Peter in Rome?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

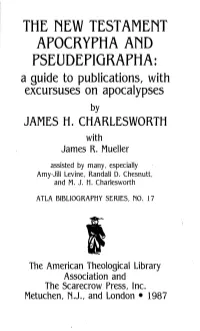

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA and PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a Guide to Publications, with Excursuses on Apocalypses by JAMES H

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA AND PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a guide to publications, with excursuses on apocalypses by JAMES H. CHARLESWORTH with James R. Mueller assisted by many, especially Amy-Jill Levine, Randall D. Chesnutt, and M. J. H. Charlesworth ATLA BIBLIOGRAPHY SERIES, MO. 17 The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Metuchen, N.J., and London • 1987 CONTENTS Editor's Foreword xiii Preface xv I. INTRODUCTION 1 A Report on Research 1 Description 6 Excluded Documents 6 1) Apostolic Fathers 6 2) The Nag Hammadi Codices 7 3) The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha 7 4) Early Syriac Writings 8 5) Earliest Versions of the New Testament 8 6) Fakes 9 7) Possible Candidates 10 Introductions 11 Purpose 12 Notes 13 II. THE APOCALYPSE OF JOHN—ITS THEOLOGY AND IMPACT ON SUBSEQUENT APOCALYPSES Introduction . 19 The Apocalypse and Its Theology . 19 1) Historical Methodology 19 2) Other Apocalypses 20 3) A Unity 24 4) Martyrdom 25 5) Assurance and Exhortation 27 6) The Way and Invitation 28 7) Transference and Redefinition -. 28 8) Summary 30 The Apocalypse and Its Impact on Subsequent Apocalypses 30 1) Problems 30 2) Criteria 31 3) Excluded Writings 32 4) Included Writings 32 5) Documents , 32 a) Jewish Apocalypses Significantly Expanded by Christians 32 b) Gnostic Apocalypses 33 c) Early Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 34 d) Early Medieval Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 36 6) Summary 39 Conclusion 39 1) Significance 39 2) The Continuum 40 3) The Influence 41 Notes 42 III. THE CONTINUUM OF JEWISH AND CHRISTIAN APOCALYPSES: TEXTS AND ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS Description of an Apocalypse 53 Excluded "Apocalypses" 54 A List of Apocalypses 55 1) Classical Jewish Apocalypses and Related Documents (c. -

1 Peter “Be Holy”

1 Peter “Be Holy” Bible Knowledge Commentary States: “First Peter was written to Christians who were experiencing various forms of persecution, men and women whose stand for Jesus Christ made them aliens and strangers in the midst of a pagan society. Peter exhorted these Christians to steadfast endurance and exemplary behavior. The warmth of his expressions combined with his practical instructions make this epistle a unique source of encouragement for all believers who live in conflict with their culture. I. Setting 1 Peter is the 19th book of the New Testament and 16th among the Epistles or letters. They are the primary doctrinal portions of the New Testament. It is not that the Gospels and Acts do not contain doctrine, but that the purpose of the Epistles is to explain to churches and individuals how to apply the teachings of Jesus. Jesus’ earthly life models ministry. In every area of ministry, we must apply the example of Christ. He was filled with the Spirit, sought to honor God, put a high value on people, and lowered Himself as the servant of all. Once He ascended to heaven, He poured His Spirit out on believers and the New Testament church was formed. Acts focuses on the birth, establishment, and furtherance of the work of God in the world, through the church. The Epistles are written to the church, further explaining doctrine. A. 1Peter is part of a section among the Epistles commonly known as “The Hebrew Christian Epistles” and includes Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, 1st, 2nd and 3rd John and Jude. -

GBNT-500 Acts of the Apostles Cmt 1566614590902

GBNT 500 The Acts of the Apostles 7th Revision, October 2011 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology Acts of the Apostles GBNT 500 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology 1 This material is not to be copied for any purpose without written permission from American Mission Teams © Copyright by American Mission Teams, Inc., All rights reserved, printed in the United States of America GBNT 500 The Acts of the Apostles 7th Revision, October 2011 Midwest Seminary of Bible Theology ARE YOU BORN AGAIN? Knowing in your heart that you are born-again and followed by a statement of faith are the two prerequisites to studying and getting the most out of your MSBT materials. We at MSBT have developed this material to educate each Believer in the principles of God. Our goal is to provide each Believer with an avenue to enrich their personal lives and bring them closer to God. Is Jesus your Lord and Savior? If you have not accepted Him as such, you must be aware of what Romans 3:23 tells you. 23 For all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God: How do you go about it? You must believe that Jesus is the Son of God. I John 5:13 gives an example in which to base your faith. 13 These things have I written unto you that believe on the name of the Son of God; that ye may know that ye have eternal life, and that ye may believe on the name of the Son of God. What if you are just not sure? Romans 10:9-10 gives you the Scriptural mandate for becoming born-again. -

PAULINE CHRISTIANITY: Luke-Acts and the Legacy of Paul

PAULINE CHRISTIANITY: Luke-Acts and the Legacy of Paul CHRISTOPHER MOUNT BRILL NTS.Mount.vw104e 07-11-2001 13:58 Pagina 1 PAULINE CHRISTIANITY NTS.Mount.vw104e 07-11-2001 13:58 Pagina 2 SUPPLEMENTS TO NOVUM TESTAMENTUM EDITORIAL BOARD C.K. BARRETT, Durham - P. BORGEN, Trondheim J.K. ELLIOTT, Leeds - H. J. DE JONGE, Leiden A. J. MALHERBE, New Haven M. J. J. MENKEN, Utrecht - J. SMIT SIBINGA, Amsterdam Executive Editors M.M. MITCHELL, Chicago & D.P. MOESSNER, Dubuque VOLUME CIV NTS.Mount.vw104e 07-11-2001 13:58 Pagina 3 PAULINE CHRISTIANITY Luke-Acts and the Legacy of Paul BY CHRISTOPHER MOUNT BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2002 NTS.Mount.vw104e 07-11-2001 13:58 Pagina 4 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Mount, Christopher Luke-acts and the legacy of Paul Boston ; Köln : Brill, 2002 (Supplements to Novum testamentum ; Vol. 104) ISBN 90–04–12472–1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is also available ISSN 0167-9732 ISBN 90 04 12472 1 © Copyright 2002 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. -

Acts 1-5 Adult Religion Class New Testament, Lesson 21 26 February 2018

“We All Are Witnesses” Dave LeFevre Acts 1-5 Adult Religion Class New Testament, Lesson 21 26 February 2018 “We All Are Witnesses” Acts 1-5 Introduction Acts was written by the same author as the gospel of Luke, as a second part to his story about Jesus, and to the same person, Theophilus. While the gospel covers the life and teachings of Jesus, Acts continues that story into the early church, showing its growth and spread from Judea to Samaria to the Gentiles. Even so, there are several examples where a topic or concept introduced in the gospel of Luke is continued in Acts. It is likely that the two were divided because together they exceeded the standard length of a scroll—there was too much content for a single parchment document. The book was possibly written during the time of Paul’s first imprisonment in Rome, about A.D. 57-59. Luke was clearly a companion of Paul (see Colossians 4:14; 2 Timothy 4:11; Philemon 1:24) and had firsthand knowledge of his activities. Little is known about Luke himself, but a second-century source said that he was a “Syrian of Antioch, by profession a physician,” and that he followed Paul until the apostle’s martyrdom. “He died at the age of eighty- four in Boeotia [a region in central Greece], full of the Holy Spirit.”1 Though it’s called “The Acts of the Apostles,” a better title might be “The Acts of Peter and Paul.” Acts is divided roughly in two, with chapters 1-12 having Peter as the main character (though with some good details about Stephen, Philip, James, and others), and chapters 13-28 mainly focused on Paul. -

History of the Christian Church, Volume I: Apostolic Christianity

History of the Christian Church, Volume I: Apostolic Christianity. A.D. 1-100. by Philip Schaff About History of the Christian Church, Volume I: Apostolic Christianity. A.D. 1-100. by Philip Schaff Title: History of the Christian Church, Volume I: Apostolic Christianity. A.D. 1-100. URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/hcc1.html Author(s): Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) Publisher: CCEL First Published: 1882 Print Basis: Revised edition Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2002-11-26 Contributor(s): Wendy Huang (Markup) CCEL Subjects: All; History; LC Call no: BR145.S3 1882-1910 LC Subjects: Christianity History History of the Christian Church, Volume I: Apostolic Christianity. Philip Schaff A.D. 1-100. Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii History of the Christian Church. p. 1 Preface to the Revised Edition. p. 1 From the Preface to the First Edition. p. 2 Preface to the Third Revision. p. 3 Contents. p. 4 Addenda. p. 4 Literature. p. 6 Nature of Church History. p. 7 Branches of Church History. p. 10 Sources of Church History. p. 12 Periods of Church History. p. 13 Uses of Church History. p. 17 Duty of the Historian. p. 18 Literature of Church History. p. 21 Preparation for Christianity in the History of the Jewish. p. 36 Central Position of Christ in the History of the World. p. 37 Judaism. p. 38 The Law, and the Prophecy. p. 43 Heathenism. p. 46 Grecian Literature, and the Roman Empire. p. 49 Judaism and Heathenism in Contact. p. 54 Jesus Christ. p. 57 Sources and Literature. -

The Influence of 1 Corinthians on the Acts of Paul

The Influence of 1 Corinthians on the Acts of Paul by Peter W. Dunn Reprinted with minor corrections by the author from Society of Biblical Literature 1996 Seminar Papers (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1996) pp. 438-454 The Influence of 1 Corinthians on the Acts of Paul1 Peter W. Dunn Ontario Theological Seminary According to Tertullian (bapt. 17), an Asian Presbyter (henceforth, “the Presbyter”) wrote the Acts of Paul (APl) and later resigned his office because of the scandal which his writing had caused. The general reaction in the early church, however, seems to have been much more favorable, for the APl enjoyed widespread dissemination and acceptance. Its story of Paul is fascinating, portraying him as a wandering missionary and wonder-worker who creates disturbances everywhere he goes, though he always manages to convert not a few and escape, until his martyrdom at the hands of Nero. In the most celebrated section of the APl, known as the Acts of Paul and Thecla (AThl), Paul turns a certain Thecla away from her fiancé, Thamyris, to embrace Christianity and chastity. Thamyris takes his revenge by stirring the mobs and the authorities against both his fiancée and the Apostle. Scholars often consider this very vivid image of the Apostle to be a gross deviation from the historical Paul. In the first critical monograph on the AThl, C. Schlau2 set the tone for how scholars would treat the Paulinism of the APl. He could detect only a single phrase which was reminiscent of the authentic Paul: Bezeichnen schon die Reden des Apostels Paulus in der Apostelgeschichte des Lucas, verglichen mit seinen Briefen, eine gewisse Neutralisirung der specifischen Gedanken des Apostels, so ist in unsern Acten diese Neutralisirung in einem Grade fortgeschritten, dass die dem Paulus in dem [sic] Mund gelegten Reden, abgesehen von dem einmal (c. -

By Philip Schaff VOLUME 1. First Period

a Grace Notes course History of the Christian Church By Philip Schaff VOLUME 1. First Period – Apostolic Christianity 1 Chapter 12: The New Testament 1 Editor: Warren Doud History of the Christian Church VOLUME 1. First Period – Apostolic Christianity Contents Volume 1, Chapter 12. The New Testament .................................................................................3 1.74 Literature. .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.75 Rise of the Apostolic Literature. ................................................................................................ 3 1.76 Character of the New Testament. ............................................................................................. 4 1.77 Literature on the Gospels. ......................................................................................................... 6 1.78 The Four Gospels. ...................................................................................................................... 8 1.79 The Synoptists. ......................................................................................................................... 11 1.80 Matthew. ................................................................................................................................. 20 1.81 Mark. ........................................................................................................................................ 25 1.82 Luke. ........................................................................................................................................ -

Copyright © 2014 Sean Joslin Mcdowell All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2014 Sean Joslin McDowell All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation, or instruction. A HISTORICAL EVALUATION OF THE EVIDENCE FOR THE DEATH OF THE APOSTLES AS MARTYRS FOR THEIR FAITH __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Sean Joslin McDowell December 2014 APPROVAL SHEET A HISTORICAL EVALUATION OF THE EVIDENCE FOR THE DEATH OF THE APOSTLES AS MARTYRS FOR THEIR FAITH Sean Joslin McDowell Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ James Parker III (Chair) __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin __________________________________________ Theodore J. Cabal Date ______________________________ To Stephanie This was truly a team effort. I could not ask for a more loving and supportive wife. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . ix PREFACE . x Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Methodology . 4 Defining Martyrdom . 6 Challenges for the Historical Investigation . 11 Research Outline . 20 2. THE CENTRALITY OF THE RESURRECTION . 23 Early Christian Creeds . 24 First Corinthians 15:3-7 . 26 The Resurrection in Acts and the Letters of Paul . 29 Resurrection in the Apostolic Fathers . 31 Conclusion . 32 3. THE TWELVE APOSTLES . 34 Who Were the Twelve? . 35 The Historicity of the Twelve . 39 The Apostolic Witness . 41 All the Apostles . 43 Did The Apostles Engage in Missionary Work? . 44 The Testimony of the Twelve . 54 iv Chapter Page 4. PERSECUTION IN THE EARLY CHURCH . -

Paul Miraculous

PAUL and the MIRACULOUS A Historical Reconstruction GRAHAM H. TWELFTREE K Graham H. Twelftree, Paul and the Miraculous Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2013. Used by permission. (Unpublished manuscript—copyright protected Baker Publishing Group) Twelftree_Miraculous_BB_mw.indd iii 7/3/13 4:14 PM © 2013 by Graham H. Twelftree Published by Baker Academic a division of Baker Publishing Group P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287 www.bakeracademic.com Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Twelftree, Graham H. Paul and the miraculous : a historical reconstruction / Graham H. Twelftree pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8010-2772-7 (pbk.) 1. Paul, the Apostle, Saint. 2. Miracles. I. Title. BS2506.3.T84 2013 225.9 2—dc23 2013012180 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Graham H. Twelftree, Paul and the Miraculous Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2013. Used by permission. (Unpublished manuscript—copyright protected Baker Publishing Group) Twelftree_Miraculous_BB_mw.indd iv 7/3/13 4:14 PM To Stephen H. -

Between Canonical and Apocryphal Texts

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) · James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) · Janet Spittler (Charlottesville, VA) J. Ross Wagner (Durham, NC) 419 Between Canonical and Apocryphal Texts Processes of Reception, Rewriting, and Interpretation in Early Judaism and Early Christianity Edited by Jörg Frey, Claire Clivaz, and Tobias Nicklas in collaboration with Jörg Röder Mohr Siebeck Jörg Frey, born 1962; 1996 Dr. theol.; 1998 Habilitation; since 2010 Professor for New Testament at the University of Zurich. Claire Clivaz, born 1971; 2007 PhD; since 2014 Invited Professor in Digital Humanities at the University of Lausanne; since 2015 Head of Digital Enhanced Learning at the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics in Lausanne. Tobias Nicklas, born 1967; 2000 Dr. theol.; 2004 Habilitation; since 2007 Professor for Exegesis und Hermeneutics of the New Testament at the University of Regensburg. Jörg Röder, born 1980; since 2014 Researcher for the HyperNT Project (New Testament Studies), University of Basel. ISBN 978-3-16-153927-5 / eISBN 978-3-16-155232-8 DOI 10.1628/978-3-16-155232-8 ISSN 0512-1604 / eISSN 2568-7476 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. -

The Holy See

The Holy See BENEDICT XVI GENERAL AUDIENCE Paul VI Audience Hall Wednesday, 4 February 2009 Saint Paul (20): St Paul's martyrdom and heritage Dear Brothers and Sisters, The series of our Catecheses on St Paul has come to its conclusion; today we shall speak of the end of his earthly life. The ancient Christian tradition witnesses unanimously that Paul died as a consequence of his martyrdom here in Rome. The New Testament writings tell us nothing of the event. The Acts of the Apostles end their account by mentioning the imprisonment of the Apostle, who was nevertheless able to welcome all who went to him (cf. Acts 28: 30-31). Only in the Second Letter to Timothy do we find these premonitory words: "For I am already on the point of being sacrificed"; the time to set sail has come (2 Tm 4: 6; cf. Phil 2: 17). Two images are used here, the religious image of sacrifice that he had used previously in the Letter to the Philippians, interpreting martyrdom as a part of Christ's sacrifice, and the nautical image of casting off: two images which together discreetly allude to the event of death and of a brutal death. The first explicit testimony of St Paul's death comes to us from the middle of the 90s in the first century, thus more than three decades after his actual death. It consists precisely in the Epistle that the Church of Rome, with its Bishop Clement I, wrote to the Church of Corinth. In that epistolary text is an invitation to keep her eyes fixed on the example of the Apostles and, immediately after the mention of Peter's martyrdom, one reads: "Owing to envy, Paul also obtained the reward of patient endurance, after being seven times thrown into captivity, compelled to flee, and stoned.