Social Conformity and Nationalism in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning from Japan? Interpretations of Honda Motors by Strategic Management Theorists

Are cross-shareholdings of Japanese corporations dissolving? Evolution and implications MITSUAKI OKABE NISSAN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES NO. 33 2001 NISSAN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FULL LIST OF PAST PAPERS No.1 Yamanouchi Hisaaki, Oe Kenzaburô and Contemporary Japanese Literature. No.2 Ishida Takeshi, The Introduction of Western Political concepts into Japan. No.3 Sandra Wilson, Pro-Western Intellectuals and the Manchurian Crisis. No.4 Asahi Jôji, A New Conception of Technology Education in Japan. No.5 R John Pritchard, An Overview of the Historical Importance of the Tokyo War Trial. No.6 Sir Sydney Giffard, Change in Japan. No.7 Ishida Hiroshi, Class Structure and Status Hierarchies in Contemporary Japan. No.8 Ishida Hiroshi, Robert Erikson and John H Goldthorpe, Intergenerational Class Mobility in Post-War Japan. No.9 Peter Dale, The Myth of Japanese Uniqueness Revisited. No.10 Abe Shirô, Political Consciousness of Trade Union Members in Japan. No.11 Roger Goodman, Who’s Looking at Whom? Japanese, South Korean and English Educational Reform in Comparative Perspective. No.12 Hugh Richardson, EC-Japan Relations - After Adolescence. No.13 Sir Hugh Cortazzi, British Influence in Japan Since the End of the Occupation (1952-1984). No.14 David Williams, Reporting the Death of the Emperor Showa. No.15 Susan Napier, The Logic of Inversion: Twentieth Century Japanese Utopias. No.16 Alice Lam, Women and Equal Employment Opportunities in Japan. No.17 Ian Reader, Sendatsu and the Development of Contemporary Japanese Pilgrimage. No.18 Watanabe Osamu, Nakasone Yasuhiro and Post-War Conservative Politics: An Historical Interpretation. No.19 Hirota Teruyuki, Marriage, Education and Social Mobility in a Former Samurai Society after the Meiji Restoration. -

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master's

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Global Studies Jerónimo Arellano, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Sarah Mabry August 2018 Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Copyright by Sarah Mabry © 2018 Dedication Here I acknowledge those individuals by name and those remaining anonymous that have encouraged and inspired me on this journey. First, I would like to dedicate this to my great grandfather, Jerome Head, a surgeon, published author, and painter. Although we never had the opportunity to meet on this earth, you passed along your works of literature and art. Gleaned from your manuscript entitled A Search for Solomon, ¨As is so often the way with quests, whether they be for fish or buried cities or mountain peaks or even for money or any other goal that one sets himself in life, the rewards are usually incidental to the journeying rather than in the end itself…I have come to enjoy the journeying.” I consider this project as a quest of discovery, rediscovery, and delightful unexpected turns. I would like mention one of Jerome’s six sons, my grandfather, Charles Rollin Head, a farmer by trade and an intellectual at heart. I remember your Chevy pickup truck filled with farm supplies rattling under the backseat and a tape cassette playing Mozart’s piano sonata No. 16. This old vehicle metaphorically carried a hard work ethic together with an artistic sensibility. -

Molos Dimitrios 201212 Phd.Pdf (1.418Mb)

CULTURE, COMMUNITY AND THE MULTICULTURAL INDIVIDUAL Liberalism and the Challenge of Multiculturality by DIMITRIOS (JIM) MOLOS A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Philosophy in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada December, 2012 Copyright © Dimitrios (Jim) Molos, 2012 ABSTRACT Every theory of liberal multiculturalism is premised on some account of the nature of culture, cultural difference and social reality, or what I call “the conditions of multi- culturality”. In this dissertation, I offer a revised account of the conditions and challenge of multiculturality. Beginning with the widely accepted idea that individuals depend on both culture and community as social preconditions for choice, freedom and autonomy, and informing this idea with collectivist and individualist lessons from Tyler Burge’s famous externalist thought-experiment, my analysis shows that social contexts are multi- cultural when they are characterized by a plurality of social communities offering distinct sets of cultural norms, and individuals are multicultural to the extent that they are capable of using cultural norms from various social communities. The depth, pervasiveness, and complexity of multiculturality raises important normative questions about fair and just terms for protecting and promoting social communities under conditions of internal and external cultural contestation, and these questions are not only restricted to cases involv- ing internal minorities. As a theory of cultural justice, liberal multiculturalism must respond to the challenge of multiculturality generated by cultural difference per se, but it cannot do so adequately in all cases armed with only the traditional tools of toleration, freedom of association and exit, fundamental rights and freedoms, and internal political autonomy. -

Influencing Behavior During Planned Culture Change: a Participatory

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2016 Influencing Behavior During Planned Culture Change: A Participatory Action Research Case Study Michael Valentine Antioch University - PhD Program in Leadership and Change Follow this and additional works at: http://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons Recommended Citation Valentine, Michael, "Influencing Behavior During Planned Culture Change: A Participatory Action Research Case Study" (2016). Dissertations & Theses. 322. http://aura.antioch.edu/etds/322 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses at AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. INFLUENCING BEHAVIOR DURING PLANNED CULTURE CHANGE: A PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH CASE STUDY MICHAEL VALENTINE A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Ph.D. in Leadership and Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September, 2016 This is to certify that the Dissertation entitled: INFLUENCING BEHAVIOR DURING PLANNED CULTURE CHANGE: A PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH CASE STUDY prepared by Michael Valentine is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Leadership and Change. Approved by: Elizabeth Holloway, Ph.D., Chair date Mitchell Kusy, Ph.D., Committee Member date Ashley Lackovich-Van Gorp, Ph.D., Committee Member date Stephen A. -

Strong Cultures and Subcultures in Dynamic Organizations

02-091 The Role of Subcultures in Agile Organizations Alicia Boisnier Jennifer A. Chatman1 1 The second author wrote this paper while a Marvin Bower Fellow at the Harvard Business School and is grateful for their support. We also thank Elizabeth Mannix, Rita McGrath, and an anonymous reviewer for their insightful suggestions. Copyright © 2002 by Alicia Boisnier and Jennifer A. Chatman Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. The Role of Subcultures in Agile Organizations Alicia Boisnier and Jennifer A. Chatman1 Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley May 24, 2002 To appear in, R. Petersen and E. Mannix, Leading and managing people in dynamic organizations. Forthcoming, 2002. 1 The second author wrote this paper while a Marvin Bower Fellow at the Harvard Business School and is grateful for their support. We also thank Elizabeth Mannix, Rita McGrath, and an anonymous reviewer for their insightful suggestions. 2 Organizations face increasingly dynamic environments characterized by substantial, and often unpredictable technological, political, and economic change. How can organizations respond rapidly to such changes or become more agile? Organizational agility, according to Lee Dyer, “requires a judicious mix of stability and reconfigurability” (2001: 4). We consider an unlikely source of agility: organizational culture. This may seem like an odd juxtaposition since strong unitary cultures exert a stabilizing force on organizations by encouraging cohesion, organizational commitment, and desirable work behaviors among members (e.g., Deal & Kennedy, 1982; Nemeth & Staw, 1989; O'Reilly & Chatman, 1986). -

Proof That John Lennon Faked His Death

return to updates Proof that John Lennon Faked his Death Mark Staycer or John Lennon? by Miles Mathis This has been a theory from the very beginning, as most people know, but all the proof I have seen up to now isn't completely convincing. What we normally see is a lot of speculation about the alleged shooting in December of 1980. Many discrepancies have indeed been found, but I will not repeat them (except for a couple in my endnotes). I find more recent photographic evidence to be far easier and quicker to compile—and more convincing at a glance, as it were—so that is what I will show you here. All this evidence is based on research I did myself. I am not repeating the work of anyone else and I take full responsibility for everything here. If it appeals to you, great. If not, feel free to dismiss it. That is completely up to you, and if you don't agree, fine. When I say “proof” in my title, I mean it is proof enough for me. I no longer have a reasonable doubt. This paper wouldn't have been possible if John had stayed well hidden, but as it turns out he still likes to play in public. Being a bit of an actor, and always being confident is his ability to manipulate the public, John decided to just do what he wanted to do, covering it just enough to fool most people. This he has done, but he hasn't fooled me. The biggest clues come from a little indie film from Toronto about Lennon called Let Him Be,* released in 2009, with clips still up on youtube as of 2014. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

Romeo and Juliet from Multiple Critical Perspectives™

Multiple Critical Perspectives™ Teaching William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet from Multiple Critical Perspectives™ by Eva Richardson Multiple Critical Perspectives Romeo and Juliet Other titles in the Multiple Critical Perspective™ series include: 1984 Hamlet Our Town Animal Farm Heart of Darkness Picture of Dorian Gray, The Anthem House on Mango Street, The Pride and Prejudice Antigone I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Raisin in the Sun, A Awakening, The Importance of Being Earnest, The Richard III Brave New World Invisible Man (Ellison) Romeo and Juliet Catcher in the Rye, The Jane Eyre Scarlet Letter, The Comedy of Errors, The King Lear Separate Peace, A Crucible, The Life of Pi Siddhartha Cry, the Beloved Country Lord of the Flies Slaughterhouse-Five Death of a Salesman Macbeth Tale of Two Cities, A Doll’s House, A Merchant of Venice, The Taming of the Shrew, The Ethan Frome Metamorphosis, The Tempest, The Fahrenhiet 451 Midsummer Night’s Dream, A Things Fall Apart Frankenstein Much Ado About Nothing Things They Carried, The Grapes of Wrath, The Oedipus Rex To Kill a Mockingbird Great Expectations Of Mice and Men Twelfth Night Great Gatsby, The Old Man and the Sea, The Wuthering Heights P.O. Box 658, Clayton, DE 19938 www.prestwickhouse.com • 800.932.4593 ISBN 978-1-60389-441-8 Item No. 302929 Copyright 2008 Prestwick House, Inc. All rights reserved. No portion may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 P RESTWICK HOUSE , INC . Multiple Critical Romeo and Juliet Perspectives A Message to the Teacher of Literature P EN YOUR STUDENTS ’ EYES AND MINDS with this new, ex- Ociting approach to teaching literature. -

2 Culture and Culture Change

2 Culture and Culture Change CHAPTER SUMMARY The second chapter introduces us to culture. What is culture exactly? For most sociologists, culture refers to the knowledge, traditions, values, practices, and beliefs held by members of an organization, community, or society. As Eric Weissman describes, culture is a social force that impacts our daily lives and the choices we make. It can be both material and immaterial and produces “webs of significance” that influence both individual identity and entire societies. One distinction that you should take away from this chapter is that of culture versus structure. Structural elements of society are comprised of the enduring patterns of social relations and social institutions, whereas cultural elements are those that carry meanings. We interpret these meanings and attach them to certain values, ideas, and beliefs. In terms of time and space, culture can cover a vast area of meaning. It can refer to one’s entire social reality, or a particular social or geographical location. Even within Canada, when one thinks of Canadian culture, a few images immediately come to mind—the maple leaf and the game of hockey, for example. Yet within this one nationally unified culture, there exists several different cultures. These can be divided up by province, ethnicity, age, and so on. In terms of time and space, the other important distinction you must remember when looking at culture is that the culture of any people or place rarely stays the same over time. Culture is a fluid object and is always changing. Culture also influences the values and norms of a society. -

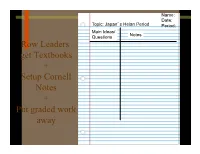

7.5 Heian Notes

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

Signaling Conformity: Changing Norms in Japan and China

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 27 Issue 3 2006 Signaling Conformity: Changing Norms in Japan and China David Nelken University of Macerata Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation David Nelken, Signaling Conformity: Changing Norms in Japan and China, 27 MICH. J. INT'L L. 933 (2006). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol27/iss3/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT SIGNALING CONFORMITY: CHANGING NORMS IN JAPAN AND CHINA David Nelken* The transnational circulation of people and ideas is transform- ing the world we live in, but grasping its full complexity is extraordinarilydifficult. It is essential to focus on specific places where transnationalflows are happening. The challenge is to study placeless phenomena in a place, to find small interstices in global processes in which critical decisions are made, to track the information flows that constitute global discourses, and to mark the points at which competing discourses intersect in the myriad links between global and local conceptions and institu- tions. -Sally Merry' In the current restructuring of world order, scholars of international and comparative law encounter unprecedented opportunities to offer in- sights into legal and social change, as well as to debate how such developments should best be regulated. -

A Comparative Study Between the Book Thief and Grave of the Fireflies from the Perspective of Trauma Narratives

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 10, No. 7, pp. 785-790, July 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1007.09 Who has Stolen Their Childhood?—A Comparative Study Between The Book Thief and Grave of the Fireflies from the Perspective of Trauma Narratives Manli Peng University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Yan Hua University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Abstract—Literature from the perspective of perpetrators receives less attention due to history and ethical problems, but it is our duty to view history as a whole. By comparing and analyzing The Book Thief and Grave of the Fireflies, this study claims that war and blind patriotism have stolen the childhood from the war-stricken children and that love, care, company and chances to speak out the pain can be the treatments. In the study, traumatic narratives, traumatic elements and treatments in both books are discussed comparatively and respectively. Index Terms—The Book Thief, Grave of the Fireflies, traumatic narratives, traumatic elements, treatments I. INTRODUCTION Markus Zusak's novel The Book Thief relates how Liesel Meminger, a little German girl, lost her beloved ones during the Second World War and how she overcame her miseries with love, friendship and the power of words. But The Book Thief is not just a Bildungsroman. According to Zusak, the inspiration of the book came from his parents, who witnessed a collection of Jews on their way to the death camps and the streetscape of Hamburg after the firebombing. The story “depicts the traumatic life experience of the German civilians and the hiding life of a Jew in the harsh situation of racial discrimination”(Chen, 2016, p.