Birds of New Guinea Field Guide (Beehler Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Labile Evolution of Display Traits in Bowerbirds Indicates Reduced Effects of Phylogenetic Constraint

Labile evolution of display traits in bowerbirds indicates reduced effects of phylogenetic constraint " # # RAB KUSMIERSKI , GERALD BORGIA , ALBERT UY " ROSS H.CROZIER " School of Genetics and Human Variation, La Trobe Uniersit, Bundoora, Victoria 3083, Australia # Department of Zoolog, Uniersit of Marland, College Park, MD 20742, USA SUMMARY Bowerbirds (Ptilonorhynchidae) have among the most exaggerated sets of display traits known, including bowers, decorated display courts and bright plumage, that differ greatly in form and degree of elaboration among species. Mapping bower and plumage traits on an independently derived phylogeny constructed from mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences revealed large differences in display traits between closely related species and convergences in both morphological and behavioural traits. Plumage characters showed no effect of phylogenetic inertia, although bowers exhibited some constraint at the more fundamental level of design, but above which they appeared free of constraint. Bowers and plumage characters, therefore, are poor indicators of phylogenetic relationship in this group. Testing Gilliard’s (1969) transferral hypothesis indicated some support for the idea that the focus of display has shifted from bird to bower in avenue-building species, but not in maypole-builders or in bowerbirds as a whole. maypole-builders (Amblornis, four spp.; Prionodura) in- 1. INTRODUCTION clude the orange-crested males of A. macgregoriae, which Bowerbirds (Ptilonorhynchidae) form a monophyletic decorate a sapling with horizontally interwoven sticks. family (Kusmierski et al. 1993) (eight genera, 19 species) The dull-coloured, monomorphic A. inornatus of endemic to Australia and New Guinea, and are unique western Irian Jaya (Arfak and Wandamen mountains) in the bird world in constructing and using a bower in and the orange-crested, dimorphic A. -

Evolution of Correlated Complexity in the Radically Different Courtship Signals of Birds-Of-Paradise

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/351437; this version posted June 20, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Evolution of correlated complexity in the radically different courtship signals of birds-of-paradise 5 Russell A. Ligon1,2*, Christopher D. Diaz1, Janelle L. Morano1, Jolyon Troscianko3, Martin Stevens3, Annalyse Moskeland1†, Timothy G. Laman4, Edwin Scholes III1 1- Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Rd, Ithaca, NY, USA. 10 2- Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA. 3- Centre for Ecology and Conservation, College of Life and Environmental Science, University of Exeter, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9FE, UK 4- Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 15 † Current address: Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, UK *Author for correspondence: [email protected] ORCID: Russell Ligon https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0195-8275 20 Janelle Morano https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5950-3313 Edwin Scholes https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7724-3201 [email protected] [email protected] 25 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 30 keywords: ornament, complexity, behavioral analyses, sensory ecology, phenotypic radiation 35 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/351437; this version posted June 20, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Management and Breeding of Birds of Paradise (Family Paradisaeidae) at the Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation

Management and breeding of Birds of Paradise (family Paradisaeidae) at the Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation. By Richard Switzer Bird Curator, Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Presentation for Aviary Congress Singapore, November 2008 Introduction to Birds of Paradise in the Wild Taxonomy The family Paradisaeidae is in the order Passeriformes. In the past decade since the publication of Frith and Beehler (1998), the taxonomy of the family Paradisaeidae has been re-evaluated considerably. Frith and Beehler (1998) listed 42 species in 17 genera. However, the monotypic genus Macgregoria (MacGregor’s Bird of Paradise) has been re-classified in the family Meliphagidae (Honeyeaters). Similarly, 3 species in 2 genera (Cnemophilus and Loboparadisea) – formerly described as the “Wide-gaped Birds of Paradise” – have been re-classified as members of the family Melanocharitidae (Berrypeckers and Longbills) (Cracraft and Feinstein 2000). Additionally the two genera of Sicklebills (Epimachus and Drepanornis) are now considered to be combined as the one genus Epimachus. These changes reduce the total number of genera in the family Paradisaeidae to 13. However, despite the elimination of the 4 species mentioned above, 3 species have been newly described – Berlepsch's Parotia (P. berlepschi), Eastern or Helen’s Parotia (P. helenae) and the Eastern or Growling Riflebird (P. intercedens). The Berlepsch’s Parotia was once considered to be a subspecies of the Carola's Parotia. It was previously known only from four female specimens, discovered in 1985. It was rediscovered during a Conservation International expedition in 2005 and was photographed for the first time. The Eastern Parotia, also known as Helena's Parotia, is sometimes considered to be a subspecies of Lawes's Parotia, but differs in the male’s frontal crest and the female's dorsal plumage colours. -

Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No

AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Working Paper No. 6 MILNE BAY PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.L. Hide, R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, T. Betitis, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, L. Kurika, E. Lowes, D.K. Mitchell, S.S. Rangai, M. Sakiasi, G. Sem and B. Suma Department of Human Geography, The Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 Correct Citation: Hide, R.L., Bourke, R.M., Allen, B.J., Betitis, T., Fritsch, D., Grau, R., Kurika, L., Lowes, E., Mitchell, D.K., Rangai, S.S., Sakiasi, M., Sem, G. and Suma,B. (2002). Milne Bay Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No. 6. Land Management Group, Department of Human Geography, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra. Revised edition. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry: Milne Bay Province: text summaries, maps, code lists and village identification. Rev. ed. ISBN 0 9579381 6 0 1. Agricultural systems – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. 2. Agricultural geography – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. 3. Agricultural mapping – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. I. Hide, Robin Lamond. II. Australian National University. Land Management Group. (Series: Agricultural systems of Papua New Guinea working paper; no. 6). 630.99541 Cover Photograph: The late Gore Gabriel clearing undergrowth from a pandanus nut grove in the Sinasina area, Simbu Province (R.L. -

Bird List Column A: We Should Encounter (At Least a 90% Chance) Column B: May Encounter (About a 50%-90% Chance) Column C: Possible, but Unlikely (20% – 50% Chance)

THE PHILIPPINES Prospective Bird List Column A: we should encounter (at least a 90% chance) Column B: may encounter (about a 50%-90% chance) Column C: possible, but unlikely (20% – 50% chance) A B C Philippine Megapode (Tabon Scrubfowl) X Megapodius cumingii King Quail X Coturnix chinensis Red Junglefowl X Gallus gallus Palawan Peacock-Pheasant X Polyplectron emphanum Wandering Whistling Duck X Dendrocygna arcuata Eastern Spot-billed Duck X Anas zonorhyncha Philippine Duck X Anas luzonica Garganey X Anas querquedula Little Egret X Egretta garzetta Chinese Egret X Egretta eulophotes Eastern Reef Egret X Egretta sacra Grey Heron X Ardea cinerea Great-billed Heron X Ardea sumatrana Purple Heron X Ardea purpurea Great Egret X Ardea alba Intermediate Egret X Ardea intermedia Cattle Egret X Ardea ibis Javan Pond-Heron X Ardeola speciosa Striated Heron X Butorides striatus Yellow Bittern X Ixobrychus sinensis Von Schrenck's Bittern X Ixobrychus eurhythmus Cinnamon Bittern X Ixobrychus cinnamomeus Black Bittern X Ixobrychus flavicollis Black-crowned Night-Heron X Nycticorax nycticorax Western Osprey X Pandion haliaetus Oriental Honey-Buzzard X Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard X Pernis celebensis Black-winged Kite X Elanus caeruleus Brahminy Kite X Haliastur indus White-bellied Sea-Eagle X Haliaeetus leucogaster Grey-headed Fish-Eagle X Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com -

Two New Species of Paraphilopterus Mey, 2004 (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera: Philopteridae)

