Portugal : Health System Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mundial.Com Navegantecultural

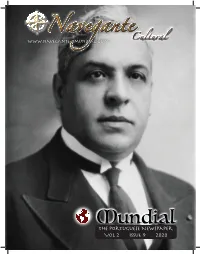

This is your outside front cover (OFC). The red line is the bleed area. www.navegante-omundial.com NaveganteCultural MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Vol 2 Issue 9 2020 This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. Letter from the Editor MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Aristides de Sousa One of those measures was the right of refusal Mendes saved the for consular officials to grant or issue Visas, set PUBLISHER / EDITORA lives of thousands first in Circular Number 10, and reinforced a Navegante Cultural Navigator of Jews fleeing the year later by Circular Number 14 in 1939. 204.981.3019 Nazis during his tenure as Portuguese At the same time, in reaction to the Consul in Bordeaux, Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany, in early EDITOR-IN-CHIEF France. -

Contradictions of the Estado Novo in the Modernisation of Portugal: Design and Designers in the 1940'S and 50'S

“Design Policies: Between Dictatorship and Resistance” | December 2015 Edition CONTRADICTIONS OF THE ESTADO NOVO IN THE MODERNISATION OF PORTUGAL: DESIGN AND DESIGNERS IN THE 1940'S AND 50'S Helena Barbosa, Universidade de Aveiro ABSTRACT The period of Portuguese history known as the Estado Novo (1933-1974) presents a series of contradictions as regards the directives issued, possibly resulting from a lack of political cohesion. Considering the dichotomy between modernization and tradition that existed between the 1940s and ‘50s, and the obvious validity of the government’s actions, this paper aims to demonstrate the contradictory attitudes towards the modernization of the country via different routes, highlighting the role of ‘designers’ as silent interlocutors and agents of change in this process. Various documents are analysed, some published under the auspices of the Estado Novo, others in the public sphere, in order to reveal the various partnerships that were in operation and the contrasting attitudes towards the government at the time. Other activities taking place in the period are also analysed, both those arising from state initiatives and others that were antithetical to it. The paper reveals the need to break with the political power in order to promote artistic and cultural interests, and describes initiatives designed to promote industry in the country, some launched by the Estado Novo, others by companies. It focuses upon the teaching of art, which later gave rise to the teaching of design, and on the presence of other institutions and organizations that contributed to the modernization of Portugal, in some cases by mounting exhibitions in Portugal and abroad, as well as other artistic activities such as graphic design, product design and interior decoration, referring to the respective designers, artefacts and spaces. -

Portugal's History Since 1974

Portugal’s history since 1974 Stewart Lloyd-Jones ISCTE-Lisbon AN IMPERIAL LEGACY The Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos) that broke out on the morning of 25 April 1974 has had a profound effect on Portuguese society, one that still has its echoes today, almost 30 years later, and which colours many of the political decision that have been, and which continue to be made. During the authoritarian regime of António de Oliveira Salazar (1932-68) and his successor, Marcello Caetano (1968-74), Portugal had existed in a world of its own construction. Its vast African empire (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé e Príncipe, and Cape Verde) was consistently used to define Portugal’s self-perceived identity as being ‘in, but not of Europe’. Within Lisbon’s corridors of power, the dissolution of the other European empires was viewed with horror, and despite international opprobrium and increasing isolation, the Portuguese dictatorship was in no way prepared to follow the path of decolonisation. As Salazar was to defiantly declare, Portugal would stand ‘proudly alone’, indeed, for a regime that had consciously legitimated itself by ‘turning its back on Europe’, there could be no alternative course of action. Throughout the 1960s and early-1970s, the Portuguese people were to pay a high price for the regime’s determination to remain in Africa. From 1961 onwards, while the world’s attention was focused on events in south-east Asia, Portugal was fighting its own wars. By the end of the decade, the Portuguese government was spending almost half of its GNP on sustaining a military presence of over 150,000 troops in Africa. -

