Reviews Marvels & Tales Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 by CLAUDIA MAREIKE

ROMANTICISM, ORIENTALISM, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 By CLAUDIA MAREIKE KATRIN SCHWABE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Claudia Mareike Katrin Schwabe 2 To my beloved parents Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisory committee chair, Dr. Barbara Mennel, who supported this project with great encouragement, enthusiasm, guidance, solidarity, and outstanding academic scholarship. I am particularly grateful for her dedication and tireless efforts in editing my chapters during the various phases of this dissertation. I could not have asked for a better, more genuine mentor. I also want to express my gratitude to the other committee members, Dr. Will Hasty, Dr. Franz Futterknecht, and Dr. John Cech, for their thoughtful comments and suggestions, invaluable feedback, and for offering me new perspectives. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the abundant support and inspiration of my friends and colleagues Anna Rutz, Tim Fangmeyer, and Dr. Keith Bullivant. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my family, particularly my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe, as well as to my brother Marius and his wife Marina Schwabe. Many thanks also to my dear friends for all their love and their emotional support throughout the years: Silke Noll, Alice Mantey, Lea Hüllen, and Tina Dolge. In addition, Paul and Deborah Watford deserve special mentioning who so graciously and welcomingly invited me into their home and family. Final thanks go to Stephen Geist and his parents who believed in me from the very start. -

THE ARABIAN NIGHTS in ENGLISH LITERATURE the Arabian Nights in English Literature

THE ARABIAN NIGHTS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE The Arabian Nights in English Literature Studies in the Reception of The Thousand and One Nights into British Culture Edited by Peter L. Caracciolo Lecturer in English Royal Holloway and Bedford New College University of London M MACMILLAN PRESS ©Peter L. Caracciolo 1988 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1988 978-0-333-36693-6 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended), or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 33-4 Alfred Place, London WClE 7DP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1988 Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world Typeset by Wessex Typesetters (Division of The Eastem Press Ltd) Frome, Somerset British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data The Arabian Nights in English literature: Studies in the reception of The Thousand and One Nights into British culture. 1. English literature-History and criticism I. Caracciolo, Peter L. 820.9 PR83 ISBN 978-1-349-19622-7 ISBN 978-1-349-19620-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-19620-3 In memoriam Allan Grant Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface and Acknowledgements xiii Notes on the Contributors xxvi A Note on Orthography xxviii To Scheherazade GREVEL LINDOP xxix 1 Introduction: 'Such a store house of ingenious fiction and of splendid imagery' 1 PETER L. -

MA Thesis Final Draft

“YOUR WISH IS MY COMMAND” AND OTHER FICTIONS: RELUCTANT POSSESSIONS IN RICHARD BURTON’S “ALADDIN” By Dan Fang Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in English August, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Rachel Teukolsky Dana Nelson The Arabian Nights Entertainments is a work of fantasy, mystery, and the imagination. In it we find bewitching princesses, strange beasts, terrifying jinnis, and epic voyages; from it we draw stories and images that fill our culture with wonder. Since its introduction to the West by Antoine Galland in 1704, stories from the Nights have been rewritten and reworked into everything from children’s stories to operas, musicals to movies. Of all of the stories from the Nights—which consist of more than 400 that a clever girl, Scheherazade, tells to her husband the Sultan over a thousand and one nights in order to stay her execution—the stories of Aladdin and his magical lamp, Ali Baba and his forty thieves, and Sinbad and his seven voyages are arguably the most popular. And since the production of Disney’s 1992 animated feature film, “Aladdin” has become perhaps the most popular of the tales in Western culture. The popularity of “Aladdin” is not a late 20th Century phenomenon, however. Aside from versions of Scheherazade’s own story, “Aladdin” was the first to be incorporated into the British theater.1 Throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries, “Aladdin” has been incorporated into countless collections of children’s bedtime stories, picture books both cheaply accessible and gloriously exquisite, even into handbooks for English instruction in grammar schools. -

