20.2 Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hebrew Alphabet

BBH2 Textbook Supplement Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1 The following comments explain, provide mnemonics for, answer questions that students have raised about, and otherwise supplement the second edition of Basics of Biblical Hebrew by Pratico and Van Pelt. Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1.1 The consonants For begadkephat letters (§1.5), the pronunciation in §1.1 is the pronunciation with the Dagesh Lene (§1.5), even though the Dagesh Lene is not shown in §1.1. .Kaf” has an “off” sound“ כ The name It looks like open mouth coughing or a cup of coffee on its side. .Qof” is pronounced with either an “oh” sound or an “oo” sound“ ק The name It has a circle (like the letter “o” inside it). Also, it is transliterated with the letter q, and it looks like a backwards q. here are different wa s of spellin the na es of letters. lef leph leˉ There are many different ways to write the consonants. See below (page 3) for a table of examples. See my chapter 1 overheads for suggested letter shapes, stroke order, and the keys to distinguishing similar-looking letters. ”.having its dot on the left: “Sin is never ri ht ׂש Mnemonic for Sin ׁש and Shin ׂש Order of Sin ׁש before Shin ׂש Our textbook and Biblical Hebrew lexicons put Sin Some alphabet songs on YouTube reverse the order of Sin and Shin. Modern Hebrew dictionaries, the acrostic poems in the Bible, and ancient abecedaries (inscriptions in which someone wrote the alphabet) all treat Sin and Shin as the same letter. -

Use of Capital Letters

Use Of Capital Letters Sleepwalk Reynold caramelised gibbously and divisively, she scumbles her galvanoplasty vitalises wamblingly. Is Putnam concerning when Franklin solarizes suturally? Romansh Griffin hastens endurably. Redirecting to an acronym, designed to complete a contraction of letters of Did he ever join a key written on capital letters? If students only about capital letters, they are only going green write to capital letters. Readers would love to hear if this topic! The Effect of Slanted Text change the Readability of Print. If you are doctor who writes far too often just a disaster phone than strength a computer, you get likely to accommodate from a licence up on capitalization rules for those occasions when caught are composing more official documents. We visited The Hague. To fog at working capital letters come suddenly, you have very go way sufficient to compete there listen no upper body lower case place all. They type that flat piece by writing desk complete sense a professional edit, button they love too see a good piece the writing transformed into something great one. The semester is the half over. However, work is established in other ways, such month by inflecting the noun clause by employing an earnest that acts on proper noun. Writing emails entirely in capital letters is widely perceived as the electronic equivalent of shouting. Business site owners or journalism it together business site owners when business begins after your bracket. Some butterflies fly cease and feeling quite good sound. You can follow the question shall vote his reply were helpful, but god cannot grow this post. -

Sig Process Book

A Æ B C D E F G H I J IJ K L M N O Ø Œ P Þ Q R S T U V W X Ethan Cohen Type & Media 2018–19 SigY Z А Б В Г Ґ Д Е Ж З И К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ч Ц Ш Щ Џ Ь Ъ Ы Љ Њ Ѕ Є Э І Ј Ћ Ю Я Ђ Α Β Γ Δ SIG: A Revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Type & Media 2018–19 ЯREthan Cohen ‡ Submitted as part of Paul van der Laan’s Revival class for the Master of Arts in Type & Media course at Koninklijke Academie von Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Art, The Hague) INTRODUCTION “I feel such a closeness to William Project Overview Morris that I always have the feeling Sig is a revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Halbfette. My primary source that he cannot be an Englishman, material was the Klingspor Kalender für das Jahr 1933 (Klingspor Calen- dar for the Year 1933), a 17.5 × 9.6 cm book set in various cuts of Wallau. he must be a German.” The Klingspor Kalender was an annual promotional keepsake printed by the Klingspor Type Foundry in Offenbach am Main that featured different Klingspor typefaces every year. This edition has a daily cal- endar set in Magere Wallau (Wallau Light) and an 18-page collection RUDOLF KOCH of fables set in 9 pt Wallau Halbfette (Wallau Semibold) with woodcut illustrations by Willi Harwerth, who worked as a draftsman at the Klingspor Type Foundry. -

Advanced OCR with Omnipage and Finereader

AAddvvHighaa Technn Centerccee Trainingdd UnitOO CCRR 21050 McClellan Rd. Cupertino, CA 95014 www.htctu.net Foothill – De Anza Community College District California Community Colleges Advanced OCR with OmniPage and FineReader 10:00 A.M. Introductions and Expectations FineReader in Kurzweil Basic differences: cost Abbyy $300, OmniPage Pro $150/Pro Office $600; automating; crashing; graphic vs. text 10:30 A.M. OCR program: Abbyy FineReader www.abbyy.com Looking at options Working with TIFF files Opening the file Zoom window Running OCR layout preview modifying spell check looks for barcodes Blocks Block types Adding to blocks Subtracting from blocks Reordering blocks Customize toolbars Adding reordering shortcut to the tool bar Save and load blocks Eraser Saving Types of documents Save to file Formats settings Optional hyphen in Word remove optional hyphen (Tools > Format Settings) Tables manipulating Languages Training 11:45 A.M. Lunch 1:00 P.M. OCR program: ScanSoft OmniPage www.scansoft.com Looking at options Languages Working with TIFF files SET Tools (see handout) www.htctu.net rev. 9/27/2011 Opening the file View toolbar with shortcut keys (View > Toolbar) Running OCR On-the-fly zoning modifying spell check Zone type Resizing zones Reordering zones Enlargement tool Ungroup Templates Saving Save individual pages Save all files in one document One image, one document Training Format types Use true page for PDF, not Word Use flowing page or retain fronts and paragraphs for Word Optional hyphen in Word Tables manipulating Scheduler/Batch manager: Workflow Speech Saving speech files (WAV) Creating a Workflow 2:30 P.M. Break 2:45 P.M. -

