A History of Portuguese Economic Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mundial.Com Navegantecultural

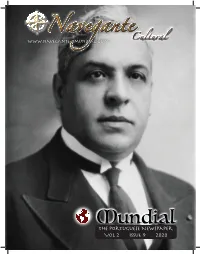

This is your outside front cover (OFC). The red line is the bleed area. www.navegante-omundial.com NaveganteCultural MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Vol 2 Issue 9 2020 This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. Letter from the Editor MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Aristides de Sousa One of those measures was the right of refusal Mendes saved the for consular officials to grant or issue Visas, set PUBLISHER / EDITORA lives of thousands first in Circular Number 10, and reinforced a Navegante Cultural Navigator of Jews fleeing the year later by Circular Number 14 in 1939. 204.981.3019 Nazis during his tenure as Portuguese At the same time, in reaction to the Consul in Bordeaux, Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany, in early EDITOR-IN-CHIEF France. -

Lucas on the Relationship Between Theory and Ideology

Discussion Paper No. 2010-28 | November 17, 2010 | http://www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/discussionpapers/2010-28 Lucas on the Relationship between Theory and Ideology Michel De Vroey IRES, University of Louvain Please cite the corresponding journal article: http://dx.doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2011-4 Abstract This paper concerns a neglected aspect of Lucas’s work: his methodological writings, published and unpublished. Particular attention is paid to his views on the relationship between theory and ideology. I start by setting out Lucas’s non-standard conception of theory: to him, a theory and a model are the same thing. I also explore the different facets and implications of this conception. In the next two sections, I debate whether Lucas adheres to two methodological principles that I dub the ‘non-interference’ precept (the proposition that ideological viewpoints should not influence theory), and the ‘non-exploitation’ precept (that the models’ conclusions should not be transposed into policy recommendations, in so far as these conclusions are built into the models’ premises). The last part of the paper contains my assessment of Lucas’s ideas. First, I bring out the extent to which Lucas departs from the view held by most specialized methodologists. Second, I wonder whether the new classical revolution resulted from a political agenda. Third and finally, I claim that the tensions characterizing Lucas’s conception of theory follow from his having one foot in the neo- Walrasian and the other in the Marshallian–Friedmanian universe. JEL B22, B31, B41, E30 Keywords Lucas; new classical macroeconomics; methodology Correspondence Michel De Vroey, IRES, University of Louvain, Place Montesquieu 3, B- 3458 Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: e-mail: [email protected] A first version of this paper was presented at seminars given at the University of Toronto and the University of British Columbia. -

Contradictions of the Estado Novo in the Modernisation of Portugal: Design and Designers in the 1940'S and 50'S

“Design Policies: Between Dictatorship and Resistance” | December 2015 Edition CONTRADICTIONS OF THE ESTADO NOVO IN THE MODERNISATION OF PORTUGAL: DESIGN AND DESIGNERS IN THE 1940'S AND 50'S Helena Barbosa, Universidade de Aveiro ABSTRACT The period of Portuguese history known as the Estado Novo (1933-1974) presents a series of contradictions as regards the directives issued, possibly resulting from a lack of political cohesion. Considering the dichotomy between modernization and tradition that existed between the 1940s and ‘50s, and the obvious validity of the government’s actions, this paper aims to demonstrate the contradictory attitudes towards the modernization of the country via different routes, highlighting the role of ‘designers’ as silent interlocutors and agents of change in this process. Various documents are analysed, some published under the auspices of the Estado Novo, others in the public sphere, in order to reveal the various partnerships that were in operation and the contrasting attitudes towards the government at the time. Other activities taking place in the period are also analysed, both those arising from state initiatives and others that were antithetical to it. The paper reveals the need to break with the political power in order to promote artistic and cultural interests, and describes initiatives designed to promote industry in the country, some launched by the Estado Novo, others by companies. It focuses upon the teaching of art, which later gave rise to the teaching of design, and on the presence of other institutions and organizations that contributed to the modernization of Portugal, in some cases by mounting exhibitions in Portugal and abroad, as well as other artistic activities such as graphic design, product design and interior decoration, referring to the respective designers, artefacts and spaces. -

The Neglect of the French Liberal School in Anglo-American Economics: a Critique of Received Explanations

