Not for Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion and Politics

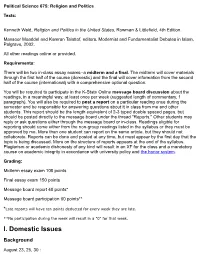

Political Science 675: Religion and Politics Texts: Kenneth Wald, Religion and Politics in the United States, Rowman & Littlefield, 4th Edition. Mansoor Moaddel and Kamran Talattof, editors, Modernist and Fundamentalist Debates in Islam, Palgrave, 2002. All other readings online or provided. Requirements: There will be two in-class essay exams--a midterm and a final. The midterm will cover materials through the first half of the course (domestic) and the final will cover information from the second half of the course (international) with a comprehensive optional question. You will be required to participate in the K-State Online message board discussion about the readings, in a meaningful way, at least once per week (suggested length of commentary, 1 paragraph). You will also be required to post a report on a particular reading once during the semester and be responsible for answering questions about it in class from me and other students. This report should be the length equivalent of 2-3 typed double spaced pages, but should be posted directly to the message board under the thread "Reports." Other students may reply or ask questions either through the message board or in-class. Readings eligible for reporting should come either from the non-group readings listed in the syllabus or they must be approved by me. More than one student can report on the same article, but they should not collaborate. Reports can be done and posted at any time, but must appear by the first day that the topic is being discussed. More on the structure of reports appears at the end of the syllabus. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Learning to Swim in Stormy Weather” Was first Published July 31, 2011, at Winterends.Net

Greece’s Communist Organization: LearningLearning toto SwimSwim inin StormyStormy WeatherWeather by Eric Ribellarsi Also includes “The in!uence of the Chinese Revolution on the Communist Movement of Greece” by the Communist Organization of Greece (KOE), 2006 KASAMA ESSAYS FOR DISCUSSION “Greece’s Communist Organization: Learning to Swim in Stormy Weather” was first published July 31, 2011, at winterends.net. Winter Has Its End is a team of reporters traveling during the summer of 2011 to places in the world where people are rising up. “!e influence of the Chinese Revolution on the Communist Move- ment of Greece” was published by the Communist Organization of Greece (KOE), May 2006 Published as a Kasama Essay for Discussion pamphlet August, 2011 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States Licence. Feel free to reprint, distribute or quote this with attribution. Cover photo illustration by Enzo Rhyner/original photo by Eric Ribellarsi Kasama is a communist project that seeks to reconceive and regroup for a profound revolutionary transformation of society. website: kasamaproject.org email: [email protected] 80045_r2 08.11 Greece’s Communist Organization: Learning to Swim in Stormy Weather by Eric Ribellarsi We in Kasama, and many others, have been en- Great and energetic hopes often masked under- gaged for several years now in trying to imagine new lying naiveté and fracture lines that would inevitably ways to fuse revolutionary ideas with the popular dis- come to the fore: How should these popular move- content of the people. It is part of what drew our Win- ments view the existing army (in Egypt), or the intru- ter’s End reporti ng team to Greece and what draws sive Western powers (in Libya), or problems of defin- us now to discuss the Communist Organization of ing specific solutions, or the organizational problems Greece (known as the KOE, and pronounced ‘Koy’). -

The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Legacies

1 The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Legacies Vladimir Tismaneanu The revolutions of 1989 were, no matter how one judges their nature, a true world-historical event, in the Hegelian sense: they established a historical cleavage (only to some extent conventional) between the world before and after 89. During that year, what appeared to be an immutable, ostensibly indestructible system collapsed with breath-taking alacrity. And this happened not because of external blows (although external pressure did matter), as in the case of Nazi Germany, but as a consequence of the development of insuperable inner tensions. The Leninist systems were terminally sick, and the disease affected first and foremost their capacity for self-regeneration. After decades of toying with the ideas of intrasystemic reforms (“institutional amphibiousness”, as it were, to use X. L. Ding’s concept, as developed by Archie Brown in his writings on Gorbachev and Gorbachevism), it had become clear that communism did not have the resources for readjustment and that the solution lay not within but outside, and even against, the existing order.1 The importance of these revolutions cannot therefore be overestimated: they represent the triumph of civic dignity and political morality over ideological monism, bureaucratic cynicism and police dictatorship.2 Rooted in an individualistic concept of freedom, programmatically skeptical of all ideological blueprints for social engineering, these revolutions were, at least in their first stage, liberal and non-utopian.3 The fact that 1 See Archie Brown, Seven Years that Changed the World: Perestroika in Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 157-189. In this paper I elaborate upon and revisit the main ideas I put them forward in my introduction to Vladimir Tismaneanu, ed., The Revolutions of 1989 (London and New York: Routledge, 1999) as well as in my book Reinventing Politics: Eastern Europe from Stalin to Havel (New York: Free Press, 1992; revised and expanded paperback, with new afterword, Free Press, 1993). -

