LANGUAGES of the LAND a RESOURCE MANUAL for ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Land Claims and the Future of Archaeology in the Northwest Territories, Canada Thomas D

17 Native Land Claims and the Future of Archaeology in the Northwest Territories, Canada Thomas D. Andrews Charles D. Arnnold Elisa J. Hart Margaret M. Bertulli The settlement of comprehensive land claims is ushering in major changes in the manage ment of land and resources in the Northwest Territories, including heritage resources. This chap ter summarizes the progress that has been made in completing land claims, anticipates the impact that the claims will have on the way archaeological research is conducted, and discusses how the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) is responding to these changes. Suggestions for dealing with the current social and political setting in the design and implementation of archaeological projects are also presented. OUTLINE OF NATIVE LAND CLAIMS IN THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES In the early 1970s, the Government of Canada established a comprehensive claims policy to guide negotiations with Native groups in settling Aboriginal interests in lands that they tradition ally occupied. Although the Northwest Territories has its own legislative assembly and its own bureaucracy to administer most of the business of government, the Government of Canada has the sole responsibility for settling Aboriginal land claims in the Northwest Territories. The Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Territories are the Inuit, the Dene, the Cree, and the Metis. The Inuit include the Inuvialuit of the Beaufort Sea and Amundson Gulf areas of the west ern Arctic, who, in 1984, were the first Aboriginal group in the Northwest Territories to settle a land claim with the Government of Canada (see Figure 1). In May, 1993, the Inuit of the eastern Arctic, an area commonly referred to as “Nunavut” signed a final agreement on a land claim. -

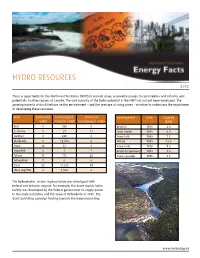

Hydro Energy in The

HYDRO RESOURCES 2012 There is opportunity for the Northwest Territories (NWT) to provide clean, renewable energy to communities and industry, and potentially to other regions of Canada. The vast majority of the hydro potential in the NWT has not yet been developed. The growing impacts of fossil fuel use on the environment – and the pressure of rising prices – continue to underscore the importance of developing these resources. River Developed Undeveloped Proposed Development Date Capacity (MW) Potential (MW) Development (MW) (MW) Bear 0 568 0 Bluefish 1938 3.0 La Martre 0 27 13 Snare Rapids 1948 8.0 Lockhart 0 269 0 Snare Falls 1960 7.5 Mackenzie 0 10,450 0 Taltson 1965 18.0 Snare 30 33 0 Snare Forks 1976 9.0 Snowdrift 0 1 1 Bluefish Expansion 1994 4.0 Taltson 18 172 56 Snare Cascades 1996 4.3 Yellowknife 7 0 0 Total 55 11,520 69 Slave (AB/NT) 0 1,500 0 The hydroelectric system in place today was developed with federal and industry support. For example, the Snare Rapids hydro facility was developed by the federal government to supply power to the Giant Gold Mine and the town of Yellowknife in 1948. The Giant Gold Mine provided funding towards the transmission line. www.nwtenergy.ca In the 1960’s, a hydro plant on the Taltson River was constructed to supply power to the Pine Point Cominco Mine site and the communities of Pine Point and Fort Smith, and was supported by the federal government. The commissioning of the Taltson Hydroelectric Development occurred in 1965 and the facility now supplies power to the communities of Fort Smith, Fort Resolution, Hay River, Enterprise and the Hay River Reserve. -

The Rose Collection of Moccasins in the Canadian Museum of Civilization : Transitional Woodland/Grassl and Footwear

THE ROSE COLLECTION OF MOCCASINS IN THE CANADIAN MUSEUM OF CIVILIZATION : TRANSITIONAL WOODLAND/GRASSL AND FOOTWEAR David Sager 3636 Denburn Place Mississauga, Ontario Canada, L4X 2R2 Abstract/Resume Many specialists assign the attribution of "Plains Cree" or "Plains Ojibway" to material culture from parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In fact, only a small part of this area was Grasslands. Several bands of Cree and Ojibway (Saulteaux) became permanent residents of the Grasslands bor- ders when Reserves were established in the 19th century. They rapidly absorbed aspects of Plains material culture, a process started earlier farther west. This paper examines one such case as revealed by footwear. Beaucoup de spécialistes attribuent aux Plains Cree ou aux Plains Ojibway des objets matériels de culture des régions du Manitoba ou de la Saskatch- ewan. En fait, il n'y a qu'une petite partie de cette région ait été prairie. Plusieurs bandes de Cree et d'Ojibway (Saulteaux) sont devenus habitants permanents des limites de la prairie quand les réserves ont été établies au XIXe siècle. Ils ont rapidement absorbé des aspects de la culture matérielle des prairies, un processus qu'on a commencé plus tôt plus loin à l'ouest. Cet article examine un tel cas comme il est révélé par des chaussures. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies XIV, 2(1 994):273-304. 274 David Sager The Rose Moccasin Collection: Problems in Attribution This paper focuses on a unique group of eight pair of moccasins from southern Saskatchewan made in the mid 1880s. They were collected by Robert Jeans Rose between 1883 and 1887. -