The Neglect of the French Liberal School in Anglo-American Economics: A Critique of Received Explanations Joseph T. Salerno or roughly the first three quarters of the nineteenth century, the "liberal school" thoroughly dominated economic thinking and teaching in F France.1 Adherents of the school were also to be found in the United States and Italy, and liberal doctrines exercised a profound influence on prominent German and British economists. Although its numbers and au- thority began to dwindle after the 1870s, the school remained active and influential in France well into the 1920s. Even after World War II, there were a few noteworthy French economists who could be considered intellectual descendants of the liberal tradition. Despite its great longevity and wide-ranging influence, the scientific con- tributions of the liberal school and their impact on the development of Eu- ropean and U.S. economic thought—particularly on those economists who are today recognized as the forerunners, founders, and early exponents of marginalist economics—have been belittled or simply ignored by most twen- tieth-century Anglo-American economists and historians of thought. A number of doctrinal scholars, including Joseph Schumpeter, have noted and attempted to explain the curious neglect of the school in the En- glish-language literature. In citing the school's "analytical sterility" or "indif- ference to pure theory" as a main cause of its neglect, however, their expla- nations have overlooked a salient fact: that many prominent contributors to economic analysis throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries expressed strong appreciation of or weighty intellectual debts to the purely theoretical contributions of the liberal school. -

Curriculum Vitae June, 2021

Curriculum Vitae June, 2021 Assist. Prof. Sergio Angeli Affiliation Faculty of Science and Technology Free University of Bozen-Bolzano Piazza Università 1, 39100, Bolzano, Italy Email: [email protected] Current position Tenured Assistant Professor of General and Applied Entomology and Apiculture at the Faculty of Science and Technology, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy, since June 2009. Departmental and Institutional Coordinator for the Erasmus Programs for the Free University of Bozen- Bolzano, Italy with the promotion of 5 bilateral agreements: University of Göttingen (Germany), University of Cape Coast (Ghana), University of Chiang Mai (Thailand), Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Sweden) and University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences of Vienna (Austria). Member of the Scientific Council of the PhD School “Mountain Environment and Agriculture”, Faculty of Science and Technology, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano (Italy) since 2009. Member of the Study Council of the Master Program “International Horticultural Science”, Join Master of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano and the University of Bologna (Italy) since 2009. Member of the Municipal Council of Croviana, Trento province, Italy. Elected for the period 01/06/2010 - 01/06/2015, confirmed for the period 01/06/2015 - 20/10/2020 and for the period 20/10/2020 - 20/10/2025. Personal data Birthday: 11 July 1972; Place of birth: Cles (TN), Italy; Nationality: Italian; Marital status: married, 1 child. Education and Academic Career • Assistant Professor Department of Forest Zoology and Forest Conservation, Göttingen 2004 – 2009 (5 years) University, Germany. • Assistant Professor Institute of General and Systematic Zoology, Giessen University, 2002 – 2004 (2 years) Germany. -

Firmin Oulès and the “New Lausanne School”

Firmin Oulès and the "New Lausanne School" David Sarech (University of Lausanne, Ph.D. Student) In this paper I will present Firmin Oulès’ “harmonized economics” and interrogate the relationship between state and market in his thought. “Harmonized economics” were conceived as the continuation of Léon Walras’ theory. The key concept of the first Lausanne school is the notion of equilibrium. Indeed, Walras forged it in order to “scientifically” demonstrate the superiority of a competition-based economy. However, the mathematical approach he chose, as well as his disdain for the orthodox economy of his time, led him to be misunderstood and he did not receive the recognition he was expecting. Thus the concept of general equilibrium would be forgotten until the mid 1950’s when it would become the core of microeconomics. However, as recent studies in history of economic thought have shown, the concept of equilibrium in Walras’ thought has to be understood in a broader context than a purely economical one. Indeed, the main goal of Walras was to bring an answer to “the social question”. Contrary to Marx, he did not think of it as being a problem of profit distribution between labor and capital. Instead he thought the goal of the economist was to create an economic system were everyone would be able to exert its inner abilities and in which inequalities would be based solely on merit. The incentive created by private property and profit-seeking being the groundwork of a flourishing economy, the equilibrium had to be understood as a tool to establish this idealistic society. -

