PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mongolian Big Dipper Sūtra

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 29 Number 1 2006 (2008) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. It welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. EDITORIAL BOARD JIABS is published twice yearly, in the summer and winter. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: Joint Editors [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, BUSWELL Robert in two different formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- CHEN Jinhua Document-Format (created e.g. by Open COLLINS Steven Office). COX Collet GÓMEZ Luis O. Address books for review to: HARRISON Paul JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur - und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- VON HINÜBER Oskar Strasse 8-10, AT-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA JACKSON Roger JAINI Padmanabh S. Address subscription orders and dues, KATSURA Shōryū changes of address, and UO business correspondence K Li-ying (including advertising orders) to: LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer MACDONALD Alexander Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Anthropole SEYFORT RUEGG David University of Lausanne CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland SHARF Robert email: [email protected] STEINKELLNER Ernst Web: www.iabsinfo.net TILLEMANS Tom Fax: +41 21 692 30 45 ZÜRCHER Erik Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

APA NEWSLETTER on Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies SPRING 2020 VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 FROM THE GUEST EDITOR Ben Hammer The Timeliness of Translating Chinese Philosophy: An Introduction to the APA Newsletter Special Issue on Translating Chinese Philosophy ARTICLES Roger T. Ames Preparing a New Sourcebook in Classical Confucian Philosophy Tian Chenshan The Impossibility of Literal Translation of Chinese Philosophical Texts into English Dimitra Amarantidou, Daniel Sarafinas, and Paul J. D’Ambrosio Translating Today’s Chinese Masters Edward L. Shaughnessy Three Thoughts on Translating Classical Chinese Philosophical Texts Carl Gene Fordham Introducing Premodern Text Translation: A New Field at the Crossroads of Sinology and Translation Studies SUBMISSION GUIDELINES AND INFORMATION VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 SPRING 2020 © 2020 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies BEN HAMMER, GUEST EDITOR VOLUME 19 | NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2020 Since most of us reading this newsletter have at least a FROM THE GUEST EDITOR vague idea of what Western philosophy is, we must understand that to then learn Chinese philosophy is truly The Timeliness of Translating Chinese to reinvent the wheel. It is necessary to start from the most basic notions of what philosophy is to be able to understand Philosophy: An Introduction to the APA what Chinese philosophy is. Newsletter Special Issue on Translating In the West, religion is religion and philosophy is Chinese Philosophy philosophy. In China, this line does not exist. For China and its close East Asian neighbors, Confucianism has guided Ben Hammer the social and spiritual lives of people for thousands of EDITOR, JOURNAL OF CHINESE HUMANITIES years in the same way the Judeo-Christian tradition has [email protected] guided people in the West. -

The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan

THE HISTORY OF GYALTHANG UNDER CHINESE RULE: MEMORY, IDENTITY, AND CONTESTED CONTROL IN A TIBETAN REGION OF NORTHWEST YUNNAN Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Michael Tsin Michelle T. King Ralph A. Litzinger W. Miles Fletcher Donald M. Reid © 2016 Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii! ! ABSTRACT Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen: The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan (Under the direction of Michael Tsin) This dissertation analyzes how the Chinese Communist Party attempted to politically, economically, and culturally integrate Gyalthang (Zhongdian/Shangri-la), a predominately ethnically Tibetan county in Yunnan Province, into the People’s Republic of China. Drawing from county and prefectural gazetteers, unpublished Party histories of the area, and interviews conducted with Gyalthang residents, this study argues that Tibetans participated in Communist Party campaigns in Gyalthang in the 1950s and 1960s for a variety of ideological, social, and personal reasons. The ways that Tibetans responded to revolutionary activists’ calls for political action shed light on the difficult decisions they made under particularly complex and coercive conditions. Political calculations, revolutionary ideology, youthful enthusiasm, fear, and mob mentality all played roles in motivating Tibetan participants in Mao-era campaigns. The diversity of these Tibetan experiences and the extent of local involvement in state-sponsored attacks on religious leaders and institutions in Gyalthang during the Cultural Revolution have been largely left out of the historiographical record. -

Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Gregory Adam Scott All Rights Reserved This work may be used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. For more information about that license, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. For other uses, please contact the author. ABSTRACT Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China 經典佛化: 民國初期佛教出版文化 Gregory Adam Scott 史瑞戈 In this dissertation I argue that print culture acted as a catalyst for change among Buddhists in modern China. Through examining major publication institutions, publishing projects, and their managers and contributors from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s, I show that the expansion of the scope and variety of printed works, as well as new the social structures surrounding publishing, substantially impacted the activity of Chinese Buddhists. In doing so I hope to contribute to ongoing discussions of the ‘revival’ of Chinese Buddhism in the modern period, and demonstrate that publishing, propelled by new print technologies and new forms of social organization, was a key field of interaction and communication for religious actors during this era, one that helped make possible the introduction and adoption of new forms of religious thought and practice. 本論文的論點是出版文化在近代中國佛教人物之中,扮演了變化觸媒的角色. 通過研究從十 九世紀末到二十世紀二十年代的主要的出版機構, 種類, 及其主辦人物與提供貢獻者, 論文 說明佛教印刷的多元化 以及範圍的大量擴展, 再加上跟出版有關的社會結構, 對中國佛教 人物的活動都發生了顯著的影響. 此研究顯示在被新印刷技術與新形式的社會結構的推進 下的出版事業, 為該時代的宗教人物展開一種新的相互連結與構通的場域, 因而使新的宗教 思想與實踐的引入成為可能. 此論文試圖對現行關於近代中國佛教的所謂'復興'的討論提出 貢獻. Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables iii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations and Conventions ix Works Cited by Abbreviation x Maps of Principle Locations xi Introduction Print Culture and Religion in Modern China 1. -

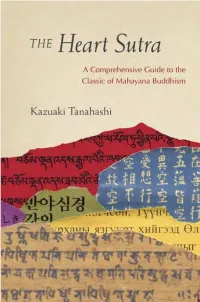

The Heart Sutra in Its Primarily Chinese and Japanese Contexts Covers a Wide Range of Approaches to This Most Famous of All Mahayana Sutras

“Tanahashi’s book on the Heart Sutra in its primarily Chinese and Japanese contexts covers a wide range of approaches to this most famous of all mahayana sutras. It brings the sutra to life through shedding light on it from many different angles, through presenting its historical background and traditional commentaries, evaluating modern scholarship, adapting the text to a contemporary readership, exploring its relationship to Western science, and relating personal anecdotes. The rich- ness of the Heart Sutra and the many ways in which it can be understood and contemplated are further highlighted by his comparison of its versions in the major Asian languages in which it has been transmitted, as well as in a number of English translations. Highly recommended for all who wish to explore the profundity of this text in all its facets.” — Karl Brunnhölzl, author of The Heart Attack Sutra: A New Commentary on the Heart Sutra “A masterwork of loving and meticulous scholarship, Kaz Tanahashi’s Heart Sutra is a living, breathing, deeply personal celebration of a beloved text, which all readers—Buddhists and non-Buddhists, newcomers to the teaching and seasoned scholars alike—will cherish throughout time.” — Ruth Ozeki, author of A Tale for the Time Being Heart Sutra_3rd pass_revIndex.indd 1 10/22/14 1:14 PM Also by Kazuaki Tanahashi Beyond Thinking: A Guide to Zen Meditation Enlightenment Unfolds: The Essential Teachings of Zen Master Dogen The Essential Dogen (with Peter Levitt) Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen’s Shobo Genzo Heart Sutra_3rd pass_revIndex.indd 2 10/22/14 1:14 PM THE Heart Sutra A Comprehensive Guide to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism Kazuaki Tanahashi Shambhala Boston & London 2014 Heart Sutra_3rd pass_revIndex.indd 3 10/22/14 1:14 PM Shambhala Publications, Inc. -

Catalogo N°36

1 Indice Tibet e paesi Himalayani Pag. 3 Arte Storia, letteratura, etnologia Viaggi e varie India ” 37 Arte, Storia, letteratura, etnologia, letteratura Viaggi e varie Letteratura Urdu ” 69 Cacciatori di piante ” 91 Himalaya: montagne divine ” 98 SEA Cina Giappone ” 106 Arte, Viaggi e varie Africa ” 121 A short selection 2 Parma inverno 2014 Un anno dopo è difficile raccontare del come gli eventi si frappongano alla tentazione di una vita routinaria e alle scadenze che come tacche sul bastone della vita tendono ad avvitarsi in un processo senza fine. Libri, cataloghi, viaggi:: talvolta incontri di persone nuove, o il ritrovarsi dopo mplto tempo con un denso mantello di ricordi, di luoghi, di anni fuggiti e la sensazione di avere perso un pezzo di mondo o di averne vissuto uno in un altro luogo. Il 2013 è stato un anno difficile da molti punti di vista e dobbiamo ricominciare a programmare una proposta che mantenga il contatto con gli amici che aspettano il catalogo e che fa piacere accontentare. Ci sono mancate molte persone care, altre abbiamo dovuto assistere in momenti difficili, è mancata la concentrazione necessaria, a volte la voglia di lottare per tenere viva la luce sopre l’insegna e aggiornata la bibliografia. Scrivo queste righe in una città deserta nel caldo ferragostano, con molte serrande abbassate e la sensazione che molte non riapriranno neppure a settembre, ma mi conforta il muro dei libri con i titoli in oro e le belle storie che gli autori continuano a raccontare senza fine nella pazienza dei secoli: Barrow e la Conchincina, Rennell e la sua Memoir on a map of Hindoostan, Elphinstone e il suo Accont on the Kingdom of Kaubul,, Jaquemont e il suo peregrinare in India da modesto stipendiato del Jardin des plantes di Parigi ma ricco delle raccomandazioni dei parenti nobili e della simpatia dei coloni inglesi verso questo giovene ospite che riusciva a conquistare la simpatia di Ranjit Singh, il satrapo del Panjab e padrone del Kashmir. -

