Portugal's History Since 1974

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mundial.Com Navegantecultural

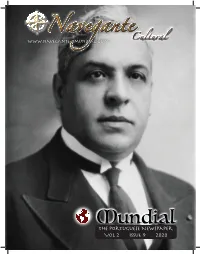

This is your outside front cover (OFC). The red line is the bleed area. www.navegante-omundial.com NaveganteCultural MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Vol 2 Issue 9 2020 This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. Letter from the Editor MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Aristides de Sousa One of those measures was the right of refusal Mendes saved the for consular officials to grant or issue Visas, set PUBLISHER / EDITORA lives of thousands first in Circular Number 10, and reinforced a Navegante Cultural Navigator of Jews fleeing the year later by Circular Number 14 in 1939. 204.981.3019 Nazis during his tenure as Portuguese At the same time, in reaction to the Consul in Bordeaux, Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany, in early EDITOR-IN-CHIEF France. -

Revolution and Democracy: Sociopolitical Systems in the Context of Modernisation Leonid E

preview version Revolution and Democracy: Sociopolitical Systems in the Context of Modernisation Leonid E. Grinin and Andrey V. Korotayev Abstract The stability of socio-political systems and the risks of destabi- lisation in the process of political transformation are among the most im- portant issues of social development; the transition to democracy may pose a serious threat to the stability of a respective socio-political system. This article studies the issue of democratisation. It highlights the high economic and social costs of a rapid transition to democracy for countries unpre- pared for it—democracy resulting from revolutions or similar large-scale events. The authors believe that in a number of cases authoritarian regimes turn out to be more effective in economic and social terms than emerging democracies, especially those of a revolutionary type, which are often inca- pable of ensuring social order and may have a swing to authoritarianism. Effective authoritarian regimes can also be a suitable form of transition to an efficient and stable democracy. Using historical and contemporary examples, particularly the recent events in Egypt, the article investigates various correlations between revolutionary events and the possibility of es- tablishing democracy in a society. Keywords: democracy, revolution, extremists, counterrevolution, Isla- mists, authoritarianism, military takeover, economic efficiency, globali- sation, Egypt Introduction It is not surprising that in five years none of the revolutions of the Arab Spring has solved any urgent issues. Unfortunately, this was probably never a possibility. Various studies suggest a link between 110 preview version revolutions and the degree of modernisation of a society.1 Our research reveals that the very processes of modernisation, regardless of the level of consumption and the rate of population growth, is closely and organically linked to the risk of social and political upheaval, which can Leonid E. -

Planting Power ... Formation in Portugal.Pdf

Promotoren: Dr. F. von Benda-Beckmann Hoogleraar in het recht, meer in het bijzonder het agrarisch recht van de niet-westerse gebieden. Ir. A. van Maaren Emeritus hoogleraar in de boshuishoudkunde. Preface The history of Portugal is, like that of many other countries in Europe, one of deforestation and reafforestation. Until the eighteenth century, the reclamation of land for agriculture, the expansion of animal husbandry (often on communal grazing grounds or baldios), and the increased demand for wood and timber resulted in the gradual disappearance of forests and woodlands. This tendency was reversed only in the nineteenth century, when planting of trees became a scientifically guided and often government-sponsored activity. The reversal was due, on the one hand, to the increased economic value of timber (the market's "invisible hand" raised timber prices and made forest plantation economically attractive), and to the realization that deforestation had severe impacts on the environment. It was no accident that the idea of sustainability, so much in vogue today, was developed by early-nineteenth-century foresters. Such is the common perspective on forestry history in Europe and Portugal. Within this perspective, social phenomena are translated into abstract notions like agricultural expansion, the invisible hand of the market, and the public interest in sustainably-used natural environments. In such accounts, trees can become gifts from the gods to shelter, feed and warm the mortals (for an example, see: O Vilarealense, (Vila Real), 12 January 1961). However, a closer look makes it clear that such a detached account misses one key aspect: forests serve not only public, but also particular interests, and these particular interests correspond to specific social groups. -

