Old Italic Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hebrew Alphabet

BBH2 Textbook Supplement Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1 The following comments explain, provide mnemonics for, answer questions that students have raised about, and otherwise supplement the second edition of Basics of Biblical Hebrew by Pratico and Van Pelt. Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1.1 The consonants For begadkephat letters (§1.5), the pronunciation in §1.1 is the pronunciation with the Dagesh Lene (§1.5), even though the Dagesh Lene is not shown in §1.1. .Kaf” has an “off” sound“ כ The name It looks like open mouth coughing or a cup of coffee on its side. .Qof” is pronounced with either an “oh” sound or an “oo” sound“ ק The name It has a circle (like the letter “o” inside it). Also, it is transliterated with the letter q, and it looks like a backwards q. here are different wa s of spellin the na es of letters. lef leph leˉ There are many different ways to write the consonants. See below (page 3) for a table of examples. See my chapter 1 overheads for suggested letter shapes, stroke order, and the keys to distinguishing similar-looking letters. ”.having its dot on the left: “Sin is never ri ht ׂש Mnemonic for Sin ׁש and Shin ׂש Order of Sin ׁש before Shin ׂש Our textbook and Biblical Hebrew lexicons put Sin Some alphabet songs on YouTube reverse the order of Sin and Shin. Modern Hebrew dictionaries, the acrostic poems in the Bible, and ancient abecedaries (inscriptions in which someone wrote the alphabet) all treat Sin and Shin as the same letter. -

0. Introduction L2/12-386

Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Revised Proposal to Encode Additional Old Italic Characters Source: UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative (Universal Scripts Project) Author: Christopher C. Little ([email protected]) Status: Liaison Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N4046 (L2/11-146R) Date: 2012-11-06 0. Introduction The existing Old Italic character repertoire includes 31 letters and 4 numerals. The Unicode Standard, following the recommendations in the proposal L2/00-140, states that Old Italic is to be used for the encoding of Etruscan, Faliscan, Oscan, Umbrian, North Picene, and South Picene. It also specifically states that Old Italic characters are inappropriate for encoding the languages of ancient Italy north of Etruria (Venetic, Raetic, Lepontic, and Gallic). It is true that the inscriptions of languages north of Etruria exhibit a number of common features, but those features are often exhibited by the other scripts of Italy. Only one of these northern languages, Raetic, requires the addition of any additional characters in order to be fully supported by the Old Italic block. Accordingly, following the addition of this one character, the Unicode Standard should be amended to recommend the encoding of Venetic, Raetic, Lepontic, and Gallic using Old Italic characters. In addition, one additional character is necessary to encode South Picene inscriptions. This proposal is divided into five parts: The first part (§1) identifies the two unencoded characters (Raetic Ɯ and South Picene Ũ) and demonstrates their use in inscriptions. The second part (§2) examines the use of each Old Italic character, as it appears in Etruscan, Faliscan, Oscan, Umbrian, South Picene, Venetic, Raetic, Lepontic, Gallic, and archaic Latin, to demonstrate the unifiability of the northern Italic languages' scripts with Old Italic. -

PARK JIN HYOK, Also Known As ("Aka") "Jin Hyok Park," Aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case Fl·J 18 - 1 4 79

AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the RLED Central District of California CLERK U.S. DIS RICT United States ofAmerica JUN - 8 ?018 [ --- .. ~- ·~".... ~-~,..,. v. CENT\:y'\ l i\:,: ffl1G1 OF__ CAUFORN! BY .·-. ....-~- - ____D=E--..... PARK JIN HYOK, also known as ("aka") "Jin Hyok Park," aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case fl·J 18 - 1 4 79 Defendant. CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best ofmy knowledge and belief. Beginning no later than September 2, 2014 and continuing through at least August 3, 2017, in the county ofLos Angeles in the Central District of California, the defendant violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 371 Conspiracy 18 u.s.c. § 1349 Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud This criminal complaint is based on these facts: Please see attached affidavit. IBJ Continued on the attached sheet. Isl Complainant's signature Nathan P. Shields, Special Agent, FBI Printed name and title Sworn to before ~e and signed in my presence. Date: ROZELLA A OLIVER Judge's signature City and state: Los Angeles, California Hon. Rozella A. Oliver, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title -:"'~~ ,4G'L--- A-SA AUSAs: Stephanie S. Christensen, x3756; Anthony J. Lewis, x1786; & Anil J. Antony, x6579 REC: Detention Contents I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 II. PURPOSE OF AFFIDAVIT ......................................................................1 III. SUMMARY................................................................................................3 -