A Study of Zongmi's Chan Buddhist Hermeneutical Diagram Indicating

2017 3rd Annual International Conference on Modern Education and Social Science (MESS 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-450-9 A Study of Zongmi’s Chan Buddhist Hermeneutical Diagram Indicating the Mind of Sentient Beings Qing MING Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, Yunnan, China [email protected] Keywords: Chan Buddhism, Zongmi, Ãlayavijñāna, Reality, Delusion. Abstract: Zongmi was a famous scholarly Chan Buddhist monk in Chinese Buddhism, he was deeply interested in both the practical and doctrinal aspects of Buddhism. An important part of his thought is to mergeed Chan Buddhism with the philosophy of The Book of Change, this thought played a groundbreaking role in the harmonization of the major schools of Chinese culture. Thus, this paper taken Zongmi’s Chan Buddhist hermeneutical diagram interpreting the mind of sentient beings as its objects of research, in the paper, the Zongmi Chan diagrams and pictorial schemes will be approached by focusing on three aspects: 1) the life of Zongmi and his works, 2) Chan hermeneutical diagrams that attempt to represent the minds’ functions of sentient beings, and 3) the relationship between mind, the Supreme Ultimate and ālayavijñāna. Introduction Zongmi (780-841) was a Tang dynasty famous Buddhist scholar-monk, the fifth patriarch of the Chinese Buddhist Huayan school and a patriarch of Heze lineage of Southern Sudden-enlightenment Chan Buddhism; he was deeply influenced by both Chan Buddhism and Huayan philosophy. He wrote a number of works on the contemporary situation of Buddhism in Tang China, his work had an enduring influence on the adaptation of Indian Buddhism to the philosophy of traditional Chinese culture. -

The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World

The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World • Lynn A. Struve University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu © 2019 University of Hawai‘i Press This content is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that it may be freely downloaded and shared in digital format for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. Commercial uses and the publication of any derivative works require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. The open-access version of this book was made possible in part by an award from the James P. Geiss and Margaret Y. Hsu Foundation. Cover art: Woodblock illustration by Chen Hongshou from the 1639 edition of Story of the Western Wing. Student Zhang lies asleep in an inn, reclining against a bed frame. His anxious dream of Oriole in the wilds, being confronted by a military commander, completely fills the balloon to the right. In memory of Professor Liu Wenying (1939–2005), an open-minded, visionary scholar and open-hearted, generous man Contents Acknowledgments • ix Introduction • 1 Chapter 1 Continuities in the Dream Lives of Ming Intellectuals • 15 Chapter 2 Sources of Special Dream Salience in Late Ming • 81 Chapter 3 Crisis Dreaming • 165 Chapter 4 Dream-Coping in the Aftermath • 199 Epilogue: Beyond the Arc • 243 Works Cited • 259 Glossary-Index • 305 vii Acknowledgments I AM MOST GRATEFUL, as ever, to Diana Wenling Liu, head of the East Asian Col- lection at Indiana University, who, over many years, has never failed to cheerfully, courteously, and diligently respond to my innumerable requests for problematic materials, puzzlements over illegible or unfindable characters, frustrations with dig- ital databases, communications with publishers and repositories in China, etcetera ad infinitum. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 13 Fall 2011 SPECIAL SECTION: Recent Research on Esoteric Buddhism TITLE iii Pacific World is an annual journal in English devoted to the dissemination of his- torical, textual, critical, and interpretive articles on Buddhism generally and Shinshu Buddhism particularly to both academic and lay readerships. The journal is distributed free of charge. Articles for consideration by the Pacific World are welcomed and are to be submitted in English and addressed to the Editor, Pacific World, 2140 Durant Ave., Berkeley, CA 94704-1589, USA. Acknowledgment: This annual publication is made possible by the donation of BDK America of Berkeley, California. Guidelines for Authors: Manuscripts (approximately twenty standard pages) should be typed double-spaced with 1-inch margins. Notes are to be endnotes with full biblio- graphic information in the note first mentioning a work, i.e., no separate bibliography. See The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition), University of Chicago Press, §16.3 ff. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of all quotations and for supplying complete references. Please e-mail electronic version in both formatted and plain text, if possible. Manuscripts should be submitted by February 1st. Foreign words should be underlined and marked with proper diacriticals, except for the following: bodhisattva, buddha/Buddha, karma, nirvana, samsara, sangha, yoga. Romanized Chinese follows Pinyin system (except in special cases); romanized Japanese, the modified Hepburn system. Japanese/Chinese names are given surname first, omit- ting honorifics. Ideographs preferably should be restricted to notes. Editorial Committee reserves the right to standardize use of or omit diacriticals. -

