Acquisition Hierarchy of Korean As a Foreign Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hebrew Alphabet

BBH2 Textbook Supplement Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1 The following comments explain, provide mnemonics for, answer questions that students have raised about, and otherwise supplement the second edition of Basics of Biblical Hebrew by Pratico and Van Pelt. Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1.1 The consonants For begadkephat letters (§1.5), the pronunciation in §1.1 is the pronunciation with the Dagesh Lene (§1.5), even though the Dagesh Lene is not shown in §1.1. .Kaf” has an “off” sound“ כ The name It looks like open mouth coughing or a cup of coffee on its side. .Qof” is pronounced with either an “oh” sound or an “oo” sound“ ק The name It has a circle (like the letter “o” inside it). Also, it is transliterated with the letter q, and it looks like a backwards q. here are different wa s of spellin the na es of letters. lef leph leˉ There are many different ways to write the consonants. See below (page 3) for a table of examples. See my chapter 1 overheads for suggested letter shapes, stroke order, and the keys to distinguishing similar-looking letters. ”.having its dot on the left: “Sin is never ri ht ׂש Mnemonic for Sin ׁש and Shin ׂש Order of Sin ׁש before Shin ׂש Our textbook and Biblical Hebrew lexicons put Sin Some alphabet songs on YouTube reverse the order of Sin and Shin. Modern Hebrew dictionaries, the acrostic poems in the Bible, and ancient abecedaries (inscriptions in which someone wrote the alphabet) all treat Sin and Shin as the same letter. -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

PARK JIN HYOK, Also Known As ("Aka") "Jin Hyok Park," Aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case Fl·J 18 - 1 4 79

AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the RLED Central District of California CLERK U.S. DIS RICT United States ofAmerica JUN - 8 ?018 [ --- .. ~- ·~".... ~-~,..,. v. CENT\:y'\ l i\:,: ffl1G1 OF__ CAUFORN! BY .·-. ....-~- - ____D=E--..... PARK JIN HYOK, also known as ("aka") "Jin Hyok Park," aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case fl·J 18 - 1 4 79 Defendant. CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best ofmy knowledge and belief. Beginning no later than September 2, 2014 and continuing through at least August 3, 2017, in the county ofLos Angeles in the Central District of California, the defendant violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 371 Conspiracy 18 u.s.c. § 1349 Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud This criminal complaint is based on these facts: Please see attached affidavit. IBJ Continued on the attached sheet. Isl Complainant's signature Nathan P. Shields, Special Agent, FBI Printed name and title Sworn to before ~e and signed in my presence. Date: ROZELLA A OLIVER Judge's signature City and state: Los Angeles, California Hon. Rozella A. Oliver, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title -:"'~~ ,4G'L--- A-SA AUSAs: Stephanie S. Christensen, x3756; Anthony J. Lewis, x1786; & Anil J. Antony, x6579 REC: Detention Contents I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 II. PURPOSE OF AFFIDAVIT ......................................................................1 III. SUMMARY................................................................................................3 -

Strangers at Home: North Koreans in the South

STRANGERS AT HOME: NORTH KOREANS IN THE SOUTH Asia Report N°208 – 14 July 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. CHANGING POLICIES TOWARDS DEFECTORS ................................................... 2 III. LESSONS FROM KOREAN HISTORY ........................................................................ 5 A. COLD WAR USES AND ABUSES .................................................................................................... 5 B. CHANGING GOVERNMENT ATTITUDES ......................................................................................... 8 C. A CHANGING NATION .................................................................................................................. 9 IV. THE PROBLEMS DEFECTORS FACE ...................................................................... 11 A. HEALTH ..................................................................................................................................... 11 1. Mental health ............................................................................................................................. 11 2. Physical health ........................................................................................................................... 12 B. LIVELIHOODS ............................................................................................................................ -

Cultural Heritage in Korea – from a Japanese Perspective Toshio Asakura National Museum of Ethnology

