GWJ Drewes, AH Johns, the Gift Addressed to the Spirit of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Arabic Style Toward Javanese Style: Comparison Between Accents of Javanese Recitation and Arabic Recitation

From Arabic Style toward Javanese Style: Comparison between Accents of Javanese Recitation and Arabic Recitation Nur Faizin1 Abstract Moslem scholars have acceptedmaqamat in reciting the Quran otherwise they have not accepted macapat as Javanese style in reciting the Quran such as recitationin the State Palace in commemoration of Isra` Miraj 2015. The paper uses a phonological approach to accents in Arabic and Javanese style in recitingthe first verse of Surah Al-Isra`. Themethod used here is analysis of suprasegmental sound (accent) by usingSpeech Analyzer programand the comparison of these accents is analyzed by descriptive method. By doing so, the author found that:first, there is not any ideological reason to reject Javanese style because both of Arabic and Javanese style have some aspects suitable and unsuitable with Ilm Tajweed; second, the suitability of Arabic style was muchthan Javanese style; third, it is not right to reject recitingthe Quran with Javanese style only based on assumption that it evokedmistakes and errors; fourth, the acceptance of Arabic style as the art in reciting the Quran should risedacceptanceof the Javanese stylealso. So, rejection of reciting the Quranwith Javanese style wasnot due to any reason and it couldnot be proofed by any logical argument. Keywords: Recitation, Arabic Style, Javanese Style, Quran. Introduction There was a controversial event in commemoration of Isra‘ Mi‘raj at the State Palacein Jakarta May 15, 2015 ago. The recitation of the Quran in the commemoration was recitedwithJavanese style (langgam).That was not common performance in relation to such as official event. Muhammad 58 Nur Faizin, From Arabic Style toward Javanese Style Yasser Arafat, a lecture of Sunan Kalijaga State Islamic University Yogyakarta has been reciting first verse of Al-Isra` by Javanese style in the front of state officials and delegationsof many countries. -

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

Masks in Javanese Dance-Dramas Author(S): Soedarsono Source: the World of Music , 1980, Vol

Masks in Javanese Dance-Dramas Author(s): Soedarsono Source: The World of Music , 1980, Vol. 22, No. 1, masks (1980), pp. 5-22 Published by: VWB - Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43560649 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms , and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The World of Music This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Sun, 25 Jul 2021 07:56:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Soedarsono Masks in Javanese Dance-Dramas Speaking about masks in Javanese dance-dramas stimulates me to trace back the functions of the masks in the past, with the hope that it may clarify the hidden meaning of their roles in their aesthetic uses. Today, a mask literally means a cover for the face usually as a disguise or protection. In Javanese dance it means a cover for the face depicting a character in a story. The Uses of Masks in the Past Among the various religious rites of the primitive Javanese people was ancestor worship. It was done by using human or animal statues as the media of worship. -

The Local Wisdom in Javanese Thinking Culture Within Hanacaraka Philosophy

THE LOCAL WISDOM IN JAVANESE THINKING CULTURE WITHIN HANACARAKA PHILOSOPHY Fitriana Kartika Sari STKIP PGRI Ponorogo email: [email protected] Abstract (Title: The Local Wisdom In Javanese Thinking Culture Within Hanacaraka Philosophy). Hanacaraka refers to the written language of Javanese, Javanese script. The name is based on the order of the twenty-Javanese-script, which is started by the series of hanacaraka script. This study aims to describe the local wisdom content of Javanese Thinking culture within the philosophical meaning of hanacaraka. This study used a semiotic approach applied to the main data source, namely Sêrat Kérata Basa. The results showed that (1) the philosophical meaning of the hanacaraka script was fully equipped with the wisdom of Javanese thinking culture in the form of symbolism and othak-athik mathuk which is supported by deep contemplation which involves all the common senses, including the inner sensitivity; (2) hanacaraka philosophy depicts God creature’s (human) circumstances, which is equipped with creation, feeling, and effort; human cannot avoid all God’s fate upon them until the end of their life; human conditions that achieve life harmony due to the ability to unify the manifestation of God and human characteristics, which heats up within themselves; human condition which put God’s order highly by doing all the orders and avoiding all of His warnings. Keywords: local wisdom, Javanese thinking, Hanacaraka INTRODUCTION because human is always eager to know and Javanese local wisdom is the principal find the authentic truth for everything. Human factor of thoughtful thinking which covers tries to seek for the revelating indicator of all then aspects of knowledge, faith, mysteries deeply through the use of all the comprehension or understanding, customs, common senses to gain satisfying conclusive and ethics. -

