Gender Transformations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mundial.Com Navegantecultural

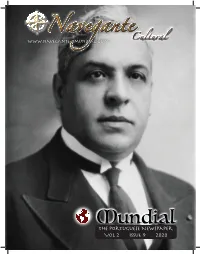

This is your outside front cover (OFC). The red line is the bleed area. www.navegante-omundial.com NaveganteCultural MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Vol 2 Issue 9 2020 This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. Letter from the Editor MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Aristides de Sousa One of those measures was the right of refusal Mendes saved the for consular officials to grant or issue Visas, set PUBLISHER / EDITORA lives of thousands first in Circular Number 10, and reinforced a Navegante Cultural Navigator of Jews fleeing the year later by Circular Number 14 in 1939. 204.981.3019 Nazis during his tenure as Portuguese At the same time, in reaction to the Consul in Bordeaux, Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany, in early EDITOR-IN-CHIEF France. -

Democratic Transition in Portugal and Spain: a Comparative View Autor(Es)

Democratic transition in Portugal and Spain: a comparative view Autor(es): Medina, João Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41962 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_17_18 Accessed : 29-Sep-2021 08:02:23 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt JOÃO MEDINA5 Revista de Historia das Ideias Vol. 17 (1995) DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION IN PORTUGAL AND SPAIN: A COMPARATIVE VIEW "Comme la vie est lente Et comme Vespérance violente" (Hozo slow life is And how violent is Hope) Apollinaire In 1976, two years after the beginning of the Portuguese revolu tion, which brought to an end the longest autocracy in European con temporary history, an American historian by the name of Robert Harvey, who had previously written that Portugal, a country even smaller than Scotland, "is a peanut of a country", raised what seemed to him the essential question concerning the then-uncertain process of democratic rebirth in the southwestern corner of Europe. -

Artigo 1 Para Ophiussa 1

OPHIUSSA OPHIUSSA Revista do Instituto de Arqueologia da Faculdade de Letras de Lisboa Nº 1, 1996 Direcção: Victor S. Gonçalves ([email protected]) Secretário: Carlos Fabião ([email protected]) Conselho de Redacção: Amilcar Guerra Ana Margarida Arruda Carlos Fabião João Carlos Senna-Martínez João Pedro Ribeiro João Zilhão Capa: Artlandia Endereço para correspondência e intercâmbio: Instituto de Arqueologia. Faculdade de Letras. P-1600-214. LISBOA. PORTUGAL As opiniões expressas não são necessariamente assumidas pelo colectivo que assume a gestão da Revista, sendo da responsabilidade exclusiva dos seus subscritores. Nota da direcção: Devido a circunstâncias de ordem vária, que seria desinteressante enumerar, tão diversas elas são, este número foi preparado para sair em 1995, mas só agora é publicado. Alguns textos foram muito ligeiramente revistos, mas o essencial, incluindo o texto de apresentação, refere-se àquela data, pelo que tem de ser contextualmente entendido. A periodicidade futura de esta publicação será bienal, sendo o próximo número datado de 2002, com textos entregues até Dezembro de 2001. No sentido de datar propostas científicas e de situar opiniões expressas, solicitou- se a todos os autores que indicassem nas suas contribuições a data de entrega dos originais, e, sempre que necessário, após o texto, a data de revisão última. A partir do nº 2, inclusive, as normas de publicação são idênticas às adoptadas pelo Instituto Português de Arqueologia, na sua Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia (http://www.ipa.min-cultura.pt). Dezembro de 2000 ÍNDICE ALGUMAS HISTÓRIAS EXEMPLARES (E OUTRAS MENOS) Victor S. Gonçalves ............................................................................................................................................. 5 A ARQUEOLOGIA PÓS-PROCESSUAL OU O PASSADO PÓS-MODERNO Mariana Diniz ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Country Profile Highlights Strategy

Country Profile Highlights Strategy Legal Framework inside Actors Infrastructure Services for Citizens Services for Businesses What’s eGovernment in Portugal ISA² Visit the e-Government factsheets online on Joinup.eu Joinup is a collaborative platform set up by the European Commission as part of the ISA² programme. ISA² supports the modernisation of the Public Administrations in Europe. Joinup is freely accessible. It provides an observatory on interoperability and e-Government and associated domains like semantic, open source and much more. Moreover, the platform facilitates discussions between public administrations and experts. It also works as a catalogue, where users can easily find and download already developed solutions. The main services are: Have all information you need at your finger tips; Share information and learn; Find, choose and re-use; Enter in discussion. This document is meant to present an overview of the eGoverment status in this country and not to be exhaustive in its references and analysis. Even though every possible care has been taken by the authors to refer to and use valid data from authentic sources, the European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the included information, nor does it accept any responsibility for any use thereof. Cover picture © AdobeStock Content © European Commission © European Union, 2018 Reuse is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. eGovernment in Portugal May 2018 Country Profile ......................................................................................................... -