RABIAH ZAMANI SIDDIQUI, Dr. SHUCHI SRIVASTAVA

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.6.Issue 3. 2018 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (July-Sept) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE THE EARLY EUROPEAN TRANSLATIONS OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS RABIAH ZAMANI SIDDIQUI1, Dr. SHUCHI SRIVASTAVA2 1All Saints' School, Idgah Hills, Bhopal 2Professor, MANIT, Bhopal ABSTRACT The chief focus of this article is not to tell the story of the Nights’ history and its MS sources, but rather to consider what happened after the Nights reached Europe. Published in 1704-1716, Antoine Galland’s Les Milles et Une Nuits: contes arabes traduits en Français (The One Thousand and One Nights: Arab Tales Translated in French)was nothing short of an international phenomenon. Galland’s volumes sold out instantly and even appeared in English Grub street editions well before he was finished translating them in French. Then came the translations of two Englishmen, Edward Lane’s The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, published in 1838-1840 and Sir Richard Francis Burton’s A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments Now Entituled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, published in 1885- 1888. It soon became a rare works that appealed to both the common man and the cognoscenti alike. It’s fair to remark that the Arabian Nights’ western fame was due in large part, if not entirely, to Galland, Lane, and Burton. Key words: Jinns (Genies), Orientalism, Burton’s English -

KALILA Wa DEMNA I. Redactions and Circulation in Persian Literature

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Columbia University Academic Commons KALILA wa DEMNA i. Redactions and circulation In Persian literature Kalila wa Demna has been known in different versions since the 6th century CE. KALILA wa DEMNA i. Redactions and circulation In Persian literature Kalila wa Demna has been known in different versions since the 6th century CE. The complex relations between the extant New Persian versions, a lost Sanskrit original, and a lost Middle Persian translation have been studied since 1859 when the German Indologist Theodor Benfey (1809- 1881), a pioneer of comparative folklore studies, published a translation of extant Sanskrit versions of the Pañcatantra (lit. “five topics”; for the debate about possible interpretations of the Sanskrit title, see Pañcatantra, tr. Olivelle, pp. xiii-xiv). The scholarly construction of the migration of an Indian story cycle into Near and Middle Eastern languages has received considerable attention, because the project touches on the fundamental question of how to conceive of national and international literary histories if narrative traditions have moved freely between Indo-Iranian and Semitic languages. Two philological approaches dominate the research. Johannes Hertel (1872-1955; q.v.), Mojtabā Minovi (Plate i), and others have focused on editing the earliest versions as preserved in Sanskrit and New Persian manuscripts, while Franklin Edgerton (1885-1963) and François de Blois have created 20th century synthesized versions of the lost Sanskrit and Middle Persian texts. The circulation of Kalila wa Demna in Persian literature documents how Iran mediated the diffusion of knowledge between the Indian subcontinent and the Mediterranean. -

Title: Open Sesame! : the Polish Translations of "The Thousand and One Nights"

Title: Open Sesame! : the polish Translations of "The Thousand and One Nights" Author: Marta Mamet-Michalkiewicz Citation style: Mamet-Michalkiewicz Marta. (2016). Open Sesame! : the polish Translations of "The Thousand and One Nights". W: A. Adamowicz-Pośpiech, M. Mamet-Michalkiewicz (red.), "Translation in culture" (S. 119-134). Katowice : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. Marta Mamet-Michalkiewicz UNIVERSITY OF SILESIA IN KATOWICE Open Sesame! The Polish Translations of The Thousand and One Nights ABSTRACT: The author discusses the Polish twentieth-century translations of The Thousand and One Nights indicating different translation strategies and shortcomings of the Polish versions of the book. This article also signalises the process of mythologisation, orientalisa- tion, and fairytalisation of the tales. The author indicates the need of retranslation of The Thousand and One Nights and proposes to perceive the translations of the book and its numerous versions and adaptations through the metaphor of the sesame overfilled with translation treasures which are ‘discovered’ by the reader in the act of reading. KEYWORDS: The Thousand and One Nights, Polish translations, translation, fairytalisation It would be challenging to find a reader who has not heard of Schehera- zade’s stories, Aladdin’s magic lamp, Sinbad or Ali Baba. The cycle of The Thousand and One Nights has been translated into a plethora of European languages and has been retranslated many times (also into Polish). In spite of its complex Arabic origin The Thousand and One Nights1 has been a part of the Western culture. Yet, the popularity of the book and its characters does not project onto at least superficial knowledge of this collection of stories, legends, fables, fairy-tales and, last but not least, poems. -

