Portugal and England, 1386-2010 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mundial.Com Navegantecultural

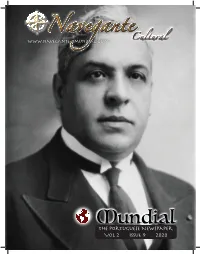

This is your outside front cover (OFC). The red line is the bleed area. www.navegante-omundial.com NaveganteCultural MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Vol 2 Issue 9 2020 This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. This is your inside front cover (IFC). This can be your Masthead page, with a Letter from the editor and table of contents, or, whatever you This is where you would normally place a full page ad etc. need or want it to contain. You can make the letter or table of contents any size/depth you need it to be. The red line is the bleed area. You can also have Letter and/or Contents on a different page from the Masthead. Letter from the Editor MundialThe Portuguese Newspaper Aristides de Sousa One of those measures was the right of refusal Mendes saved the for consular officials to grant or issue Visas, set PUBLISHER / EDITORA lives of thousands first in Circular Number 10, and reinforced a Navegante Cultural Navigator of Jews fleeing the year later by Circular Number 14 in 1939. 204.981.3019 Nazis during his tenure as Portuguese At the same time, in reaction to the Consul in Bordeaux, Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany, in early EDITOR-IN-CHIEF France. -

The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: from Inception To

THE PORTUGUESE EXPEDITIONARY CORPS IN WORLD WAR I: FROM INCEPTION TO COMBAT DESTRUCTION, 1914-1918 Jesse Pyles, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Robert Citino, Committee Member Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pyles, Jesse, The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: From Inception to Destruction, 1914-1918. Master of Arts (History), May 2012, 130 pp., references, 86. The Portuguese Expeditionary Force fought in the trenches of northern France from April 1917 to April 1918. On 9 April 1918 the sledgehammer blow of Operation Georgette fell upon the exhausted Portuguese troops. British accounts of the Portuguese Corps’ participation in combat on the Western Front are terse. Many are dismissive. In fact, Portuguese units experienced heavy combat and successfully held their ground against all attacks. Regarding Georgette, the standard British narrative holds that most of the Portuguese soldiers threw their weapons aside and ran. The account is incontrovertibly false. Most of the Portuguese combat troops held their ground against the German assault. This thesis details the history of the Portuguese Expeditionary Force. Copyright 2012 by Jesse Pyles ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The love of my life, my wife Izabella, encouraged me to pursue graduate education in history. This thesis would not have been possible without her support. Professor Geoffrey Wawro directed my thesis. He provided helpful feedback regarding content and structure. Professor Robert Citino offered equal measures of instruction and encouragement. -

Contradictions of the Estado Novo in the Modernisation of Portugal: Design and Designers in the 1940'S and 50'S

“Design Policies: Between Dictatorship and Resistance” | December 2015 Edition CONTRADICTIONS OF THE ESTADO NOVO IN THE MODERNISATION OF PORTUGAL: DESIGN AND DESIGNERS IN THE 1940'S AND 50'S Helena Barbosa, Universidade de Aveiro ABSTRACT The period of Portuguese history known as the Estado Novo (1933-1974) presents a series of contradictions as regards the directives issued, possibly resulting from a lack of political cohesion. Considering the dichotomy between modernization and tradition that existed between the 1940s and ‘50s, and the obvious validity of the government’s actions, this paper aims to demonstrate the contradictory attitudes towards the modernization of the country via different routes, highlighting the role of ‘designers’ as silent interlocutors and agents of change in this process. Various documents are analysed, some published under the auspices of the Estado Novo, others in the public sphere, in order to reveal the various partnerships that were in operation and the contrasting attitudes towards the government at the time. Other activities taking place in the period are also analysed, both those arising from state initiatives and others that were antithetical to it. The paper reveals the need to break with the political power in order to promote artistic and cultural interests, and describes initiatives designed to promote industry in the country, some launched by the Estado Novo, others by companies. It focuses upon the teaching of art, which later gave rise to the teaching of design, and on the presence of other institutions and organizations that contributed to the modernization of Portugal, in some cases by mounting exhibitions in Portugal and abroad, as well as other artistic activities such as graphic design, product design and interior decoration, referring to the respective designers, artefacts and spaces. -

Exile, Diplomacy and Texts: Exchanges Between Iberia and the British Isles, 1500–1767