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — the LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D. Joseph, The Ohio State University 0. Introduction A stunning result of linguistic research in the 19th century was the recognition that some languages show correspondences of form that cannot be due to chance convergences, to borrowing among the languages involved, or to universal characteristics of human language, and that such correspondences therefore can only be the result of the languages in question having sprung from a common source language in the past. Such languages are said to be “related” (more specifically, “genetically related”, though “genetic” here does not have any connection to the term referring to a biological genetic relationship) and to belong to a “language family”. It can therefore be convenient to model such linguistic genetic relationships via a “family tree”, showing the genealogy of the languages claimed to be related. For example, in the model below, all the languages B through I in the tree are related as members of the same family; if they were not related, they would not all descend from the same original language A. In such a schema, A is the “proto-language”, the starting point for the family, and B, C, and D are “offspring” (often referred to as “daughter languages”); B, C, and D are thus “siblings” (often referred to as “sister languages”), and each represents a separate “branch” of the family tree. B and C, in turn, are starting points for other offspring languages, E, F, and G, and H and I, respectively. Thus B stands in the same relationship to E, F, and G as A does to B, C, and D. -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

Rock Art and Celto-Germanic Vocabulary Shared Iconography and Words As Reflections of Bronze Age Contact

John T. Koch Rock art and Celto-Germanic vocabulary Shared iconography and words as reflections of Bronze Age contact Abstract Recent discoveries in the chemical and isotopic sourcing of metals and ancient DNA have transformed our understanding of the Nordic Bronze Age in two key ways. First, we find that Scandinavia and the Iberian Peninsula were in contact within a system of long- distance exchange of Baltic amber and Iberian copper. Second, by the Early Bronze Age, mass migrations emanating from the Pontic-Caspian steppe had reached both regions, probably bringing Indo-European languages with them. In the light of these discoveries, we launched a research project in 2019 — ‘Rock art, Atlantic Europe, Words & Warriors (RAW)’ — based at the University of Gothenburg and funded by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet). The RAW project undertakes an extensive programme of scanning and documentation to enable detailed comparison of the strikingly similar iconography of Scandinavian rock art and Iberian ‘warrior’ stelae. A linguistic aspect of this cross-disciplinary project is to re-examine the inherited word stock shared by Celtic and Germanic, but absent from the other Indo-European languages, exploring how these words might throw light onto the world of meaning of Bronze rock art and the people who made it. This paper presents this linguistic aspect of the RAW project and some pre- liminary findings. Keywords: rock art, Bronze Age, Proto-Celtic, Proto-Germanic Introduction The recurrent themes and concepts found migrations emanating from the Pontic- in both the rock art of Scandinavia and Caspian steppe spreading widely across the Late Bronze Age ‘warrior’ stelae of the Western Eurasia, transforming the popula- Iberian Peninsula could undoubtedly also tions of regions including Southern Scan- be expressed in words. -

Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Václav Blažek (Masaryk University of Brno, Czech Republic) On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: Survey The purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo-European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non-Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian 0.3. Vladimir Georgiev (1981, 363) included in his Indo-European classification some of the relic languages, plus the languages with a doubtful IE affiliation at all: Tocharian Northern Balto-Slavic Germanic Celtic Ligurian Italic & Venetic Western Illyrian Messapic Siculian Greek & Macedonian Indo-European Central Phrygian Armenian Daco-Mysian & Albanian Eastern Indo-Iranian Thracian Southern = Aegean Pelasgian Palaic Southeast = Hittite; Lydian; Etruscan-Rhaetic; Elymian = Anatolian Luwian; Lycian; Carian; Eteocretan 0.4. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo-European and Germanic Background Indo-European Background It has already been mentioned in this course that German and English are related languages. Two languages can be related to each other in much the same way that two people can be related to each other. If two people share a common ancestor, say their mother or their great-grandfather, then they are genetically related. Similarly, German and English are genetically related because they share a common ancestor, a language which was spoken in what is now northern Germany sometime before the Angles and the Saxons migrated to England. We do not have written records of this language, unfortunately, but we have a good idea of what it must have looked and sounded like. We have arrived at our conclusions as to what it looked and sounded like by comparing the sounds of words and morphemes in earlier written stages of English and German (and Dutch) and in modern-day English and German dialects. As a result of the comparisons we are able to reconstruct what the original language, called a proto-language, must have been like. This particular proto-language is usually referred to as Proto-West Germanic. The method of reconstruction based on comparison is called the comparative method. If faced with two languages the comparative method can tell us one of three things: 1) the two languages are related in that both are descended from a common ancestor, e.g. German and English, 2) the two are related in that one is the ancestor of the other, e.g. -