Zootaxa 3873 (2): 155–164 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3873.2.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D78B845A-99D8-423E-B520-C3DD83E3C87F Two new species of Paraphilopterus Mey, 2004 (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera: Philopteridae) from New Guinean bowerbirds (Passeriformes: Ptilonorhynchidae) and satinbirds (Passeriformes: Cnemophilidae) DANIEL R. GUSTAFSSON1,2 & SARAH E. BUSH1 1Department of Biology, University of Utah, 257 S. 1400 E., Salt Lake City, Utah, 84112, USA 2Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Two new species of Paraphilopterus Mey, 2004 are described and named. Paraphilopterus knutieae n. sp. is described from two subspecies of Macgregor's bowerbirds: Amblyornis macgregoriae nubicola Schodde & McKean, 1973 and A. m. kombok Schodde & McKean, 1973, and Sanford's bowerbird: Archboldia sanfordi (Mayr & Gilliard, 1950) (Ptilono- rhynchidae). Paraphilopterus meyi n. sp. is described from two subspecies of crested satinbirds: Cnemophilus macgrego- rii macgregorii De Vis, 1890 and C. m. sanguineus Iredale, 1948 (Cnemophilidae). These new louse species represent the first records of the genus Paraphilopterus outside Australia, as well as from host families other than the Corcoracidae. The description of Paraphilopterus is revised and expanded based on the additional new species, including the first de- scription of the male of this genus. Also, we provide a key to the species of Paraphilopterus. Key words: Phthiraptera, Ischnocera, Philopteridae, Paraphilopterus, chewing lice, new species, Ptilonorhynchidae, Cnemophilidae, New Guinea Introduction Mey (2004: 188) described the new genus Paraphilopterus based on a single female louse from the Australian host Corcorax melanoramphos (Vieillot, 1817) (Corcoracidae). -

Relationship of Bird Diversity and Plant Composition Inside the Area Campus Green Space of Universitas Padjadjaran Jatinangor, Sumedang West Java

Biosaintifika 10 (3) (2018) 500-509 Biosaintifika Journal of Biology & Biology Education http://journal.unnes.ac.id/nju/index.php/biosaintifika Relationship of Bird Diversity and Plant Composition Inside The Area Campus Green Space of Universitas Padjadjaran Jatinangor, Sumedang West Java Deden Nurjaman, Teguh Husodo, Erri Noviar Megantara, Herri Y. Hadikusumah, Indri Wulandari DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15294/biosaintifika.v10i3.13543 Department of Biology, Postgraduate Programme of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia History Article Abstract Received 26 February 2018 Padjadjaran University (UNPAD) Jatinangor is currently conducting green Cam- Approved 19 September 2018 pus program. To support the program, a study of biota living in it, as one of the Published 31 December 2018 benchmarks of good or bad environmental conditions, is needed. The green space of Jatinangor Campus is divided into two clusters namely Cluster I green space Keywords (Campus Forest) and green space Cluster II (Campus Non Forest). The objective of birds; composition the research was to know the relationship between diversity of birds with diversity of plants; UNPAD of plants in the green space of Cluster I (Campus Forest) and Cluster II (Campus Non Forest) UNPAD Campus Jatinangor as one of the parameters of successful development of green Campus. This research is descriptive-explorative with census method on bird species and plant composition from green spaces of Cluster I (Cam- pus Forest) and Cluste II (Campus Non Forest) Campus UNPAD Jatinangor. From the observations in Cluster I, we identified 46 species of birds and 77 species of plants, whereas in Cluster II, we identified 32 species of birds and 74 types of plants. -

PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework September 2015 PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea This environmental assessment and review framework is a document of the borrower/recipient. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Project information, including draft and final documents, will be made available for public review and comment as per ADB Public Communications Policy 2011. The environmental assessment and review framework will be uploaded to ADB website and will be disclosed locally. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. ii 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 A. BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................................... -

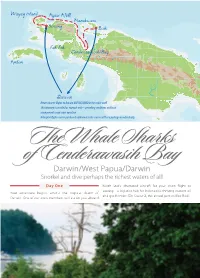

Darwin/West Papua/Darwin Snorkel and Dive Perhaps the Richest Waters of All!