Cultural heritage in Korea – from a Japanese perspective Toshio Asakura National Museum of Ethnology Introduction The Korean television drama Dae Jang-geum has been popular not only in Korea but also throughout East Asia, including in Japan, Taiwan and China. It is based on the true story of Jang-geum, the reputedly first woman to hold the position of royal physician in the 16th-century during the Joseon Dynasty (1392−1897). What is interesting about the drama from a perspective of cultural her- itage is that it serves to highlight traditional Korean culture, espe- cially Korean court cuisine and medicine. How to cite this book chapter: Asakura, T 2016 Cultural heritage in Korea – from a Japanese perspective. In: Matsuda, A and Mengoni, L E (eds.) Reconsidering Cultural Heritage in East Asia, Pp. 103–119. London: Ubiquity Press. DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.5334/baz.f. License: CC-BY 4.0 104 Reconsidering Cultural Heritage in East Asia I was in charge of supervising the Japanese-language version of this show, and one of the most challenging, yet interesting, aspects of my task was to work out how to translate Korean culture to a Japanese audience.1 By referring to this drama, which was part of the so-called ‘Korean wave’ (hanryû), I will investigate the circum- stances surrounding three aspects of cultural heritage in Korea: culinary culture; Living National Treasures (i.e. holders of Impor- tant Intangible Cultural Properties); and cultural landscapes. Japan and Korea are said to share broadly similar cultural heritage, including amongst other things the influence of Chinese culture, as exemplified by the spoken language and script, and the influence of Confucianism. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

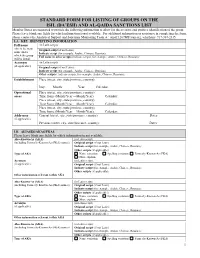

Standard Form for Listing of Groups on the Isil (Da'esh) and Al-Qaida

STANDARD FORM FOR LISTING OF GROUPS ON THE ISIL (DA’ESH) AND AL-QAIDA SANCTIONS LIST Member States are requested to provide the following information to allow for the accurate and positive identification of the group. Please leave blank any fields for which information is not available. For additional information or assistance in completing the form, please contact the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team at : email:[email protected], telephone: 917-367-2315. I.A. KEY IDENTIFYING INFORMATION Full name (in Latin script) (this is the main Original script (if not Latin): name under Indicate script (for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): which the group Full name in other scripts (indicate scripts, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): will be listed) Acronym (in Latin script) (if applicable) Original script (if not Latin): Indicate script (for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): Other scripts ( indicate scripts, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): Establishment Place (street, city, state/province, country): Day: Month: Year: Calendar: Operational Place (street, city, state/province, country): areas Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Place (street, city, state/province, country): Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Place (street, city, state/province, country): Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Addresses Current (street, city, state/province, country): Dates: (if applicable) Previous (street, city, state/province, country): Dates: I.B. ALIASES/AKAS/FKAS Please leave blank any fields for which -

ESH Affiliation and Association Letter and Documents

President Prof. Josep Redon Internal Medicine Hospital Clinico University of Valencia Avda Blasco Ibanez, 17 To Phone: +34 96 3862647 Fax: +34 96 3862647 Presidents of National Societies of Hypertension e-mail: [email protected] Dear President, Vice President Prof Anna F. Dominiczak The European Society of Hypertension (ESH) has the commitment to establish a Regius Professor of Medicine and stable and organised European platform for scientific exchange in hypertension Head of College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences aiming to improve not only the quality of research but also to increase knowledge University of Glasgow of hypertension and vascular risk all over Europe. Advances in the knowledge of Wolfson Medical School Building University Avenue hypertension and vascular care as well as improvements in prevention and Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK clinical care, contribute to reduce hypertension-associated morbidity and Phone: 0141 330 2738 Fax: 0141 330 5339 mortality across Europe. [email protected] Over the last few years, ESH has been expanding in memberships and activities Officer at Large including organisation of congresses, endorsement of congresses and other Prof. Margus Viigimaa Centre of Cardiology meetings, and organisation of a number of educational activities, including North Estonia Medical Centre summer schools and advanced courses. Involvement of the National Sutiste St. 19 Hypertension Societies in Europe has always been the main purpose for the ESH Tallin 13419, Estonia Phone: +372 511 0070 Scientific Council. Fax: +372 697 1415 [email protected] The relationship between ESH and the National Societies has developed very Secretary well over the years and is expected to develop further. -

Child Labor in the DPRK, Education and Indoctrination

Child Labor in the DPRK, Education and Indoctrination UNCRC Alternative Report to the 5th Periodic Report for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) September 2017 Submitted by People for Successful COrean REunification (PSCORE) Table of Contents Summary/Objective 2 Methodology 3 “Free” Education 4 Unchecked and Unmonitored: Physical Abuse in Schools 6 Forced Manual Labor during School 7 Mandatory Collections 8 Ideology and Education 9 Recommendation 12 References 13 1 Summary/Objective The goal of this report is for the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child to strongly consider the DPRK’s deplorable educational system at the 76th Pre-Sessional Working Group. A great number of reprehensible offenses have been committed by the DPRK against children’s education. Falsely advertised “free” education, unchecked corporal punishment and abuse in school, and forced manual labor in place of time in the classroom are the most notable, and will all be detailed in this report. But the most severe injustice is the content of the DPRK’s education, which is all geared to either overtly or covertly instill fear and hate into the minds of the state’s youngest and most impressionable minds. Education in the DPRK is filled with historical distortion and manipulative teachings that serve the state’s rulers, instilling a reverence for the DPRK’s government and leaders and a hatred toward any people or ideas that are not in alignment with the government’s. Education should be truthful and promote the values of peace, tolerance, equality, and understanding (General Comment No. 1, Article 29). -

£SOUTH KOREA @Imprisoned Writer Hwang Sok-Yong

£SOUTH KOREA @Imprisoned writer Hwang Sok-yong Hwang Sok-yong, a 50-year-old writer from South Korea, is one of many prisoners who have been arrested and imprisoned under the National Security Law for the peaceful exercise of their rights to freedom of expression and association. Amnesty International has adopted him as a prisoner of conscience and his calling for his immediate and unconditional release. Amnesty International has long campaigned for the amendment of the National Security Law which punishes "anti-state" (pro-North Korean) activities. The loose definition of "anti-state" activities and other provisions of this law means that it may easily be abused by the authorities. In fact, it has been often used to imprison people who visited North Korea without government permission or met north Koreans or alleged agents abroad, people who held socialist views or whose views were considered similar to those of the North Korean Government. Background about Hwang Sok-yong Hwang Sok-yong is a well-known and popular writer who has written over 20 novels and essays. Many have been translated and published in Japan, China, Germany and France and two have also been published in North Korea. His best-known work is a 10 volume epic called Jangkilsan which was completed in 1984. It has sold over three million copies in South Korea and remains a best seller today. Hwang Sok-yong has written numerous short stories and essays including The Shadow of Arms (on the Vietnam War) and Strange Land (an anthology of short works). He has received several literary awards. -

Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

The Korea Association of Teachers of English 2014 International Conference Making Connections in ELT : Form, Meaning, and Functions July 4 (Friday) - July 5 (Saturday), 2014 Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea Hosted by Seoul National University Organized by The Korea Association of Teachers of English Department of English, Seoul National University Sponsored by The National Research Foundation of Korea Seoul National University Korea Institute for Curriculum and Evaluation British Council Korea Embassy of the United States International Communication Foundation CHUNGDAHM Learning English Mou Mou Hyundae Yong-O-Sa Daekyo ETS Global Neungyule Education Cambridge University Press YBM Sisa This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government. 2014 KATE International Conference KATE Executive Board July 2012 - June 2014 President Junil Oh (Pukyong Nationa University) Vice Presidents - Journal Editing & Publication Jeongwon Lee (Chungnam National Univ) - Planning & Coordination Hae-Dong Kim (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies) - Research & Development Yong-Yae Park (Seoul National University) - Public Relations Seongwon Lee (Gyeonsang National University) - International Affairs & Information Jeongsoon Joh (Konkuk University) Secretary Generals Hee-Kyung Lee (Yonsei University) Hyunsook Yoon (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies) Treasurer Yunkyoung Cho (Pukyong National University) International Affairs Officers Hikyoung Lee (Korea University) Isaiah WonHo Yoo (Sogang University) -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6