O Marcelismo, O Movimento Dos Capitães E O

LUÍS PEDRO MELO DE CARVALHO . O MOVIMENTO DOS CAPITÃES, O MFA E O 25 DE ABRIL: DO MARCELISMO À QUEDA DO ESTADO NOVO Dissertação apresentada para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Ciência Política: Cidadania e Governação no Curso de Mestrado em Ciência Política: Cidadania e Governação, conferido pela Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias. Orientador: Professor Doutor José Filipe Pinto Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Lisboa 2009 Luís Pedro Melo de Carvalho O Movimento dos Capitães, o MFA e o 25 de Abril: do marcelismo à queda do Estado Novo Epígrafe É saber antigo que um regime forte, apoiado nas Forças Armadas, não pode ser derrubado senão na sequela de uma guerra perdida que destrua o exército, ou por revolta do exército. Adriano Moreira (1985, p. 37) Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas 2 Luís Pedro Melo de Carvalho O Movimento dos Capitães, o MFA e o 25 de Abril: do marcelismo à queda do Estado Novo Dedicatória Ao meu querido Pai, com saudade. À minha Mulher, emoção tranquila da minha vida. Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas 3 Luís Pedro Melo de Carvalho O Movimento dos Capitães, o MFA e o 25 de Abril: do marcelismo à queda do Estado Novo Agradecimentos Ao Professor Doutor José Filipe Pinto, que tive o prazer de conhecer durante este Mestrado, pelo seu profissionalismo e forma empenhada como dirige as aulas e as orientações e que muito contribuiu para o sucesso daqueles que por si são orientados. -

A Estratégia De Informação De Marcello Caetano O Último

A estratégia de informação de Marcello Caetano o último governante do Estado Novo The information strategy of Marcello Caetano, the last ruler of Estado Novo La estrategia de información de Marcello Caetano el último gobernante del Estado Nuevo https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_35_15 Ana Cabrera Instituto de História Contemporânea Resumo Este artigo analisa a estratégia de informação levada a cabo por Marcello Caetano quando, em setembro de 1968, substituiu Salazar na presidência do Conselho de Ministros. Esta estratégia consistiu na realização de acontecimen- tos que lhe assegurassem uma boa visibilidade na imprensa, afirmação de uma relação mais próxima com os jornalistas, e realização das conversas em famí- lia teledifundidas. A investigação assenta no estudo do perfil político de Marcello Caetano suporta- da por fontes (cartas, textos, livros e entrevistas) e na análise de jornais da época (A Capital, Diário de Lisboa, Diário Popular, Diário de Notícias) no período compreendi- do entre setembro de 1968 e setembro de 1969. Como conclusão assinala-se que a construção da imagem deste político na imprensa favoreceu o início da sua gover- nação através da construção de uma personalidade política, social e familiar bem distinta da de Salazar. Palavras-chave Marcello Caetano; estratégia de informação; imprensa; Estado Novo; censura Abstract This paper examines the information strategy followed by Marcello Caetano since September 1968, when he succeeded Salazar in the president of Council of Ministers. This strategy implied setting up events capable of ensuring him a good visibility on the media, establishing a closer relationship with journalists, and broadcasting his own TV programme “conversations in family”. -

Democracy As an Effort Rayna Gavrilova, CEE Trust USAID/Bulgaria Closing Ceremony October 10, 2007, Sofia

Democracy as an Effort Rayna Gavrilova, CEE Trust USAID/Bulgaria Closing Ceremony October 10, 2007, Sofia Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, When I was invited to say a few words at the official closing of the United States Agency for International Development in Bulgaria, the first title that came to my mind was “Democracy as an Effort.” When change began, democracy for us was mostly about revolution – from Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, to Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, to Ukraine’s Orange Revolution. Eighteen years later, we already realize that democracy is most of all a constant effort made by citizens and institutions. The post- communist countries, including Bulgaria, were lucky not to have been left alone in this process. The international assistance for laying the foundations of liberal democracy and market economy came early and was timely. The United States was among the first countries to get involved. American public organizations such as USAID, non- governmental organizations and an impressive number of individuals made a long-lasting and systematic effort to elucidate and support this social order which, without doubt, remains the choice of the larger part of humanity. USAID left visible traces in Bulgarian social life. Today we hardly remember it, but through their programs a whole variety of previously unknown concepts, such as “rule of law,” “local government initiative,” “transparency”, and “entrepreneurship promotion” entered the Bulgarian vocabulary and practice, and are today the foundation of the state. Some of the terms which had no equivalent in the rigid vocabulary of socialism remain untranslated even today: probation, mediation, microcredit. -

