The Terminology of Batak Musical Instruments in Northern Sumatra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sada Borneo Band Profile

SADA BORNEO BAND PROFILE “KEEP OUR LEGACY” OFFICIAL BAND WEBSITE: www.sadaborneo.wix.com/official FACEBOOK PAGE: www.facebook.com/sadaborneo INSTAGRAM: sadaborneo TWITTER: @Sada_Borneo OFFICIAL EMAIL: [email protected] / +6012-682 4449 (Andy Siti - Manager) SADA BORNEO is a Malaysian band formed in Penang in 2013 and consists of 8 members from different parts of Malaysia. Aspired to create a new sound for Malaysian music to show the beauty of Malaysia, their music is a fusion of traditional, modern, ethnic and nature elements blend in together. The meaning behind the name 'SADA BORNEO' is 'the sound of Borneo', borrowing Sarawak's Iban ethnic word 'Sada', which means 'sound'. SADA BORNEO gained popularity for representing Malaysia in AXN's ASIA’S GOT TALENT 2015 and being the only Malaysian that made it to Semi Final stage. The show was aired in 20 countries across Asia. Sada Borneo has also received the IKON NEGARAKU 2017 AWARD by the Prime Minister Office. From left: Hilmi, Allister, Julian (behind), Nick (front), Hallan (front), Bob (behind), Wilker and Alvin “We create new sounds by fusing modern western, traditional Malaysian, ethnic-oriented elements and sounds of nature in our musical arrangement and composition. Instrumentation-wise, we featured various traditional music instruments such as Sapeh and recreate the sounds of nature elements to produce a contemporary sound.” – SADA BORNEO From left (sitting) : Alvin, Bob, Hallan, Wilker, Hilmi, Julian From left (standing) : Allister, Nick ABOUT THE BAND SADA BORNEO'S music formula includes reviving traditional music, fresh and contemporary elements into their music arrangement and composition. The band loves to experiment with various kinds of musical instruments, ranging from traditional to modern musical instruments. -

Bodies of Sound, Agents of Muslim Malayness: Malaysian Identity Politics and The

Bodies of Sound, Agents of Muslim Malayness: Malaysian Identity Politics and the Symbolic Ecology of the Gambus Lute Joseph M. Kinzer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Christina Sunardi, Chair Patricia Campbell Laurie Sears Philip Schuyler Meilu Ho Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Joseph M. Kinzer iii University of Washington Abstract Bodies of Sound, Agents of Muslim Malayness: Malaysian Identity Politics and the Symbolic Ecology of the Gambus Lute Joseph M. Kinzer Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Christina Sunardi Music In this dissertation, I show how Malay-identified performing arts are used to fold in Malay Muslim identity into the urban milieu, not as an alternative to Kuala Lumpur’s contemporary cultural trajectory, but as an integrated part of it. I found this identity negotiation occurring through secular performance traditions of a particular instrument known as the gambus (lute), an Arabic instrument with strong ties to Malay history and trade. During my fieldwork, I discovered that the gambus in Malaysia is a potent symbol through which Malay Muslim identity is negotiated based on various local and transnational conceptions of Islamic modernity. My dissertation explores the material and virtual pathways that converge a number of historical, geographic, and socio-political sites—including the National Museum and the National Conservatory for the Arts, iv Culture, and Heritage—in my experiences studying the gambus and the wider transmission of muzik Melayu (Malay music) in urban Malaysia. I argue that the gambus complicates articulations of Malay identity through multiple agentic forces, including people (musicians, teachers, etc.), the gambus itself (its materials and iconicity), various governmental and non-governmental institutions, and wider oral, aural, and material transmission processes. -

Research Article Investigation of the Acoustic Properties of Chemically Impregnated Kayu Malam Wood Used for Musical Instrument