Indigenous Languages

INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES PRE-TEACH/PRE-ACTIVITY Have students look at the Indigenous languages and/or language groups that are displayed on the map. Discuss where this data came from (the 2016 census) and what biases or problems this data may have, such as the fear of self-identifying based on historical reasons or current gaps in data. Take some time to look at how censuses are performed, who participates in them, and what they can learn from the data that is and is not collected. Refer to the online and poster map of Indigenous Languages in Canada featured in the 2017 November/December issue of Canadian Geographic, and explore how students feel about the number of speakers each language has and what the current data means for the people who speak each language. Additionally, look at the language families listed and the names of each language used by the federal government in collecting this data. Discuss with students why these may not be the correct names and how they can help in the reconciliation process by using the correct language names. LEARNING OUTCOMES: • Students will learn about the number and • Students will learn about the importance of diversity of languages and language groups language and the ties it has to culture. spoken by Indigenous Peoples in Canada. • Students will become engaged in learning a • Students will learn that Indigenous Peoples local Indigenous language. in Canada speak many languages and that some languages are endangered. INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES Foundational knowledge and perspectives FIRST NATIONS “One of the first acts of colonization and settlement “Our languages are central to our ceremonies, our rela- is to name the newly ‘discovered’ land in the lan- tionships to our lands, the animals, to each other, our guage of the colonizers or the ‘discoverers.’ This is understandings, of our worlds, including the natural done despite the fact that there are already names world, our stories and our laws.” for these places that were given by the original in- habitants. -

Obviation in Michif Deborah Weaver

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 8-1-1982 Obviation in Michif Deborah Weaver Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Weaver, Deborah, "Obviation in Michif" (1982). Theses and Dissertations. 672. https://commons.und.edu/theses/672 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OBVIATION IN MICHIF by Deborah Weaver Bachelor of Science, Wheaton College, 1976 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota August 1982 -s J 1 I This thesis submitted by Deborah Weaver in partial ful fillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota is hereby approved by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done. This thesis meets the standards for appearance and con forms to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of North Dakota, and is hereby ap proved . ( I W k i 11 Title OBVIATION IN MICHIF Department Linguistics Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the Uni versity of North Dakota, I agree that the Library of this University shall make it freely available for in spection. -

Fpcc-Newsletter-Spring-Summer-2014

first peoples’ news spring /summer 2014 first peoples’ cultural council IN THIS ISSUE New Museum Exhibition 2 New Arts Funding from FPCC Available for First Nations Youth SHOWCASING B.C.’S LIVING in B.C. FIRST NATIONS LANGUAGES 3 New Resources Available for First Nations Languages in B.C. Most people are unaware of the variety approaches with contemporary storytell- and richness of languages in this prov- ing. It will make use of audio and visual 4 FirstVoices Resources: Flash Card ince. With 34 Indigenous languages and media, artwork and narrative text in Eng- and Label Maker 61 dialects, B.C. is the most linguistically lish as well as First Nations languages. diverse region in Canada. Most importantly, it will demonstrate 4 Geek Alert! PC Keyboard In an inspiring new partnership, the the diversity and resilience of languages Software Update First Peoples’ Cultural Council (FPCC) in B.C. by showcasing languages by has been working with the Royal BC region as well as individual efforts to 5 Seabird Island Language Nests is Museum to create the innovative rejuvenate languages through hard work Engaging Young Language Learners Our Living Languages exhibition, which and perseverance. will provide an opportunity to celebrate “This is exciting for us and a progressive 6 Mentor-Apprentice Teams Creating these First Nations languages and the move on behalf of the Royal BC Museum,” a New Generation of Speakers people who are working to preserve says FPCC Chair Lorna Williams. “The and revitalize them. museum is a wonderful venue in which to 8 In Conversation with AADA Recipient The exhibition will fuse traditional share the stories and perspectives of First Kevin Loring Continued next page… 9 Upgrades to the FirstVoices Language Tutor Now Available to Communities 10 Community Success Story: SECWEPEMCTSÍN Language Tutor Lessons 11 FirstVoices Coordinator Peter Brand Retires…Or Does He? Our Living Languages: First Peoples' Voices in B.C. -