Arqueólogos Portugueses Lisboa, 2017

2017 – Estado da Questão Coordenação editorial: José Morais Arnaud, Andrea Martins Design gráfico: Flatland Design Produção: Greca – Artes Gráficas, Lda. Tiragem: 500 exemplares Depósito Legal: 433460/17 ISBN: 978-972-9451-71-3 Associação dos Arqueólogos Portugueses Lisboa, 2017 O conteúdo dos artigos é da inteira responsabilidade dos autores. Sendo assim a As sociação dos Arqueólogos Portugueses declina qualquer responsabilidade por eventuais equívocos ou questões de ordem ética e legal. Desenho de capa: Levantamento topográfico de Vila Nova de São Pedro (J. M. Arnaud e J. L. Gonçalves, 1990). O desenho foi retirado do artigo 48 (p. 591). Patrocinador oficial arqueólogos portugueses Jacinta Bugalhão1 RESUMO Em Portugal, nas últimas décadas, o grupo profissional dos arqueólogos tem vivido um extraordinário aumen- to de dimensão, bem como diversas alterações no que se refere à sua estrutura, constituição e balanço social. Estas mudanças relacionam-se de perto com a evolução sociológica portuguesa e com o caminho do país rumo ao desenvolvimento e à vanguarda civilizacional. Neste artigo será abordada a evolução do grupo de pessoas que em Portugal se dedicam à prática da actividade arqueológica, durante todo o século XX e até à actualidade. Quantos são, quem são, qual a sua formação aca- démica, distribuição etária e de género, origem geográfica e forma de exercício da actividade (do amadorismo à profissionalização) serão alguns dos aspectos abordados. Palavras-chave: Arqueólogos, Arqueologia profissional, História da Arqueologia. ABSTRACT In Portugal, in the last decades, the professional group of archaeologists has experienced an extraordinary in- crease in size, as well as several changes regarding its structure, constitution and social balance. -

Portuguese Emigration Under the Corporatist Regime

From Closed to Open Doors: Portuguese Emigration under the Corporatist Regime Maria Ioannis B. Baganha University of Coimbra [email protected] Abstract This paper analyses the Portuguese emigration policy under the corporatist regime. It departs from the assumption that sending countries are no more than by bystanders in the migratory process. The paper goes a step further, claiming that in the Portuguese case, not only did the Estado Novo (New State) control the migratory flows that were occurring, but that it used emigration to its own advantage. I tried next to present evidence to show that by the analysis of the individual characteristics of the migrants and of their skills, their exodus couldn’t have harmed the country’s economic growth during the sixties, since the percentage of scientific and technical manpower was, when compared to other European countries, far too scarce to frame an industrial labour force higher than the existing one. The paper concludes that during this period, the most likely hypothesis is that the Portuguese migratory flow was composed of migrants that were redundant to the domestic economy. Keywords: Emigration, Portugal, Estado Novo, New State, Corporatist, Salazar, Migration Policy, Labour, Economy, Economic Growth Introduction The political sanctioning of immigration may foster open-door policies in order to maximise the country’s labour supply, it may induce the adoption of quota systems in order to help preserve cultural and political integrity, or it may even promote the incorporation of special skills and intellectual capital. In turn, the political sanctioning of emigration may lead to the selection, promotion, or restriction of emigrants’ departures, which can and usually does distort the composition of the migratory flow, directly affecting the level of remittances that emigration produces and thus its impact on the sending country’s economy. -

Human Rights and Constitution Making Human Rights and Constitution Making

HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING New York and Geneva, 2018 II HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications, 300 East 42nd St, New York, NY 10017, United States of America. E-mail: [email protected]; website: un.org/publications United Nations publication issued by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Photo credit: © Ververidis Vasilis / Shutterstock.com The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a figure indicates a reference to a United Nations document. HR/PUB/17/5 © 2018 United Nations All worldwide rights reserved Sales no.: E.17.XIV.4 ISBN: 978-92-1-154221-9 eISBN: 978-92-1-362251-3 CONTENTS III CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 I. CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS AND HUMAN RIGHTS ......................... 2 A. Why a rights-based approach to constitutional reform? .................... 3 1. Framing the issue .......................................................................3 2. The constitutional State ................................................................6 3. Functions of the constitution in the contemporary world ...................7 4. The constitution and democratic governance ..................................8 5. -

