T. Behrend the Writings of KPH Suryanagara; Shifting Paradigms in Nineteenth-Century Javanese Thought and Letters In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Arabic Style Toward Javanese Style: Comparison Between Accents of Javanese Recitation and Arabic Recitation

From Arabic Style toward Javanese Style: Comparison between Accents of Javanese Recitation and Arabic Recitation Nur Faizin1 Abstract Moslem scholars have acceptedmaqamat in reciting the Quran otherwise they have not accepted macapat as Javanese style in reciting the Quran such as recitationin the State Palace in commemoration of Isra` Miraj 2015. The paper uses a phonological approach to accents in Arabic and Javanese style in recitingthe first verse of Surah Al-Isra`. Themethod used here is analysis of suprasegmental sound (accent) by usingSpeech Analyzer programand the comparison of these accents is analyzed by descriptive method. By doing so, the author found that:first, there is not any ideological reason to reject Javanese style because both of Arabic and Javanese style have some aspects suitable and unsuitable with Ilm Tajweed; second, the suitability of Arabic style was muchthan Javanese style; third, it is not right to reject recitingthe Quran with Javanese style only based on assumption that it evokedmistakes and errors; fourth, the acceptance of Arabic style as the art in reciting the Quran should risedacceptanceof the Javanese stylealso. So, rejection of reciting the Quranwith Javanese style wasnot due to any reason and it couldnot be proofed by any logical argument. Keywords: Recitation, Arabic Style, Javanese Style, Quran. Introduction There was a controversial event in commemoration of Isra‘ Mi‘raj at the State Palacein Jakarta May 15, 2015 ago. The recitation of the Quran in the commemoration was recitedwithJavanese style (langgam).That was not common performance in relation to such as official event. Muhammad 58 Nur Faizin, From Arabic Style toward Javanese Style Yasser Arafat, a lecture of Sunan Kalijaga State Islamic University Yogyakarta has been reciting first verse of Al-Isra` by Javanese style in the front of state officials and delegationsof many countries. -

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

Southeast Asia: History, Modernity, and Religious Change

AL ALBAB - Borneo Journal of Religious Studies (BJRS) Volume 2 Number 2 December 2013 SOUTHEAST ASIA: HISTORY, MODERNITY, AND RELIGIOUS CHANGE Sumanto Al Qurtuby University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies Abstract Southeast Asia or Southeastern Asia, with more than six hundred million pop- ulations, is home to millions of Buddhists, Muslims, Confucians, Protestants, Catholics, and now Pentecostals, as well as many followers of local religions and spiritual beliefs. Notwithstanding its great historical, political, cultural legacies, however, the region has long been neglected as a site for religious studies in the Western academia. Aiming at filling the gap in Asian and religious studies as well as exploring the richness of Southeast Asian cultures, this article discusses the dynamics, diversity, and complexity of Southeast Asian societies in their re- sponse to the region’s richly political, cultural, and religious traditions spanning from pre-modern era to modern one. The article also examines the “integrative revolutions” that shaped and reshaped warfare, state organization and econom- ics of Southeast Asia, particularly in the pre-European colonial era. In addition, the work discusses the wave of Islamization, particularly since the nineteenth century, as well as the upsurge of religious resurgence that shift the nature of religiosity and the formation of religious groupings in the area. The advent of Islam, with some interventions of political regimes, had been an important cause for the decline of Hindu-Buddhist traditions in some areas of Southeast Asia, especially Indonesia, the coming of Pentecostalism has challenged the well-estab- lished mainstream Protestantism and Catholicism, especially in Indonesia and the Philippines. -

GWJ Drewes, AH Johns, the Gift Addressed to the Spirit of The

Book Reviews - G.W.J. Drewes, A.H. Johns, The gift addressed to the spirit of the prophet. Oriental Monograph Series No. 1. Centre of Oriental Studies. The Australian National University, Canberra 1965. 224 pp. - , In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 122 (1966), no: 2, Leiden, 290-300 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 03:50:30PM via free access BOEKBESPREKINGEN The Gift addressed to the Spirit of the Prophet by Dr. A. H. JOHNS, Professor of Indonesian Languages and Literatures. Oriental Monograph Series No. 1. Centre of Oriental Studies. The Australian National University, Canberra 1965. 224 pp. 8°. The title of this book is that of the Arabic text and its versified Javanese adaptation which are both published here together with an English translation. The Arabic text has been prepared by Dr P. Voorhoeve from the manuscripts of the work and the commentaries on it preserved in the Oriental Department of the University library at Leiden. The Javanese text is based on two MSS., British Museum Add 12305 and Cod. or. 5594 Leiden. The author of the Arabic work was an Indian Muslim, Muhammad ibn Fadlallah al-Burhanpürï, who died in 1620. As to the age of the Javanese adaptation the conclusion arrived at by Professor Johns is that the nucleus of the text was in existence in the second half of the 18th century, although the original work must have been known in Java at least one hundred year earlier. I am inclined to disagree with Professor Johns' opinion that the Javanese poet did his work in Tegal arurn at the behest of the Javanese governor of that region. -