Grants and Contributions

TABLED DOCUMENT 287-18(3) TABLED ON NOVEMBER 1, 2018 Grants and Contributions Results Report 2017 – 2018 Subventions et Contributions Le present document contient la traduction française du résumé et du message du ministre Rapport 2017 – 2018 October 2018 | Octobre 2018 If you would like this information in another official language, call us. English Si vous voulez ces informations dans une autre langue officielle, contactez-nous. French Kīspin ki nitawihtīn ē nīhīyawihk ōma ācimōwin, tipwāsinān. Cree Tłı̨chǫ yatı k’ę̀ę̀. Dı wegodı newǫ dè, gots’o gonede. Tłı̨chǫ Ɂerıhtł’ıś Dëne Sųłıné yatı t’a huts’elkër xa beyáyatı theɂą ɂat’e, nuwe ts’ën yółtı. Chipewyan Edı gondı dehgáh got’ı̨e zhatıé k’ę́ę́ edatł’éh enahddhę nıde naxets’ę́ edahłı.́ South Slavey K’áhshó got’ı̨ne xǝdǝ k’é hederı ɂedı̨htl’é yerınıwę nı ́dé dúle. North Slavey Jii gwandak izhii ginjìk vat’atr’ijąhch’uu zhit yinohthan jì’, diits’àt ginohkhìi. Gwich’in Uvanittuaq ilitchurisukupku Inuvialuktun, ququaqluta. Inuvialuktun ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᑎᑎᕐᒃᑲᐃᑦ ᐱᔪᒪᒍᕕᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᓕᕐᒃᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ, ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐅᖄᓚᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᑎᑦ. Inuktitut Hapkua titiqqat pijumagupkit Inuinnaqtun, uvaptinnut hivajarlutit. Inuinnaqtun Indigenous Languages Secretariat: 867-767-9346 ext. 71037 Francophone Affairs Secretariat: 867-767-9343 TABLE OF CONTENTS MINISTER’S MESSAGE ............................................................. i MESSAGE DU MINISTRE .......................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................ 3 RÉSUMÉ ................................................................................. -

The Spirit and Intent of Treaty Eight: a Sagaw Eeniw Perspective

The Spirit and Intent of Treaty Eight: A Sagaw Eeniw Perspective A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for a Masters Degree in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sheldon Cardinal Fall 2001 © Copyright Sheldon Cardinal, 2001. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for a graduate degree from the University ofSaskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries ofthis University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying ofthis thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head ofthe Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use ofthis thesis orparts thereoffor financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use ofmaterial in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: The Dean, College ofLaw University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N5A6 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number ofpeople that I would like to thank for their assistance and guidance in completing my thesis. First, I would like to acknowledge my family. My parents, Harold and Maisie Cardinal have always stressed the importance ofeducation. -

Manitoba Postsecondary Graduates from the Class of 2000 : How Did They Fare? by Chantal Vaillancourt

Catalogue no. 81-595-MIE — No. 029 ISSN: 1711-831X ISBN: 0-662-40245-6 Research Paper Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics Manitoba postsecondary graduates from the Class of 2000 : how did they fare? by Chantal Vaillancourt Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics Division 2001 Main Building, Ottawa, K1A 0T6 Telephone: 1 800 307-3382 Fax: 1 613 951-9040 Statistics Statistique Canada Canada How to obtain more information Specific inquiries about this product and related statistics or services should be directed to: Client Services, Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0T6 (telephone: (613) 951-7608; toll free at 1 800 307-3382; by fax at (613) 951-9040; or e-mail: [email protected]). For information on the wide range of data available from Statistics Canada, you can contact us by calling one of our toll-free numbers. You can also contact us by e-mail or by visiting our website. National inquiries line 1 800 263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1 800 363-7629 Depository Services Program inquiries 1 800 700-1033 Fax line for Depository Services Program 1 800 889-9734 E-mail inquiries [email protected] Website www.statcan.ca Information to access the product This product, catalogue no. 81-595-MIE, is available for free. To obtain a single issue, visit our website at www.statcan.ca and select Our Products and Services. Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner and in the official language of their choice. -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-7 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9871-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5195 PRINT ISSN 1925-5209 WEB Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background. -

Aspect and the Chipewyan Verb

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1998 Aspect and the Chipewyan verb Bortolin, Leah Bortolin, L. (1998). Aspect and the Chipewyan verb (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/22542 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25896 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Aspect and the Chipewyan Verb by Leah Bortolin A THESIS SUBMI?TED TO THE FACULTÿ OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS CALGARY, ALBERTA February, 1998 O Leah Bortolin 1998 National Libmiy Bibiiothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disaibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fonne de microfiche/nim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions.