From Arabic Style Toward Javanese Style: Comparison Between Accents of Javanese Recitation and Arabic Recitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

A Practical Sanskrit Introductory

A Practical Sanskrit Intro ductory This print le is available from ftpftpnacaczawiknersktintropsjan Preface This course of fteen lessons is intended to lift the Englishsp eaking studentwho knows nothing of Sanskrit to the level where he can intelligently apply Monier DhatuPat ha Williams dictionary and the to the study of the scriptures The rst ve lessons cover the pronunciation of the basic Sanskrit alphab et Devanagar together with its written form in b oth and transliterated Roman ash cards are included as an aid The notes on pronunciation are largely descriptive based on mouth p osition and eort with similar English Received Pronunciation sounds oered where p ossible The next four lessons describ e vowel emb ellishments to the consonants the principles of conjunct consonants Devanagar and additions to and variations in the alphab et Lessons ten and sandhi eleven present in grid form and explain their principles in sound The next three lessons p enetrate MonierWilliams dictionary through its four levels of alphab etical order and suggest strategies for nding dicult words The artha DhatuPat ha last lesson shows the extraction of the from the and the application of this and the dictionary to the study of the scriptures In addition to the primary course the rst eleven lessons include a B section whichintro duces the student to the principles of sentence structure in this fully inected language Six declension paradigms and class conjugation in the present tense are used with a minimal vo cabulary of nineteen words In the B part of -

GWJ Drewes, AH Johns, the Gift Addressed to the Spirit of The

Book Reviews - G.W.J. Drewes, A.H. Johns, The gift addressed to the spirit of the prophet. Oriental Monograph Series No. 1. Centre of Oriental Studies. The Australian National University, Canberra 1965. 224 pp. - , In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 122 (1966), no: 2, Leiden, 290-300 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 03:50:30PM via free access BOEKBESPREKINGEN The Gift addressed to the Spirit of the Prophet by Dr. A. H. JOHNS, Professor of Indonesian Languages and Literatures. Oriental Monograph Series No. 1. Centre of Oriental Studies. The Australian National University, Canberra 1965. 224 pp. 8°. The title of this book is that of the Arabic text and its versified Javanese adaptation which are both published here together with an English translation. The Arabic text has been prepared by Dr P. Voorhoeve from the manuscripts of the work and the commentaries on it preserved in the Oriental Department of the University library at Leiden. The Javanese text is based on two MSS., British Museum Add 12305 and Cod. or. 5594 Leiden. The author of the Arabic work was an Indian Muslim, Muhammad ibn Fadlallah al-Burhanpürï, who died in 1620. As to the age of the Javanese adaptation the conclusion arrived at by Professor Johns is that the nucleus of the text was in existence in the second half of the 18th century, although the original work must have been known in Java at least one hundred year earlier. I am inclined to disagree with Professor Johns' opinion that the Javanese poet did his work in Tegal arurn at the behest of the Javanese governor of that region. -

M. Ricklefs an Inventory of the Javanese Manuscript Collection in the British Museum

M. Ricklefs An inventory of the Javanese manuscript collection in the British Museum In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 125 (1969), no: 2, Leiden, 241-262 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 11:29:04AM via free access AN INVENTORY OF THE JAVANESE MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM* he collection of Javanese manuscripts in the British Museum, London, although small by comparison with collections in THolland and Indonesia, is nevertheless of considerable importance. The Crawfurd collection, forming the bulk of the manuscripts, provides a picture of the types of literature being written in Central Java in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a period which Dr. Pigeaud has described as a Literary Renaissance.1 Because they were acquired by John Crawfurd during his residence as an official of the British administration on Java, 1811-1815, these manuscripts have a convenient terminus ad quem with regard to composition. A large number of the items are dated, a further convenience to the research worker, and the dates are seen to cluster in the four decades between AD 1775 and AD 1815. A number of the texts were originally obtained from Pakualam I, who was installed as an independent Prince by the British admini- stration. Some of the manuscripts are specifically said to have come from him (e.g. Add. 12281 and 12337), and a statement in a Leiden University Bah ad from the Pakualaman suggests many other volumes in Crawfurd's collection also derive from this source: Tuwan Mister [Crawfurd] asked to be instructed in adat law, with examples of the Javanese usage. -