The Local Wisdom in Javanese Thinking Culture Within Hanacaraka Philosophy

THE LOCAL WISDOM IN JAVANESE THINKING CULTURE WITHIN HANACARAKA PHILOSOPHY Fitriana Kartika Sari STKIP PGRI Ponorogo email: [email protected] Abstract (Title: The Local Wisdom In Javanese Thinking Culture Within Hanacaraka Philosophy). Hanacaraka refers to the written language of Javanese, Javanese script. The name is based on the order of the twenty-Javanese-script, which is started by the series of hanacaraka script. This study aims to describe the local wisdom content of Javanese Thinking culture within the philosophical meaning of hanacaraka. This study used a semiotic approach applied to the main data source, namely Sêrat Kérata Basa. The results showed that (1) the philosophical meaning of the hanacaraka script was fully equipped with the wisdom of Javanese thinking culture in the form of symbolism and othak-athik mathuk which is supported by deep contemplation which involves all the common senses, including the inner sensitivity; (2) hanacaraka philosophy depicts God creature’s (human) circumstances, which is equipped with creation, feeling, and effort; human cannot avoid all God’s fate upon them until the end of their life; human conditions that achieve life harmony due to the ability to unify the manifestation of God and human characteristics, which heats up within themselves; human condition which put God’s order highly by doing all the orders and avoiding all of His warnings. Keywords: local wisdom, Javanese thinking, Hanacaraka INTRODUCTION because human is always eager to know and Javanese local wisdom is the principal find the authentic truth for everything. Human factor of thoughtful thinking which covers tries to seek for the revelating indicator of all then aspects of knowledge, faith, mysteries deeply through the use of all the comprehension or understanding, customs, common senses to gain satisfying conclusive and ethics. -

Masked Panji Plays in Nineteenth-Century Java the Story of Kuda Narawangsa

PB Wacana Vol. 21 No. 1 (2020) Clara Brakel-PapenhuyzenWacana Vol., Masked 21 No. Panji 1 (2020): plays in 1-27 nineteenth-century Java 1 Masked Panji plays in nineteenth-century Java The story of Kuda Narawangsa Clara Brakel-Papenhuyzen ABSTRACT This article discusses the Javanese Panji-story Kuda Narawangsa, which I first watched as a masked performance in a village south of Yogyakarta in 1977. The play featured Galuh Candra Kirana, spouse of Prince Panji of Jenggala, in the masculine form of “Kuda Narawangsa”. Historical information on this play in archival manuscript sources, found mainly in the collections of Leiden University Libraries, proves that it was well-known in Java during the nineteenth century. In this article, descriptions of performances in manuscripts or printed publications are combined with historical play-scripts (pakem) from Surakarta and Yogyakarta, which have not been investigated so far. Special attention is paid to the script of a masked performance of the Kuda Narawangsa story in a manuscript from the Mangkunegaran palace, investigating what this historical pakem can tell us about the meaning and context of a masked performance of this story in nineteenth century Java. A story which according to recent publications remains relevant in Indonesian society to this day.1 KEYWORDS Javanese Panji stories; Kuda Narawangsa; Javanese masked drama (topeng dhalang); Javanese play-scripts (pakem). 1 See among others, Dwi Yulianti 2017. Clara Brakel-Papenhuyzen has lectured at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia and at Leiden University (PhD 1988). Her scholarly research on languages, cultures, and performing arts of South and Southeast Asia was always combined with practice of dance, theatre, and music. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0

Pau Cin Hau Range: 11AC0–11AFF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Birds, Bards, Buffoons and Brahmans

Archipel Études interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien 88 | 2014 Varia Birds, Bards, Buffoons and Brahmans : (Re-)Tracing the Indic Roots of some Ancient and Modern Performing Characters from Java and Bali Oiseaux, bardes, bouffons et brahmanes : en retraçant les racines indiennes de certains personnages de spectacle anciens et modernes de Java et de Bali Andrea Acri Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/archipel/555 DOI: 10.4000/archipel.555 ISSN: 2104-3655 Publisher Association Archipel Printed version Date of publication: 10 October 2014 Number of pages: 13-70 ISBN: 978-2-910513-71-9 ISSN: 0044-8613 Electronic reference Andrea Acri , “Birds, Bards, Buffoons and Brahmans : (Re-)Tracing the Indic Roots of some Ancient and Modern Performing Characters from Java and Bali ”, Archipel [Online], 88 | 2014, Online since 10 September 2017, connection on 27 August 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/555 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.555 Association Archipel VARIA ANDREA ACRI 1 Birds, Bards, Buffoons and Brahmans: (Re-)Tracing the Indic Roots of some Ancient and Modern Performing Characters from Java and Bali 2 Introduction12 On the basis of evidence gathered from Old Javanese textual sources—most notably the 9th-century Old Javanese Rāmāyaṇa kakavin (RK) and the early 13th-century Sumanasāntaka3—and Central Javanese temple reliefs, I have elsewhere proposed to identify some figures of itinerant ascetics-cum-performers (e.g. thevidu s, Old Jav./Skt. vidu)4 as localised counterparts of Indic prototypes, namely low-status, 1. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, Singapore. 2. (1) The spelling of Old Javanese words follows the system used in Acri 2011b, discussed in Acri and Griffiths 2014 (e.g. -