Wayag Island Ayau Atoll Manokwari Sorong Biak Fak Fak Cenderawasih Bay Ambon Darwin Return charter flights ex Darwin ARE INCLUDED in the cruise tariff. This itinerary is provided as example only – prevailing conditions and local arrangements may cause variation. Helicopter flights can be purchased additional to the cruise tariff as a package or individually. TheWhale Sharks of Cenderawasih Bay Darwin/West Papua/Darwin Snorkel and dive perhaps the richest waters of all! Day One North Star’s chartered aircraft for your short flight to Sorong – a logistics hub for Indonesia’s thriving eastern oil Your adventure begins amidst the tropical charm of and gas frontier (On Cruise 2, the arrival port will be Biak). Darwin. One of our crew members will escort you aboard Sorong is also where we will welcome you aboard the spearfishing to collecting eatable worms from the magnificent TRUE NORTH. powdery-white sand beaches. The atoll is surrounded by crystal clear water that is frequented by large pods of Enjoy a welcome aboard cocktail as we begin to cruise dolphins. The outer-reef drops sharply to over 1000m and through the equally magnificent Raja Ampat archipelago. clouds of beautiful fishes carpet the reef walls. We’ll have Located off the northwest tip of Bird’s Head Peninsula a chance to snorkel and dive at several sites around the on the island of New Guinea, in Indonesia’s West Papua atoll, or you can head off to the big-blue (outside the Ayau province, Raja Ampat, or the Four Kings, is an archipelago Marine Park) to try your luck at some deep water trolling. -

Nest, Egg, Incubation Behaviour and Parental Care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis Germana

Australian Field Ornithology 2019, 36, 18–23 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo36018023 Nest, egg, incubation behaviour and parental care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana Richard H. Donaghey1, 2*, Donna J. Belder3, Tony Baylis4 and Sue Gould5 1Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan 4111 QLD, Australia 280 Sawards Road, Myalla TAS 7325, Australia 3Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 4628 Utopia Road, Brooweena QLD 4621, Australia 5269 Burraneer Road, Coomba Park NSW 2428, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana, recently elevated to species status, is endemic to montane forests on the Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. The polygynous males in the Yopno Urawa Som Conservation Area build distinctive maypole bowers. We document for the first time the nest, egg, incubation behaviour, and parental care of this species. Three of the five nests found were built in tree-fern crowns. Nest structure and the single-egg clutch were similar to those of MacGregor’s Bowerbird A. macgregoriae. Only the female Huon Bowerbird incubated. Mean length of incubation sessions was 30.9 minutes and the number of sessions daily was 18. Diurnal incubation constancy over a 12-hour day was 74%, compared with a mean of ~70% in six other members of the bowerbird family. The downy nestling resembled that of MacGregor’s Bowerbird. Vocalisations of a female Huon Bowerbird at a nest with a nestling -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

Exploring Material Culture Distributions in the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea

Gender, mobility and population history: exploring material culture distributions in the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea by Andrew Fyfe, BA (Hons) Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Discipline of Geographical and Environmental Studies The University of Adelaide November 2008 …..These practices, then, and others which I will speak of later, were borrowed by the Greeks from Egypt. This is not the case, however, with the Greek custom of making images of Hermes with the phallus erect; it was the Athenians who took this from the Pelasgians, and from the Athenians the custom spread to the rest of Greece. For just at the time when the Athenians were assuming Hellenic nationality, the Pelasgians joined them, and thus first came to be regarded as Greeks. Anyone will know what I mean if he is familiar with the mysteries of the Cabiri-rites which the men of Samothrace learned from the Pelasgians, who lived in that island before they moved to Attica, and communicated the mysteries to the Athenians. This will show that the Athenians were the first Greeks to make statues of Hermes with the erect phallus, and that they learned the practice from the Pelasgians…… Herodotus c.430 BC ii Table of contents Acknowledgements vii List of figures viii List of tables xi List of Appendices xii Abstract xiv Declaration xvi Section One 1. Introduction 2 1.1 The Upper Sepik-Central New Guinea Project 2 1.2 Lapita and the exploration of relationships between language and culture in Melanesia 3 1.3 The quantification of relationships between material culture and language on New Guinea’s north coast 6 1.4 Thesis objectives 9 2.