The Local Wisdom in Javanese Thinking Culture Within Hanacaraka Philosophy

THE LOCAL WISDOM IN JAVANESE THINKING CULTURE WITHIN HANACARAKA PHILOSOPHY Fitriana Kartika Sari STKIP PGRI Ponorogo email: [email protected] Abstract (Title: The Local Wisdom In Javanese Thinking Culture Within Hanacaraka Philosophy). Hanacaraka refers to the written language of Javanese, Javanese script. The name is based on the order of the twenty-Javanese-script, which is started by the series of hanacaraka script. This study aims to describe the local wisdom content of Javanese Thinking culture within the philosophical meaning of hanacaraka. This study used a semiotic approach applied to the main data source, namely Sêrat Kérata Basa. The results showed that (1) the philosophical meaning of the hanacaraka script was fully equipped with the wisdom of Javanese thinking culture in the form of symbolism and othak-athik mathuk which is supported by deep contemplation which involves all the common senses, including the inner sensitivity; (2) hanacaraka philosophy depicts God creature’s (human) circumstances, which is equipped with creation, feeling, and effort; human cannot avoid all God’s fate upon them until the end of their life; human conditions that achieve life harmony due to the ability to unify the manifestation of God and human characteristics, which heats up within themselves; human condition which put God’s order highly by doing all the orders and avoiding all of His warnings. Keywords: local wisdom, Javanese thinking, Hanacaraka INTRODUCTION because human is always eager to know and Javanese local wisdom is the principal find the authentic truth for everything. Human factor of thoughtful thinking which covers tries to seek for the revelating indicator of all then aspects of knowledge, faith, mysteries deeply through the use of all the comprehension or understanding, customs, common senses to gain satisfying conclusive and ethics. -

"9-41516)9? "9787:)4 ;7 -6+7,- )=1 16 ;0- & $

L2/20-256 "9-41516)9?"9787:)4;7-6+7,-)=116;0-&$ ᭛᭜᭛ <;079 ,1;?))?<"-9,)6)215-14,7;3755/5)14+75 40)5 <9=)6:)0140)56<9=)6:)0/5)14+75 );- ;0$-8;-5*-9 6;97,<+;176 ,=:#6L>H8G>EI>H6=>HIDG>86AG6=B>76H:9H8G>EI;DJC9>CK6G>DJH>CH8G>EI>DCH6C96GI:;68IHEGD9J8:97:IL::CI=: I=6C9I=: I=8:CIJGN>C>CHJA6G+DJI=:6HIH>6A6G<:EDGI>DCD;>IH8DGEJH>H;DJC9>C"6K67JI#6L>B6I:G>6AH =6K:6AHD7::C;DJC9>C+JB6IG6%6A6N(:C>CHJA66A>6C9I=:(=>A>EE>C:H,=:H8G>EI>H;G:FJ:CIAN6HHD8>6I:9L>I= I=:'A9"6K6C:H:A6C<J6<:7JIB6I:G>6AHLG>II:C>C+6CH@G>I'A9%6A6N'A96A>C:H:6C9'A9+JC96C:H:A6C<J6<: =6H6AHD7::C;DJC9>CI=:#6L>H8G>EIGDBI=:B>9I=8:CIJGNH>BEA:;JC8I>DC6A#6L>L6HL>9:ANJH:9IDG:8DG9 A6C9 <G6CIH GDN6A :9>8IH 6C9 H>B>A6G 8=6C8:GN 9D8JB:CIH ,DL6G9H I=: :C9 D; I=: ;>GHI B>AA:CC>JB I=: H8G>EI 7:86B:>C8G:6H>C<AN9:8DG6I>K:6C986AA><G6E=>89J:ID>IHJH:6HI=:B6>CK:=>8A:D;'A9"6K6C:H:A>I:G6GNA6C<J6<: L>I=ADC<A6HI>C<A:<68N>CI=:A>I:G6GNIG69>I>DCD;I=:BD9:GC"6K6C:H:6C96A>C:H:A6C<J6<:H$6I:G#6L>H=DLH B6CNK6G>6I>DCHDK:G6L>9:<:D<G6E=>89>HIG>7JI>DC'K:GI>B:I=:H:K6G>6CIH=6K::KDAK:9>G:8IANDG>C9>G:8IAN >CIDI=:B6CNBD9:GCG6=B>8H8G>EIHD;>CHJA6G+H>6HJ8=6H6A>C:H:6I6@"6K6C:H:$DCI6G6:I8 /=>A:I=:68I>K:JH:D;#6L>H8G>EI=6H7::CG:EA68:97NDI=:GH8G>EIHH>C8:I=: I=8:CIJGNI=:G:6G:6CJB7:GD; BD9:GC96N:CI=JH>6HIH6C98DBBJC>I>:HL=DJH:I=:H8G>EIID96N;DGDI=:GEJGEDH:HI=6C6C8>:CIG:EGD9J8I>DC ;DG:M6BEA:ID8=6I>CHD8>6A6EEA>86I>DC6C98G:6I:>B6<:EDHIH!CI=>HG:K>K6AINE:D;JH:I=:#6L>H8G>EIB6N7: JH:9IDLG>I:A6C<J6<:HI=6I6G:CDI;DJC9>C‘6JI=:CI>8’#6L>8DGEJHHJ8=6HI=:BD9:GC"6K6C:H:A6C<J6<:DG I=: !C9DC:H>6C A6C<J6<: H#6L>=6H CDI 7::C :C8D9:9>C I=: -C>8D9: N:I I=: -

Design of Javanese Text to Speech Application

Design of Javanese Text to Speech Application Yulia, Liliana, Rudy Adipranata, Gregorius Satia Budhi Informatics Department, Industrial Technology Faculty, Petra Christian University Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—Javanese is one of the many regional languages used in Indonesia. Javanese language is used by most of the population in Java. But now along with the development of the era, the use of regional languages including Javanese language is to be re- duced especially among the younger generation. One way to help conserve the use of Javanese language is to utilize information technologies, one of them is by developing a text to speech appli- cation that can be used to find out how the pronunciation of Ja- vanese language. In this paper, we discussed the design for Java- nese text to speech applications uses finite state automata. The design result will be used as rules to separate syllables when im- plementing text to speech application. Index Terms—Javanese language; Finite state automata; Text to speech. Figure 1: Basic Javanese characters I. INTRODUCTION In addition to the basic characters, the Javanese character Javanese language is a language widely spoken by the peo- has supplementary characters, consist of symbols for express- ple of Java. It is one of the regional languages of many region- ing vowels as well as a combination of two specific conso- al languages spoken in Indonesia. As one of the assets of na- nants. This supplementary characters is called sandhangan tional culture, Javanese language needs to be preserved. The and can be seen in Figure 2 [5]. younger generation is now more interested in learning a for- Symbol Example Read eign language, rather than the native Indonesian local lan- guage. -

Ahom Range: 11700–1174F

Ahom Range: 11700–1174F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms Range: FF00–FFEF

Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms Range: FF00–FFEF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

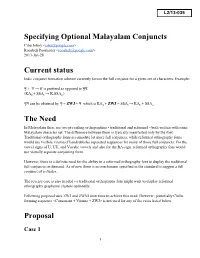

Specifying Optional Malayalam Conjuncts

Specifying Optional Malayalam Conjuncts Cibu Johny <[email protected]> Roozbeh Poornader <[email protected]> 2013Jan28 Current status Indic conjunct formation scheme currently favors the full conjunct for a given set of characters. Example: क् + ष → is prefered as opposed to क् ष. (KAd + SSAl → K.SSAn ) क् ष can be obtained by क् + ZWJ + ष which is KAd + ZWJ + SSAl → KAh + SSAn The Need In Malayalam there are two prevailing orthographies traditional and reformed both written with same Malayalam character set. The difference between them is typically manifested only by the font. Traditional orthography fonts accomodate lot more full conjuncts, while reformed orthography fonts would use visibile virama (Chandrakkala) separated sequences for many of those full conjuncts. For the vowel signs of U, UU, and Vocalic vowels and also for the RAsign, reformed orthography font would use visually separate conjoining form. However, there is a definite need for the ability in a reformed orthography font to display the traditional full conjuncts on demand. As of now there is no mechanism specified in the standard to suggest a full conjunct of a cluster. The reverse case is also needed a traditional orthography font might want to display reformed othrography grapheme clusters optionally. Following proposal uses ZWJ and ZWNJ insertions to achieve this need. However, potentially Chillu forming sequence <Consonant + Virama + ZWJ> is not used for any of the cases listed below. Proposal Case 1 1 The sequence <Consonant + ZWJ + Conjoining Vowel Sign> has following fallback order for display: 1. Full Conjunct 2. Consonant + nonconjoining vowel sign Example with reformed orthography font (in a reformed orthography Malayalam font that can allow optional traditional orthography) SA + Vowel Sign U → SA + ZWJ + Vowel Sign U → Case 2 <Consonant1 + ZWJ + Virama + Consonant2> has following display fallback order: 1. -

Yi Syllables Range: A000–A48F

Yi Syllables Range: A000–A48F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

The Song of Macapat Semarangan: the Acculturation of Javanese and Islamic Culture

Harmonia: Journal of Arts Research and Education 20 (1) (2020), 10-18 p-ISSN 2541-1683|e-ISSN 2541-2426 Available online at http://journal.unnes.ac.id/nju/index.php/harmonia DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15294/harmonia.v20i1.25050 The Song of Macapat Semarangan: The Acculturation of Javanese and Islamic Culture Agus Cahyono, Widodo Widodo, Muhamad Jazuli, Onang Murtiyoso Department of Drama, Dance, and Music, Faculty of Languages and Arts, Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia Submitted: January 4, 2020. Revised: March 9, 2020. Accepted: July 4, 2020 Abstract The research objective is to explain the macapat Semarangan song which is the result of accul- turation of Javanese and Islamic culture. The study used qualitative methods by uncovering the concept of processing of Javanese music and acculturation. Research location was in Semarang with the object of macapat Semarangan song study. Data was collected through interviews, ob- servations, and study documents. The validity of the data was examined through triangulation techniques and the analysis is done through the stages of identification, classification, compari- son, interpretation, reduction, verification, and making conclusions. The results showed that the macapat Semarangan song has unique characteristics of arrangement. The song’s grooves use long and complicated musical ornamentations with varying pitch heights to reach high notes. This is a manifestation of the results of acculturation of Javanese and Islamic culture seen from arrange- ment on the parts of Adzan (call to prayer) and tilawatil Qur’an. The process of acculturation of elements of Islamic culture also involves scales. Azan songs use diatonic scales, some macapat Semarangan songs also use the same scales, but a cycle of five notes close to nuances of Chi- nese music scales.