2016 Semi Finalists Medals

2016 US Physics Olympiad Semi Finalists Medal Rankings StudentMedal School City State Abbott, Ryan WHopkinsBronze Medal SchoolNew Haven CT Alton, James SLakesideHonorable Mention High SchoolEvans GA ALUMOOTIL, VARKEY TCanyonHonorable Mention Crest AcademySan Diego CA An, Seung HwanGold Medal Taft SchoolWatertown CT Ashary, Rafay AWilliamHonorable Mention P Clements High SchoolSugar Land TX Balaji, ShreyasSilver Medal John Foster Dulles High SchoolSugar Land TX Bao, MikeGold Medal Cambridge Educational InstituteChino Hills CA Beasley, NicholasGold Medal Stuyvesant High SchoolNew York NY BENABOU, JOSHUA N Gold Medal Plandome NY Bhattacharyya, MoinakSilver Medal Lynbrook High SchoolSan Jose CA Bhattaram, Krishnakumar SLynbrookBronze Medal High SchoolSan Jose CA Bhimnathwala, Tarung SBronze Medal Manalapan High SchoolManalapan NJ Boopathy, AkhilanGold Medal Lakeside Upper SchoolSeattle WA Cao, AntonSilver Medal Evergreen Valley High SchoolSan Jose CA Cen, Edward DBellaireHonorable Mention High SchoolBellaire TX Chadraa, Dalai BRedmondHonorable Mention High SchoolRedmond WA Chakrabarti, DarshanBronze Medal Northside College Preparatory HSChicago IL Chan, Clive ALexingtonSilver Medal High SchoolLexington MA Chang, Kevin YBellarmineSilver Medal Coll PrepSan Jose CA Cheerla, NikhilBronze Medal Monta Vista High SchoolSan Jose CA Chen, AlexanderSilver Medal Princeton High SchoolPrinceton NJ Chen, Andrew LMissionSilver Medal San Jose High SchoolFremont CA Chen, Benjamin YArdentSilver Medal Academy for Gifted YouthIrvine CA Chen, Bryan XMontaHonorable -

Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms Range: FF00–FFEF

Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms Range: FF00–FFEF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0--Online Edition

This PDF file is an excerpt from The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0, issued by the Unicode Consor- tium and published by Addison-Wesley. The material has been modified slightly for this online edi- tion, however the PDF files have not been modified to reflect the corrections found on the Updates and Errata page (http://www.unicode.org/errata/). For information on more recent versions of the standard, see http://www.unicode.org/standard/versions/enumeratedversions.html. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The Unicode® Consortium is a registered trademark, and Unicode™ is a trademark of Unicode, Inc. The Unicode logo is a trademark of Unicode, Inc., and may be registered in some jurisdictions. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. -

Yi Syllables Range: A000–A48F

Yi Syllables Range: A000–A48F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Old Javanese Legal Traditions in Pre-Colonial Bali

HELEN CREESE Old Javanese legal traditions in pre-colonial Bali Law codes with their origins in Indic-influenced Old Javanese knowledge sys- tems comprise an important genre in the Balinese textual record. Significant numbers of palm-leaf manuscripts, as well as later printed copies in Balinese script and romanized transliteration, are found in the major manuscript col- lections. A general overview of the Old Javanese legal corpus is included in Pigeaud’s four-volume catalogue of Javanese manuscripts, Literature of Java, under the heading ‘Juridical Literature’ (Pigeaud 1967:304-14, 1980:43), but detailed studies remain the exception. In spite of the considerable number of different legal treatises extant, and the insights they provide into pre-colonial judicial practices and forms of government, there have only been a handful of studies of Old Javanese and Balinese legal texts. A succession of nineteenth-century European visitors, ethnographers and administrators, notably Thomas Stamford Raffles (1817), John Crawfurd (1820), H.N. van den Broek (1854), Pierre Dubois,1 R. Friederich (1959), P.L. van Bloemen Waanders (1859), R. van Eck (1878-80) and Julius Jacobs (1883), routinely described legal practices in Bali, but European interest in Balinese legal texts was rarely philological. The first legal text to be published was a Dutch translation, without a word of commentary or explanation, of a section of the Dewadanda (Blokzeijl 1872). Then, in the early twentieth cen- tury, after the establishment of Dutch colonial rule over the entire island in 1908, Balinese (Djilantik and Oka 1909a, 1909b) and later Malay (Djlantik and Schwartz 1918a, 1918b, 1918c) translations of certain law codes were produced at the behest of Dutch officials who maintained that the Balinese priests who were required to administer adat law were unable to understand 1 Pierre Dubois,’Idée de Balie; Brieven over Balie’, [1833-1835], in: KITLV, H 281. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0

Pau Cin Hau Range: 11AC0–11AFF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Introduction to Old Javanese Language and Literature: a Kawi Prose Anthology

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES THE MICHIGAN SERIES IN SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS Editorial Board Alton L. Becker John K. Musgrave George B. Simmons Thomas R. Trautmann, chm. Ann Arbor, Michigan INTRODUCTION TO OLD JAVANESE LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE: A KAWI PROSE ANTHOLOGY Mary S. Zurbuchen Ann Arbor Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan 1976 The Michigan Series in South and Southeast Asian Languages and Linguistics, 3 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-16235 International Standard Book Number: 0-89148-053-6 Copyright 1976 by Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-053-2 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12818-1 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90218-7 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ I made my song a coat Covered with embroideries Out of old mythologies.... "A Coat" W. B. Yeats Languages are more to us than systems of thought transference. They are invisible garments that drape themselves about our spirit and give a predetermined form to all its symbolic expression. When the expression is of unusual significance, we call it literature. "Language and Literature" Edward Sapir Contents Preface IX Pronounciation Guide X Vowel Sandhi xi Illustration of Scripts xii Kawi--an Introduction Language ancf History 1 Language and Its Forms 3 Language and Systems of Meaning 6 The Texts 10 Short Readings 13 Sentences 14 Paragraphs.. -

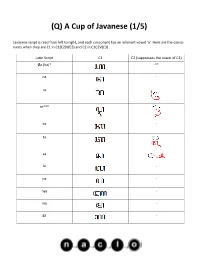

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2.