The 'Colorful' Revolution of Kyrgyzstan: Democratic Transition

The ‘Colorful’ Revolution of Kyrgyzstan: Democratic Transition or Global Competition? Yilmaz Bingol* This paper aims to analyze the reasons behind the recent revolution of Kyrgyzstan. I will argue that explaining the revolution through just the rhetoric of “democracy and freedom” needs to be reassessed, as comparing with its geo-cultural environment; Kyrgyzstan had been the most democratic of Central Asian republics. Thus, the paper argues that global competition between US and China-Russia should seriously be taken under consideration as a landmark reason behind the Kyrgyz revolution. The “Rose Revolution” in Georgia and the “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine followed by yet another “colorful” revolution in Kyrgyzstan in the March of 2005. A group of opposition who were dissatisfied with the result of the Parliamentary Election taken place on February 27th and March 13th of 2005 upraised against incumbent regime of Askar Akayev. Accusing the incumbent regime with the felony and asking for more democracy and freedom, the opposition took over Akayev from the power and closed the last stage of the colorful revolution of Kyrgyzstan on March 24-25, 2005. Common characteristics of all these colorful revolutionist were that they all used rhetoric of “democracy and freedom,” and that they were all pro-western especially pro-American. It seems that it has become a tradition in the West to call such revolutions with the colorful names. This tradition may trace back to Samuel Huntington’s famous “third wave democracy” which was started with “Carnation Revolution” of Portugal in 1974. As Western politicians and academicians have often used such “colorful” names for post-communist and post-Soviet cases since then, they must have regarded these revolutions as the extension of what Huntington has called the “third wave”. -

Marcello Caetano: O Ethos Intelectual E As Artimanhas Do Poder1

rev. hist. (São Paulo), n. 177, r00518, 2018 Lincoln Secco http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9141.rh.2018.144016 Marcello Caetano: o ethos intelectual e as artimanhas do poder RESENHA MARCELLO CAETANO: O ETHOS INTELECTUAL E AS ARTIMANHAS DO PODER1 Lincoln Secco2 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo – São Paulo – Brasil Resenha do livro: MARTINHO, Francisco Carlos Palomanes. Marcello Caetano: Uma biografia (1906-1980). Lisboa: Objectiva, 2016. Portugal sobreviveu na periferia europeia às forças mais poderosas que sacudiram o século XX: as guerras mundiais, as ditaduras e a descoloniza- ção. A narrativa desses processos já seria um desafio imponente. Mais difícil, porém, é filtrá-los pelas lentes de uma vida singular, ainda que a de um homem que viria a desempenhar papel de relevo na política de seu país. Em 600 páginas, com estilo límpido, o historiador Francisco Carlos Palo- manes Martinho compôs uma obra que já é referência. Dez capítulos impe- cavelmente equilibrados, com introdução explicativa e conclusões em cada um deles, e que findam amiúde com um convite à leitura do próximo capí- 1 Resenha do livro: MARTINHO, Francisco Carlos Palomanes. Marcello Caetano: Uma biografia (1906-1980). Lisboa: Objectiva, 2016. 2 Professor no Departamento de História da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo – FFLCH/USP. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 rev. hist. (São Paulo), n. 177, r00518, 2018 Lincoln Secco http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9141.rh.2018.144016 Marcello Caetano: o ethos intelectual e as artimanhas do poder tulo. Uma narrativa por vezes em suspense que não perde por isso nada do rigor acadêmico, provado na destreza com que coletou, selecionou e anali- sou suas fontes e ampla bibliografia, com destaque para a consulta da epis- tolografia, de notícias de jornais, manuscritos e outros documentos inéditos. -

Contradictions of the Estado Novo in the Modernisation of Portugal: Design and Designers in the 1940'S and 50'S

“Design Policies: Between Dictatorship and Resistance” | December 2015 Edition CONTRADICTIONS OF THE ESTADO NOVO IN THE MODERNISATION OF PORTUGAL: DESIGN AND DESIGNERS IN THE 1940'S AND 50'S Helena Barbosa, Universidade de Aveiro ABSTRACT The period of Portuguese history known as the Estado Novo (1933-1974) presents a series of contradictions as regards the directives issued, possibly resulting from a lack of political cohesion. Considering the dichotomy between modernization and tradition that existed between the 1940s and ‘50s, and the obvious validity of the government’s actions, this paper aims to demonstrate the contradictory attitudes towards the modernization of the country via different routes, highlighting the role of ‘designers’ as silent interlocutors and agents of change in this process. Various documents are analysed, some published under the auspices of the Estado Novo, others in the public sphere, in order to reveal the various partnerships that were in operation and the contrasting attitudes towards the government at the time. Other activities taking place in the period are also analysed, both those arising from state initiatives and others that were antithetical to it. The paper reveals the need to break with the political power in order to promote artistic and cultural interests, and describes initiatives designed to promote industry in the country, some launched by the Estado Novo, others by companies. It focuses upon the teaching of art, which later gave rise to the teaching of design, and on the presence of other institutions and organizations that contributed to the modernization of Portugal, in some cases by mounting exhibitions in Portugal and abroad, as well as other artistic activities such as graphic design, product design and interior decoration, referring to the respective designers, artefacts and spaces. -