Hindawi Advances in Materials Science and Engineering Volume 2018, Article ID 7829613, 6 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7829613 Research Article Investigation of the Acoustic Properties of Chemically Impregnated Kayu Malam Wood Used for Musical Instrument Md. Faruk Hossen ,1,2 Sinin Hamdan,1 and Md. Rezaur Rahman1 1Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia 2Faculty of Science, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi 6205, Bangladesh Correspondence should be addressed to Md. Faruk Hossen; [email protected] Received 12 October 2017; Accepted 22 November 2017; Published 29 April 2018 Academic Editor: Aniello Riccio Copyright © 2018 Md. Faruk Hossen et al. )is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. )e chemical modification or impregnation through preparing the wood polymer composites (WPCs) can effectively reduce the hygroscopicity as well as can improve the acoustic properties of wood. On the other hand, a small amount of nanoclay into the chemical mixture can further improve the different properties of the WPCs through the preparation of wood polymer nano- composites (WPNCs). Kayu Malam wood species with styrene (St), vinyl acetate (VA), and montmorillonite (MMT) nanoclay were used for the preparation of WPNCs. )e acoustic properties such as specific dynamic Young’s modulus (Ed/γ), internal friction (Q−1), and acoustic conversion efficiency (ACE) of wood were examined using free-free flexural vibration. It was observed that the chemically impregnated wood composite showed a higher value of Ed/γ than raw wood and the nanoclay-loaded wood nanocomposite showed the highest value. -

THE EDUCATIVE IMPACT of MUSIC STUDY ABROAD by Daniel Antonelli Dissertation Committee

THE EDUCATIVE IMPACT OF MUSIC STUDY ABROAD by Daniel Antonelli Dissertation Committee: Professor Randall E. Allsup, Sponsor Professor Lori A. Custodero Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 10 February, 2021 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2021 ABSTRACT THE EDUCATIVE IMPACT OF MUSIC STUDY ABROAD Daniel Antonelli This study explored the educative impact of a music study abroad program, specifically, what role music plays in encounters between students from diverse cultural backgrounds, and how such programs can help shape the identity of a global citizen and lead to a more socially just global community. If programmatic efforts can be impactful, preparing young people for life in a more interdependent, complex, and fragile world, then how can such values be informed, fostered, and even stimulated by engaging in international music travel? How is “difference” experienced and rendered meaningful? This qualitative case study followed U.S. music and music education students on a trip to Malaysia where they collaborated with Malaysian peers in bamboo instrument-making as well as music-making in traditional Malay styles. Perspectives, commentary, and reflections of and by all participants were recorded and investigated. Pre-trip interviews were conducted two months prior to embarking on the international journey. During the program abroad over the course of three weeks, I interviewed four U.S. music students, five Malaysian music education students, and both a U.S. and Malay music professor. Additionally, a focus group was conducted with the Malay student-participants. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Hanafi Hussin, BRANDING MALAYSIA and RE-POSITIONING

JATI-Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Special Issue 2018 (Rebranding Southeast Asia), 74-91 BRANDING MALAYSIA AND RE-POSITIONING CULTURAL HERITAGE IN TOURISM DEVELOPMENT Hanafi Hussin Department of Southeast Asian Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences (IOES) University of Malaya ([email protected]) Doi: https://doi.org/10.22452/ jati.sp2018no1.6 Abstract In the regional and global competitive tourism sector, branding Malaysia as Turley Asian has maximally helped the country. The branding efforts have facilitated Malaysia to present itself as a true sign of pluralism, a mixture of harmonious cultures and the true soul of Asia. The intangible cultural heritage especially food heritage and traditional performing arts have also significantly contributed to branding ‘Malaysia Truly Asia’. The multiple traditional and cultural performances represent multicultural Malaysia. In these performances, all ethnic groups, i.e. Indian, Chinese, Malay, Indigenous and others are represented adequately. Malaysian traditional cuisine also represents the pluralism of Malaysian society. Authentic and hybrid foods and the traditional performing arts have made the country a mini Asia or the soul of Asia. Understanding the position and contribution of both traditional food and performing arts to promote Malaysian tourism under the slogan of ‘Malaysia Truly Asia’ is extremely important in developing the Malaysian tourism sector. Under the concepts of identity and culture as a segment of branding approaches, this article will analyse how cultural heritage has helped to brand Malaysia as Truly Asia for the development of the tourism sector of Malaysia. Keywords: branding, intangible cultural heritage, ‘Malaysia Truly Asia’, tourism, Malaysia 74 Branding Malaysia and Re-Positioning Cultural Heritage in Tourism Development Introduction The concept of cultural heritage serves various cultural, social and political purposes (Blake, 2000). -

Pengenalan Alat Muzik | String Instruments

Pengenalan alat muzik..... Pengenalan Laman Web Alat Muzik Tradisional Malaysia ini dibangunkan dengan tujuan untuk mewarwarkan kepada masyarakat sejagat terutama generasi muda. Disamping itu dapat memberi pemahaman lebih jelas tentang rupabentuk dan fungsi serta bunyi alat muzik itu. Skop maklumat alat muzik tradisional ini amatlah terbatas, ianya masih terdapat masa kini dan terus diterima pakai oleh bangsa di Malaysia.Kami berusaha membangunkan web ini semungkin yang boleh dan pertambahan maklumat serta paparan artifak yang menarik akan dikemaskini dari semasa ke semasa. Secara amnya, selain daripada digunakan untuk menghasilkan berbagai jenis muzik, alat alat muzik ini merupakan bahan estetika yang penting dalam masyarakat. Ia digunakan sebagai alat penyebar maklumat, lambang budaya bangsa, alat ritual yang dapat menghubungkan manusia dengan alam luar biasa(magis) selain dari fungsi utama sebagai alat hiburan. Terdapat lima kategori Alat Muzik Tradisional: Kordofon Membranofon Alat-alat muzik kordofon ialah alat- Dalam kategori ini digolongkan alat- alat yang mengeluarkan bunyi kerana alat muzik yang menghasilkan bunyi adanya getaran pada tali yang melalui kulit atau membrane yang ditegangkan. Alat-alat muzik rebab, ditegang dan dipalu.Berbagai jenis sape dan lain-lain tergolong dalam alat gendang dan rebana Melayu kategori ini. tergolong dalam kategori membranofon. Kebiasaannya digunakan di dalam menghasilkan lagu-lagu rakyat. Erofon Idiofon Erofon adalah alat-alat muzik yang Idiofon adalah alat- menghasilkan bunyi melalui lubang menghasilkan b udara. Dalam masyarakat pribumi tindakbalas pada ran Malaysia,terdapat beberapa jenis alat bergema. Contoh al muzik erofon seperti serunai, seruling, pribumi Malaysia ialah nafiri, seruling hidung dan lain lain dan jenis-jenisnya. yang sejenis. idiofon terdapat 'metallophone', daripada logam gang dan gendir dalam ense Erofon Bebas Erofon bebas adalah suatu alat muzik yang menghasilkan bunyi melalui lubang udara dengan car meniupnya, penjenisan alat adalah berbeza dari erofon. -

Candidate Music Genre/Form Terms for Discussion

Candidate Music Genre/Form Terms for Discussion This list, which is primarily derived from Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). was last updated on March 22, 2013. The list should not be used as a source of current LCSH vocabulary, as LCSH terms may be modified in between updates. KEY TO STATUS COLUMN cancel:LCMPT = cancel heading:use Library of Congress Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music (LCMPT). LCSH heading will be cancelled unless already used topically; medium terms will be available in LCMPT. The final forms of terms as incorporated into LCMPT will not necessarily be exactly as the terms appear in this list. cancel:LCMPT+LCGFT = cancel heading:use LCMPT and Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Library and Archival Materials (LCGFT). Add medium terms to LCMPT; add genre terms to LCGFT. The final forms of terms as incorporated into LCMPT and LCGFT will not necessarily be exactly as the terms appear in this list. cancel:OutOfScopeLCGFT = cancel heading:terms with a language qualifier and text names are out of scope for LCGFT. carrier = carrier/extent term. Not in scope for LCGFT; may be in scope for LCMPT. LCSH = invalid as genre/form or medium of performance term; used as a topical term in LCSH. LCGFT = add to Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Library and Archival Materials. The final forms of terms as incorporated into LCGFT will not necessarily be exactly as the terms appear in this list. -

Cahiers D'ethnomusicologie, 16

Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie Anciennement Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 16 | 2003 Musiques à voir Musiques traditionnelles d'Indonésie Une anthologie de vingt disques Dana Rappoport Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/634 ISSN : 2235-7688 Éditeur ADEM - Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 novembre 2003 Pagination : 239-253 ISBN : 978-2-8257-0863-7 ISSN : 1662-372X Référence électronique Dana Rappoport, « Musiques traditionnelles d'Indonésie », Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie [En ligne], 16 | 2003, mis en ligne le 16 janvier 2012, consulté le 21 avril 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/634 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 avril 2019. Tous droits réservés Musiques traditionnelles d'Indonésie 1 Musiques traditionnelles d'Indonésie Une anthologie de vingt disques1 Dana Rappoport Liste des CD Lieu et titre Populations Résumé 1. Songs before Dawn: Javanais Ile de Java Est Gandrung Banyuwangi. CD Une chanteuse-danseuse - autrefois un jeune SF 40055, DDD, 1991, 11 travesti - divertit les invités masculins lors de plages, enregistrements cérémonies. Au flux ininterrompu de la voix 1990, notice, 4 p., anglais, féminine s'oppose le caractère terrestre de la voix 2 photos. masculine, sur un petit ensemble musical. (2 violons, triangle, 2 tambours, 2 gongs bulbés, gong suspendu) 2. Indonesian Popular Music: Betawi Ile de Java Kroncong, Dangdut and Indonésien Deux formes musicales nées dans les classes Langgam Jawa. CD SF e Javanais sociales pauvres de Jakarta, l'une à la fin du XIX 40056, DDD, 1991, 15 siècle et l'autre dans les années 1960, aujourd'hui plages, plages 1-5 Sokha portées au rang de musique nationale. -

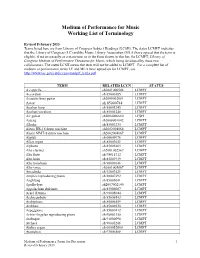

Medium of Performance for Music: Working List of Terminology

Medium of Performance for Music Working List of Terminology Revised February 2013 Terms listed here are from Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). The status LCMPT indicates that the Library of Congress (LC) and the Music Library Association (MLA) have agreed that the term is eligible, if not necessarily as a main term or in the form shown in this list, for LCMPT, Library of Congress Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music, which being developed by these two collaborators. The status LCSH means the term will not be added to LCMPT. For a complete list of medium of performance terms LC and MLA have agreed on for LCMPT, see http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/medprf_lcmla.pdf. -

Sanggit Dan Garap Pertunjukan Wayang Kulit Jawatimuran Gaya Malangan Lakon Menarisinga Sajian Suyanto