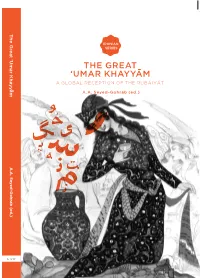

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

96232 Studia Iranica-Def.Ps

CHRISTINE VAN RUYMBEKE (UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE) MURDER IN THE FOREST: CELEBRATING REWRITINGS AND MISREADINGS OF THE KALILA-DIMNA TALE OF THE LION AND THE HARE * SUMMARY This paper considers rewritings and translations of a key-episode within the cycle of fables known as the Kalila-Dimna in several innovative ways. First, by considering the ways in which this episode has been rewritten throughout the centuries, the essay takes a stand radically opposed to the prevalent scholarship around the fables, which consists in rating WKHUHZULWLQJVIRUWKHLUIDLWKIXOQHVVWRWKHVRXUFHWH[W V 7KHSUHVHQWDSSURDFK³FHOHEUDWHV´ the misreadings and rewritings for the insights they give us into the mechanisms of the tale. Second, by analysing the episode as a weighty lesson in domestic politics, showing the fatal mistakes that can build up to regicide, the essay also aims at re-introducing an awareness of the contents of the fables as a very effective and unusual mirror for princes. Keywords: Kalila-Dimna; fables; Pancatantra; rewritings; misreadings; regicide; mirror for princes. RÉSUMÉ Cet article propose un nouveau regard sur la question des ré-écritures et traductions G¶XQ épisode-clé du cycle des fables de Kalila et 'LPQD7RXWG¶DERUGVHSODoDQWjO¶RSSRVpGH O¶DSproche habituelle des fables, qui consiste à en apprécier les différentes versions pour leur ressemblance avec le texte-source, cet article, au contraire, « célèbre » les variantes introduites par les ré-écritures de la fable au cours des siècles. Ces variantes nous donnent des informations quant à la compréhension du contenu de la fable. Ensuite, cet article analyse la fable en tant que leçon de politique domestique, car elle indique les erreurs fatales qui peuvent mener au régicide. -

The Arabian Nights in British Romantic Children's Literature Kristyn Nicole Coppinger

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 The Arabian Nights in British Romantic Children's Literature Kristyn Nicole Coppinger Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] The Florida State University College of Arts and Sciences The Arabian Nights in British Romantic Children’s Literature By Kristyn Nicole Coppinger A Thesis submitted to the Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Kristyn N. Coppinger defended on Wednesday, April 26, 2006. ___________________________________ Eric Walker Professor Directing Thesis ___________________________________ Dennis Moore Committee Member ___________________________________ James O’Rourke Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to my major professor, Eric Walker, for all of his help in completing this thesis. Thanks also to my friends and family for all their encouragement. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract v INTRODUCTION 1 1. CHILDREN’S LITERATURE 3 2. THE ARABIAN NIGHTS 8 3. READINGS 16 Sarah Fielding’s The Governess 16 The Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor 18 Richard Johnson’s The Oriental Moralist 20 John Aikin’s Evenings at Home 22 Maria Edgeworth’s “Murad the Unlucky” 27 The History of Abou Casem, and His Two Remarkable Slippers 32 Charles and Mary Lamb’s Mrs.Leicester’s School 33 CONCLUSION 41 BIBLIOGRAPHY 42 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 46 iv ABSTRACT Children’s literature emerged as a new genre in the eighteenth century. -