Independence, Intervention, and Internationalism Angola and the International System, 1974–1975

Independence, Intervention, and Internationalism Angola and the International System, 1974–1975 ✣ Candace Sobers Mention the Cold War and thoughts instinctively turn to Moscow, Washing- ton, DC, and Beijing. Fewer scholars examine the significant Cold War strug- gles that took place in the African cities of Luanda, Kinshasa, and Pretoria. Yet in 1975 a protracted war of national liberation on the African continent escalated sharply into a major international crisis. Swept up in the momen- tum of the Cold War, the fate of the former Portuguese colony of Angola captured the attention of policymakers from the United States to Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), Colombia to Luxembourg. The struggle over Angolan independence from Portugal was many things: the culmination of sixteen years of intense anti-colonial struggle and the launch of 28 years of civil war, a threat to white minority rule in southern Africa, and another battle on the long road to ending empire and colonialism. It was also a strug- gle to define and create a viable postcolonial state and to carry out a radical transformation of the sociopolitical structure of Angolan society. Recent scholarship on Angolan independence has provided an impres- sive chronology of the complicated saga yet has less to say about the wider consequences and ramifications of a crisis that, though located in southern Africa, was international in scope. During the anti-colonial struggle, U.S. sup- port reinforced the Portuguese metropole, contiguous African states harbored competing revolutionaries, and great and medium powers—including Cuba, China, and South Africa—provided weapons, combat troops, and mercenar- ies to the three main national liberation movements. -

197 from Dictatorship to Democracy in Portugal

ISSN2039Ͳ2117MediterraneanJournalofSocialSciencesVol.3(6)March2012 From Dictatorship to Democracy in Portugal: The use of Communication as a Political Strategy Célia Maria Taborda da Silva Ph.D., Professor of Contemporary History Lusófona University of Porto, Portugal Email:[email protected] Abstract: Like in every Fascist Regime, with its wide range of limited freedom, in Portugal, the New State forbade the freedom of speech and started controlling the Media, by using them to promote the Regime. The political speeches by António de Oliveira Salazar with the old political ideas of “God”, Homeland” and “Family” of the authoritarian Regimes became state dogmas from the thirties of the 20th century on. As Salazar stated, “ Only what we know that exists truly exists”. According to this thought a great propaganda strategy of absolute certainties was created. The State even created a Secretariat for the National Propaganda which aimed to frame the social everyday life into the spirit of the Regime. From the forties on, due to international happenings there is a decrease of the ideological propaganda speech of the Government, since the main aim was the political survival. The fall of Dictatorship, in April 1974, made the freedom of speech possible. However there wasn’t a State impartiality regarding the Media. The revolution strategists immediately used the radio and the newspapers to spread news pro the political rebellion and the television to present themselves to the country. It is obvious that with the abolition of censorship there was a radical change in the system of political communication. But a long time of Democracy was necessary for the Media not to suffer political and governmental pressure. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83720-0 - The Cambridge History of the Cold War: Crises and Détente: Volume II Edited by Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad Index More information Index Cumulative index for Volumes I, II, and III. Bold page numbers refer to maps and photographs. 9/11 attacks, III.134, 537, 550, 554–5 anti-Sovietism, I.150 Berlin crisis, II.168 abortion, III.468, 469, 473 Cuban missile crisis, II.73 Abstract Expressionism, II.30 division of Germany and, II.482–3 Accornero, Aris (Italian social scientist), I.54 European integration, II.182, 183–4 Achaeans, II.1 French relations, II.168, 169, 184 Acheson, Dean, I.78 German unification and, II.203 Acheson–Lilienthal Report, II.397 Khrushchev and, I.319 Excomm, II.71 loss of power, II.483 on Germany, II.119, III.156 Marshall Plan, I.170 grand strategy, I.84–6 NPT and, II.408 Ho Chi Minh and, I.82–3 nuclear weapons, II.487 Japanese policy, I.82, III.156 US relations, II.484 Korean War, I.276 values, II.462–3 Marshall Plan and, I.155, 159 Advanced Research Projects Agency, see NATO, I.81 ARPA Pacific policy, I.274 advertising, III.503, 504–5 political influence, I.83 Adzhubei, Aleksei (Soviet journalist), III.402 postwar assessment, I.74 affluent society, II.510–13, 518 on racial segregation, I.433–4, III.456 Afghanistan Schuman Plan and, II.182 Al Qaeda, III.133–4 Ackermann, Anton (German Communist), bibliography, III.566 I.180 Cold War and, I.484 Acton, John (British historian) I.1, 2 Egyptian relations, III.126 Adamec, Ladislav (Czechoslovak prime fundamentalism, III.536–7