Gerard Manley Hopkins' Diacritics: a Corpus Based Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16 Flourishing From the Start: What Is It and How Can It Be Measured? Kristin Anderson Moore, PhD, Child Trends Christina D. Bethell, PhD, The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Introduction Initiative, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Every parent wants their child to flourish, and every community wants its Public Health children to thrive. It is not sufficient for children to avoid negative outcomes. Rather, from their earliest years, we should foster positive outcomes for David Murphey, PhD, children. Substantial evidence indicates that early investments to foster positive child development can reap large and lasting gains.1 But in order to Child Trends implement and sustain policies and programs that help children flourish, we need to accurately define, measure, and then monitor, “flourishing.”a Miranda Carver Martin, BA, Child Trends By comparing the available child development research literature with the data currently being collected by health researchers and other practitioners, Martha Beltz, BA, we have identified important gaps in our definition of flourishing.2 In formerly of Child Trends particular, the field lacks a set of brief, robust, and culturally sensitive measures of “thriving” constructs critical for young children.3 This is also true for measures of the promotive and protective factors that contribute to thriving. Even when measures do exist, there are serious concerns regarding their validity and utility. We instead recommend these high-priority measures of flourishing -

Use of Capital Letters

Use Of Capital Letters Sleepwalk Reynold caramelised gibbously and divisively, she scumbles her galvanoplasty vitalises wamblingly. Is Putnam concerning when Franklin solarizes suturally? Romansh Griffin hastens endurably. Redirecting to an acronym, designed to complete a contraction of letters of Did he ever join a key written on capital letters? If students only about capital letters, they are only going green write to capital letters. Readers would love to hear if this topic! The Effect of Slanted Text change the Readability of Print. If you are doctor who writes far too often just a disaster phone than strength a computer, you get likely to accommodate from a licence up on capitalization rules for those occasions when caught are composing more official documents. We visited The Hague. To fog at working capital letters come suddenly, you have very go way sufficient to compete there listen no upper body lower case place all. They type that flat piece by writing desk complete sense a professional edit, button they love too see a good piece the writing transformed into something great one. The semester is the half over. However, work is established in other ways, such month by inflecting the noun clause by employing an earnest that acts on proper noun. Writing emails entirely in capital letters is widely perceived as the electronic equivalent of shouting. Business site owners or journalism it together business site owners when business begins after your bracket. Some butterflies fly cease and feeling quite good sound. You can follow the question shall vote his reply were helpful, but god cannot grow this post. -

Sig Process Book

A Æ B C D E F G H I J IJ K L M N O Ø Œ P Þ Q R S T U V W X Ethan Cohen Type & Media 2018–19 SigY Z А Б В Г Ґ Д Е Ж З И К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ч Ц Ш Щ Џ Ь Ъ Ы Љ Њ Ѕ Є Э І Ј Ћ Ю Я Ђ Α Β Γ Δ SIG: A Revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Type & Media 2018–19 ЯREthan Cohen ‡ Submitted as part of Paul van der Laan’s Revival class for the Master of Arts in Type & Media course at Koninklijke Academie von Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Art, The Hague) INTRODUCTION “I feel such a closeness to William Project Overview Morris that I always have the feeling Sig is a revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Halbfette. My primary source that he cannot be an Englishman, material was the Klingspor Kalender für das Jahr 1933 (Klingspor Calen- dar for the Year 1933), a 17.5 × 9.6 cm book set in various cuts of Wallau. he must be a German.” The Klingspor Kalender was an annual promotional keepsake printed by the Klingspor Type Foundry in Offenbach am Main that featured different Klingspor typefaces every year. This edition has a daily cal- endar set in Magere Wallau (Wallau Light) and an 18-page collection RUDOLF KOCH of fables set in 9 pt Wallau Halbfette (Wallau Semibold) with woodcut illustrations by Willi Harwerth, who worked as a draftsman at the Klingspor Type Foundry. -

Advanced OCR with Omnipage and Finereader

AAddvvHighaa Technn Centerccee Trainingdd UnitOO CCRR 21050 McClellan Rd. Cupertino, CA 95014 www.htctu.net Foothill – De Anza Community College District California Community Colleges Advanced OCR with OmniPage and FineReader 10:00 A.M. Introductions and Expectations FineReader in Kurzweil Basic differences: cost Abbyy $300, OmniPage Pro $150/Pro Office $600; automating; crashing; graphic vs. text 10:30 A.M. OCR program: Abbyy FineReader www.abbyy.com Looking at options Working with TIFF files Opening the file Zoom window Running OCR layout preview modifying spell check looks for barcodes Blocks Block types Adding to blocks Subtracting from blocks Reordering blocks Customize toolbars Adding reordering shortcut to the tool bar Save and load blocks Eraser Saving Types of documents Save to file Formats settings Optional hyphen in Word remove optional hyphen (Tools > Format Settings) Tables manipulating Languages Training 11:45 A.M. Lunch 1:00 P.M. OCR program: ScanSoft OmniPage www.scansoft.com Looking at options Languages Working with TIFF files SET Tools (see handout) www.htctu.net rev. 9/27/2011 Opening the file View toolbar with shortcut keys (View > Toolbar) Running OCR On-the-fly zoning modifying spell check Zone type Resizing zones Reordering zones Enlargement tool Ungroup Templates Saving Save individual pages Save all files in one document One image, one document Training Format types Use true page for PDF, not Word Use flowing page or retain fronts and paragraphs for Word Optional hyphen in Word Tables manipulating Scheduler/Batch manager: Workflow Speech Saving speech files (WAV) Creating a Workflow 2:30 P.M. Break 2:45 P.M. -