SANGGIT DAN GARAP PERTUNJUKAN WAYANG KULIT JAWATIMURAN GAYA MALANGAN LAKON MENARISINGA SAJIAN SUYANTO SKRIPSI KARYA ILMIAH oleh Moch. Hanafi Permana Putra NIM 15123103 FAKULTAS SENI PERTUNJUKAN INSTITUT SENI INDONESIA SURAKARTA 2019 SANGGIT DAN GARAP PERTUNJUKAN WAYANG KULIT JAWATIMURAN GAYA MALANGAN LAKON MENARISINGA SAJIAN SUYANTO SKRIPSI KARYA ILMIAH Untuk memenuhi sebagian persyaratan guna mencapai derajat Sarjana S-1 Program Studi Seni Pedalangan Jurusan Seni Pedalangan oleh Moch. Hanafi Permana Putra NIM 15123103 FAKULTAS SENI PERTUNJUKAN INSTITUT SENI INDONESIA SURAKARTA 2019 ii MOTTO Nek dolan sampek bengi utawa nganti isuk oleh, tapi ojo lali karo kewajiban ndunya lan akhirate - Supiyanto - (jika bermain sampai larut malam atau hingga pagi hari boleh, tetapi jangan sampai lupa dengan kewajiban dunia dan akhiratnya) PERSEMBAHAN Skripsi Karya Ilmiah ini saya persembahkan kepada: Bapak Supiyanto dan Ibu Supriyatin tercinta Keluarga besar yang selalu mendukung saya Sekolah dan Almamater kebanggaan Rekan-rekan prodi pedalangan 2015 Semua yang telah membantu prosesku iii iv ABSTRAK Penelitian berjudul “Sanggit dan Garap Pertunjukan Wayang Kulit Jawatimuran Gaya Malangan Lakon Menarisinga Sajian Suyanto” bertujuan untuk menjawab permasalahan tentang: (1) Bagaimana struktur dramatik lakon Menarisinga sajian Suyanto; dan (2) Bagaimana sanggit dan garap lakon Menarasinga sajian Suyanto. Teori yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah struktur dramatik yang dikemukakan oleh Soediro Satoto dan Sumanto untuk menganalisis alur, latar/setting, penokohan, tema, dan amanat. Teori sanggit dan garap dari Sugeng Nugroho untuk mengkaji ide garap dan implementasi dalam lakon Menarisinga. Analisis pada penelitan ini bersifat deskriptif kualitatif, yang diperoleh dari pengumpulan data dengan langkah-langkah studi pustaka, wawancara, dan observasi. Hasil penelitian menunjukan bahwa sanggit dan garap pertunjukan wayang kulit Jawatimuran gaya Malangan lakon Menarisinga sajian Suyanto memiliki ciri khas sebagai bentuk pakeliran gaya kerakyatan. -

Draft Authorized Vocabulary for Medium of Performance Statements

MEDIUM OF PERFORMANCE TERMS FOR LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MEDIUM OF PERFORMANCE THESAURUS FOR MUSIC DRAFT AUTHORIZED VOCABULARY FOR MEDIUM OF PERFORMANCE STATEMENTS IN BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORDS AS AGREED ON BY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS AND THE MUSIC LIBRARY ASSOCIATION February 2013 Introduction The Library of Congress, in cooperation with the Music Library Association, is developing a new thesaurus of terms representing vocabulary for the medium of performance of musical works, Library of Congress Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music (LCMPT). The vocabulary is intended to be used, at least initially, for two bibliographic purposes: 1) to retrieve music by its medium of performance in library catalogs, as is now done by the controlled vocabulary, Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH); 2) to record the element “medium of performance” of musical works according to the cataloging standard, RDA: Resource Description and Access (RDA). The table that follows, which contains approximately 850 terms, updates the previously posted table of terms the collaborators recommend for the new medium of performance thesaurus. The table is a working document, subject to change. Background Medium of performance is now recognized as a separate and distinct bibliographic facet that should have its own vocabulary and vocabulary structure. Searches by medium should enable users to retrieve music by a particular instrument or instrumental group, voice or vocal group, or other medium of performance term or terms the searcher may specify. As presently incorporated into LCSH, medium of performance terms may occur in headings in two ways: either along with a term for genre, form, type, or style of music (as in Sonatas (Violin and piano)), or in headings that have only one or more medium terms in them (as in Violin and piano music).