Ancient Knowledge of Ancient Sites: Tracing Dene Identity from the Late Pleistocene and Holocene Christopher C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Land Claims and the Future of Archaeology in the Northwest Territories, Canada Thomas D

17 Native Land Claims and the Future of Archaeology in the Northwest Territories, Canada Thomas D. Andrews Charles D. Arnnold Elisa J. Hart Margaret M. Bertulli The settlement of comprehensive land claims is ushering in major changes in the manage ment of land and resources in the Northwest Territories, including heritage resources. This chap ter summarizes the progress that has been made in completing land claims, anticipates the impact that the claims will have on the way archaeological research is conducted, and discusses how the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) is responding to these changes. Suggestions for dealing with the current social and political setting in the design and implementation of archaeological projects are also presented. OUTLINE OF NATIVE LAND CLAIMS IN THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES In the early 1970s, the Government of Canada established a comprehensive claims policy to guide negotiations with Native groups in settling Aboriginal interests in lands that they tradition ally occupied. Although the Northwest Territories has its own legislative assembly and its own bureaucracy to administer most of the business of government, the Government of Canada has the sole responsibility for settling Aboriginal land claims in the Northwest Territories. The Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Territories are the Inuit, the Dene, the Cree, and the Metis. The Inuit include the Inuvialuit of the Beaufort Sea and Amundson Gulf areas of the west ern Arctic, who, in 1984, were the first Aboriginal group in the Northwest Territories to settle a land claim with the Government of Canada (see Figure 1). In May, 1993, the Inuit of the eastern Arctic, an area commonly referred to as “Nunavut” signed a final agreement on a land claim. -

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Faculty of Humanities, Department of Linguistics and Faculty of Education, Indigenous Education Art Napoleon, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental Member iii ABstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental MemBer Through a review of literature and a qualitative inquiry of Cree language practitioners and knowledge keepers, this study explores traditional concepts related to Cree worldview specifically through the lens of nîhiyawîwin, the Cree language. Avoiding standard dictionary approaches to translations, it provides inside views and perspectives to provide broader translations of key terms related to Cree values and principles, Cree philosophy, Cree cosmology, Cree spirituality, and Cree ceremonialism. It argues the importance of providing connotative, denotative, implied meanings and etymology of key terms to broaden the understanding of nîhiyaw tâpisinowin and the need -

Northwest Territories Biodiversity Action Plan

Canada’s Northwest Territories Biodiversity Action Plan Prepared by: Jody Snortland, SRRB & Suzanne Carriere, GNWT WGRI-2 Meeting, Paris, France, 9-13 July 2007 Outline • Northwest Territories - Sahtu • Biodiversity in the NWT • Challenges and Opportunities • Action Planning • Implementation in the Sahtu Northwest Territories ‘Denendeh’ • 42,982 people • 1,171,918 km2 (= twice France) • 3.7 persons per 100 km2 • 5.3 caribou per 100 km2 Northwest Territories Languages • DENE (Chipewyan, Gwich’in, North Slavey, South Slavey, Tłįcho) • CREE • ENGLISH • INUIT/INUVIALUIT • FRANÇAIS (Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun) Land Claim Agreements Settled Land Claims • Inuvialuit – 1984 • Gwich’in – 1992 • Sahtu – 1993 •Tłįcho – 2005 Sahtu Settlement Area • 2629 people K'asho Got'ine District • 283,000 km2 Y# Colville Lake Y# • 1.0 person per Fort Good Hope 2 Deline District 100 km Y# Deline Norman Wells Y# Y# Tulita • Language: North Slavey Tulita District • ‘Sahtu’ means Great Bear Lake Biodiversity in the NWT • About 30,000 species • 75 mammals, 273 birds, 100 fish, 1107 plants Ecosystems in the NWT Dè = the land “All things infused with life, including rocks” • Large Lakes and Rivers • From Boreal Forest & Mountains to Tundra Mackenzie Delta Peary Caribou Northern Arctic Southern Arctic Mackenzie River ‘Deh Cho’ Taiga Plains Taiga Shield Taiga Cordillera Polar Bear Beaufort Sea Challenges Challenges & • Dual economy Opportunities • Increasing pressure • Outstanding Land Claims • Stressed capacity to adapt Opportunities • Vast and relatively -

Understanding Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Northwest Territories: Chapter 2: Early Treaty-Making in the NWT

Understanding Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Northwest Territories: Chapter 2: Early Treaty-making in the NWT he first chapter in this series, Understanding Aboriginal The Royal Proclamation Tand Treaty Rights in the NWT: An Introduction, touched After Great Britain defeated France for control of North briefly on Aboriginal and treaty rights in the NWT. This America, the British understood the importance of chapter looks at the first contact between Aboriginal maintaining peace and good relations with Aboriginal peoples and Europeans. The events relating to this initial peoples. That meant setting out rules about land use contact ultimately shaped early treaty-making in the NWT. and Aboriginal rights. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 Early Contact is the most important statement of British policy towards Aboriginal peoples in North America. The Royal When European explorers set foot in North America Proclamation called for friendly relations with Aboriginal they claimed the land for the European colonial powers peoples and noted that “great frauds and abuses” had they represented. This amounted to European countries occurred in land dealings. The Royal Proclamation also asserting sovereignty over North America. But, in practice, said that only the Crown could legally buy Aboriginal their power was built up over time by settlement, trade, land and any sale had to be made at a “public meeting or warfare, and diplomacy. Diplomacy in these days included assembly of the said Indians to be held for that purpose.” entering into treaties with the indigenous Aboriginal peoples of what would become Canada. Some of the early treaty documents aimed for “peace and friendship” and refer to Aboriginal peoples as “allies” rather than “subjects”, which suggests that these treaties could be interpreted as nation-to-nation agreements. -

Indigenous Languages

INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES PRE-TEACH/PRE-ACTIVITY Have students look at the Indigenous languages and/or language groups that are displayed on the map. Discuss where this data came from (the 2016 census) and what biases or problems this data may have, such as the fear of self-identifying based on historical reasons or current gaps in data. Take some time to look at how censuses are performed, who participates in them, and what they can learn from the data that is and is not collected. Refer to the online and poster map of Indigenous Languages in Canada featured in the 2017 November/December issue of Canadian Geographic, and explore how students feel about the number of speakers each language has and what the current data means for the people who speak each language. Additionally, look at the language families listed and the names of each language used by the federal government in collecting this data. Discuss with students why these may not be the correct names and how they can help in the reconciliation process by using the correct language names. LEARNING OUTCOMES: • Students will learn about the number and • Students will learn about the importance of diversity of languages and language groups language and the ties it has to culture. spoken by Indigenous Peoples in Canada. • Students will become engaged in learning a • Students will learn that Indigenous Peoples local Indigenous language. in Canada speak many languages and that some languages are endangered. INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES Foundational knowledge and perspectives FIRST NATIONS “One of the first acts of colonization and settlement “Our languages are central to our ceremonies, our rela- is to name the newly ‘discovered’ land in the lan- tionships to our lands, the animals, to each other, our guage of the colonizers or the ‘discoverers.’ This is understandings, of our worlds, including the natural done despite the fact that there are already names world, our stories and our laws.” for these places that were given by the original in- habitants. -

Ridington-Dane-Zaa Digital Archive Repatriation Project

Contract Position Description December 10, 2020 Position Title Archival Assistant – Ridington-Dane-zaa Digital Archive Repatriation Project Project Background The Ridington-Dane-zaa Digital Archive (RDA) project is a collaborative digital repatriation initiative between: • The Ridington family ethnographers and their Dane-zaa heritage collection(s)i, • The Dane-zaa (Dene peoples indigenous to the Peace River region) communities whose culture is documented by the Ridington Collection: o Blueberry River First Nation o Doig River First Nation o Halfway River First Nation o Prophet River First Nation • University & industry partners including: o UBC CEDaR Lab as interim platform/portal host and steward o BC Hydro as community archive capacity development funder o Nation Governance Initiative, grant issued to Doig River First Nation by New Relationship Trust to help define Athabaskan / Dane-zaa specific protocols for stewardship including access, use, attribution and sharing (2020-2021) https://www.newrelationshiptrust.ca/funding/nation-governance/ o (potentially) UNBC as interim archival storage for physical master materials. Place for final storage to be determined. Options being explored at this time include: § Tse Kwą̂ Heritage Centre at Charlie Lake, BC § Dene Heritage Centre (in proposal/development stage for Indigenous communities of the Peace River Region) Goal The goal of this project is to digitally archive and catalog the entire Ridington collection so that it can be returned (repatriated) to communities for their use and stewardship. Ridington-Dane-zaa Collection History The Ridington Collection of Dane-zaa audio recordings, images, video recordings, and texts began in 1964 after Robin Ridington and Antonia Mills (Antonia Ridington at the time) had met at Harvard University in 1963 as students, married, and began their field work with the Dane-zaa. -