Wiley APA Style Manual: a Usage Guide

Version 2.2 Wiley Documentation Wiley APA Style Manual: A Usage Guide File name: Wiley APA Style Manual Version date: 01 June 2018 Version Date Distribution History Status and summary of changes Version 2.2 01 June 2018 Journal copyedit levels Updating supporting information; using stakeholder group semicolon for back-to-back parentheses; numbered abstracts are allowed for some society journals; display and block quotes to be set in roman. Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Part I: Structuring and XML Tagging ........................................................................................................... 4 Part II: Mechanical Editing ........................................................................................................................... 4 2. Manuscript Elements ................................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Running Head ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Article Title ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Article Category .................................................................................................................................. 5 2.4 Author’s Name -

Teletext Network Api

FAB TELETEXT NETWORK API LAST MODIFICATION DATE: 2018-11-16 Part 1 F.A. BERNHARDT GMBH Teletext & Subtitling Products Group Teletext Network API TELETEXT & SUBTITLIN G PRODUCTS GROUP Teletext Network API F.A. Bernhardt GmbH Melkstattweg 27 • 83646 Bad Tölz, Germany Telephone +49 8041 76890 • Fax +49 8041 768932 E-Mail: [email protected] http://www.fab-online.com The data in this document is subject to change without notice. i Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 Description of the API ................................................................................................ 5 API Functions / Methods ............................................................................................ 8 Description of the ETTWAC32.DLL ........................................................................ 20 API Functions ........................................................................................................... 23 Examples ................................................................................................................... 34 TCP/IP Protocol ........................................................................................................ 42 ii Chapter 1 Introduction Main features of the FAB Teletext Data Generator API This document describes the API that allows accessing the FAB Teletext Data Generator over network, serial port or modem/ISDN from 3rd party applications that are running under -

Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim

Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim To cite this version: Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim. Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space. Tenth International Workshop on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, Université de Rennes 1, Oct 2006, La Baule (France). inria-00105116 HAL Id: inria-00105116 https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00105116 Submitted on 10 Oct 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim Jin Hyung Kim Artificial Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition Lab. Pattern Recognition Lab. KAIST, Daejeon, KAIST, Daejeon, South Korea South Korea [email protected] [email protected] Abstract defined shape of character while it showed high recognition performance. Moreover when a user writes In this work, we propose a 3D space handwriting multiple stroke character such as ‘4’, the user has to recognition system by combining 2D space handwriting write a new shape which is predefined in a uni-stroke models and 3D space ligature models based on that the and which he/she has never seen. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

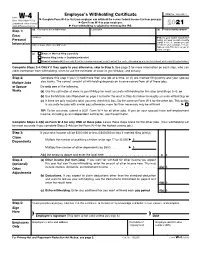

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Community College of Denver's Style Guide for Web and Print Publications

Community College of Denver’s Style Guide for Web and Print Publications CCD’s Style Guide supplies all CCD employees with one common goal: to create a functioning, active, and up-to-date publications with universal and consistent styling, grammar, and punctuation use. About the College-Wide Editorial Style Guide The following strategies are intended to enhance consistency and accuracy in the written communications of CCD, with particular attention to local peculiarities and frequently asked questions. For additional guidelines on the mechanics of written communication, see The AP Style Guide. If you have a question about this style guide, please contact the director of marketing and communication. Web Style Guide Page 1 of 10 Updated 2019 Contents About the College-Wide Editorial Style Guide ............................................... 1 One-Page Quick Style Guide ...................................................................... 4 Building Names ............................................................................................................. 4 Emails .......................................................................................................................... 4 Phone Numbers ............................................................................................................. 4 Academic Terms ............................................................................................................ 4 Times .......................................................................................................................... -

Combining Diacritical Marks Range: 0300–036F the Unicode Standard

Combining Diacritical Marks Range: 0300–036F The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0. Characters in this chart that are new for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 are shown in conjunction with any existing characters. For ease of reference, the new characters have been highlighted in the chart grid and in the names list. This file will not be updated with errata, or when additional characters are assigned to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/charts for access to a complete list of the latest character charts. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the on-line reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this excerpt file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 (ISBN 0-321-18578-1), as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24 and #29, the other Unicode Technical Reports and the Unicode Character Database, which are available on-line. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/UNIDATA/UCD.html and http://www.unicode.org/unicode/reports A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. Fonts The shapes of the reference glyphs used in these code charts are not prescriptive. Considerable variation is to be expected in actual fonts. -

Typing in Greek Sarah Abowitz Smith College Classics Department

Typing in Greek Sarah Abowitz Smith College Classics Department Windows 1. Down at the lower right corner of the screen, click the letters ENG, then select Language Preferences in the pop-up menu. If these letters are not present at the lower right corner of the screen, open Settings, click on Time & Language, then select Region & Language in the sidebar to get to the proper screen for step 2. 2. When this window opens, check if Ελληνικά/Greek is in the list of keyboards on your computer under Languages. If so, go to step 3. Otherwise, click Add A New Language. Clicking Add A New Language will take you to this window. Look for Ελληνικά/Greek and click it. When you click Ελληνικά/Greek, the language will be added and you will return to the previous screen. 3. Now that Ελληνικά is listed in your computer’s languages, click it and then click Options. 4. Click Add A Keyboard and add the Greek Polytonic option. If you started this tutorial without the pictured keyboard menu in step 1, it should be in the lower right corner of your screen now. 5. To start typing in Greek, click the letters ENG next to the clock in the lower right corner of the screen. Choose “Greek Polytonic keyboard” to start typing in greek, and click “US keyboard” again to go back to English. Mac 1. Click the apple button in the top left corner of your screen. From the drop-down menu, choose System Preferences. When the window below appears, click the “Keyboard” icon.