Gabriel Martin Telleria Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The

FROM VANDALS TO VANGUARD:VANGUARDISM THROUGH A NEOINSTITUTIONAL LENS: CASE STUDY OF THE SANDINISTA NATIONAL LIBERATION FRONT Gabriel Martin Telleria Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Public Administration and Public Affairs Dissertation Committee: Larkin S. Dudley, Chair Karen M. Hult Laura S. Jensen Sergio Ramírez Mercado James F. Wolf April 6, 2011 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Vanguardism, Sandinistas, FSLN, politico-military organizations, institutionalization Copyright 2011, Gabriel Martin Telleria FROM VANDALS TO VANGUARD:VANGUARDISM THROUGH A NEOINSTITUTIONAL LENS: CASE STUDY OF THE SANDINISTA NATIONAL LIBERATION FRONT GABRIEL MARTÍN TELLERIA MALTÉS ABSTRACT The Sandinista Revolution is arguably the most significant event in Nicaraguan history. Because of its historical importance and distinctive socio-cultural context, the Sandinista Revolution offers significant opportunities for scholarly inquiry. The literature on the Sandinista Revolution is substantial. However, little is known about the organization Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) and how it evolved into the leader of the movement which sought to overthrow the 45-year Somoza dictatorship. In revolutionary literature, the concept of revolutionary vanguard or vanguard party is common. However, the notion of vanguardism as a process and what constitutes a vanguardist organization is yet to be explored. This study aims to provide such an investigation, through an examination of the insurrectional period (1974-1979) leading up to the Sandinista Revolutionary Victory in 1979. Grounded in Scott’s (2008) institutional framework, this study describes the evolution of the FSLN into the vanguard of the anti-Somoza movement, identifying relationships between institutional elements involved in the FSLN’s institutionalization process and progression into “leader” of the movement. -

Chile's Democratic Road to Socialism

CHILE'S DEMOCRATIC ROAD TO SOCIALISM: THE RISE AND FALL OF SALVADOR ALLENDE, 1970-1973. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History in the University of Canterbury by Richard Stuart Mann University of Canterbury 1980 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the Chilean experience of a democratic road to socialism, initiated with the election of Salvador Allende as president in 1970 and ending with his overthrow by the Chilean armed forces in 1973. The interplay of political, economic and cultural variables is considered and an effort is made to assess their relative significance concerning the failure of la via chilena. Allende's Popular Unity government was within the tradition$ of Chilean history since 1930: leftist electoral participation and popular support, respect £or the democratic system, state direction in the economy, ideological competit ion and the political attempt to resolve continuing socio- economic problems. Chile was politically sophisticated but economically underdeveloped. In a broader sense, th~ L:e.ft sought complete independence £or Chile and a genuine national identity. U.S. involvement is therefore examined as a continuing theme in perceptions 0£ Chilean history. The seeds 0£ Popular Unity's downfall were as much inherent in the contradiction between an absolute ideology and a relative political strength as in the opposition 0£ those with a vested interest in the existing system. Indeed, the Left itself was a part 0£ that system. Popular Unity went a considerable way in implementing its policies, but the question of power was not resolved as the political forces became stalemated. -

Revolution in Bad Times

asef bayat REVOLUTION IN BAD TIMES ack in 2011, the Arab uprisings were celebrated as world- changing events that would re-define the spirit of our political times. The astonishing spread of these mass uprisings, fol- lowed soon after by the Occupy protests, left observers in Blittle doubt that they were witnessing an unprecedented phenomenon— ‘something totally new’, ‘open-ended’, a ‘movement without a name’; revolutions that heralded a novel path to emancipation. According to Alain Badiou, Tahrir Square and all the activities which took place there—fighting, barricading, camping, debating, cooking and caring for the wounded—constituted the ‘communism of movement’; posited as an alternative to the conventional liberal-democratic or authoritar- ian state, this was a universal concept that heralded a new way of doing politics—a true revolution. For Slavoj Žižek, only these ‘totally new’ political happenings, without hegemonic organizations, charismatic leaderships or party apparatuses, could create what he called the ‘magic of Tahrir’. For Hardt and Negri, the Arab Spring, Europe’s indignado protests and Occupy Wall Street expressed the longing of the multitude for a ‘real democracy’, a different kind of polity that might supplant the hopeless liberal variety worn threadbare by corporate capitalism. These movements, in sum, represented the ‘new global revolutions’.1 ‘New’, certainly; but what does this ‘newness’ tell us about the nature of these political upheavals? What value does it attribute to them? In fact, just as these confident appraisals were being circulated in the us and Europe, the Arab protagonists themselves were anguishing about the fate of their ‘revolutions’, lamenting the dangers of conservative restora- tion or hijacking by free-riders. -

The Success of the Nicaraguan Revolution: Why and How?