Environment and Natural Nt and Natural Resources

ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Implementation Plan for the Action Plan for Boreal Woodland Caribou in the Northwest Territories: 2010-2015 The Action Plan for Boreal Woodland Caribou Conservation in the Northwest Territories was released after consulting with Management Authorities, Aboriginal organizations, communities, and interested stakeholders. This Implementation Plan is the next step of the Action Plan and will be used by Environment and Natural Resources to implement the actions in cooperation with the Tᰯch Government, Wildlife Management Boards and other stakeholders. In the future, annual status reports will be provided detailing the progress of the actions undertaken and implemented by Environment and Natural Resources. Implementation of these 21 actions will contribute to the national recovery effort for boreal woodland caribou under the federal Species at Risk Act . Implementation of certain actions will be coordinated with Alberta as part of our mutual obligations outlined in the signed Memorandum of Understanding for Cooperation on Managing Shared Boreal Populations of Woodland Caribou. This MOU acknowledges boreal caribou are a species at risk that are shared across jurisdictional lines and require co-operative management. J. Michael Miltenberger Minister Environment and Natural Resources IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Environment and Natural Resources Boreal Woodland Caribou Conservation in the Northwest Territories 2010–2015 July 2010 1 Headquarters Inuvik Sahtu North Slave Dehcho South Slave Action Initiative Involvement Region Region Region Region Region 1 Prepare and implement Co-lead the Dehcho Not currently Currently not Not currently To be developed To be developed comprehensive boreal caribou Boreal Caribou Working needed. needed. needed. by the Dehcho by the Dehcho range management plans in Group. -

Mackenzie Highway Extension, for Structuring EIA Related Field Investigations and for Comparative Assessment of Alternate Routes

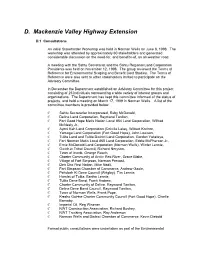

D. Mackenzie Valley Highway Extension D.1 Consultations An initial Stakeholder Workshop was held in Norman Wells on June 8, 1998. The workshop was attended by approximately 60 stakeholders and generated considerable discussion on the need-for, and benefits-of, an all-weather road. A meeting with the Sahtu Secretariat and the Sahtu Regional Land Corporation Presidents was held on November 12, 1998. The group reviewed the Terms of Reference for Environmental Scoping and Benefit Cost Studies. The Terms of Reference were also sent to other stakeholders invited to participate on the Advisory Committee. In December the Department established an Advisory Committee for this project consisting of 25 individuals representing a wide variety of interest groups and organizations. The Department has kept this committee informed of the status of projects, and held a meeting on March 17, 1999 in Norman Wells. A list of the committee members is provided below. C Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated, Ruby McDonald, C Deline Land Corporation, Raymond Taniton, C Fort Good Hope Metis Nation Local #54 Land Corporation, Wilfred McNeely Jr., C Ayoni Keh Land Corporation (Colville Lake), Wilbert Kochon, C Yamoga Land Corporation (Fort Good Hope), John Louison, C Tulita Land and Tulita District Land Corporation, Gordon Yakeleya, C Fort Norman Metis Local #60 Land Corporation, Eddie McPherson Jr., C Ernie McDonald Land Corporation (Norman Wells), Winter Lennie, C Gwich=in Tribal Council, Richard Nerysoo, C Town of Inuvik, George Roach, C Charter Community of Arctic Red -

The Spirit and Intent of Treaty Eight: a Sagaw Eeniw Perspective

The Spirit and Intent of Treaty Eight: A Sagaw Eeniw Perspective A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for a Masters Degree in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sheldon Cardinal Fall 2001 © Copyright Sheldon Cardinal, 2001. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for a graduate degree from the University ofSaskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries ofthis University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying ofthis thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head ofthe Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use ofthis thesis orparts thereoffor financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use ofmaterial in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: The Dean, College ofLaw University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N5A6 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number ofpeople that I would like to thank for their assistance and guidance in completing my thesis. First, I would like to acknowledge my family. My parents, Harold and Maisie Cardinal have always stressed the importance ofeducation. -

