2Nd Global Conference Music and Nationalism National Anthem Controversy and the ‘Spirit of Language’ Myth in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 27, folder “State Visits - Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 27 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN ~ . .,1. THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN A Profile On the Occasion of The Visit by The Emperor and Empress to the United States September 30th to October 13th, 1975 by Edwin 0. Reischauer The Emperor and Empress of japan on a quiet stroll in the gardens of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Few events in the long history of international relations carry the significance of the first visit to the United States of the Em peror and Empress of Japan. Only once before has the reigning Emperor of Japan ventured forth from his beautiful island realm to travel abroad. On that occasion, his visit to a number of Euro pean countries resulted in an immediate strengthening of the bonds linking Japan and Europe. -

Why Did Japan Industrialize During the Meiji Period? Objectives: Students Will Examine the Causes for Industrialization in Japan

Why did Japan end its isolation? Why did Japan industrialize during the Meiji Period? Objectives: Students will examine the causes for industrialization in Japan. Introduction Directions: Examine the two documents below and answer the questions that follow. Tokugawa Laws of Japan in 1634 * Japanese ships shall not be sent abroad. *No Japanese shall be sent abroad. Anyone breaking this law shall suffer the penalty of death... *The arrival of foreign ships must be reported to Edo (Tokyo) and a watch kept over them. *The samurai shall not buy goods on board foreign ships. Source: January 2002 Global History and Geography Regents Exam. Source: January 2002 Global History and Geography Regents Exam. Japan Opens Up Japan, under the rule of the Tokugawa clan (1603 to 1867), experienced more than 200 years of isolation. During this period, the emperors ruled in name only. The real political power was in the hands of the shoguns all of whom were from the Tokugawa family. The Tokugawa maintained a feudal system in Japan that gave them and wealthy landowners called daimyo power and control. After negative experiences with Europeans in the 1600s, the shoguns were extremely resistant to trade because they viewed outsiders as a threat to his power. Japan's isolation came to an end in 1853 when Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy, commanding a squadron of two steam ships and two sailing vessels, sailed into Tokyo harbor. He sought to force Japan to end their isolation and open their ports to trade with U.S merchant ships. At the time, many industrialized nations in Europe and the United States were seeking to open new markets where they could sell their manufactured goods, as well as new countries to supply raw materials for industry. -

The System of Trade Between Japan and the East European Countries, Including the Soviet Union

THE SYSTEM OF TRADE BETWEEN JAPAN AND THE EAST EUROPEAN COUNTRIES, INCLUDING THE SOVIET UNION YATARO TERADA* INTRODUCTION Poor in natural resources, Japan has long been dependent on overseas supply for most of her raw material and fuel requirements. While imports of raw materials and fuel by the United States and West Germany in 197o accounted respectively for 14 per cent and 22 per cent of their total imports, Japan's imports of raw materials and fuel in the same year amounted to about 59 per cent of her total imports. In addition, Japan depends on imports from foreign countries for ioo per cent of her wool, raw cotton, and nickel; 98 per cent of her petroleum; 95 per cent of her iron ores; and 55 per cent of her industrial coal. Such being the case, one of the guiding principles in Japan's foreign trade policy has been to expand trade with any country, regardless of its political system. Japan was plagued by a gap between her economic growth and her international balance of payments until the mid-i96o's and, in order to improve this situation, promotion of exports was given highest priority. Thus, efforts have been made to expand trade with the Soviet Union and East European countries on a commercial basis. After the resumption of private foreign trade in 1949, trade between Japan and the Soviet Union and East European countries was conducted at a low level for some time. However, since the conclusion of a treaty of commerce and an agree- ment on trade and payment with the Soviet Union in 1957, and the conclusion of treaties of commerce with Poland and Czechoslovakia in 1958 and 1959, Japan's trade with Eastern Europe has increased yearly. -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Tactics Are for Losers

Tactics are for Losers Military Education, The Decline of Rational Debate and the Failure of Strategic Thinking in the Imperial Japanese Navy: 1920-1941 A submission for the 2019 CN Essay Competition For Entry in the OPEN and DEFENCE Divisions The period of intense mechanisation and modernisation that affected all of the world’s navies during the latter half of the 19th and first half of the 20th century had possibly its greatest impact in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). Having been shocked into self- consciousness concerning their own vulnerability to modern firepower by the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry’s ‘Black Fleet’ at Edo bay on 8 July 1853, the state of Japan launched itself onto a trajectory of rapid modernisation. Between 1863 and 1920, the Japanese state transformed itself from a forgotten backwater of the medieval world to one of the world’s great technological and industrialised powers. The spearhead of this meteoric rise from obscurity to great power status in just over a half-century was undoubtedly the Imperial Japanese Navy, which by 1923 was universally recognised during the Washington Naval Conference as the world’s third largest and most powerful maritime force.1 Yet, despite the giant technological leaps forward made by the Imperial Japanese Navy during this period, the story of Japan’s and the IJN’s rise to great power status ends in 1945 much as it began during the Perry expedition; with an impotent government being forced to bend to the will of the United States and her allies while a fleet of foreign warships rested at anchor in Tokyo Bay. -

It Would Make No Sense for Article 9 to Mean What It Says, Therefore It Doesn’T

Volume 11 | Issue 39 | Number 2 | Article ID 4001 | Sep 29, 2013 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus It Would Make No Sense for Article 9 to Mean What it Says, Therefore It Doesn’t. The Transformation of Japan's Constitution 日本国憲法の変容 9条の文面は意味不明。しかるに文 字通り受け止めるべからず C. Douglas Lummis It should be done quietly. One day everybody woke up and found that the Weimar Constitution had been Nihonkoku Kenpo Kaisei Soan (Proposal for changed, replaced by the Nazi Amendment of the Constitution of Japan) Constitution. It changed without anyone noticing. Maybe we could Central Office for the Promotion of learn from that. No hullabaloo. Constitutional Reform: Drafting Committee The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan Aso was bombarded with criticism from within Japan and from around the world, from people 27 April, 2012 shocked to learn that there is a political leader Nihonkoku Kenpo Kaisei Soan: Q&A (Proposal in a major democratic country who could for Amendment of the Constitution of Japan: confess to believing that something useful Q&A) about how to deal with democratic constitutions can be learned from the Nazi Central Office for the Promotion ofexample. After a couple of days, he “retracted” Constitutional Reform the statement. Trouble is, you can’t talk the cat back into the bag once you’ve let it out. And The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan also, if you make a statement that reveals your dreadful ignorance (The Weimar Constitution October, 2012 was never amended by the Nazis; the Nazis did not take over the government “quietly”) There is a rumor in Japan that Aso Taro, former retracting it will not persuade people that you Prime Minister and present Deputy Prime weren’t so ignorant after all. -

Abenomics' Effect on Gender Inequality in Japanese Society And

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Honors College Theses 2021 Abenomics’ Effect on Gender Inequality in Japanese Society and the Workplace Arianna C. Johnson Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Japanese Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Arianna C., "Abenomics’ Effect on Gender Inequality in Japanese Society and the Workplace" (2021). Honors College Theses. 583. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/583 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abenomics’ Effect on Gender Inequality in Japanese Society and the Workplace An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Political Science and International Studies. By Arianna C. Johnson Under the mentorship of Dr. Christopher M. Brown ABSTRACT In this study, I determine the extent to which Japan’s shrinking workforce population has been affected by gender roles. Many Asian countries are experiencing a prominent decline in birth rate and population, which has increased global interest in these issues. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Japanese government officials have eagerly responded, pushing Japanese women into the labor force as a possible solution. However, this decision has unanticipated drawbacks, which requires officials to address Japanese women’s concerns in and outside of the workplace. I argue that the Japanese government will have more success by addressing these needs, creating a more gender-equal society for Japanese women. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

7.5 Heian Notes

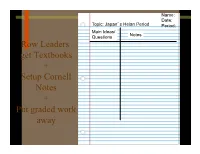

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

Japan Imperial Institution: Discourse and Reality of Political and Social Ideology

Volume 3, Issue 10, October– 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 Japan Imperial Institution: Discourse and Reality of Political and Social Ideology Reihani Suci Budi Utami I Ketut Surajaya Under graduate student Japanese Studies Program Professor of History, Department of History, Faculty of Humanities University Indonesia, Depok 16424, Japanese Studies Program Faculty of Humanities University Indonesia Indonesia, Depok 16424, Indonesia Abstract:- This study discussed the position and role of state slogan Fukoku Kyouhei(Strong Military Rich State) the Emperor based on two Constitutions that have been proclaimed by Meiji government. and are in force in Japan, namely the Meiji Constitution and the 1947 Constitution. The focus of this study was to The Japan State Constitution, passed in 1946 and describe Articles governing the position and role of the implemented in 1947, was compiled during the American Emperor in Japanese government are implemented. The Occupation under General Douglas MacArthur. Democracy study found that articles governing the position of and peace were the ideological foundation of the 1947 Emperor in the Meiji Constitution were not properly Constitution. The Imperial Institution was separated from implemented due to military domination in the the State institutions that run the Government. The position government. Emperor Hirohito in reality did not have of the Emperor as symbol of State union shall not interfere full power in carrying out his functions according to the in administration affairs of the Government. institution. Articles governing the position and function of the Emperor in the 1947 Constitution are proper. In the Meiji Constitution, the Emperor was a Head of Emperor Hirohito, who was later replaced by Prince State who had wide prerogative rights. -

Financial Crime

Japan’s Shifting Geopolitical and Geo-economic relations in Africa A view from Japan Inc. By Dr Martyn Davies, Managing Director: Emerging Markets & Africa, Frontier Advisory Deloitte and Kira McDonald, Research Analyst, Frontier Advisory Deloitte The Japanese translation was published in changer” in Africa since the turn of the century; Building Hitotsubashi Business Review geopolitical stature and influence in Africa with a (Vol. 63, No. 1, June 2015, pp. 24-41). potential view toward gaining a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC); and the strategic Introduction need for securing resource assets with special emphasis on energy resources and key metals for its industrial Japan has been grappling with defining its Africa economy.1 strategy. Historically, Japanese engagement with Since 2000, Japan’s strategy toward Africa has begun Africa has emphasised aid and development rather to shift. Whereas previously the relationship was than focused pragmatic commercial interest. Japan’s characterised by a donor-recipient model to a more engagement in Africa is seen as benign due in large part commercially-orientated approach, encouraging to its non-involvement in the continent’s colonial history. development through private investment, and However, Japan’s engagement of Africa is undergoing a incorporating a greater focus on business aligned shift due in large part by the increased prominence of the to the interests of Japan Inc. But as Africa itself is African continent and rising competition from emerging rapidly changing, so too much the foreign policy and actors who this century are rapidly accumulating both commercial strategy of Japan toward the continent. geopolitical and geo-economic capital on the continent. -

Download the Publication

A TIME FOR CHANGE? JAPAN’S “PEACE” CONSTITUTION AT 65 Edited by Bryce Wakefield Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org Photo: A supporter of Article 9 protests outside the National Diet of Japan. The sign reads: “Don’t change Article 9!” © 2006 Bryce Wakefield ISBN: 978-1-938027-98-7 ©2012 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. www.wilsoncenter.org The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars is the national, living memorial honoring President Woodrow Wilson. In provid- ing an essential link between the worlds of ideas and public policy, the Center addresses current and emerging challenges confronting the United States and the world. The Center promotes policy-relevant research and dialogue to in- crease understanding and enhance the capabilities and knowledge of leaders, citizens, and institutions worldwide. Created by an Act of Congress in 1968, the Center is a nonpartisan institution headquartered in Washington, D.C., and sup- ported by both public and private funds. Jane Harman, President, CEO and Director Board of Trustees: Joseph B. Gildenhorn, Chair; Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chair Public Members: Hon. James H. Billington, Librarian of Congress; Hillary R. Clinton, Secretary, U.S. Department of State; G. Wayne Clough, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution; Arne Duncan, Secretary, U.S. Department of Education; David Ferriero, Archivist of the United States; James Leach, Chairman, National Endowment for the Humanities; Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Private Citizen Members:Timothy Broas, John Casteen, Charles Cobb, Jr., Thelma Duggin, Carlos M.