The Deseret Alphabet As Contrasted with Other Spelling Reforms in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hebrew Alphabet

BBH2 Textbook Supplement Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1 The following comments explain, provide mnemonics for, answer questions that students have raised about, and otherwise supplement the second edition of Basics of Biblical Hebrew by Pratico and Van Pelt. Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1.1 The consonants For begadkephat letters (§1.5), the pronunciation in §1.1 is the pronunciation with the Dagesh Lene (§1.5), even though the Dagesh Lene is not shown in §1.1. .Kaf” has an “off” sound“ כ The name It looks like open mouth coughing or a cup of coffee on its side. .Qof” is pronounced with either an “oh” sound or an “oo” sound“ ק The name It has a circle (like the letter “o” inside it). Also, it is transliterated with the letter q, and it looks like a backwards q. here are different wa s of spellin the na es of letters. lef leph leˉ There are many different ways to write the consonants. See below (page 3) for a table of examples. See my chapter 1 overheads for suggested letter shapes, stroke order, and the keys to distinguishing similar-looking letters. ”.having its dot on the left: “Sin is never ri ht ׂש Mnemonic for Sin ׁש and Shin ׂש Order of Sin ׁש before Shin ׂש Our textbook and Biblical Hebrew lexicons put Sin Some alphabet songs on YouTube reverse the order of Sin and Shin. Modern Hebrew dictionaries, the acrostic poems in the Bible, and ancient abecedaries (inscriptions in which someone wrote the alphabet) all treat Sin and Shin as the same letter. -

PARK JIN HYOK, Also Known As ("Aka") "Jin Hyok Park," Aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case Fl·J 18 - 1 4 79

AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the RLED Central District of California CLERK U.S. DIS RICT United States ofAmerica JUN - 8 ?018 [ --- .. ~- ·~".... ~-~,..,. v. CENT\:y'\ l i\:,: ffl1G1 OF__ CAUFORN! BY .·-. ....-~- - ____D=E--..... PARK JIN HYOK, also known as ("aka") "Jin Hyok Park," aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case fl·J 18 - 1 4 79 Defendant. CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best ofmy knowledge and belief. Beginning no later than September 2, 2014 and continuing through at least August 3, 2017, in the county ofLos Angeles in the Central District of California, the defendant violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 371 Conspiracy 18 u.s.c. § 1349 Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud This criminal complaint is based on these facts: Please see attached affidavit. IBJ Continued on the attached sheet. Isl Complainant's signature Nathan P. Shields, Special Agent, FBI Printed name and title Sworn to before ~e and signed in my presence. Date: ROZELLA A OLIVER Judge's signature City and state: Los Angeles, California Hon. Rozella A. Oliver, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title -:"'~~ ,4G'L--- A-SA AUSAs: Stephanie S. Christensen, x3756; Anthony J. Lewis, x1786; & Anil J. Antony, x6579 REC: Detention Contents I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 II. PURPOSE OF AFFIDAVIT ......................................................................1 III. SUMMARY................................................................................................3 -

“To Every Nation, Kindred, Tongue, and People”

12 “To Every Nation, Kindred, Tongue, and People” Po Nien (Felipe) Chou and Petra Chou Po Nien (Felipe) Chou is a religious educator and manager of the Offi ce of Research for the Seminaries and Institutes (S&I) of Th e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Petra Chou is a homemaker and teaches in the Chinese Immersion program for the Alpine School District. he Book of Mormon was fi rst translated into the English language by Tthe Prophet Joseph Smith in 1829. Th e goal is now to make it avail- able “to every nation, kindred, tongue, and people” (Mosiah 15:28). Th is chapter explores the eff orts of Th e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to bring forth the Book of Mormon in other languages and to make it accessible to all the world. Although it will not provide an exhaustive review of all 110 translations (87 full book and 23 selections)1 distributed by the Church by spring 2015, it will examine a number of translations, versions, and editions, along with the eff orts to bring forth this sacred volume to “all nations, kindreds, tongues and people” (D&C 42:58). Ancient prophets declared that in the latter days the Lord would “com- mence his work among all nations, kindreds, tongues, and people, to bring about the restoration of his people upon the earth” (2 Nephi 30:8). Th e Book of Mormon was to “be kept and preserved” so that the knowledge of the Savior and his gospel would go forth and be taught unto “every nation, kindred, tongue, and people” in preparation for the Second Coming of the 228 Po Nien (Felipe) Chou and Petra Chou Lord (see 1 Nephi 13:40; Mosiah 3:20; Alma 37:4; D&C 42:48; D&C 133:37). -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

