Revolution in Bad Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion and Politics

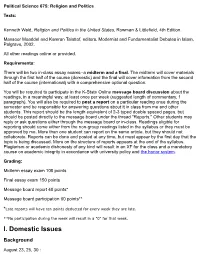

Political Science 675: Religion and Politics Texts: Kenneth Wald, Religion and Politics in the United States, Rowman & Littlefield, 4th Edition. Mansoor Moaddel and Kamran Talattof, editors, Modernist and Fundamentalist Debates in Islam, Palgrave, 2002. All other readings online or provided. Requirements: There will be two in-class essay exams--a midterm and a final. The midterm will cover materials through the first half of the course (domestic) and the final will cover information from the second half of the course (international) with a comprehensive optional question. You will be required to participate in the K-State Online message board discussion about the readings, in a meaningful way, at least once per week (suggested length of commentary, 1 paragraph). You will also be required to post a report on a particular reading once during the semester and be responsible for answering questions about it in class from me and other students. This report should be the length equivalent of 2-3 typed double spaced pages, but should be posted directly to the message board under the thread "Reports." Other students may reply or ask questions either through the message board or in-class. Readings eligible for reporting should come either from the non-group readings listed in the syllabus or they must be approved by me. More than one student can report on the same article, but they should not collaborate. Reports can be done and posted at any time, but must appear by the first day that the topic is being discussed. More on the structure of reports appears at the end of the syllabus. -

Revolution and Democracy: Sociopolitical Systems in the Context of Modernisation Leonid E

preview version Revolution and Democracy: Sociopolitical Systems in the Context of Modernisation Leonid E. Grinin and Andrey V. Korotayev Abstract The stability of socio-political systems and the risks of destabi- lisation in the process of political transformation are among the most im- portant issues of social development; the transition to democracy may pose a serious threat to the stability of a respective socio-political system. This article studies the issue of democratisation. It highlights the high economic and social costs of a rapid transition to democracy for countries unpre- pared for it—democracy resulting from revolutions or similar large-scale events. The authors believe that in a number of cases authoritarian regimes turn out to be more effective in economic and social terms than emerging democracies, especially those of a revolutionary type, which are often inca- pable of ensuring social order and may have a swing to authoritarianism. Effective authoritarian regimes can also be a suitable form of transition to an efficient and stable democracy. Using historical and contemporary examples, particularly the recent events in Egypt, the article investigates various correlations between revolutionary events and the possibility of es- tablishing democracy in a society. Keywords: democracy, revolution, extremists, counterrevolution, Isla- mists, authoritarianism, military takeover, economic efficiency, globali- sation, Egypt Introduction It is not surprising that in five years none of the revolutions of the Arab Spring has solved any urgent issues. Unfortunately, this was probably never a possibility. Various studies suggest a link between 110 preview version revolutions and the degree of modernisation of a society.1 Our research reveals that the very processes of modernisation, regardless of the level of consumption and the rate of population growth, is closely and organically linked to the risk of social and political upheaval, which can Leonid E. -

PROTESTS and REGIME SUPPRESSION in POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY n OCTOBER 2020 n PN85 PROTESTS AND REGIME SUPPRESSION IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Saeid Golkar Green Movement members tangle with Basij and police forces, 2009. he nationwide protests that engulfed Iran in late 2019 were ostensibly a response to a 50 percent gasoline price hike enacted by the administration of President Hassan Rouhani.1 But in little time, complaints Textended to a broader critique of the leadership. Moreover, beyond the specific reasons for the protests, they appeared to reveal a deeper reality about Iran, both before and since the 1979 emergence of the Islamic Republic: its character as an inherently “revolutionary country” and a “movement society.”2 Since its formation, the Islamic Republic has seen multiple cycles of protest and revolt, ranging from ethnic movements in the early 1980s to urban riots in the early 1990s, student unrest spanning 1999–2003, the Green Movement response to the 2009 election, and upheaval in December 2017–January 2018. The last of these instances, like the current round, began with a focus on economic dissatisfaction and then spread to broader issues. All these movements were put down by the regime with characteristic brutality. © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SAEID GOLKAR In tracking and comparing protest dynamics and market deregulation, currency devaluation, and the regime responses since 1979, this study reveals that cutting of subsidies. These policies, however, spurred unrest has become more significant in scale, as well massive inflation, greater inequality, and a spate of as more secularized and violent. -

Democracy As an Effort Rayna Gavrilova, CEE Trust USAID/Bulgaria Closing Ceremony October 10, 2007, Sofia

Democracy as an Effort Rayna Gavrilova, CEE Trust USAID/Bulgaria Closing Ceremony October 10, 2007, Sofia Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, When I was invited to say a few words at the official closing of the United States Agency for International Development in Bulgaria, the first title that came to my mind was “Democracy as an Effort.” When change began, democracy for us was mostly about revolution – from Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, to Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, to Ukraine’s Orange Revolution. Eighteen years later, we already realize that democracy is most of all a constant effort made by citizens and institutions. The post- communist countries, including Bulgaria, were lucky not to have been left alone in this process. The international assistance for laying the foundations of liberal democracy and market economy came early and was timely. The United States was among the first countries to get involved. American public organizations such as USAID, non- governmental organizations and an impressive number of individuals made a long-lasting and systematic effort to elucidate and support this social order which, without doubt, remains the choice of the larger part of humanity. USAID left visible traces in Bulgarian social life. Today we hardly remember it, but through their programs a whole variety of previously unknown concepts, such as “rule of law,” “local government initiative,” “transparency”, and “entrepreneurship promotion” entered the Bulgarian vocabulary and practice, and are today the foundation of the state. Some of the terms which had no equivalent in the rigid vocabulary of socialism remain untranslated even today: probation, mediation, microcredit. -

The 'Colorful' Revolution of Kyrgyzstan: Democratic Transition

The ‘Colorful’ Revolution of Kyrgyzstan: Democratic Transition or Global Competition? Yilmaz Bingol* This paper aims to analyze the reasons behind the recent revolution of Kyrgyzstan. I will argue that explaining the revolution through just the rhetoric of “democracy and freedom” needs to be reassessed, as comparing with its geo-cultural environment; Kyrgyzstan had been the most democratic of Central Asian republics. Thus, the paper argues that global competition between US and China-Russia should seriously be taken under consideration as a landmark reason behind the Kyrgyz revolution. The “Rose Revolution” in Georgia and the “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine followed by yet another “colorful” revolution in Kyrgyzstan in the March of 2005. A group of opposition who were dissatisfied with the result of the Parliamentary Election taken place on February 27th and March 13th of 2005 upraised against incumbent regime of Askar Akayev. Accusing the incumbent regime with the felony and asking for more democracy and freedom, the opposition took over Akayev from the power and closed the last stage of the colorful revolution of Kyrgyzstan on March 24-25, 2005. Common characteristics of all these colorful revolutionist were that they all used rhetoric of “democracy and freedom,” and that they were all pro-western especially pro-American. It seems that it has become a tradition in the West to call such revolutions with the colorful names. This tradition may trace back to Samuel Huntington’s famous “third wave democracy” which was started with “Carnation Revolution” of Portugal in 1974. As Western politicians and academicians have often used such “colorful” names for post-communist and post-Soviet cases since then, they must have regarded these revolutions as the extension of what Huntington has called the “third wave”. -

Independence, Intervention, and Internationalism Angola and the International System, 1974–1975

Independence, Intervention, and Internationalism Angola and the International System, 1974–1975 ✣ Candace Sobers Mention the Cold War and thoughts instinctively turn to Moscow, Washing- ton, DC, and Beijing. Fewer scholars examine the significant Cold War strug- gles that took place in the African cities of Luanda, Kinshasa, and Pretoria. Yet in 1975 a protracted war of national liberation on the African continent escalated sharply into a major international crisis. Swept up in the momen- tum of the Cold War, the fate of the former Portuguese colony of Angola captured the attention of policymakers from the United States to Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), Colombia to Luxembourg. The struggle over Angolan independence from Portugal was many things: the culmination of sixteen years of intense anti-colonial struggle and the launch of 28 years of civil war, a threat to white minority rule in southern Africa, and another battle on the long road to ending empire and colonialism. It was also a strug- gle to define and create a viable postcolonial state and to carry out a radical transformation of the sociopolitical structure of Angolan society. Recent scholarship on Angolan independence has provided an impres- sive chronology of the complicated saga yet has less to say about the wider consequences and ramifications of a crisis that, though located in southern Africa, was international in scope. During the anti-colonial struggle, U.S. sup- port reinforced the Portuguese metropole, contiguous African states harbored competing revolutionaries, and great and medium powers—including Cuba, China, and South Africa—provided weapons, combat troops, and mercenar- ies to the three main national liberation movements. -