1998-1999 Sahtu Dene and Metis Comprehensive Land Claim

Foreword The Implementation Committee is pleased to provide its fifth annual report on the implementation of the Sahtu Dene and Metis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement. The report covers the fiscal year extending from April 1, 1998 to March 31, 1999. The Implementation Committee is composed of a senior official from each of the parties: the Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated, the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Government of Canada. It functions by consensus and serves as a forum where parties can raise issues and voice their concerns. The role of the Implementation Committee is to oversee, direct and monitor the implementation of the Agreement. This annual report describes achievements and developments during the year. Information is contributed by various federal and territorial departments, The Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated and other bodies established under the Agreement. We are committed to strengthening the partnerships that are key to the successful implementation of this Agreement. Our achievements to date are the product of partners working together to recognize Aboriginal rights in an atmosphere of mutual respect, and the commitment of the parties to fulfil obligations pursuant to this Agreement. Danny Yakeleya Mark Warren Leigh Jessen Sahtu Secretariat Government of the Government of Incorporated Northwest Territories Canada v Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................... v Glossary of Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................... viii -

LANGUAGES of the LAND a RESOURCE MANUAL for ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS

LANGUAGES of THE LAND A RESOURCE MANUAL FOR ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS Prepared by: Crosscurrent Associates, Hay River Prepared for: NWT Literacy Council, Yellowknife TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Remarks - NWT Literacy Council . 2 Definitions . 3 Using the Manual . 4 Statements by Aboriginal Language Activists . 5 Things You Need to Know . 9 The Importance of Language . 9 Language Shift. 10 Community Mobilization . 11 Language Assessment. 11 The Status of Aboriginal Languages in the NWT. 13 Chipewyan . 14 Cree . 15 Dogrib . 16 Gwich'in. 17 Inuvialuktun . 18 South Slavey . 19 North Slavey . 20 Aboriginal Language Rights . 21 Taking Action . 23 An Overview of Aboriginal Language Strategies . 23 A Four-Step Approach to Language Retention . 28 Forming a Core Group . 29 Strategic Planning. 30 Setting Realistic Language Goals . 30 Strategic Approaches . 31 Strategic Planning Steps and Questions. 34 Building Community Support and Alliances . 36 Overcoming Common Language Myths . 37 Managing and Coordinating Language Activities . 40 Aboriginal Language Resources . 41 Funding . 41 Language Resources / Agencies . 43 Bibliography . 48 NWT Literacy Council Languages of the Land 1 LANGUAGES of THE LAND A RESOURCE MANUAL FOR ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS We gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance received from the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Education, Culture and Employment Copyright: NWT Literacy Council, Yellowknife, 1999 Although this manual is copyrighted by the NWT Literacy Council, non-profit organizations have permission to use it for language retention and revitalization purposes. Office of the Languages Commissioner of the Northwest Territories Cover Photo: Ingrid Kritch, Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute INTRODUCTORY REMARKS - NWT LITERACY COUNCIL The NWT Literacy Council is a territorial-wide organization that supports and promotes literacy in all official languages of the NWT. -

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3427 L2/08-132

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3427 L2/08-132 2008-04-08 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode 39 Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics in the UCS Source: Michael Everson and Chris Harvey Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2008-04-08 1. Summary. This document requests 39 additional characters to be added to the UCS and contains the proposal summary form. 1. Syllabics hyphen (U+1400). Many Aboriginal Canadian languages use the character U+1428 CANADIAN SYLLABICS FINAL SHORT HORIZONTAL STROKE, which looks like the Latin script hyphen. Algonquian languages like western dialects of Cree, Oji-Cree, western and northern dialects of Ojibway employ this character to represent /tʃ/, /c/, or /j/, as in Plains Cree ᐊᓄᐦᐨ /anohc/ ‘today’. In Athabaskan languages, like Chipewyan, the sound is /d/ or an alveolar onset, as in Sayisi Dene ᐨᕦᐣᐨᕤ /t’ąt’ú/ ‘how’. To avoid ambiguity between this character and a line-breaking hyphen, a SYLLABICS HYPHEN was developed which resembles an equals sign. Depending on the typeface, the width of the syllabics hyphen can range from a short ᐀ to a much longer ᐀. This hyphen is line-breaking punctuation, and should not be confused with the Blackfoot syllable internal-w final proposed for U+167F. See Figures 1 and 2. 2. DHW- additions for Woods Cree (U+1677..U+167D). ᙷᙸᙹᙺᙻᙼᙽ/ðwē/ /ðwi/ /ðwī/ /ðwo/ /ðwō/ /ðwa/ /ðwā/. The basic syllable structure in Cree is (C)(w)V(C)(C).