Disszertáció Tóth Erzsébet Mongol–Tibeti Nyelvi Kölcsönhatások 2008

+ DOKTORI (PHD) DISSZERTÁCIÓ TÓTH ERZSÉBET MONGOL–TIBETI NYELVI KÖLCSÖNHATÁSOK 2008 TothErzsebet_PhD-dissz.doc i 2008.10.02. + Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem Bölcsészettudományi Kar Nyelvtudományi Doktori Iskola Mongol Nyelvészeti Program Vezetęje: Vezetęje: PROF. DR. BAĔCZEROWSKI JANUSZ DR. BIRTALAN ÁGNES egyetemi tanár habil. egyetemi docens DOKTORI (PHD) DISSZERTÁCIÓ TÓTH ERZSÉBET MONGOL–TIBETI NYELVI KÖLCSÖNHATÁSOK Témavezetę: DR. SÁRKÖZI ALICE, kandidátus A bíráló bizottság Elnöke: PROF. DR. FODOR SÁNDOR, egyetemi tanár Titkára: DR. SZILÁGYI ZSOLT, PhD Tagja: DR. PORCIÓ TIBOR, PhD Póttagja: DR. BALCHIG KATUU, akadémiai doktor Hivatalosan felkért bírálók: PROF. DR. KARA GYÖRGY, akadémikus DR. FEHÉR JUDIT, kandidátus 2008 TothErzsebet_PhD-dissz.doc ii 2008.10.02. + Tartalom Köszönetnyilvánítás ....................................................................................................... iii 1. Bevezetés ..................................................................................................................... 1 2. A mongol–tibeti kapcsolatok történeti háttere ....................................................... 2 2.1. A mongol–tibeti politikai kapcsolatok áttekintése ................................................ 2 2.1.1. A mongol kor elętt .............................................................................................. 2 2.1.2. A mongol birodalom idején (12–14. sz.) ............................................................ 3 2.1.3. A mongol széttagoltság idején (15–17. sz.) ....................................................... -

The Mantra of the Heart Sutra in the Journey to the West

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 286 June, 2019 The Reins of Language: The Mantra of the Heart Sutra in The Journey to the West by Shuheng Zhang Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out for peer review, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

The Zen Concept Related to Language Politeness Expression in Chanoyu Ceremony

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 383 2nd International Conference on Social Science (ICSS 2019) The Zen Concept related to Language Politeness Expression in Chanoyu Ceremony Norselady Rumengan Susanti Aror Japanese Education Study Program Japanese Education Study Program Faculty of Language and Arts, UNIMA Faculty of Language and Arts, UNIMA Manado, Indonesia Manado, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] Indria Mawitjere Japanese Education Study Program Faculty of Language and Arts – UNIMA Manado, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract-Japan has many cultures, such as religious of Modesty in Chanoyu reflects the personality and ceremonies and traditional ceremonies. The ceremony knowledge of the host including life goals, ways of for drinking tea or chanoyu is one of them which is quite thinking, religion, appreciation for Chanoyu ceremonial well-known and still exists today since the 16th century. equipment and how to place art objects in the Chanoyu Tea was introduced to Japan around the 16th century by ceremony room. 5. The Maxim of Agreement, namely Zen monks. Sen no Rikyu, one of the masters of this the participants in the Chanoyu ceremony can ceremony always uses four basic principles in chanoyu, mutually foster compatibility or agreement , and be namely harmony ( wa ), respect (kei), purity (sei) and polite. 6. The Maxim of Sympathy, that the participants calm (jaku). The research method used the library in the Chanoyu ceremony can maximize sympathy method and descriptive analysis, which describes the between one party and the other. data obtained then analyzes it. The main purpose of this Keywords: chanoyu; Modesty; Speech Act research is to gain deep meaning about the concept of Zen in the Chanoyu ceremony and the politeness expression of speech acts in the Chanoyu ceremony.