The Iranian Revolution, Past, Present and Future

The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Dr. Zayar Copyright © Iran Chamber Society The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Content: Chapter 1 - The Historical Background Chapter 2 - Notes on the History of Iran Chapter 3 - The Communist Party of Iran Chapter 4 - The February Revolution of 1979 Chapter 5 - The Basis of Islamic Fundamentalism Chapter 6 - The Economics of Counter-revolution Chapter 7 - Iranian Perspectives Copyright © Iran Chamber Society 2 The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Chapter 1 The Historical Background Iran is one of the world’s oldest countries. Its history dates back almost 5000 years. It is situated at a strategic juncture in the Middle East region of South West Asia. Evidence of man’s presence as far back as the Lower Palaeolithic period on the Iranian plateau has been found in the Kerman Shah Valley. And time and again in the course of this long history, Iran has found itself invaded and occupied by foreign powers. Some reference to Iranian history is therefore indispensable for a proper understanding of its subsequent development. The first major civilisation in what is now Iran was that of the Elamites, who might have settled in South Western Iran as early as 3000 B.C. In 1500 B.C. Aryan tribes began migrating to Iran from the Volga River north of the Caspian Sea and from Central Asia. Eventually two major tribes of Aryans, the Persian and Medes, settled in Iran. One group settled in the North West and founded the kingdom of Media. The other group lived in South Iran in an area that the Greeks later called Persis—from which the name Persia is derived. -

Ideology and the Iranian Revolution1

Ideology and the Iranian Revolution1 Mehdi Shadmehr2 First Draft: May 2008. This Draft: Summer 2011 Comments are welcomed. 1I wish to thank Bing Powell, Charles Ragin, Mehran Kamrava, Bonnie Meguid, Gretchen Helmeke, and participants in the Comparative Politics Workshop at the University of Rochester for helpful suggestions and comments. 2Department of Economics, University of Miami, Jenkins Bldg., Coral Gables, FL 33146. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Some theories of revolution deny an independent role for ideology in the making of rev- olutions, whereas others grant it an indispensable role. I investigate the role of ideology in the Iranian Revolution by focusing on two periods of Iranian history that witnessed popular uprising: the early 1960's and the late 1970's. While the former uprising was aborted, the latter led to the Iranian Revolution. Contrasting these periods, I argue that the structural and non-agency process factors underwent the same dynamic in both periods, and hence are not sufficient to explain the variation in outcome. I propose that the change in the oppo- sition's ideology accounts for this variation. To establish the causal link, I investigate this ideological change, tracing its role in the actors' decision-making processes. I argue that: (1) Khomeini's theory of Islamic state expanded the set of alternatives to the status quo theory of state, and changed the Islamic opposition's \calculus of protest"; (2) an ideological change is an intellectual innovation/shock, the timing of which is intrinsically uncertain. Therefore, integrating ideology to the theory enhances its explanatory power; (3) an ideological change can serve as an observable intermediate variable that mediates the effect of unobservable cumulative and/or threshold processes. -

Post-Islamism a New Phase Or Ideological

Post-Islamism A New Phase or Ideological Delusions? 2 Post - Islamism The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan The Deposit Number at The National Library (2018/12/6029) 324.2182 AbuRumman, Mohammad Suliman Post Islamism: A New Phase or Ideological Delusions?/ Mohammad Sulima- nAbuRumman; translated by William Joseph Ward. – Amman: Friedrich- Ebert-Stiftung, 2018 (232) p. Deposit No.: 2018/12/6029 Descriptors: /Religious Parties//Political Parties// Arab Countries/ ﻳﺘﺤﻤﻞ اﳌﺆﻟﻒ ﻛﺎﻣﻞ اﳌﺴﺆﻭﻟﻴﺔ اﻟﻘﺎﻧﻮﻧﻴﺔ ﻋﻦ ﳏﺘﻮ ﻣﺼﻨﻔﻪ ﻭﻻ ﹼﻳﻌﱪ ﻫﺬا اﳌﺼﻨﻒ ﻋﻦ رأﻱ داﺋﺮة اﳌﻜﺘﺒﺔ اﻟﻮﻃﻨﻴﺔ أﻭ أﻱ ﺟﻬﺔ ﺣﻜﻮﻣﻴﺔ أﺧﺮ. Published in 2018 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Jordan & Iraq FES Jordan & Iraq P.O. Box 941876 Amman11194 Jordan Email:[email protected] Website:www.fes-jordan.org Not for Sale © FES Jordan & Iraq All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the original author. They do not necessarily represent those of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung or the editor. Translation: Industry Arabic Cover design: Yousef Saraireh Lay-out: Eman Khattab Printing: Economic Press ISBN: 978-9957-484-91-0 Foreword 3 Post-Islamism A New Phase or Ideological Delusions? Editor: Dr. Mohammed Abu Rumman 4 Post - Islamism Foreword 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 7 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 — Post-Islamism: Problems of the Term and Concept 21 Study 1: From Islamism to Post-Islamism: An Examination of Concepts and Theses, Hassan Abu Hanieh 23 Study 2: “Post-Islamism”: Lessons from Arab Revolutions, Luz Gómez 57 Study 3: The Failure of Political Islam: Ideological Delusions and Socio- logical Realities, Dr. -