Portugal's History Since 1974

Portugal’s history since 1974 Stewart Lloyd-Jones ISCTE-Lisbon AN IMPERIAL LEGACY The Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos) that broke out on the morning of 25 April 1974 has had a profound effect on Portuguese society, one that still has its echoes today, almost 30 years later, and which colours many of the political decision that have been, and which continue to be made. During the authoritarian regime of António de Oliveira Salazar (1932-68) and his successor, Marcello Caetano (1968-74), Portugal had existed in a world of its own construction. Its vast African empire (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé e Príncipe, and Cape Verde) was consistently used to define Portugal’s self-perceived identity as being ‘in, but not of Europe’. Within Lisbon’s corridors of power, the dissolution of the other European empires was viewed with horror, and despite international opprobrium and increasing isolation, the Portuguese dictatorship was in no way prepared to follow the path of decolonisation. As Salazar was to defiantly declare, Portugal would stand ‘proudly alone’, indeed, for a regime that had consciously legitimated itself by ‘turning its back on Europe’, there could be no alternative course of action. Throughout the 1960s and early-1970s, the Portuguese people were to pay a high price for the regime’s determination to remain in Africa. From 1961 onwards, while the world’s attention was focused on events in south-east Asia, Portugal was fighting its own wars. By the end of the decade, the Portuguese government was spending almost half of its GNP on sustaining a military presence of over 150,000 troops in Africa. -

Adam Smith and the Austrian School of Economics: the Problem of Diamonds and Water

Stefan Poier 1st year Part-time Doctoral Studies Adam Smith and the Austrian School of Economics: The Problem of Diamonds and Water Keywords: Adam Smith, Austrian School of Economics, Value Paradox, Marginal Utility, Decision Making Introduction When end of 2017 Leonardo da Vinci's painting "Salvator Mundi" was auctioned off for over $450 million, it was nearly three times as expensive as the second most expensive painting, a Picasso, and it could have compensated for the state deficit of Lithuania. An absurdly high sum for a piece of wood and oil paint. How do you explain such a price? Neither the amount of time spent working on it, nor the benefits from this work alone could justify it. Why do we often pay high prices for goods with little use, but low prices for things that are sometimes partially vital? Generations of economists and philosophers have tried to resolve this apparent paradox. An explanation for this price is - quite simply - an individual’s willingness to pay this price. The prestige gain of owning one of only fifteen paintings of the probably most important artist and universal scholar of all time can already provide an enormous increase in status. It is the scarcity, the uniqueness of the artwork, which justified the high increase in utility or satisfaction. If there were any number of similar works, no one would pay more than the utility value for it. This – today rational – economic inference was not always granted. It is based on the recognition that the benefits of consumption of a good decreases with the amount consumed (and thus with the saturation of the consumer). -

International Literary Program

PROGRAM & GUIDE International Literary Program LISBON June 29 July 11 2014 ORGANIZATION SPONSORS SUPPORT GRÉMIO LITERÁRIO Bem-Vindo and Welcome to the fourth annual DISQUIET International Literary Program! We’re thrilled you’re joining us this summer and eagerly await meeting you in the inimitable city of Lisbon – known locally as Lisboa. As you’ll soon see, Lisboa is a city of tremendous vitality and energy, full of stunning, surprising vistas and labyrinthine cobblestone streets. You wander the city much like you wander the unexpected narrative pathways in Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, the program’s namesake. In other words, the city itself is not unlike its greatest writer’s most beguiling text. Thanks to our many partners and sponsors, traveling to Lisbon as part of the DISQUIET program gives participants unique access to Lisboa’s cultural life: from private talks on the history of Fado (aka The Portuguese Blues) in the Fado museum to numerous opportunities to meet with both the leading and up-and- coming Portuguese authors. The year’s program is shaping up to be one of our best yet. Among many other offerings we’ll host a Playwriting workshop for the first time; we have a special panel dedicated to the Three Marias, the celebrated trio of women who collaborated on one of the most subversive books in Portuguese history; and we welcome National Book Award-winner Denis Johnson as this year’s guest writer. Our hope is it all adds up to a singular experience that elevates your writing and affects you in profound and meaningful ways. -

Schools of Economic Thought (Pdf)