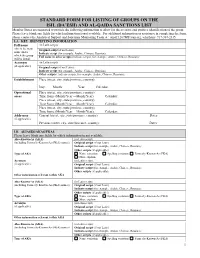

Standard Form for Listing of Groups on the Isil (Da'esh) and Al-Qaida

STANDARD FORM FOR LISTING OF GROUPS ON THE ISIL (DA’ESH) AND AL-QAIDA SANCTIONS LIST Member States are requested to provide the following information to allow for the accurate and positive identification of the group. Please leave blank any fields for which information is not available. For additional information or assistance in completing the form, please contact the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team at : email:[email protected], telephone: 917-367-2315. I.A. KEY IDENTIFYING INFORMATION Full name (in Latin script) (this is the main Original script (if not Latin): name under Indicate script (for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): which the group Full name in other scripts (indicate scripts, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): will be listed) Acronym (in Latin script) (if applicable) Original script (if not Latin): Indicate script (for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): Other scripts ( indicate scripts, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): Establishment Place (street, city, state/province, country): Day: Month: Year: Calendar: Operational Place (street, city, state/province, country): areas Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Place (street, city, state/province, country): Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Place (street, city, state/province, country): Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Addresses Current (street, city, state/province, country): Dates: (if applicable) Previous (street, city, state/province, country): Dates: I.B. ALIASES/AKAS/FKAS Please leave blank any fields for which -

Indo-European Languages and Branches

Indo-European languages and branches Language Relations One of the first hurdles anyone encounters in studying a foreign language is learning a new vocabulary. Faced with a list of words in a foreign language, we instinctively scan it to see how many of the words may be like those of our own language.We can provide a practical example by surveying a list of very common words in English and their equivalents in Dutch, Czech, and Spanish. A glance at the table suggests that some words are more similar to their English counterparts than others and that for an English speaker the easiest or at least most similar vocabulary will certainly be that of Dutch. The similarities here are so great that with the exception of the words for ‘dog’ (Dutch hond which compares easily with English ‘hound’) and ‘pig’ (where Dutch zwijn is the equivalent of English ‘swine’), there would be a nearly irresistible temptation for an English speaker to see Dutch as a bizarrely misspelled variety of English (a Dutch reader will no doubt choose to reverse the insult). When our myopic English speaker turns to the list of Czech words, he discovers to his pleasant surprise that he knows more Czech than he thought. The Czech words bratr, sestra,and syn are near hits of their English equivalents. Finally, he might be struck at how different the vocabulary of Spanish is (except for madre) although a few useful correspondences could be devised from the list, e.g. English pork and Spanish puerco. The exercise that we have just performed must have occurred millions of times in European history as people encountered their neighbours’ languages. -

The Ancient People of Italy Before the Rise of Rome, Italy Was a Patchwork

The Ancient People of Italy Before the rise of Rome, Italy was a patchwork of different cultures. Eventually they were all subsumed into Roman culture, but the cultural uniformity of Roman Italy erased what had once been a vast array of different peoples, cultures, languages, and civilizations. All these cultures existed before the Roman conquest of the Italian Peninsula, and unfortunately we know little about any of them before they caught the attention of Greek and Roman historians. Aside from a few inscriptions, most of what we know about the native people of Italy comes from Greek and Roman sources. Still, this information, combined with archaeological and linguistic information, gives us some idea about the peoples that once populated the Italian Peninsula. Italy was not isolated from the outside world, and neighboring people had much impact on its population. There were several foreign invasions of Italy during the period leading up to the Roman conquest that had important effects on the people of Italy. First there was the invasion of Alexander I of Epirus in 334 BC, which was followed by that of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 280 BC. Hannibal of Carthage invaded Italy during the Second Punic War (218–203 BC) with the express purpose of convincing Rome’s allies to abandon her. After the war, Rome rearranged its relations with many of the native people of Italy, much influenced by which peoples had remained loyal and which had supported their Carthaginian enemies. The sides different peoples took in these wars had major impacts on their destinies. In 91 BC, many of the peoples of Italy rebelled against Rome in the Social War.