Portugal's History Since 1974

Portugal’s history since 1974 Stewart Lloyd-Jones ISCTE-Lisbon AN IMPERIAL LEGACY The Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos) that broke out on the morning of 25 April 1974 has had a profound effect on Portuguese society, one that still has its echoes today, almost 30 years later, and which colours many of the political decision that have been, and which continue to be made. During the authoritarian regime of António de Oliveira Salazar (1932-68) and his successor, Marcello Caetano (1968-74), Portugal had existed in a world of its own construction. Its vast African empire (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé e Príncipe, and Cape Verde) was consistently used to define Portugal’s self-perceived identity as being ‘in, but not of Europe’. Within Lisbon’s corridors of power, the dissolution of the other European empires was viewed with horror, and despite international opprobrium and increasing isolation, the Portuguese dictatorship was in no way prepared to follow the path of decolonisation. As Salazar was to defiantly declare, Portugal would stand ‘proudly alone’, indeed, for a regime that had consciously legitimated itself by ‘turning its back on Europe’, there could be no alternative course of action. Throughout the 1960s and early-1970s, the Portuguese people were to pay a high price for the regime’s determination to remain in Africa. From 1961 onwards, while the world’s attention was focused on events in south-east Asia, Portugal was fighting its own wars. By the end of the decade, the Portuguese government was spending almost half of its GNP on sustaining a military presence of over 150,000 troops in Africa. -

Not for Distribution

6 The decline of the legitimate monopoly of violence and the return of non-state warriors Cihan Tuğal Introduction For the last few decades, political sociology has focused on state-making. We are therefore quite ill equipped to understand the recent rise of non-state violence throughout the world. Even if states still seem to perform more violence than non- state actors, the latter’s actions have come to significantly transform relationships between citizens and states. Existing frameworks predispose scholars to treat non-state violence too as an instrument of state-building. However, we need to consider whether non-state violence serves other purposes as well. This chapter will first point out how the post-9/11 world problematises one of sociology’s major assumptions (the state’s monopolisation of legitimate violence). It will then trace the social prehistory of non-state political violence to highlight continui- ties with today’s intensifying religious violence. It will finally emphasise that the seemingly inevitable rise of non-state violence is inextricably tangled with the emergence of the subcontracting state. Neo-liberalisation aggravates the practico- ethical difficulties secular revolutionaries and religious radicals face (which I call ‘the Fanonite dilemma’ and ‘the Qutbi dilemma’). The monopolisation of violence: social implications War-making, military apparatuses and international military rivalry figure prominently in today’s political sociology. This came about as a reaction to the sociology and political science of the postwar era: for quite different rea- sons, both tended to ignore the influence of militaries and violence on domestic social structure. Political science unduly focused on the former and sociology on the latter, whereas (according to the new political sociology) international violence and domestic social structure are tightly linked (Mann 1986; Skocpol 1979; Tilly 1992). -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83720-0 - The Cambridge History of the Cold War: Crises and Détente: Volume II Edited by Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad Index More information Index Cumulative index for Volumes I, II, and III. Bold page numbers refer to maps and photographs. 9/11 attacks, III.134, 537, 550, 554–5 anti-Sovietism, I.150 Berlin crisis, II.168 abortion, III.468, 469, 473 Cuban missile crisis, II.73 Abstract Expressionism, II.30 division of Germany and, II.482–3 Accornero, Aris (Italian social scientist), I.54 European integration, II.182, 183–4 Achaeans, II.1 French relations, II.168, 169, 184 Acheson, Dean, I.78 German unification and, II.203 Acheson–Lilienthal Report, II.397 Khrushchev and, I.319 Excomm, II.71 loss of power, II.483 on Germany, II.119, III.156 Marshall Plan, I.170 grand strategy, I.84–6 NPT and, II.408 Ho Chi Minh and, I.82–3 nuclear weapons, II.487 Japanese policy, I.82, III.156 US relations, II.484 Korean War, I.276 values, II.462–3 Marshall Plan and, I.155, 159 Advanced Research Projects Agency, see NATO, I.81 ARPA Pacific policy, I.274 advertising, III.503, 504–5 political influence, I.83 Adzhubei, Aleksei (Soviet journalist), III.402 postwar assessment, I.74 affluent society, II.510–13, 518 on racial segregation, I.433–4, III.456 Afghanistan Schuman Plan and, II.182 Al Qaeda, III.133–4 Ackermann, Anton (German Communist), bibliography, III.566 I.180 Cold War and, I.484 Acton, John (British historian) I.1, 2 Egyptian relations, III.126 Adamec, Ladislav (Czechoslovak prime fundamentalism, III.536–7