Download Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Associate Enablement Perspectives

CONFIDENTIAL 1H2020 Associate Enablement Perspectives DISCLAIMER: ComCap LLC make no representation or warranty, express or implied, in relation to the fairness, accuracy, correctness, completeness, or reliability of the information, opinions, or conclusions contained herein. ComCap LLC accepts no liability for any use of these materials. The materials are not intended to be relied upon as advice outside of a paid, approved use and they should not be considered a guarantee of any specific result. Each recipient should consult his or her own accounting, tax, financial, and other professional advisors when considering the scenarios and information provided. An introduction to ComCap ▪ ComCap is a premier boutique investment bank focused on the intersection of commerce and capital, with key focus on B2B SaaS, B2C e-commerce, payments, mobile commerce, marketplaces and B2B services for retail technologies (IT and marketing services, in-store, fulfillment, logistics, call center, analytics, personalization, location intelligence) ▪ Headquartered in San Francisco with European coverage from London & Moscow, and LATAM coverage from Sao Paulo. Our firm works with mid-cap public companies on buyside initiatives and public and private growth companies on financing and strategic M&A ▪ In addition to being the only boutique focused on disruptive commerce models, we differentiate by: ‒ Bringing bulge bracket techniques to emerging models; ‒ A strong and uncommon buyside/strategy practice; ‒ Deep understanding of industry drivers and synergy analyses; -

View Whitepaper

INFRAREPORT Top M&A Trends in Infrastructure Software EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1 EVOLUTION OF CLOUD INFRASTRUCTURE 7 1.1 Size of the Prize 7 1.2 The Evolution of the Infrastructure (Public) Cloud Market and Technology 7 1.2.1 Original 2006 Public Cloud - Hardware as a Service 8 1.2.2 2016 - 2010 - Platform as a Service 9 1.2.3 2016 - 2019 - Containers as a Service 10 1.2.4 Container Orchestration 11 1.2.5 Standardization of Container Orchestration 11 1.2.6 Hybrid Cloud & Multi-Cloud 12 1.2.7 Edge Computing and 5G 12 1.2.8 APIs, Cloud Components and AI 13 1.2.9 Service Mesh 14 1.2.10 Serverless 15 1.2.11 Zero Code 15 1.2.12 Cloud as a Service 16 2 STATE OF THE MARKET 18 2.1 Investment Trend Summary -Summary of Funding Activity in Cloud Infrastructure 18 3 MARKET FOCUS – TRENDS & COMPANIES 20 3.1 Cloud Providers Provide Enhanced Security, Including AI/ML and Zero Trust Security 20 3.2 Cloud Management and Cost Containment Becomes a Challenge for Customers 21 3.3 The Container Market is Just Starting to Heat Up 23 3.4 Kubernetes 24 3.5 APIs Have Become the Dominant Information Sharing Paradigm 27 3.6 DevOps is the Answer to Increasing Competition From Emerging Digital Disruptors. 30 3.7 Serverless 32 3.8 Zero Code 38 3.9 Hybrid, Multi and Edge Clouds 43 4 LARGE PUBLIC/PRIVATE ACQUIRERS 57 4.1 Amazon Web Services | Private Company Profile 57 4.2 Cloudera (NYS: CLDR) | Public Company Profile 59 4.3 Hortonworks | Private Company Profile 61 Infrastructure Software Report l Woodside Capital Partners l Confidential l October 2020 Page | 2 INFRAREPORT -

April 2020 Monthly Update

Sustainable Technology and Infrastructure Monthly Market Update // April 2020 Performance of Key Market Indices(1) 60.0% 40.0% 20.0% 16.4% 9.8% 0.0% (1.1%) (20.0%) (8.5%) (40.0%) Apr-19 Jun-19 Aug-19 Oct-19 Dec-19 Feb-20 Apr-20 NASDAQ Clean Edge Green Energy Dow Jones Industrial Average NASDAQ Composite S&P 500 Index Performance(1) April Ending Versus April YTD CY 2019 52 Wk High 52 Wk Low Dow Jones Industrial Average 11.1% (14.7%) 22.3% (17.6%) 30.9% NASDAQ Composite 15.4% (0.9%) 35.2% (9.4%) 29.6% S&P 500 12.7% (9.9%) 28.9% (14.0%) 30.2% NASDAQ Clean Edge Green Energy 21.8% (1.6%) 40.7% (21.0%) 44.6% Notable Recent Transactions & Capital Raises Target Acquirer Transaction Description Lime, a provider of micro-mobility products, acquired the IP and Boosted Lime assets of Boosted, a provider of electric skateboards, for an undisclosed sum First State Investments, an Australia-based infrastructure investor, M&A First State MVV Energie acquired a 45.1% interest in MVV Energie, a Germany-based Transactions Investments energy provider, for €753mm ($816mm) Nippon Nippon Suisan (Europe) and Marubeni jointly acquired a 67% Danish Suisan interest in Danish Salmon, an operator of a salmon farming Salmon business that specializes in the implementation of a recirculating Marubeni aquaculture system, for an undisclosed sum Company Transaction Description Kurly, a Korea-based developer of an online grocery delivery platform, raised a Kurly $150mm round led by Sequoia Capital, Hillhouse Capital and DST Global Capital Nio, a China-based electric vehicle manufacturer, raised a $1bn round led by Hefei Raises Nio Construction Investment Holding and New Technology Industrial Investment Co. -

