Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

7.5 Heian Notes

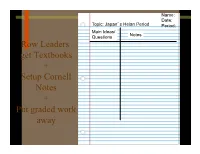

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

Bonsai Pdf 5/31/06 11:18 AM Page 1

Bonsai pdf 5/31/06 11:18 AM Page 1 THE BONSAI COLLECTION The Chicago Botanic Garden’s bonsai collection is regarded by bonsai experts as one of the best public collections in the world. It includes 185 bonsai in twenty styles and more than 40 kinds of plants, including evergreen, deciduous, tropical, flowering and fruiting trees. Since the entire collection cannot be displayed at once, select species are rotated through a display area in the Education Center’s East Courtyard from May through October. Each one takes the stage when it is most beautiful. To see photographs of bonsai from the collection, visit www.chicagobotanic.org/bonsai. Assembling the Collection Predominantly composed of donated specimens, the collection includes gifts from BONSAI local enthusiasts and Midwest Bonsai Society members. In 2000, Susumu Nakamura, a COLLECTION Japanese bonsai master and longstanding friend of the Chicago Botanic Garden, donated 19 of his finest bonsai to the collection. This A remarkable collection gift enabled the collection to advance to of majestic trees world-class status. in miniature Caring for the Collection When not on display, the bonsai in the Chicago Botanic Garden’s collection are housed in a secured greenhouse that has both outdoor and indoor facilities. There the bonsai are watered, fertilized, wired, trimmed and repotted by staff and volunteers. Several times a year, bonsai master Susumu Nakamura travels from his home in Japan to provide guidance for the care and training of this important collection. What Is a Bonsai? Japanese and Chinese languages use the same characters to represent bonsai (pronounced “bone-sigh”). -

Advanced Master Gardener Landscape Gardening For

ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER LANDSCAPE GARDENING FOR GARDENERS 2002 The Quest Continues 11 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 LARRY A. SAGERS PROFFESOR UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY 21 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 GRETCHEN CAMPBELL • MASTER GARDENER COORDINATOR AT THANKSGIVING POINT INSTITUE 31 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 41 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Life according to the Bible began in a garden. • Wherever that garden was located that was planted eastward in Eden, there were many plants that Adam and Eve were to tend. • The Garden provided”every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food” 51 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Other cultures have similar stories. • Stories come from Native Americans African tribes, Polynesians and Aborigines and many other groups of gardens as a place of life 61 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Teachings and legends influence art, religion, education and gardens. • The how and why of the different geographical and cultural influences on Landscape Gardening is the theme of the 2002 Advanced Master Gardening course at Thanksgiving Point Institute. 71 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Earliest known indications of Agriculture only go back about 10,000 years • Bouquets of flowers have been found in tombs some 60,000 years old • These may have had aesthetic or ritual roles 81 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Evidence of gardens in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates -

Samurai Life in Medieval Japan

http://www.colorado.edu/ptea-curriculum/imaging-japanese-history Handout M2 (Print Version) Page 1 of 8 Samurai Life in Medieval Japan The Heian period (794-1185) was followed by 700 years of warrior governments—the Kamakura, Muromachi, and Tokugawa. The civil government at the imperial court continued, but the real rulers of the country were the military daimy class. You will be using art as a primary source to learn about samurai and daimy life in medieval Japan (1185-1603). Kamakura Period (1185-1333) The Kamakura period was the beginning of warrior class rule. The imperial court still handled civil affairs, but with the defeat of the Taira family, the Minamoto under Yoritomo established its capital in the small eastern city of Kamakura. Yoritomo received the title shogun or “barbarian-quelling generalissimo.” Different clans competed with one another as in the Hgen Disturbance of 1156 and the Heiji Disturbance of 1159. The Heiji Monogatari Emaki is a hand scroll showing the armor and battle strategies of the early medieval period. The conflict at the Sanj Palace was between Fujiwara Nobuyori and Minamoto Yoshitomo. As you look at the scroll, notice what people are wearing, the different roles of samurai and foot soldiers, and the different weapons. What can you learn about what is involved in this disturbance? What can you learn about the samurai and the early medieval period from viewing this scroll? What information is helpful in developing an accurate view of samurai? What preparations would be necessary to fight these kinds of battles? (Think about the organization of people, equipment, and weapons; the use of bows, arrows, and horses; use of protective armor for some but not all; and the different ways of fighting.) During the Genpei Civil War of 1180-1185, Yoritomo fought against and defeated the Taira, beginning the Kamakura Period. -

Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

1 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian Sophia University Tokyo, Japan 2 Contents About this Book ......................................................................................... 4 The Editor ................................................................................................ 5 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know ................................................. 6 Contributors of This Book ............................................................................ 94 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 96 Further Reading on Japanese Management .................................................... 102 3 About this Book This book is the result of one of my “Management in Japan” classes held at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Sophia University in Tokyo. Students wrote this dictionary entries, I edited and updated them. The document is now available as a free e-book at my homepage www.haghirian.com. We hope that this book improves understanding of Japanese management and serves as inspiration for anyone interested in the subject. Questions and comments can be sent to [email protected]. Please inform the editor if you plan to quote parts of the book. Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian First edition, Tokyo, October 2019 4 The Editor Parissa Haghirian is Professor of International Management at Sophia University in Tokyo. She lives and works in Japan since 2004 -

Print This Article

148 | Japanese Language and Literature Reynolds in fact explicates Abe Kōbō’s The Box Man, in terms of its urban space/visuality nexus, which is a subject of Prichard’s chapter 4. Thus, more extensive engagement with Reynolds’s work would be desirable. On a more technical note, Japanese titles/terms are often not represented, even when there is no existing translation or established English equivalent; instead, only their approximate English translation is provided in the main body, the notes, or the index. Readers would benefit from being able to look further into such sources with the citation of original titles and terms, at least in their first appearance in the volume. It would also be highly desirable to correlate reprinted images with applicable passages in which they are closely and insightfully explicated (as, for example, on pages 168 and 186), so that readers could collate the two mediums point by point, verifying the author’s argument. There should also be a list of illustrations and a list of copyright owners (only the cover photo is credited in full, on the back cover). Residual Futures addresses timely critical issues that many of us share and has succeeded in creating a network of considerations across premeditated disciplines. With its examinations of documentary film, which is by default multimedia, and of visually oriented authors such as Abe and textually prolific artists such as Nakahira, this book will command attention from a wide range of scholars and other critically minded readers to urgent consideration of these registers, as well as of the urban space they formed and transformed. -

A Re-Examination of Restoration Shinto”

PROVISIONAL TRANSLATION (December 2018) Only significant errors of English in the translation have been corrected––the content will be checked against the original Japanese for accuracy at a later date. Supplemental Chapter: “A Re-examination of Restoration Shinto” MATSU’URA MITSUNOBU HE first of the three chapters in this monograph examined the relationship between Takamasa and Atsutane; the second one discussed Takamasa’s view on kokugaku shitaijin T (the four highly esteemed scholars in the Edo period who specialized in Japanese nativistic learning); and the third one considered Takamasa’s thoughts on the Shinto religion. Through a thorough examination in the three chapters, it questioned Takamasa’s thoughts on the four scholars of nativistic learning, and argued that, although his views on them are acknowledged as one of several interpretations on the history of nativistic learning, it was only one “narrative.” Was his narrative objectively correct? If not, what would a new narrative look like? This essay covers the author’s response to these questions. Hirata Atsutane considered Kada no Azumamaro to be the founder of nativistic learning, even though he had little knowledge of him at the time. According to research on nativistic learning that was conducted before World War II, Azumamaro’s theory on Shinto was clearly understood as Confucianism. His theory on Shinto is similar to so-called Juka Shinto (Confucian Shinto). Although Kamo no Mabuchi was Azumamaro’s disciple, he was critical of Azumamaro’s theory. Furthermore, Mabuchi did not build his theory upon Azumamaro’s. It was Keichū who influenced Mabuchi academically, and it is widely known that Keichū’s “theory on Japanese classical literature” opened Norinaga’s eyes to Shinto. -

Upcoming Events 2021 Virtual BSOP Meeting: February 23, 6:00Pm, Special Joint BSOP/Mirai Program Featuring Ryan Neil on Repotting

February Upcoming Events 2021 Virtual BSOP Meeting: February 23, 6:00pm, Special joint BSOP/Mirai program featuring Ryan Neil on repotting. February 24, 6:30—8:00pm, BSOP Repotting Q&A with Ryan Neil March 13 10:00 - 11:30am, Mentorship Presents; Repotting March 23, 7-9pm, Monthly Meeting- Jonas Dupuich on long term pine development National Meeting: September 11-12, 2021, US National Bonsai Exhibition. Rochester, NY 14445 2021 Words From the President Greetings BSOP, I hope everyone is enjoying the snow and winter weather that this month has brought us - I personally love seeing snow fall in the bonsai garden. While the pandemic has halted our in-person gatherings, I hope you have and plan to take advantage of our digital program- ming. We're offering two Zoom presentations each month until the pandemic passes, with no summer break. This month I'll be giving a program on deciduous nebari techniques, and later Ryan Neil will be giving a BSOP sponsored public stream on February 23rd, and will be giving a private BSOP members-only Repotting Q&A session on February 24th. We have some of the biggest names in bonsai presenting to our club this year on Zoom, so please tune in and catch a program. In spite of this winter weather, it's time to start thinking about repotting season, if you haven't already! Make sure you protect repotted bonsai from freezing temperatures and wind. Bonsai undergoing a drastic repot might even appreciate a heat pad. For aftercare, typically 3-4 weeks in the greenhouse after repotting is a good guideline, but keep an eye on the weather. -

Heian Literature in Manga"

H-Japan Publication "Heian Literature in Manga" Discussion published by Gergana Ivanova on Friday, April 23, 2021 Dear Colleagues, I am writing to announce the publication of a collection of articles inJapanese Language and Literature (JLL) that focus on manga adaptations of Heian-period literary works. Titled “Heian Literature in Manga,” this special section of the journal explores the multiple functions that manga rewritings of classical literature perform in present-day Japan. The articles examine recent rewritings of the following works:Taketori monogatari, Ise monogatari, Makura no sōshi, Genji monogatari, Sarashina nikki, and Izumi Shikibu nikki. Some of the questions these studies address are: Why do so many manga adaptations of Japanese “classics” appear in the book market every year? Why are they marketed as educational tools although they differ tremendously from the source texts? What influence has manga had in popularizing classical literature? How are literary works of the distant past utilized to address current social issues in Japan, including women’s empowerment, sexual violence, gender and sexuality, and cultural nationalism? “All of these articles demonstrate how manga adaptations recontextualize Heian writers and their works in the familiar landscape of today to bring them closer to the reader and emphasize the timeless and enduring character of classical literature. Using contemporary Japanese slang, visually stunning art, and universal themes such as sexuality, family, and life paths for women, manga successfully transform ancient texts into engaging, accessible works that continue to spark interest in Japan’s literary heritage in the twenty-first century and broaden readers’ knowledge of the past. These studies can thus contribute to effective teaching of classical literature both within and outside Japan.” The articles can be accessed here: https://jll.pitt.edu/ojs/JLL . -

Kamakura Period, Early 14Th Century Japanese Cypress (Hinoki) with Pigment, Gold Powder, and Cut Gold Leaf (Kirikane) H

A TEACHER RESOURCE 1 2 Project Director Nancy C. Blume Editor Leise Hook Copyright 2016 Asia Society This publication may not be reproduced in full without written permission of Asia Society. Short sections—less than one page in total length— may be quoted or cited if Asia Society is given credit. For further information, write to Nancy Blume, Asia Society, 725 Park Ave., New York, NY 10021 Cover image Nyoirin Kannon Kamakura period, early 14th century Japanese cypress (hinoki) with pigment, gold powder, and cut gold leaf (kirikane) H. 19½ x W. 15 x D. 12 in. (49.5 x 38.1 x 30.5 cm) Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.205 Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society 3 4 Kamakura Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan Art is of intrinsic importance to the educational process. The arts teach young people how to learn by inspiring in them the desire to learn. The arts use a symbolic language to convey the cultural values and ideologies of the time and place of their making. By including Asian arts in their curriculums, teachers can embark on culturally diverse studies and students will gain a broader and deeper understanding of the world in which they live. Often, this means that students will be encouraged to study the arts of their own cultural heritage and thereby gain self-esteem. Given that the study of Asia is required in many state curriculums, it is clear that our schools and teachers need support and resources to meet the demands and expectations that they already face.