Ibero-Americana, Nordic Journal of Latin American Studies Vol. XI: 1-2, 1982, pp. 3-16 THE SUCCESS OF THE NICARAGUAN REVOLUTION: WHY AND HOW? VEGARD BYE In the following paper, I shall try to discuss some of the elements I see as being decisive for the revolutionary victory in Nicaragua. Where appropiate, I shall make comparisons to the Castro-movement in Cuba. A fundamental question will of course be why this strategy succeeded in Cuba and Nicaragua, while it failed in so many other countries. In this discussion, I shall not go into the characteristics and particularities of the imminent socio-economic and political crisis paving the way for the revolutionary situation. It is taken for granted that a profound crisis in this respect has been pre vailing in most countries where guerrilla strategies were attempted. What is dis cussed here, is how the FSLN (Sandinist Front of National Liberation), compared with other guerrilla movements, has answered this crisis and built its revolutionary strategies. This is not to propose that a complete analysis of the Nicaraguan revolu tion can exclude a detailed analysis of the character of the crisis of Somozist Nicara gua and the particularities of the Sandinist answer to this crisis, but such an analysis is beyond the scope of this article. 1 I. The Castroist guerrilla tradition In a study of guerrilla strategies in Latin America carried out at the German Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Robert F. Lamberg distinguishes among three steps in the ideological and strategic development of what he calls the Castroist guerrilla after 1 A good - though quite brief - analysis of the socio-economic crisis of Somozist Nica ragua is to be found in Herrera Zuniga, Rene, "Nicaragua: el desarrollo capitalista depen diente y la crisis de la dominaci6n burguesa, 1950-1980", in Centroamerica en crisis, Centro de Estudios Internacionales, El Colegio de Mexico, 1980, pp. -

Restructuring the Socialist Economy

CAPITAL AND CLASS IN CUBAN DEVELOPMENT: Restructuring the Socialist Economy Brian Green B.A. Simon Fraser University, 1994 THESISSUBMllTED IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMEW FOR THE DEGREE OF MASER OF ARTS Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies O Brian Green 1996 All rights resewed. This work my not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Siblioth&ye nationale du Canada Azcjuis;lrons and Direction des acquisitions et Bitjibgraphic Sewices Branch des services biblicxpphiques Youi hie Vofrergfereoce Our hie Ncfre rb1Prence The author has granted an L'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive ficence irrevocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant & la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationafe du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, preter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes int6ress6es. The author retains ownership of L'auteur consenre la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial th&se. Ni la thbe ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiefs de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent 6tre imprimes ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisatiow. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Sion Fraser Universi the sight to Iend my thesis, prosect or ex?ended essay (the title o7 which is shown below) to users o2 the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the Zibrary of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

The American Taboo on Socialism by Robert N. Bellah Ocialism Arose in Europe As a Critique of Industrial Society Early in the 19

The American Taboo on Socialism By Robert N. Bellah Chapter V in Robert N. Bellah, The Broken Covenant: American Civil Religion in Time of Trial, Second Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 112-138. The University of Chicago Press granted permission to include this chapter on www.robertbellah.com. Copyright © 1975, 1992 by the Robert N. Bellah 1984 Trust. All rights reserved. A version of this essay was also published as “Roots of the American Taboo” in The Nation, December 28, 1974, Vol. 219, No. 22, pp. 677-685. ocialism arose in Europe as a critique of industrial society early in the 19th century. A sig- S nificant socialist movement exists in almost every industrial nation in the world, often going back a century or more. Socialism as an ideology is important in most of the nonindustrial nations as well. Among the major industrial nations, only America has no significant socialist movement. Although socialism was introduced to America early in its history, there is only a fragmentary socialist tradition here. The criticism of capitalism, vigorous in most industrial na- tions, has been faint and fitful. Why is it that socialism has been taboo, and capitalism sacrosanct? Is it because capital- ism has “worked” in America? Is it because capitalism‟s beneficiaries have outnumbered its vic- tims? Perhaps though it has worked for some groups better than for others and in some periods better than in others. And it is not obvious that capitalism has worked so much better here than in many other countries where it has met a strenuous opposition. -

A Century of 1917S: Ideas, Representations, and Interpretations of the October Revolution, 1917–2017 * Andrea Graziosi

Harvard Ukrainian Studiesa 36, century no. 1–2 (2019):of 1917s 9–44. 9 ONE HUNDRED YEARS AFTER THE REVOLUTION A Century of 1917s: Ideas, Representations, and Interpretations of the October Revolution, 1917–2017 * Andrea Graziosi Introduction he celebrations of the 1917 centenary were striking for both their diversity and the diminishment of the event they commemorated, Tfrom Moscow’s low-key celebrations,1 to the missing or halfhearted remembrances organized in the former Soviet and socialist countries, to the West’s many platitudes—all of them stridently contradicting the initial energy of 1917. Embarrassment and hollowness were the key words in Russia, where, in 2017, 1917 was presented either as a “world historical event” illustrating the country’s greatness and importance by the very fact that it had taken place there, or it was buried under occasional studies of local events, with very little room left over for ideas. In the remain- ing post-Soviet states, as well as in the former socialist countries, silence often fell on what was until recently a hot terrain of polemics * This essay is based on a lecture that I delivered at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute on 6 November 2017, “Rethinking the 1917 Revolution,” as well as on a presentation that I gave at the 100th Anniversary Roundtable “The Bolshevik Revolution and Its Legacy in the USSR, Post-Soviet Russia, and the West,” organized by the Davis Center on the following day. The idea for this essay came from the way I reconstructed the interpretations of the Soviet experience in the chapter “What is the Soviet Union?” in my Histoire de l’URSS (Paris: PUF, 2010; Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2016). -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief.