) the data analysis stage, and (3) the data analysis presentation stage. The findings in this study illustrate that the languages in West Papua Province can be grouped into four language groups, namely (1) Austronesian phylum groups; (2) West Papua phylum group; (3) Papuan Bird Head phylum group; and (4) the Trans West Papua Phylum Group. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Marine Pollution Bulletin 64 (2012) 2279–2295

Marine Pollution Bulletin 64 (2012) 2279–2295 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul Review Papuan Bird’s Head Seascape: Emerging threats and challenges in the global center of marine biodiversity ⇑ Sangeeta Mangubhai a, , Mark V. Erdmann b,j, Joanne R. Wilson a, Christine L. Huffard b, Ferdiel Ballamu c, Nur Ismu Hidayat d, Creusa Hitipeuw e, Muhammad E. Lazuardi b, Muhajir a, Defy Pada f, Gandi Purba g, Christovel Rotinsulu h, Lukas Rumetna a, Kartika Sumolang i, Wen Wen a a The Nature Conservancy, Indonesia Marine Program, Jl. Pengembak 2, Sanur, Bali 80228, Indonesia b Conservation International, Jl. Dr. Muwardi 17, Renon, Bali 80235, Indonesia c Yayasan Penyu Papua, Jl. Wiku No. 124, Sorong West Papua 98412, Indonesia d Conservation International, Jl. Kedondong Puncak Vihara, Sorong, West Papua 98414, Indonesia e World Wide Fund for Nature – Indonesia Program, Graha Simatupang Building, Tower 2 Unit C 7th-11th Floor, Jl. TB Simatupang Kav C-38, Jakarta Selatan 12540, Indonesia f Conservation International, Jl. Batu Putih, Kaimana, West Papua 98654, Indonesia g University of Papua, Jl. Gunung Salju, Amban, Manokwari, West Papua 98314, Indonesia h University of Rhode Island, College of Environmental and Life Sciences, Department of Marine Affairs, 1 Greenhouse Road, Kingston, RI 02881, USA i World Wide Fund for Nature – Indonesia Program, Jl. Manggurai, Wasior, West Papua, Indonesia j California Academy of Sciences, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA article info abstract Keywords: The Bird’s Head Seascape located in eastern Indonesia is the global epicenter of tropical shallow water Coral Triangle marine biodiversity with over 600 species of corals and 1,638 species of coral reef fishes.