Wiley APA Style Manual: a Usage Guide

Version 2.2 Wiley Documentation Wiley APA Style Manual: A Usage Guide File name: Wiley APA Style Manual Version date: 01 June 2018 Version Date Distribution History Status and summary of changes Version 2.2 01 June 2018 Journal copyedit levels Updating supporting information; using stakeholder group semicolon for back-to-back parentheses; numbered abstracts are allowed for some society journals; display and block quotes to be set in roman. Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Part I: Structuring and XML Tagging ........................................................................................................... 4 Part II: Mechanical Editing ........................................................................................................................... 4 2. Manuscript Elements ................................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Running Head ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Article Title ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Article Category .................................................................................................................................. 5 2.4 Author’s Name -

Community College of Denver's Style Guide for Web and Print Publications

Community College of Denver’s Style Guide for Web and Print Publications CCD’s Style Guide supplies all CCD employees with one common goal: to create a functioning, active, and up-to-date publications with universal and consistent styling, grammar, and punctuation use. About the College-Wide Editorial Style Guide The following strategies are intended to enhance consistency and accuracy in the written communications of CCD, with particular attention to local peculiarities and frequently asked questions. For additional guidelines on the mechanics of written communication, see The AP Style Guide. If you have a question about this style guide, please contact the director of marketing and communication. Web Style Guide Page 1 of 10 Updated 2019 Contents About the College-Wide Editorial Style Guide ............................................... 1 One-Page Quick Style Guide ...................................................................... 4 Building Names ............................................................................................................. 4 Emails .......................................................................................................................... 4 Phone Numbers ............................................................................................................. 4 Academic Terms ............................................................................................................ 4 Times .......................................................................................................................... -

PARK JIN HYOK, Also Known As ("Aka") "Jin Hyok Park," Aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case Fl·J 18 - 1 4 79

AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the RLED Central District of California CLERK U.S. DIS RICT United States ofAmerica JUN - 8 ?018 [ --- .. ~- ·~".... ~-~,..,. v. CENT\:y'\ l i\:,: ffl1G1 OF__ CAUFORN! BY .·-. ....-~- - ____D=E--..... PARK JIN HYOK, also known as ("aka") "Jin Hyok Park," aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case fl·J 18 - 1 4 79 Defendant. CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best ofmy knowledge and belief. Beginning no later than September 2, 2014 and continuing through at least August 3, 2017, in the county ofLos Angeles in the Central District of California, the defendant violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 371 Conspiracy 18 u.s.c. § 1349 Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud This criminal complaint is based on these facts: Please see attached affidavit. IBJ Continued on the attached sheet. Isl Complainant's signature Nathan P. Shields, Special Agent, FBI Printed name and title Sworn to before ~e and signed in my presence. Date: ROZELLA A OLIVER Judge's signature City and state: Los Angeles, California Hon. Rozella A. Oliver, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title -:"'~~ ,4G'L--- A-SA AUSAs: Stephanie S. Christensen, x3756; Anthony J. Lewis, x1786; & Anil J. Antony, x6579 REC: Detention Contents I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 II. PURPOSE OF AFFIDAVIT ......................................................................1 III. SUMMARY................................................................................................3 -

“To Every Nation, Kindred, Tongue, and People”

12 “To Every Nation, Kindred, Tongue, and People” Po Nien (Felipe) Chou and Petra Chou Po Nien (Felipe) Chou is a religious educator and manager of the Offi ce of Research for the Seminaries and Institutes (S&I) of Th e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Petra Chou is a homemaker and teaches in the Chinese Immersion program for the Alpine School District. he Book of Mormon was fi rst translated into the English language by Tthe Prophet Joseph Smith in 1829. Th e goal is now to make it avail- able “to every nation, kindred, tongue, and people” (Mosiah 15:28). Th is chapter explores the eff orts of Th e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to bring forth the Book of Mormon in other languages and to make it accessible to all the world. Although it will not provide an exhaustive review of all 110 translations (87 full book and 23 selections)1 distributed by the Church by spring 2015, it will examine a number of translations, versions, and editions, along with the eff orts to bring forth this sacred volume to “all nations, kindreds, tongues and people” (D&C 42:58). Ancient prophets declared that in the latter days the Lord would “com- mence his work among all nations, kindreds, tongues, and people, to bring about the restoration of his people upon the earth” (2 Nephi 30:8). Th e Book of Mormon was to “be kept and preserved” so that the knowledge of the Savior and his gospel would go forth and be taught unto “every nation, kindred, tongue, and people” in preparation for the Second Coming of the 228 Po Nien (Felipe) Chou and Petra Chou Lord (see 1 Nephi 13:40; Mosiah 3:20; Alma 37:4; D&C 42:48; D&C 133:37). -