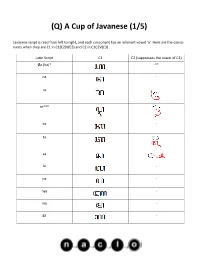

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2. -

Javanese Language Preservation in the Global Era: Determining Effective Teaching Methods for Elementary School Students Advances

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 www.alls.aiac.org.au Javanese Language Preservation in the Global Era: Determining Effective Teaching Methods for Elementary School Students Lusia Neti Harwati* Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Brawijaya University, Jalan Veteran Malang, East Java, Indonesia Corresponding Author: Lusia Neti Harwati, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Previous studies on Javanese language emphasized more on the use of this local language in Received: March 14, 2018 certain communities and ignored the importance of teaching and learning at an elementary Accepted: May 21, 2018 school level in order to preserve the language. The purpose of this study was to describe the Published: August 31, 2018 lives of the participants, collect and tell stories about their lives, and then write narratives of Volume: 9 Issue: 4 their experiences. The data were gathered through the collection of stories, reporting individual Advance access: July 2018 experiences, and discussing the meaning of those experiences for the participants by proposing a research question: what is the story of the teachers who tried to preserve Javanese language in the global era? A narrative research design, sociolinguistics, and social change as theories Conflicts of interest: None were applied in order to understand teachers’ point of view on globalization and the importance Funding: The research is financed by of preserving Javanese language. Purposeful sampling was used and two teachers were chosen DPP/SPP 2016, Faculty of Cultural as participants. The data gathered were then analyzed through three steps, namely code the Sciences, Brawijaya University data, description, and interpretation. -

Grantha Range: 11300–1137F

Grantha Range: 11300–1137F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Aspek Fiqih Perempuan Dalam Serat Centhini; Tinjauan Feminisme

ASPEK FIQIH PEREMPUAN DALAM SERAT CENTHINI; TINJAUAN FEMINISME S K R I P S I Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Dan Melengkapi Syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Program Strata 1 (S.1) Dalam Ilmu Syari’ah Oleh : ZAKI MUBAROK NIM : 2102181 JURUSAN AL-AHWAL AL-SYAKHSIYAH FAKULTAS SYARI’AH INSTITUT AGAMA ISLAM NEGERI WALISONGO SEMARANG 2009 Drs. H. Abu Hafsin, MA, Ph.D Dosen Fakultas Syari’ah IAIN Walisongo Semarang A. Arief Junaidi M.Ag Dosen Fakultas Syari’ah IAIN Walisongo Semarang Nota Pembimbing Semarang, 30 Desember 2008 Lamp : 4 (Empat) Eksemplar Kepada : Hal : Naskah Skripsi Yth. Dekan Fakultas Syari’ah a.n. sdr. Zaki Mubarok IAIN Walisongo Di Semarang Assalamu’alaikum Wr. Wb. Setelah saya mengadakan koreksi dan perbaikan seperlunya maka bersama ini saya kirimkan naskah skripsi saudara: Nama : ZAKI MUBAROK NIM : 2102181 Jurusan : Ahwal al-Syakhsiyah Judul Skripsi : Aspek Fiqih Perempan dalam Serat Centhini; Tinjauan Feminisme Dengan ini saya mohon kiranya skripsi sauadara tersebut segera dimunaqasahkan. Atas perhatiannya saya ucapkan terima kasih. Wassalamu’alaikum Wr. Wb. Pembimbing I Pembimbing II Drs. H. Abu Hafsin, MA Ph.D A. Arif Junaidi M. Ag NIP. 150 238 492 NIP. 150 276 119 DEPARTEMEN AGAMA INSTITUT AGAMA ISLAM NEGERI WALISONGO FAKULTAS SYARI'AH Jl. Prof. Dr. Hamka Km. 02 Telp. (024) 7601291 Semarang 50185 PENGESAHAN Skripsi Saudara : Zaki Mubarok NIM : 2102181 Judul : Aspek Fiqih Perempuan dalam Serat Centhini; Tinjauan Feminisme Telah dimunaqasahkan oleh Dewan Penguji Fakultas Syari’ah Institut Agama Islam Negeri Walisongo Semarang, dan dinyatakan lulus dengan predikat cumlaude / baik / cukup , pada tanggal : 14 Januari 2009 Dan dapat diterima sebagai kelengkapan ujian akhir dalam rangka menyelesaikan studi Program Sarjana Strata 1 (S.1) tahun akademik 2008/2009 guna memperoleh gelar sarjana dalam Ilmu Syari’ah.