2020 Philadelphia Venture Report

2020 PHILADELPHIA VENTURE REPORT Data provided by WE HELP BREAKTHROUGH IDEAS ACTUALLY BREAK THROUGH. We believe in the risk takers, the game-changers and the disruptors—those who committed to leveraging innovation to make the world a better place. Bridge Bank, founded in 2001 in Silicon Valley, serves small-market and middle-market businesses across many industries, as well as emerging technology and life sciences companies and the private equity community. Geared to serving both venture-backed and non-venture-backed companies across all stages of growth, Bridge Bank offers a broad scope of financial solutions including growth capital, equipment and working capital credit facilities, venture debt, treasury management, asset-based lending, SBA and commercial real estate loans, ESOP finance and full line of international products and services. To learn more about us, visit info.bridgebank.com/tech-innovation. Matt Klinger Brian McCabe Senior Director, Technology Banking Senior Director, Technology Banking [email protected] [email protected] (703) 547-8198 (703) 345-9307 Bridge Bank, a division of Western Alliance Bank. Member FDIC. *All offers of credit are subject to approval. Introduction 2020 was a watershed moment on so many fronts. The COVID-19 pandemic will forever change how we live, work, and interact. The killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and countless others have brought focus and urgency to attacking racism, racial injustice, and the resulting inequities in our society. Philadelphia has always been a city fueled by passion and determination to challenge the status quo, think differently, invent, and push forward together. This report showcases the fruits of that passion in the form of capital raised to fuel innovation. -

VC Daily: Cargill Joins Probiotics Company's Fundraising; 500 Startups Hosts Virtual Pitches; Edison Eyes Fund Good Day

FEBRUARY 08, 2021 VC Daily: Cargill Joins Probiotics Company's Fundraising; 500 Startups Hosts Virtual Pitches; Edison Eyes Fund Good day. Last week, startup guts with a strain of bacteria called B. eliminated commissions, making buying a accelerator 500 Startups held its second infantis, which protects newborns and share of stock about as easy as posting a virtual demo day since the pandemic nourishes a healthy gut. Because of photo on Instagram. It worked. During upended the event. Roughly two dozen factors such as rising antibiotic use in the pandemic, throngs of amateur startups, which joined the accelerator recent decades, many mothers don't have investors—homebound, bored and flush earlier this year, made rapid-fire two B. infantis to pass on their children, with stimulus checks—opened Robinhood minute pitches to investors who tuned according to Evolve. accounts to experience the market's in. * Cargill plans to help Evolve thrills. By the end of December, the firm explore new applications for its probiotic had amassed about 20 million users, Pawsh, a mobile pet-grooming technology, including human and animal according to people close to it, and weeks service, pitched investors on its uses. later its app hit the top of download "groomer-first business model" which 65% charts. It should have been a moment to Chief Executive Officer Karthik Roughly the share of lithium-ion celebrate. Instead, a recent Thursday Naralasetty said is experiencing 30% batteries that come from China. began with a panicked, predawn phone revenue growth. Edison Partners Eyes $425 Million call informing Mr. Tenev that Robinhood for Latest Fund needed to come up with billions of dollars Drover.ai pitched a hardware Growth-equity firm Edison if it wanted to open for business in a few device that scooter-sharing fleets could Partners is preparing to launch its latest hours. -