Exile, Diplomacy and Texts Intersections Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture General Editor Karl A.E. Enenkel (Chair of Medieval and Neo-Latin Literature Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster e-mail: kenen_01@uni_muenster.de) Editorial Board W. van Anrooij (University of Leiden) W. de Boer (Miami University) Chr. Göttler (University of Bern) J.L. de Jong (University of Groningen) W.S. Melion (Emory University) R. Seidel (Goethe University Frankfurt am Main) P.J. Smith (University of Leiden) J. Thompson (Queen’s University Belfast) A. Traninger (Freie Universität Berlin) C. Zittel (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice / University of Stuttgart) C. Zwierlein (Freie Universität Berlin) volume 74 – 2021 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/inte Exile, Diplomacy and Texts Exchanges between Iberia and the British Isles, 1500–1767 Edited by Ana Sáez-Hidalgo Berta Cano-Echevarría LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. This volume has been benefited from financial support of the research project “Exilio, diplomacia y transmisión textual: Redes de intercambio entre la Península Ibérica y las Islas Británicas en la Edad Moderna,” from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación, the Spanish Research Agency (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad). -

Medieval Portuguese Royal Chronicles. Topics in a Discourse of Identity and Power

Medieval Portuguese Royal Chronicles. Topics in a Discourse of Identity and Power Bernardo Vasconcelos e Sousa Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Universidade Nova de Lisboa [email protected] Abstract It is only in the 15th century that the Portuguese royal chronicles assume their own unequivocal form. The following text analyses them as a discourse of the identity and power of the Crown. Three topics are selected by their importance and salience. These topics are the territory object of observation, the central subject of the narrative and the question of the authors of the historiographical accounts, or rather the position in which the chroniclers place themselves and the perspective they adopt for their description of events. Key words Portugal, historiography, medieval chronicles Resumo É apenas no século XV que a cronística régia portuguesa ganha a sua forma inequívoca. No texto seguinte analisam-se as respectivas crónicas como um discurso de identidade e de poder da Coroa. Assim, são seleccionados três tópicos pela sua importância e pelo relevo que lhes é dado. São eles o território objecto de observação, o sujeito central da narrativa e a questão dos autores dos relatos historiográficos, ou seja a posição em que os cronistas se colocam e a perspectiva que adoptam na descrição que fazem dos acontecimentos. Palavras-chave Portugal, historiografia, cronística medieval The medieval royal chronicle genre constitutes an accurate type of historiography in narrative form, promoted by the Crown and in which the central protagonist is the monarchy (usually the king himself, its supreme exponent). The discourse therefore centers on the deeds of the monarch and on the history of the royal institution that the king and his respective dynasty embody. -

Óscar Perea Rodríguez Ehumanista: Volume 6, 2006 237 Olivera

Óscar Perea Rodríguez 237 Olivera Serrano, César. Beatriz de Portugal. La pugna dinástica Avís-Trastámara. Prologue by Eduardo Paro de Guevara y Valdés. Santiago de Compostela: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas-Xunta de Galicia-Instituto de Estudios Gallegos “Padre Sarmiento”, 2005 (Cuadernos de Estudios Gallegos, Anexo XXXV), págs. 590. ISBN 84-00-08343-1 Reviewed by Óscar Perea Rodríguez University of California, Berkeley In his essays, Miquel Batllori often argued that scholars researching Humanism should pay particular attention to the 15th century in order to gain a better understanding of the 16th century. This has been amply achieved by César Olivera Serrano, author of the book reviewed here, for in it he has offered us remarkable insight into 15th-century Castilian history through an extraordinary analysis of 14th-century history. As Professor Pardo de Guevara points out in his prologue, this book is an in-depth biographical study of Queen Beatriz of Portugal (second wife of the King John I of Castile). Additionally, it is also an analysis of the main directions of Castilian foreign policy through the late 14th and 15th centuries and of how Castile’s further political and economic development was strictly anchored in its 14th-century policies. The first chapter, entitled La cuestionada legitimidad de los Trastámara, focuses on Princess Beatriz as the prisoner of her father’s political wishes. King Ferdinand I of Portugal wanted to take advantage of the irregular seizure of the Castilian throne by the Trastámara family. Thus, he offered himself as a candidate to Castile’s crown, sometimes fighting for his rights in the battlefield, sometimes through peace treatises. -

Portugal 1 EL**

CULTUREGUIDE PORTUGAL SERIES 1 PRIMARY (K–6) Photo by Anna Dziubinska Anna by on Unsplash Photo PORTUGAL CULTUREGUIDE This unit is published by the International Outreach Program of the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies at Brigham Young University as part of an effort to foster open cultural exchange within the educational community and to promote increased global understanding by providing meaningful cultural education tools. Curriculum Development Drew Cutler served as a representative of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in northern Portugal. He was a 2001 Outreach participant majoring in international studies and Latin American studies. Editorial Staff Content Review Committee Victoria Blanchard, CultureGuide Jeff Ringer, director publications coordinator Cory Leonard, assistant director International Outreach David M. Kennedy Center Editorial Assistants Ana Loso, program coordinator Leticia Adams International Outreach Linsi Barker Frederick Williams, professor of Spanish Lisa Clark and Portuguese Carrie Coplen Mark Grover, Latin American librarian Michelle Duncan Brigham Young University Krista Empey Jill Fernald Adrianne Gardner Anvi Hoang Amber Marshall Christy Shepherd Ashley Spencer J. Lee Simons, editor Kennedy Center Publications For more information on the International Outreach program at Brigham Young University, contact International Outreach, 273 Herald R. Clark Building, PO Box 24537, Provo, UT 84604- 9951, (801) 422-3040, [email protected]. © 2004 International Outreach, David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602. Material contained in this packet may be reproduced for single teacher use in the classroom as needed to present the enclosed lessons; the packet is not to be reproduced and distributed to other teachers. -

Portugal's History Since 1974

Portugal’s history since 1974 Stewart Lloyd-Jones ISCTE-Lisbon AN IMPERIAL LEGACY The Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos) that broke out on the morning of 25 April 1974 has had a profound effect on Portuguese society, one that still has its echoes today, almost 30 years later, and which colours many of the political decision that have been, and which continue to be made. During the authoritarian regime of António de Oliveira Salazar (1932-68) and his successor, Marcello Caetano (1968-74), Portugal had existed in a world of its own construction. Its vast African empire (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé e Príncipe, and Cape Verde) was consistently used to define Portugal’s self-perceived identity as being ‘in, but not of Europe’. Within Lisbon’s corridors of power, the dissolution of the other European empires was viewed with horror, and despite international opprobrium and increasing isolation, the Portuguese dictatorship was in no way prepared to follow the path of decolonisation. As Salazar was to defiantly declare, Portugal would stand ‘proudly alone’, indeed, for a regime that had consciously legitimated itself by ‘turning its back on Europe’, there could be no alternative course of action. Throughout the 1960s and early-1970s, the Portuguese people were to pay a high price for the regime’s determination to remain in Africa. From 1961 onwards, while the world’s attention was focused on events in south-east Asia, Portugal was fighting its own wars. By the end of the decade, the Portuguese government was spending almost half of its GNP on sustaining a military presence of over 150,000 troops in Africa. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early M

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 © Copyright by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia by Sara Victoria Torres Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Christine Chism, Co-chair Professor Lowell Gallagher, Co-chair My dissertation, “Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia,” traces the legacy of dynastic internationalism in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and early-seventeenth centuries. I argue that the situated tactics of courtly literature use genealogical and geographical paradigms to redefine national sovereignty. Before the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, before the divorce trials of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon in the 1530s, a rich and complex network of dynastic, economic, and political alliances existed between medieval England and the Iberian kingdoms. The marriages of John of Gaunt’s two daughters to the Castilian and Portuguese kings created a legacy of Anglo-Iberian cultural exchange ii that is evident in the literature and manuscript culture of both England and Iberia. Because England, Castile, and Portugal all saw the rise of new dynastic lines at the end of the fourteenth century, the subsequent literature produced at their courts is preoccupied with issues of genealogy, just rule, and political consent. Dynastic foundation narratives compensate for the uncertainties of succession by evoking the longue durée of national histories—of Trojan diaspora narratives, of Roman rule, of apostolic foundation—and situating them within universalizing historical modes. -

International Literary Program

PROGRAM & GUIDE International Literary Program LISBON June 29 July 11 2014 ORGANIZATION SPONSORS SUPPORT GRÉMIO LITERÁRIO Bem-Vindo and Welcome to the fourth annual DISQUIET International Literary Program! We’re thrilled you’re joining us this summer and eagerly await meeting you in the inimitable city of Lisbon – known locally as Lisboa. As you’ll soon see, Lisboa is a city of tremendous vitality and energy, full of stunning, surprising vistas and labyrinthine cobblestone streets. You wander the city much like you wander the unexpected narrative pathways in Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, the program’s namesake. In other words, the city itself is not unlike its greatest writer’s most beguiling text. Thanks to our many partners and sponsors, traveling to Lisbon as part of the DISQUIET program gives participants unique access to Lisboa’s cultural life: from private talks on the history of Fado (aka The Portuguese Blues) in the Fado museum to numerous opportunities to meet with both the leading and up-and- coming Portuguese authors. The year’s program is shaping up to be one of our best yet. Among many other offerings we’ll host a Playwriting workshop for the first time; we have a special panel dedicated to the Three Marias, the celebrated trio of women who collaborated on one of the most subversive books in Portuguese history; and we welcome National Book Award-winner Denis Johnson as this year’s guest writer. Our hope is it all adds up to a singular experience that elevates your writing and affects you in profound and meaningful ways. -