Les Cinq Livres De La Sagesse. Pancatantra

Mep Pancatantra poche-c10,5 14/02/12 12:09 Page 2 Mep Pancatantra poche-c10,5 14/02/12 12:09 Page 3 Les Cinq Livres de la sagesse PAÑCATANTRA Traduit du sanskrit et présenté par Alain Porte Mep Pancatantra poche-c10,5 14/02/12 12:28 Page 4 © 2000, Editions Philippe Picquier pour la traduction en langue française et l’ensemble de l’appareil critique © 2012, Editions Philippe Picquier pour l’édition de poche Mas de Vert B.P. 20150 13631 Arles cedex www.editions-picquier.fr En couverture : © Karen Knorr courtesy of Filles du Calvaire Gallery, France Conception graphique : Picquier & Protière Mise en page : Ad litteram, www.adlitteram-corrections.fr ISBN : 978-2-8097-0337-5 ISSN : 1251-6007 Mep Pancatantra poche-c10,5 14/02/12 12:09 Page 5 SOMMAIRE Avant-propos .................................................................. 13 Préface ............................................................................... 17 Avertissement ................................................................. 33 PAÑCATANTRA Prologue ............................................................................ 37 LIVRE I La désunion des amis ou le Taureau, le Lion et les deux Chacals Le Taureau, le Lion et les deux Chacals ............ 45 Le Singe et le Poteau .................................................. 52 (raconté par Karataka, le chacal) Le Chacal et le Tambour ........................................... 72 (raconté par Damanaka, le chacal) Le Marchand, le Balayeur et le Roi ..................... 82 (raconté par Damanaka, le chacal) 5 Mep Pancatantra poche-c10,5 14/02/12 12:09 Page 6 LES CINQ LIVRES DE LA SAGESSE Histoire de Devasharma ............................................ 93 (racontée par Damanaka, le chacal, compre - nant : Les deux Béliers et le Chacal & Le Tisserand, le Barbier et leurs Femmes ) Le Tisserand qui se fit passer pour Vishnu ...... 110 (raconté par Damanaka, le chacal) Les deux Corbeaux, le Chacal et le Serpent ... -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 07 September 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Newman, Daniel (2018) 'Wandering nights : Shahrazd's mutations.', in The life of texts : evidence in textual production, transmission and reception.. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 62-92. Further information on publisher's website: https://www.bloomsbury.com/9781350039056 Publisher's copyright statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Bloomsbury Academic in The life of texts: evidence in textual production, transmission and reception on 01 Nov 2018, available online:http://www.bloomsbury.com/9781350039056. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Wandering Nights: Shahrazād’s Mutations In 2010, a group calling themselves ‘Lawyers Without Shackles’ (Muḥāmūn bilā quyūd) filed a complaint with Egypt’s Prosecutor-general when a new edition of the Arabian Nights, known in Arabic as Alf Layla wa Layla (‘Thousand and One Nights’), was published, due to its allegedly ‘obscene’ content. -

Burcuatalas2010.Pdf (2.802Mb)

T.C. EGE ÜN0VERS0TES0 SOSYAL B0L0MLER ENST0TÜSÜ Türk Dili ve Edebiyatı Anabilim Dalı Eski Türk Edebiyatı Bilim Dalı TÛTÎ-NÂME (MET0N VE 0NCELEME) (88a– 177b) YÜKSEK L0SANS TEZ0 Hazırlayan: Burcu ATALAS DANI1MAN: Yard. Doç Dr. 1. Fatih ÜLKEN 0ZM0R- 2010 Ege Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlü/üne sundu/um “Tûtî-nâme Metin ve 0nceleme (88a-177b)” adlı yüksek lisans tezinin tarafımdan bilimsel, ahlak ve normlara uygun bir 2ekilde hazırlandı/ını, tezimde yararlandı/ım kaynakları bibliyografyada ve dipnotlarda gösterdi/imi onurumla do/rularım. Burcu ATALAS TUTANAK Ege Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Yönetim Kurulu’nun ..../........./......... tarih ve ........... sayılı kararı ile olu2turulan jüri ............................................................... anabilim dalı yüksek lisans ö/rencisi ........ ............. ................................................’nın a2a/ıda (Türkçe / 0ngilizce) belirtilen tezini incelemi2 ve adayı ...../........./......... günü saat ............’da .................... süren tez savunmasına almı2tır. Sınav sonunda adayın tez savunmasını ve jüri üyeleri tarafından tezi ile ilgili kendisine yöneltilen sorulara verdi/i cevapları de/erlendirerek tezin ba2arılı/ba2arısız/düzeltilmesi gerekli oldu/una oybirli/iyle / oyçoklu/uyla karar vermi2tir. BA1KAN Ba2arılı Ba2arısız Düzeltme (Üç ay süreli) ÜYE ÜYE Ba2arılı Ba2arılı Ba2arısız Ba2arısız Düzeltme (Üç ay süreli) Düzeltme (Üç ay süreli) Tezin Türkçe Ba2lı/ı : Tezin 0ngilizce Ba2lı/ı : 0Ç0NDEK0LER Önsöz .............................................................................................................................