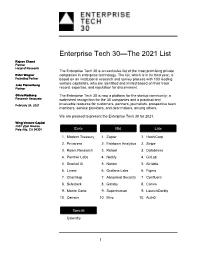

Enterprise Tech 30—The 2021 List

Enterprise Tech 30—The 2021 List Rajeev Chand Partner Head of Research The Enterprise Tech 30 is an exclusive list of the most promising private Peter Wagner companies in enterprise technology. The list, which is in its third year, is Founding Partner based on an institutional research and survey process with 103 leading venture capitalists, who are identified and invited based on their track Jake Flomenberg Partner record, expertise, and reputation for discernment. Olivia Rodberg The Enterprise Tech 30 is now a platform for the startup community: a Research Associate watershed recognition for the 30 companies and a practical and February 24, 2021 invaluable resource for customers, partners, journalists, prospective team members, service providers, and deal makers, among others. We are pleased to present the Enterprise Tech 30 for 2021. Wing Venture Capital 480 Lytton Avenue Palo Alto, CA 94301 Early Mid Late 1. Modern Treasury 1. Zapier 1. HashiCorp 2. Privacera 2. Fishtown Analytics 2. Stripe 3. Roam Research 3. Retool 3. Databricks 4. Panther Labs 4. Netlify 4. GitLab 5. Snorkel AI 5. Notion 5. Airtable 6. Linear 6. Grafana Labs 6. Figma 7. ChartHop 7. Abnormal Security 7. Confluent 8. Substack 8. Gatsby 8. Canva 9. Monte Carlo 9. Superhuman 9. LaunchDarkly 10. Census 10. Miro 10. Auth0 Special Calendly 1 2021 The Curious Case of Calendly This year’s Enterprise Tech 30 has 31 companies rather than 30 due to the “curious case” of Calendly. Calendly, a meeting scheduling company, was categorized as Early-Stage when the ET30 voting process started on January 11 as the company had raised $550,000. -

Comcap's Guide to Commerce & Payments at Money

CONFIDENTIAL Photo by visitlasvegas.com October 2018 ComCap’s Guide to Commerce & Payments at Money 20/20 DISCLAIMER: ComCap LLC make no representation or warranty, express or implied, in relation to the fairness, accuracy, correctness, completeness, or reliability of the information, opinions, or conclusions contained herein. ComCap LLC accepts no liability for any use of these materials. The materials are not intended to be relied upon as advice outside of a paid, approved use and they should not be considered a guarantee of any specific result. Each recipient should consult his or her own accounting, tax, financial, and other professional advisors when considering the scenarios and information provided. CONFIDENTIAL An introduction to ComCap ▪ Money 20/20 provides an unprecedented platform to network with CEOs and executives of early stage companies, payment companies, fintech disruptors and financial service providers. ▪ ComCap is a premier boutique investment bank focused on the intersection of commerce and capital, with key focus on B2B SaaS, B2C E-commerce, payments, mobile commerce, marketplaces and B2B services for retail technologies (IT and marketing services, in-store, fulfillment, logistics, call center, analytics, personalization) ▪ Headquartered in San Francisco with Australasia coverage from Singapore, European coverage from London & Moscow, and LATAM coverage from Sao Paolo. Our firm works with mid-cap public companies on buyside initiatives and public and private growth companies on financing and strategic M&A ▪ In addition -

Global Venture Capital Funded Startups December 2017

BUSINESS RESEARCH & CORPORATE INFORMATION SERVICES Global Venture Capital Funded Startups December 2017 **The information in this report is aggregated by the team at AM Research from various sources across the web. **The team at AMR tracks the global startup funding ecosystem closely and profiles thousands of VC firms and their portfolio startups. AM Research Services is a provider of desk research services to high growth startups and large global corporations. Kindly visit our website www.amresearch.in and contact us at [email protected] for any desk research requests, samples and quote. BUSINESS RESEARCH & CORPORATE INFORMATION SERVICES 10 Most Active Venture Capital Firms in December’ 2017 AM Research Services is a provider of desk research services to high growth startups and large global corporations. Kindly visit our website www.amresearch.in and contact us at [email protected] for any desk research requests, samples and quote. BUSINESS RESEARCH & CORPORATE INFORMATION SERVICES Breakout By Funding Rounds AM Research Services is a provider of desk research services to high growth startups and large global corporations. Kindly visit our website www.amresearch.in and contact us at [email protected] for any desk research requests, samples and quote. BUSINESS RESEARCH & CORPORATE INFORMATION SERVICES Series - A Funded Companies Amount Company Country Description Investors Raised Guardian Guardian optical Technologies is an Maniv Mobility Optical innovative israeli startup developing an $5.1 million Israel Mirai Creation Fund Technologies advanced 3D sensor. Noodle Noodle Partners helps colleges and United Owl Ventures $14 million Partners Inc universities create and manage first-rate States online and hybrid programs. Mayfield Earny United Earny, santa Monica, California-based a Comcast Ventures $9 million States personal finance service company. -

Secondaries Market Overview Investors Are Facing Significant Headwinds Across Various Asset Classes

Secondaries Market Overview Investors are facing significant headwinds across various asset classes Interest rates are at unprecedented low levels, leading to major risks for fixed income. Equity markets are trading well above long term averages exposing investors to downside risk. Market volatility has increased in the last few months implying pressure on equity returns ahead. A glut of capital into PE has led to increase in entry prices thus diminishing the returns for the asset class. Finally, the lengthening of time to exit for startups has caused traditional VC funds to extend the length of their fund life and returns aren’t capturing the illiquidity premium necessary to justify the investment. Faced with the dual challenges on both the asset and liability fronts, we believe that secondaries present an excellent risk-adjusted return profile, exhibiting defensive attributes while still providing attractive long-term returns. 1 History and growth of the Secondary Market The secondary market dates back to the Global Secondary Transaction Volume 1980s, when a handful of firms started $billions selectively purchasing interests in buyout and VC funds. It took the market two decades to develop from a niche market to a functional and active market place. We believe the strong growth since 2005 is a result of several factors affecting supply and demand. On the supply side, strong funding environments for primary funds from 2005 to 2008 followed by the financial crisis led to greater acceptance of secondaries as a tool for managers to meet liquidity and regulatory needs. The availability of well performing yet discounted assets led to a growing demand that fueled transaction volume. -

Comcap Evolution of Digital Brands Report

DIGITALLY NATIVE Summer 2020 ComCap Evolution of Digital Brands Report DISCLAIMER: ComCap LLC make no representation or warranty, express or implied, in relation to the fairness, accuracy, correctness, completeness, or reliability of the information, opinions, or conclusions contained herein. ComCap LLC accepts no liability for any use of these materials. The materials are not intended to be relied upon as advice outside of a paid, approved use and they should not be considered a guarantee of any specific result. Each recipient should consult his or her own accounting, tax, financial, and other professional advisors when considering the scenarios and information provided. And yes, we are probably representing1 and/or soliciting business from everyone in this report. Foreword to ComCap’s DNVB Evolution report . Since the publishing of our original DNVB report we’ve had the opportunity to work with brands, marketplaces and consolidators and speak with scores of venture capital, private equity firms and major brands and retailers about their intentions for the space . As a firm focused on M&A and private placement transactions, we’ve been keenly interesting in seeing disruptive companies come to the market . Ultimately we’ve been disappointed in the sub-sector’s evolution, our overall take is that most DNVB’s are single-product companies and lack the scalability or leverage needed to capture significant share or to truly disrupt large incumbents . Most founding teams excel at either product or marketing in a single channel – very few teams are able to raise the capital needed to build out a team that is effective across multiple products and multiple modes of customer acquisition . -

Silicon Valley London Woodside Capital Partners (WCP)

Silicon Valley London Woodside Capital Partners (WCP) proudly releases the inaugural healthcare report “State of Digital Health”. In 2016, healthcare cost in the US was $3.3 Trillion – 17.9% of GDP, passing $10,000 per capita mark for the first time ever. According to CMS, by 2026, the figure is projected to grow to $5.7 Trillion – 19.8% of GDP. The answer to curbing and reversing the trend with respect to healthcare costs lies in large part to the movement towards Digital Health, or ‘Health Tech’. The proliferation of devices and applications across the healthcare spectrum has led to a data tsunami – the “what”. Machine Learning, Artificial Intelligence and overall Big Data analytics are leading to real-time actionable insights – the “so what”. We have entered the realm of the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT), with ubiquitous connectivity and measurement of everything from our vitals and nutrition to physical activity and medical compliance. We are just starting to leverage that data in a meaningful way and seeing early impact on health and well-being. In 2017, venture investments in Digital Health startups exceeded $6 Billion for the first time, and the trend seems to be accelerating with $1.6 Billion invested in Q1, 2018. The juxtaposition of rising healthcare costs and increased Digital Health investments is not all that surprising. Advances in underlying real-time analytics and potential of leading edge innovations around genomics are turning the perceived fiction of personalized medicine into a real possibility. Foundational disruptions such as Blockchain, while relatively nascent, are creating excitement (and some anxiety) around secure, immutable data sharing across silos – with healthcare as the ideal use case. -

Biotechnology Startups Research Report

GLOBAL BUSINESS CONFIDENCE REPORT 4th Qtr. 2019 B IOTECH NOLOGY STARTUPS RESEARCH REPORT 4th Quarter 2019 www.tradecouncil.org www.qibcertification.org International Trade Council www.tradecouncil.org www.goglobalawards.org Page 1 MARKET OVERVIEW REPORT FOR ENTERPRISE ESTONIA Table of Contents Overview ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Industry Definition .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Sectoral Definitions ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Main Activities .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Associated Industries ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Industry at a Glance ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Industry Overview ..........................................................................................................................................................................................