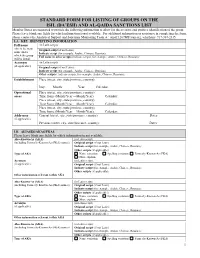

Standard Form for Listing of Groups on the Isil (Da'esh) and Al-Qaida

STANDARD FORM FOR LISTING OF GROUPS ON THE ISIL (DA’ESH) AND AL-QAIDA SANCTIONS LIST Member States are requested to provide the following information to allow for the accurate and positive identification of the group. Please leave blank any fields for which information is not available. For additional information or assistance in completing the form, please contact the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team at : email:[email protected], telephone: 917-367-2315. I.A. KEY IDENTIFYING INFORMATION Full name (in Latin script) (this is the main Original script (if not Latin): name under Indicate script (for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): which the group Full name in other scripts (indicate scripts, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): will be listed) Acronym (in Latin script) (if applicable) Original script (if not Latin): Indicate script (for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): Other scripts ( indicate scripts, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): Establishment Place (street, city, state/province, country): Day: Month: Year: Calendar: Operational Place (street, city, state/province, country): areas Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Place (street, city, state/province, country): Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Place (street, city, state/province, country): Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Addresses Current (street, city, state/province, country): Dates: (if applicable) Previous (street, city, state/province, country): Dates: I.B. ALIASES/AKAS/FKAS Please leave blank any fields for which -

ESH Affiliation and Association Letter and Documents

President Prof. Josep Redon Internal Medicine Hospital Clinico University of Valencia Avda Blasco Ibanez, 17 To Phone: +34 96 3862647 Fax: +34 96 3862647 Presidents of National Societies of Hypertension e-mail: [email protected] Dear President, Vice President Prof Anna F. Dominiczak The European Society of Hypertension (ESH) has the commitment to establish a Regius Professor of Medicine and stable and organised European platform for scientific exchange in hypertension Head of College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences aiming to improve not only the quality of research but also to increase knowledge University of Glasgow of hypertension and vascular risk all over Europe. Advances in the knowledge of Wolfson Medical School Building University Avenue hypertension and vascular care as well as improvements in prevention and Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK clinical care, contribute to reduce hypertension-associated morbidity and Phone: 0141 330 2738 Fax: 0141 330 5339 mortality across Europe. [email protected] Over the last few years, ESH has been expanding in memberships and activities Officer at Large including organisation of congresses, endorsement of congresses and other Prof. Margus Viigimaa Centre of Cardiology meetings, and organisation of a number of educational activities, including North Estonia Medical Centre summer schools and advanced courses. Involvement of the National Sutiste St. 19 Hypertension Societies in Europe has always been the main purpose for the ESH Tallin 13419, Estonia Phone: +372 511 0070 Scientific Council. Fax: +372 697 1415 [email protected] The relationship between ESH and the National Societies has developed very Secretary well over the years and is expected to develop further. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

A History of the Deseret Alphabet

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1970 A History of the Deseret Alphabet Larry Ray Wintersteen Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wintersteen, Larry Ray, "A History of the Deseret Alphabet" (1970). Theses and Dissertations. 5220. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5220 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A A HISTORY OF THE DESERET ALPHABET A A thesis presented to the department of speech and dramatic arts brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by larry ray wintersteen may 1970 A HISTORY OF THE DESERET ALPHABET larry ray wintersteen department of speech and dramatic arts MA degree may 1970 ABSTRACT L the church of jesus chrichristst of latter day saints during the years 185218771852 1877 introduced to its membership a form of rhetoric writing system called the deseret alphabet phonetic alphabet this experi- ment was intended to alleviate the problem of non-noncommunicationcommunication which was created by the great influx of foreign speaking saints into the great salt lake valley the alphabet was developed and encouraged -

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters Version 2.06, October 31, 2014 Pim Rietbroek Preamble Few typefaces – if any – allow the user to access every Latin character, every IPA character, every diacritic, and to have these combine in a typographically satisfactory manner, in a range of styles (roman, italic, and more); even fewer add full support for Greek, both modern and ancient, with specialised characters that papyrologists and epigraphers need; not to mention coverage of the Slavic languages in the Cyrillic range. The Brill typeface aims to do just that, and to be a tool for all scholars in the humanities; for Brill’s authors and editors; for Brill’s staff and service providers; and finally, for anyone in need of this tool, as long as it is not used for any commercial gain.* There are several fonts in different styles, each of which has the same set of characters as all the others. The Unicode Standard is rigorously adhered to: there is no dependence on the Private Use Area (PUA), as it happens frequently in other fonts with regard to characters carrying rare diacritics or combinations of diacritics. Instead, all alphabetic characters can carry any diacritic or combination of diacritics, even stacked, with automatic correct positioning. This is made possible by the inclusion of all of Unicode’s combining characters and by the application of extensive OpenType Glyph Positioning programming. Credits The Brill fonts are an original design by John Hudson of Tiro Typeworks. Alice Savoie contributed to Brill bold and bold italic. The black-letter (‘Fraktur’) range of characters was made by Karsten Lücke. -

How Children Learn to Write Words

How Children Learn to Write Words How Children Learn to Write Words Rebecca TReiman and bReTT KessleR 1 3 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. A copy of this book’s Catalog-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–990797–7 -

Proposed ALA-LC Romanization Table for the Deseret Alphabet October 27, 2015

Proposed ALA-LC Romanization Table for the Deseret Alphabet October 27, 2015 Background The Deseret alphabet is a phonetic alphabet developed in Utah Territory in the 19th century, under the direction of Brigham Young. Only four books were published in the Deseret alphabet in Brigham Young’s lifetime. After his death, the alphabet fell into obscurity. In the last few years, there has been a renewed interest in the alphabet as a historical curiosity, following the alphabet’s 2001 addition to the Unicode standard, filling blocks 10400 through 1044F. Due to advances in self-publishing, it has become possible for hobbyists to publish new works in the Deseret alphabet. To date we are aware of 34 recently published volumes, as well as some ephemera such as newsletters. Because the Deseret alphabet has ties to the Mormon movement and to Utah history, it is of interest to the special collections department at Brigham Young University’s Harold B. Lee Library, which collects extensively in areas related to Mormonism and Western history. Methodology After creating and then refining several versions of the romanization standard on my own, I reached out to Dirk Elzinga, a linguistics professor at Brigham Young University who recently co-authored a book on the history of the Deseret alphabet. Dr. Elzinga offered helpful feedback in approaching the romanization project, particularly in the case of how to best romanize the Deseret alphabet vowels. In creating the romanization standard, we have tried to follow the Procedural Guidelines for Proposed New or Revised Romanization Tables as closely as possible, although it has sometimes been challenging to apply them to an alphabet of this type. -

Acquisition Hierarchy of Korean As a Foreign Language

UNIVERSITY OF HAVVAI'I LIBRARY ACQUISITION HIERARCHY OF KOREAN AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PIDLOSOPHY IN EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES (KOREAN) DECEMBER 2002 By Jiha Hwang Dissertation Connnittee: Ho-min Sohn, Chairperson David Ashworth James D. Brown Michael Forman Dong Jae Lee © Copyright 2002 by JihaHwang ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout my studies at the University of Hawai'i, I benefited immensely from stimulation provided by the faculty and students, not only in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, but also in the Department of Second Language Studies and the Department ofLinguistics. To all ofthem, I would like to say a collective thank you. There are a few people to whom I would like to express particular gratitude, however. To Dr. Ho Min Sohn, who not only served as my dissertation advisor, but who has been a valuable mentor and a source ofpsychological support throughout my doctoral program and while I was completing the dissertation. To Dr. Dong Jae Lee, whose warm heart, good advice and ceaseless efforts on behalf of students has not only been of great personal support to me, but a source of inspiration in my own professional development and a model which I hope to emulate. To Marilyn Plumlee, without whose help this dissertation would not be here. She was not merely an English proofreader. As a colleague and as a friend, she constantly raised highly provocative questions which helped me to think over again and again what I was trying to do.