Contradictions of the Estado Novo in the Modernisation of Portugal: Design and Designers in the 1940'S and 50'S

“Design Policies: Between Dictatorship and Resistance” | December 2015 Edition CONTRADICTIONS OF THE ESTADO NOVO IN THE MODERNISATION OF PORTUGAL: DESIGN AND DESIGNERS IN THE 1940'S AND 50'S Helena Barbosa, Universidade de Aveiro ABSTRACT The period of Portuguese history known as the Estado Novo (1933-1974) presents a series of contradictions as regards the directives issued, possibly resulting from a lack of political cohesion. Considering the dichotomy between modernization and tradition that existed between the 1940s and ‘50s, and the obvious validity of the government’s actions, this paper aims to demonstrate the contradictory attitudes towards the modernization of the country via different routes, highlighting the role of ‘designers’ as silent interlocutors and agents of change in this process. Various documents are analysed, some published under the auspices of the Estado Novo, others in the public sphere, in order to reveal the various partnerships that were in operation and the contrasting attitudes towards the government at the time. Other activities taking place in the period are also analysed, both those arising from state initiatives and others that were antithetical to it. The paper reveals the need to break with the political power in order to promote artistic and cultural interests, and describes initiatives designed to promote industry in the country, some launched by the Estado Novo, others by companies. It focuses upon the teaching of art, which later gave rise to the teaching of design, and on the presence of other institutions and organizations that contributed to the modernization of Portugal, in some cases by mounting exhibitions in Portugal and abroad, as well as other artistic activities such as graphic design, product design and interior decoration, referring to the respective designers, artefacts and spaces. -

Brochura HCP V10.3

PORTUGAL A PRIVILEGED DESTINATION FOR MEDICAL TOURISM Contents - Manuel Caldeira Cabral – Minister of Economy - Adalberto Campos Fernandes – Minister of Health - Salvador de Mello - President of Health Cluster Portugal - Portugal - A Privileged Destination - Healthcare in Portugal - Areas of excellence in Portuguese Healthcare - Cardiology & Cardiac Surgery - Orthopedics - Rehabilitation - Oncology - Plastic Surgery - Obesity - Ophthalmology - OB/GYN - Assisted Reproductive Technology - Check-ups - Portugal facts and figures - How to get in touch or find out more MEDICAL TOURISM IN PORTUGAL Terminal de Cruzeiros do Porto de Leixões Manuel Caldeira Cabral Minister of Economy In the past few years, Portugal has established itself as one of the best touristic destinations all across the world. The growth of this sector in our country has been a major Key for the wealth creation in Portugal, and one of the main drivers for our economy. Last year, 2017, we broke new records again – revenue increased 20%, something we had not seen in the last two decades. So strong is the performance of tourism in Portugal that it accounts for more than half the services exports and 18% of the exports of goods and services. Last year, overall, Portuguese exports Kept growing and represented 42,5% of our GDP, a new record, which clearly shows how sustainable and resilient the Portuguese economy is. We are also aware that the demand for high quality health treatments is growing, namely because of demographics, and we have identified that as a priority in our National Strategy for Tourism 2027. We have some of the best qualified doctors and nurses and modern and functional medical infrastructures that are able to serve both locals and tourists. -

Portugal's History Since 1974

Portugal’s history since 1974 Stewart Lloyd-Jones ISCTE-Lisbon AN IMPERIAL LEGACY The Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos) that broke out on the morning of 25 April 1974 has had a profound effect on Portuguese society, one that still has its echoes today, almost 30 years later, and which colours many of the political decision that have been, and which continue to be made. During the authoritarian regime of António de Oliveira Salazar (1932-68) and his successor, Marcello Caetano (1968-74), Portugal had existed in a world of its own construction. Its vast African empire (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé e Príncipe, and Cape Verde) was consistently used to define Portugal’s self-perceived identity as being ‘in, but not of Europe’. Within Lisbon’s corridors of power, the dissolution of the other European empires was viewed with horror, and despite international opprobrium and increasing isolation, the Portuguese dictatorship was in no way prepared to follow the path of decolonisation. As Salazar was to defiantly declare, Portugal would stand ‘proudly alone’, indeed, for a regime that had consciously legitimated itself by ‘turning its back on Europe’, there could be no alternative course of action. Throughout the 1960s and early-1970s, the Portuguese people were to pay a high price for the regime’s determination to remain in Africa. From 1961 onwards, while the world’s attention was focused on events in south-east Asia, Portugal was fighting its own wars. By the end of the decade, the Portuguese government was spending almost half of its GNP on sustaining a military presence of over 150,000 troops in Africa. -