International Literary Program

PROGRAM & GUIDE International Literary Program LISBON June 29 July 11 2014 ORGANIZATION SPONSORS SUPPORT GRÉMIO LITERÁRIO Bem-Vindo and Welcome to the fourth annual DISQUIET International Literary Program! We’re thrilled you’re joining us this summer and eagerly await meeting you in the inimitable city of Lisbon – known locally as Lisboa. As you’ll soon see, Lisboa is a city of tremendous vitality and energy, full of stunning, surprising vistas and labyrinthine cobblestone streets. You wander the city much like you wander the unexpected narrative pathways in Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, the program’s namesake. In other words, the city itself is not unlike its greatest writer’s most beguiling text. Thanks to our many partners and sponsors, traveling to Lisbon as part of the DISQUIET program gives participants unique access to Lisboa’s cultural life: from private talks on the history of Fado (aka The Portuguese Blues) in the Fado museum to numerous opportunities to meet with both the leading and up-and- coming Portuguese authors. The year’s program is shaping up to be one of our best yet. Among many other offerings we’ll host a Playwriting workshop for the first time; we have a special panel dedicated to the Three Marias, the celebrated trio of women who collaborated on one of the most subversive books in Portuguese history; and we welcome National Book Award-winner Denis Johnson as this year’s guest writer. Our hope is it all adds up to a singular experience that elevates your writing and affects you in profound and meaningful ways. -

C U L T U R a , E S P a Ç O & M E M Ó R Ia

5 0 - 7 9 5 0 1 - 2 8 1 2 : N S S I a N.º 5 | 2014 i r ó m CEM e cultura, espaço & memória m Revista do CITCEM & – CENTRO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO TRANSDISCIPLINAR o CULTURA, ESPAÇO & MEMÓRIA ç « » a p s e Neste Número: , a DOSSIER TEMÁTICO r «População e Saúde» u (eds. Jorge Fernandes Alves t e Carlota Santos) l u RECENSÕES c NOTÍCIAS M E C CITCEM centro de investigação transdisciplinar CITCEM cultura, espaço e memória CEM N.º 5 cultura, espaço & memória CEM N.º 5 CULTURA, ESPAÇO & MEMÓRIA Edição: CITCEM – Centro de Investigação Transdisci- plinar «Cultura, Espaço & Memória» (Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto/Universidade do Minho)/Edições Afrontamento Directora: Maria Cristina Almeida e Cunha Editores do dossier temático: Jorge Fernandes Alves | Carlota Santos Foto da capa: Paisagem minhota, 2013. Foto de Arlindo Alves. Colecção particular.. Design gráfico: www.hldesign.pt Composição, impressão e acabamento: Rainho & Neves, Lda. Distribuição: Companhia das Artes N.º de edição: 1604 Tiragem: 500 exemplares Depósito Legal: 321463/11 ISSN: 2182-1097-05 Periodicidade: Anual Esta revista tem edição online que respeita os critérios do OA (open access). Outubro de 2014 Este trabalho é financiado por Fundos Nacionais através da FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia no âmbito do projecto PEst-OE/HIS/UI4059/2014 EDITORIAL pág. 5 «EM PROL DO BEM COMUM»: O VARIA CONTRIBUTO DA LIGA PORTUGUESA DE SOB O OLHAR DA CONSTRUÇÃO DA APRESENTAÇÃO PROFILAXIA SOCIAL PARA A EDUCAÇÃO MEMÓRIA:RICARDO JORGE NA TRIBUNA HIGIÉNICA NO PORTO (1924-1960) DA HISTÓRIA POPULAÇÃO E SAÚDE I Ismael Cerqueira Vieira pág. -