Prince Henry the Navigator, Who Brought This Move Ment of European Expansion Within Sight of Its Greatest Successes

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com PrinceHenrytheNavigator CharlesRaymondBeazley 1 - 1 1 J fteroes of tbe TRattong EDITED BY Sveltn Bbbott, flD.B. FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD PACTA DUOS VIVE NT, OPEROSAQUE OLMIA MHUM.— OVID, IN LI VI AM, f«». THE HERO'S DEEDS AND HARD-WON FAME SHALL LIVE. PRINCE HENRY THE NAVIGATOR GATEWAY AT BELEM. WITH STATUE, BETWEEN THE DOORS, OF PRINCE HENRY IN ARMOUR. Frontispiece. 1 1 l i "5 ' - "Hi:- li: ;, i'O * .1 ' II* FV -- .1/ i-.'..*. »' ... •S-v, r . • . '**wW' PRINCE HENRY THE NAVIGATOR THE HERO OF PORTUGAL AND OF MODERN DISCOVERY I 394-1460 A.D. WITH AN ACCOUNr Of" GEOGRAPHICAL PROGRESS THROUGH OUT THE MIDDLE AGLi> AS THE PREPARATION FOR KIS WORlf' BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, M.A., F.R.G.S. FELLOW OF MERTON 1 fr" ' RifrB | <lvFnwn ; GEOGRAPHICAL STUDEN^rf^fHB-SrraSR^tttpXFORD, 1894 ule. Seneca, Medea P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON Cbe Knicftetbocftet press 1911 fe'47708A . A' ;D ,'! ~.*"< " AND TILDl.N' POL ' 3 -P. i-X's I_ • •VV: : • • •••••• Copyright, 1894 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Ube ftntcfeerbocfter press, Hew Iffotfc CONTENTS. PACK PREFACE Xvii INTRODUCTION. THE GREEK AND ARABIC IDEAS OF THE WORLD, AS THE CHIEF INHERITANCE OF THE CHRISTIAN MIDDLE AGES IN GEOGRAPHICAL KNOWLEDGE . I CHAPTER I. EARLY CHRISTIAN PILGRIMS (CIRCA 333-867) . 29 CHAPTER II. VIKINGS OR NORTHMEN (CIRCA 787-1066) . -

Censura, Nunca Mais?

CENSURA, NUNCA MAIS? ESTUDOS DE CASO DURANTE O PREC 1 PAULO CUNHA CENTRO DE ESTUDOS INTERDISCIPLINARES DO SÉCULO XX DA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA (CEIS20/ UC) MARIA DO CARMO PIÇARRA CENTRO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO MEDIA E JORNALISMO DA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS E HUMANAS DA UNIVERSIDADE NOVA DE LISBOA (CIMJ/ FCSH-UNL) Resumo Quando, após a Revolução dos Cravos e a abolição da censura, em Portugal, uma Comissão Ad Hoc foi criada, para “evitar o uso indevido de uma liberdade que tem de ser responsável”, dois filmes viram a sua estreia ser adiada: Sambizanga, de Sarah Maldoror, e Saló ou os 120 dias de Sodoma, de Pasolini. Uma obra de militância anticolonial, no primeiro caso; uma refle- xão violentíssima sobre o fascismo e a sua natureza repressora, no segundo. Politicamente, que condições existiam para uma análise sobre a longevidade da ditadura - 48 anos – e do colonia- lismo português e para dar uma resposta desassombrada à pergunta “Portugal, que futuro?” Estes estudos de caso ilustram o que José Gil chamou “o medo de existir”? Palavras-chave: Censura; Fascismo; Militância anticolonial; Pornografia; Opressão. Abstract When, after the Carnation Revolution and the abolition of censorship in Portugal, an Ad Hoc Committee was created to "prevent misuse of freedom that have to be responsible," two films saw their debut delayed: Sambizanga of Sarah Maldoror, and Salo ou os 120 dias de So- doma, Pasolini. A work of anticolonial militancy in the first case, a violent reflection on fascism and its repressive nature, on the second. Politically, what conditions existed for an analysis on the longevity of the dictatorship - 48 years - and Portuguese colonialism and fearless to give an answer to the question "Portugal, what future?" These case studies illustrate what José Gil called the "fear of existing "? Keywords: Censorship; Fascism; Anticolonial militancy; Pornography; Opression.