Regulando a Guerra Justa E O Imperialismo Civilizatório

José Pina Delgado REGULANDO A GUERRA JUSTA E O IMPERIALISMO CIVILIZATÓRIO UM ESTUDO HISTÓRICO E JURÍDICO SOBRE OS DESAFIOS COLOCADOS AO DIREITO INTERNACIONAL E AO DIREITO CONSTITUCIONAL PELAS INTERVENÇÕES HUMANITÁRIAS (UNILATERAIS) Tese com vista à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Direito na especialidade de Direito Público Fevereiro de 2016 DECLARAÇÃO ANTIPLÁGIO Declaro que o texto apresentado é de minha autoria exclusiva e que toda a utilização de contribuições e texto alheios está devidamente referenciada. i DEDICATÓRIA Dedicado a Manuel Jesus do Nascimento Delgado, in memoriam ii AGRADECIMENTOS Para conceber e executar um projeto necessariamente exigente foi necessário contar com conversas frequentes com o Professor Catedrático Jorge Bacelar Gouveia, especialista em Direito Público, a quem dirijo os meus agradecimentos por todo o apoio prestado na sua concretização. Da mesma área temática, é de justiça ressaltar o papel desempenhado pelo Professor Nuno Piçarra, que tudo fez para que pudesse submeter esta tese na Nova Direito e a quem devo várias das recomendações de forma, de textura e de apresentação da mesma. Os notáveis jushistoriadores Cristina Nogueira da Silva e Pedro Barbas Homem, que me concederam o privilégio de discutir a metodologia usada na tese e transmitiram sugestões importantes, que somente a insistência me impediram de seguir integralmente, deixam-me igualmente obrigado. Registo igualmente o incentivo e intermediação feitas pelos Professores Rui Moura Ramos e Vital Moreira da Universidade de Coimbra, e Dário Moura Vicente da Faculdade de Direito de Lisboa, para a apresentação de partes da tese, acesso a bibliotecas e contatos com docentes, bem como a chamada de atenção do Professor José Melo Alexandrino sobre a importância do princípio da solidariedade para todas as áreas do Direito Público. -

Portugal, O Estado Novo, António De Oliveira Salazar

PORTUGAL, O ESTADO NOVO, ANTÓNIO DE OLIVEIRA SALAZAR E A ONU: POSICIONAMENTO(S) E (I)LEGALIDADES NO PÓS II GUERRA MUNDIAL (1945-1970) Ana Campina e Sérgio Tenreiro Tomás Resumo: A análise do discurso e da retórica de António de Oliveira Salazar, e do Estado Novo, as Relações Internacionais e Diplomáticas portuguesas são reveladoras da disparidade entre a imagem criada pelo discurso e pela realidade. Portugal, pelo seu posicionamento geopolítico, desempenhou um importante papel durante a II Guerra Mundial pela Neutralidade Colaborante, com os Aliados e com Hitler. As Relações Internacionais com a ONU, como com outras Organizações, foram diplomáticas mas complexas pelo Império Colonial. Salazar não contestou nem se sentiu obrigado a implementar as medidas solicitadas. Com a Guerra Colonial Portugal recebeu diversas “chamadas de atenção”, em particular pela ONU, que ignorou e em nada mudando a luta armada, com resultados catastróficos para todos e com a morte de milhares de militares, assim como com consequências físicas e psicológicas para os sobreviventes. Indubitavelmente Salazar gerou uma imagem díspar da realidade na qual se violavam os Direitos Fundamentais e Humanos. Palavras-Chave: Salazar, Estado Novo, Discurso, ONU Title: Portugal, Estado Novo, António de Oliveira Salazar and the UN: Position(s) and (i)legalities in the post World War II (1945-1970) Abstract: The analysis of António de Oliveira Salazar and the Estado Novo speech and rhetoric, the Portuguese International Relations and the Diplomacy are clear concerning the “distance” between the image created by th e speech and the reality. Portugal, by his geopolitical position, had an important role during the II World War by the Cooperating Neutrality, with the Allies and with Hitler.