Portuguese Economic Growth, 1527-1850 Nuno Palma

European Historical Economics Society EHES WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY | NO. 137 From Convergence to Divergence: Portuguese Economic Growth, 1527-1850 Nuno Palma (University of Manchester and CEPR) Jaime Reis (Universidade de Lisboa) AUGUST 2018 EHES Working Paper | No. 137|August 2018 From Convergence to Divergence: Portuguese Economic Growth, 1527-1850* Nuno Palma1 (University of Manchester and CEPR) Jaime Reis2 (Universidade de Lisboa) Abstract We construct the first time-series for Portugal’s per capita GDP for 1527-1850, drawing on a new database. Starting in the early 1630s there was a highly persistent upward trend which accelerated after 1710 and peaked 40 years later. At that point, per capita income was high by European standards, though behind the most advanced Western European economies. But as the second half of the eighteenth century unfolded, a phase of economic decline was initiated. This continued into the nineteenth century, and by 1850 per capita incomes were not different from what they had been in the early 1530s. JEL Classification: N13, O52 Keywords: Early Modern Portugal, Historical National Accounts, Standards of Living Debate, the Little Divergence, Malthusian Model. ∗ Acknowledgments: We are grateful to Steve Broadberry, Leonor F. Costa, António C. Henriques, Kivanç Karaman, Wolfgang Keller, Cormac Ó Gráda, Şevket Pamuk, Leandro Prados de la Escosura, Joan R. Rosés, Jacob Weisdorf, Jeffrey Williamson, and many participants at the Nova SBE lunchtime seminar, the 2014 Accounting for the Great Divergence conference, The University of Warwick in Venice, the 2014 APHES conference in Lisbon, and the 2015 EHES in Pisa for discussion of this paper. We also thank colleagues on the Prices, Wages and Rents in Portugal 1300-1910 project. -

001 224 ING Final LM.Indd 1 15/01/15 09:18 Editor Published by Lord Nigel Crisp Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Av

The Future for Health everyone has a role to play 001_224 ING Final_LM.indd 1 15/01/15 09:18 Editor PublishEd by Lord Nigel Crisp Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Av. de Berna 45 A Editing Coordinator 1067-001 Lisbon Cristina Monteiro Portugal Tel. (+351 21 782 3000) Design TVM Designers Email: [email protected] http://www.gulbenkian.pt Printing Gráfica Maiadouro, S.A. ©Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation 2014 For further information on the Print run Future for Health Gulbenkian Platform, 300 copies or to download the original report, please visit: www.gulbenkian.pt Or contact: ISBN 978-989-8380-17-3 Gulbenkian Programme for Innovation in Health LegaL DepoSIt 379 935/14 [email protected] 001_224 ING Final_LM.indd 2 15/01/15 09:18 The Future for Health everyone has a role to play Lord Nigel Crisp (Chair) Donald Berwick Ilona Kickbusch Wouter Bos João Lobo Antunes Pedro Pita Barros Jorge Soares COLLABORATION: 001_224 ING Final_LM.indd 3 15/01/15 09:18 Foreword from the President of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation the heaLth of the portugueSe popuLatIoN has made a remarkable progress in the last few decades, a fact that was recognized internationally and is the most positive achievement of our forty-year democratic regime. However we cannot ignore the limitations of our resources and how it affects our options. We are well aware of the need to prioritize our problems and the allocation of our resources. We must decide wisely, with boldness and courage. The progress achieved in the health system is due to enlightened policies but also to scientific advances and technological innovation. -