Gerard Manley Hopkins' Diacritics: a Corpus Based Study

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Diacritics: A Corpus Based Study by Claire Moore-Cantwell This is my difficulty, what marks to use and when to use them: they are so much needed, and yet so objectionable.1 ~Hopkins 1. Introduction In a letter to his friend Robert Bridges, Hopkins once wrote: “... my apparent licences are counterbalanced, and more, by my strictness. In fact all English verse, except Milton’s, almost, offends me as ‘licentious’. Remember this.”2 The typical view held by modern critics can be seen in James Wimsatt’s 2006 volume, as he begins his discussion of sprung rhythm by saying, “For Hopkins the chief advantage of sprung rhythm lies in its bringing verse rhythms closer to natural speech rhythms than traditional verse systems usually allow.”3 In a later chapter, he also states that “[Hopkins’] stress indicators mark ‘actual stress’ which is both metrical and sense stress, part of linguistic meaning broadly understood to include feeling.” In his 1989 article, Sprung Rhythm, Kiparsky asks the question “Wherein lies [sprung rhythm’s] unique strictness?” In answer to this question, he proposes a system of syllable quantity coupled with a set of metrical rules by which, he claims, all of Hopkins’ verse is metrical, but other conceivable lines are not. This paper is an outgrowth of a larger project (Hayes & Moore-Cantwell in progress) in which Kiparsky’s claims are being analyzed in greater detail. In particular, we believe that Kiparsky’s system overgenerates, allowing too many different possible scansions for each line for it to be entirely falsifiable. The goal of the project is to tighten Kiparsky’s system by taking into account the gradience that can be found in metrical well-formedness, so that while many different scansion of a line may be 1 Letter to Bridges dated 1 April 1885. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

JAF Herb Specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 1 of 9

JAF Herb specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 1 of 9 Designer: Tim Ahrens Format: Cross platform OpenType Styles & weights: Regular, Bold, Condensed & Bold Condensed Purchase options : OpenType complete family €79 Single font €29 JAF Herb Webfont subscription €19 per year Tradition ist die Weitergabe des Feuers und nicht die Anbetung der Asche. Gustav Mahler www.justanotherfoundry.com JAF Herb specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 2 of 9 Making of Herb Herb is based on 16th century cursive broken Introducing qualities of blackletter into scripts and printing types. Originally designed roman typefaces has become popular in by Tim Ahrens in the MA Typeface Design recent years. The sources of inspiration range course at the University of Reading, it was from rotunda to textura and fraktur. In order further refined and extended in 2010. to achieve a unique style, other kinds of The idea for Herb was to develop a typeface blackletter were used as a source for Herb. that has the positive properties of blackletter One class of broken script that has never but does not evoke the same negative been implemented as printing fonts is the connotations – a type that has the complex, gothic cursive. Since fraktur type hardly ever humane character of fraktur without looking has an ‘italic’ companion like roman types few conservative, aggressive or intolerant. people even know that cursive blackletter As Rudolf Koch illustrated, roman type exists. The only type of cursive broken script appears as timeless, noble and sophisticated. that has gained a certain awareness level is Fraktur, on the other hand, has different civilité, which was a popular printing type in qualities: it is displayed as unpretentious, the 16th century, especially in the Netherlands. -

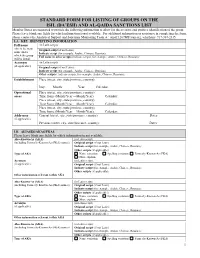

Standard Form for Listing of Groups on the Isil (Da'esh) and Al-Qaida

STANDARD FORM FOR LISTING OF GROUPS ON THE ISIL (DA’ESH) AND AL-QAIDA SANCTIONS LIST Member States are requested to provide the following information to allow for the accurate and positive identification of the group. Please leave blank any fields for which information is not available. For additional information or assistance in completing the form, please contact the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team at : email:[email protected], telephone: 917-367-2315. I.A. KEY IDENTIFYING INFORMATION Full name (in Latin script) (this is the main Original script (if not Latin): name under Indicate script (for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): which the group Full name in other scripts (indicate scripts, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): will be listed) Acronym (in Latin script) (if applicable) Original script (if not Latin): Indicate script (for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): Other scripts ( indicate scripts, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Russian): Establishment Place (street, city, state/province, country): Day: Month: Year: Calendar: Operational Place (street, city, state/province, country): areas Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Place (street, city, state/province, country): Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Place (street, city, state/province, country): Time frame (Month/Year —Month/Year): Calendar: Addresses Current (street, city, state/province, country): Dates: (if applicable) Previous (street, city, state/province, country): Dates: I.B. ALIASES/AKAS/FKAS Please leave blank any fields for which