SCHOOLS OF ECONOMIC THOUGHT A BRIEF HISTORY OF ECONOMICS This isn't really essential to know, but may satisfy the curiosity of many. Mercantilism Economics is said to begin with Adam Smith in 1776. Prior to that, nobody thought of economics, or markets, as an object of study. It is not that they didn't pay attention to economic matters, it is simply that they didn't think of it in any systematic or coherent manner. It was all just off-the-cuff intuition and policy proposals by a myriad of merchants, government officials & journalists, principally in Britain. It is common to denote the period before 1776 as "Mercantilism". It wasn't a coherent school of thought, but a hodge-podge of varying ideas about improving tax revenues, the value & movements of gold and how nations competed for international commerce & colonies. Mostly protectionist, 'war-minded', and all haphazardly argued. (the principal features of the Mercantilist school are discussed in our "Gains from Trade" handout). There was some opposition to Mercantilist doctrines, notably among French and Scottish thinkers (e.g. Pierre de Boisguilbert, Francois Quesnay, Jacques Turgot and David Hume) Classical School The Enlightenment era (mid-1700s) in Europe brought a new spirit of scientific inquiry. Thinkers began looking to apply scientific principles not only to the physical world, but also to human society. In the same spirit that Sir Isaac Newton 'discovered' the "law of gravity" to explain the interaction of natural forces and decipher how the physical world operates, Enlightenment thinkers began trying to discover the "laws" of human interaction, to explain how human society operates. -

Austrian Economic Thought: Its Evolution and Its Contribution to Consumer Behavior

A Great Revolution in Economics –Vienna 1871 and after Austrian economic thought: its evolution and its contribution to consumer behavior Lazaros Th. Houmanidis Auke R. Leen A great REVOLUTION In economics —VIENNA 1871 and after AUSTRIAN ECONOMIC THOUGHT: ITS EVOLUTION AND ITS CONTRIBUTION TO CONSUMER BEHAVIOR Lazaros Th. Houmanidis Auke R. Leen The letter type on the cover is of Arnold Böcklin (Basel 1827-1901 Fiesole). It is a typical example of the Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) style—the fashionable style of art in Vienna at the end of the 19th century (the time older Austrianism came in full swing). In a sense, Böcklin’s work represents the essence of Austrianism: “Never was he interested in the accidental; he wanted the everlasting”. Cereales Foundation, publisher Wageningen University P.O. Box 357, 6700 AJ Wageningen, The Netherlands E [email protected] Printed by Grafisch Service Centrum Van Gils B.V. Cover design by Hans Weggen (Art Director Cereales) © 2001 Lazaros Th. Houmanidis and Auke R. Leen ISBN 90-805724-3-8 In the memory of our beloved colleague JACOB JAN KRABBE PREFACE A Great Revolution in Economics—Vienna 1871 and after is about the revolution in economic thought that started in Vienna in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. After a time of trying to save the objective value theory the time was there for a new awakening of economic thought. In Vienna, for the first time by the 1871 publication of Menger’s Grundsätze, value become subjective, and the market a process with a sovereign consumer. This book is about this awakening that proved to be more than a plaisanterie viennoise. -

Regarding the Past

Regarding the Past Proceedings of the 20th Conference of the History of Economic Thought Society of Australia University of Queensland 11-13 July 2007 Edited by Peter E. Earl and Bruce Littleboy This book comprises complete texts and/or abstracts of refereed papers presented at the 20th Conference of the History of Economic Thought Society of Australia held at The Women’s College, University of Queensland, 11-13 July 2007. © Selection and editorial material Peter E. Earl and Bruce Littleboy; individual chapters, the respective contributors Published by The School of Economics University of Queensland St Lucia, Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia ISBN: 9781 8649 98 979 (pbk); 9781 8649 98 955 (CD-ROM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed in Australia by the University of Queensland Printery Contents List of Contributors v Introduction Peter E. Earl and Bruce Littleboy vii 1 History for Economics: Learning from the Past 1 Alexander Dow and Sheila Dow 2 Theories of Economic Development in the Scottish Enlightenment 9 Alexander Dow and Sheila Dow 3 Ethical Foundations of Adam Smith’s Political Economy 25 James E. Alvey 4 Smith and the Materialist Theory of History 44 Jeremy Shearmur 5 Post-Keynesianism and the Possibility of a Post-Keynesian Politics 62 Geoff Dow 6 George Stigler’s Rhetoric – Dreams of Martin Luther 78 Craig Freedman 7 Why is the Austrian School’s Methodology Problematical? 103 Troy P.