Gender Transformations

Edited by: JULIA KATHARINA KOCH, WIEBKE KIRLEIS GENDER TRANSFORMATIONS in Prehistoric and Archaic Societies This is a free offprint – as with all our publications the entire book is freely accessible on our website, and is available in print or as PDF e-book. www.sidestone.com Edited by: JULIA KATHARINA KOCH, WIEBKE KIRLEIS GENDER TRANSFORMATIONS in Prehistoric and Archaic Societies Scales of Transformation I 06 © 2019 Individual authors Published by Sidestone Press, Leiden www.sidestone.com Imprint: Sidestone Press Academics All articles in this publication have peen peer-reviewed. For more information see www.sidestone.nl Layout & cover design: CRC 1266/Carsten Reckweg and Sidestone Press Cover images: Carsten Reckweg. – In the background a photo of the CRC1266-excavation of a Bronze Age burial mound near Bornhöved (LA117), Kr. Segeberg, Germany, in summer/autumn 2018. The leadership was taken over by 2 women, the team also included 10 women and 11 men, of whom the female staff were present for a total of 372 days and the male for 274 days. Text editors: Julia Katharina Koch and Suzanne Needs-Howarth ISSN 2590-1222 ISBN 978-90-8890-821-7 (softcover) ISBN 978-90-8890-822-4 (hardcover) ISBN 978-90-8890-823-1 (PDF e-book) The STPAS publications originate from or are involved with the Collaborative Research Centre 1266, which is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation; Projektnummer 2901391021 – SFB 1266). Preface of the series editors With this book series, the Collaborative Research Centre Scales of Transformation: Human-Environmental Interaction in Prehistoric and Archaic Societies (CRC 1266) at Kiel University enables the bundled presentation of current research outcomes of the multiple aspects of socio-environmental transformations in ancient societies. -

2010-Portugueses-Em-Dic3a1spora

POPULAÇÃO E SOCIEDADE Dinâmicas e Perspectivas Demográficas do Portugal Contemporâneo CEPESE Título Adriano Moreira – Academia das Ciências de Lisboa POPULAÇÃO E SOCIEDADE – n.º 18 / 2010 Amadeu Carvalho Homem – Universidade de Coimbra Ramon Villares – Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Edição Ismênia Martins – Universidade Federal Fluminense CEPESE – Centro de Estudos da População, Economia e Sociedade / Lorenzo Lopez Trigal – Universidade de Leon Edições Afrontamento Lená Medeiros de Menezes – Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Rua do Campo Alegre, 1055 – 4169-004 PORTO Gladys Ribeiro – Universidade Federal Fluminense Telef.: 22 609 53 47 Haluk Gunugur – Universidade Bilkent Fax: 22 543 23 68 Maria del Mar Lousano Bartolozzi – Universidade de Extremadura E-mail: [email protected] David Reher – Universidade Complutense de Madrid http://cepese.pt Philippe Poirrier – Universidade de Borgonha Hipolito de la Tórre Gomez – UNED – Universidade Nacional Edições Afrontamento de Educação à Distância Rua de Costa Cabral, 859 – 4200-225 PORTO Patrícia Alejandra Fogelman – Instituto Ravingani, UBA Telef.: 22 507 42 20 Angelo Trento – Universidade de Napoli Fax: 22 507 42 29 Matteo Sanfilippo – Universidade de Tuscia – Viterbo E-mail: [email protected] Jan Sundin – Universidade de Linköping www.edicoesafrontamento.pt Jonathan Riley-Smith – Universidade de Cambridge Manuel Gonzalez Jimenez – Universidade de Sevilha Fundadores Jean-Philippe Genet – Universidade Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 Universidade do Porto Neil Gilbert – Universidade de Berkeley, California Fundação Eng. António de Almeida James Newell – Universidade de Salford Fernando de Sousa – Universidade do Porto, Universidade Lusíada Renato Flores – Fundação Getúlio Vargas do Porto J. Manuel Nazareth – Universidade Nova de Lisboa Coordenadora do Dossier Temático Jorge Arroteia – Universidade de Aveiro Maria João Guardado Directora Design Maria da Conceição Meireles Pereira João Machado Comissão Editorial Execução Gráfica Rainho & Neves, Lda. -

Anglo Saxonica III N. 3

REVISTA ANGLO SAXONICA SER. III N. 3 2012 A NNGLO SAXO ICA ANGLO SAXONICA SER. III N. 3 2012 DIRECÇÃO / GENERAL EDITORS Isabel Fernandes (ULICES) João Almeida Flor (ULICES) Mª Helena Paiva Correia (ULICES) COORDENAÇÃO / EXECUTIVE EDITOR Teresa Malafaia (ULICES) EDITOR ADJUNTO / ASSISTANT EDITOR Ana Raquel Lourenço Fernandes (ULICES) CO-EDITOR ADJUNTO / CO-EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Sara Paiva Henriques (ULICES) REVISÃO DE TEXTO / COPY EDITORS Inês Morais (ULICES) Madalena Palmeirim (ULICES) Ana Luísa Valdeira (ULICES) EDIÇÃO Centro de Estudos Anglísticos da Universidade de Lisboa DESIGN, PAGINAÇÃO E ARTE FINAL Inês Mateus IMPRESSÃO E ACABAMENTO Várzea da Rainha Impressores, S.A. - Óbidos, Portugal TIRAGEM 150 exemplares ISSN 0873-0628 DEPÓSITO LEGAL 86 102/95 PUBLICAÇÃO APOIADA PELA FUNDAÇÃO PARA A CIÊNCIA E A TECNOLOGIA New Directions in Translation Studies Special Issue of Anglo Saxonica 3.3 Guest Editors: Anthony Pym and Alexandra Assis Rosa Novos Rumos nos Estudos de Tradução Número Especial da Anglo Saxonica 3.3 Editores convidados: Anthony Pym e Alexandra Assis Rosa CONTENTS/ÍNDICE NEW DIRECTIONS IN TRANSLATION INTRODUCTION Anthony Pym and Alexandra Assis Rosa . 11 LITERARY TRANSLATION TRUSTING TRANSLATION João Ferreira Duarte . 17 ANTHOLOGIZING LATIN AMERICAN LITERATURE: SWEDISH TRANSLATIVE RE-IMAGININGS OF LATIN AMERICA 1954-1998 AND LINKS TO TRAVEL WRITING Cecilia Alvstad . 39 THE INTERSECTION OF TRANSLATION STUDIES AND ANTHOLOGY STUDIES Patricia Anne Odber de Baubeta . 69 JOSÉ PAULO PAES — A PIONEERING BRAZILIAN THEORETICIAN John Milton . 85 TRANSLATION AND LITERATURE AGAIN: RECENT APPROACHES TO AN OLD ISSUE Maria Eduarda Keating . 101 UNDER THE SIGN OF JANUS: REFLECTIONS ON AUTHORSHIP AS LIMINALITY IN . TRANSLATED LITERATURE Alexandra Lopes . 127 TRANSLATED AND NON-TRANSLATED SPANISH PICARESQUE NOVELS IN DEFENSE OF . -

Dom Manuel II of Portugal. Russell Earl Benton Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1975 The oD wnfall of a King: Dom Manuel II of Portugal. Russell Earl Benton Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Benton, Russell Earl, "The oD wnfall of a King: Dom Manuel II of Portugal." (1975). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2818. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2818 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that die photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

New and Old Routes of Portuguese Emigration

IMISCOE Research Series Cláudia Pereira Joana Azevedo Editors New and Old Routes of Portuguese Emigration Uncertain Futures at the Periphery of Europe IMISCOE Research Series This series is the official book series of IMISCOE, the largest network of excellence on migration and diversity in the world. It comprises publications which present empirical and theoretical research on different aspects of international migration. The authors are all specialists, and the publications a rich source of information for researchers and others involved in international migration studies. The series is published under the editorial supervision of the IMISCOE Editorial Committee which includes leading scholars from all over Europe. The series, which contains more than eighty titles already, is internationally peer reviewed which ensures that the book published in this series continue to present excellent academic standards and scholarly quality. Most of the books are available open access. For information on how to submit a book proposal, please visit: http://www. imiscoe.org/publications/how-to-submit-a-book-proposal. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/13502 Cláudia Pereira • Joana Azevedo Editors New and Old Routes of Portuguese Emigration Uncertain Futures at the Periphery of Europe Editors Cláudia Pereira Joana Azevedo Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Investigação e (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (CIES-IUL) Estudos de Sociologia (CIES-IUL) Observatório da Emigração Observatório da Emigração Lisbon, Portugal Lisbon, Portugal ISSN 2364-4087 ISSN 2364-4095 (electronic) IMISCOE Research Series ISBN 978-3-030-15133-1 ISBN 978-3-030-15134-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15134-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019.