Mascarenhas, Mira. 1988. Impact of the West on Go

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Commercial Study of TIATR As a Form of Entertainment in Goa (India

A Commercial Study of TIATR as a form of Entertainment in Goa (India): An Empirical Analysis Dr.Juao Costa Associate Professor, Rosary College of Commerce and Arts, Navelim, Salcete, Goa. 403707. Abstract: Introduction: The state of Goa is rich in culture; heritage and art The state of Goa is rich in culture; heritage and art especially performing art in Goa is a unique feature of especially performing art in Goa is a unique feature of the state. Though all these forms fall under the wide the state. Though all these forms fall under the wide classification of dance, dramas and music yet the classification of dance, dramas and music yet the dance in Goa has a distinct Goan flavour and can be dance in Goa has a distinct Goan flavour and can be easily be distinguished from those of the other states. easily be distinguished from those of the other states. The most significant part about the performing arts in The most significant part about the performing arts in Goa is the fact that each of them colorfully illustrates Goa is the fact that each of them colourfully illustrates the unity in diversity of Goan heritage. Goan rich the unity in diversity of Goan heritage. Goan rich cultural heritage comprises of dance, folksongs, music cultural heritage comprises of dance, folksongs, music and folk tales rich in the content and variety. Goans are and folk tales rich in the content and variety. Goans are born music lovers. Goans are very fond of theatre and born music lovers. Goans are very fond of theatre and acting. -

PRODUCERS Sr

PRODUCERS Sr. Photo Name Address Category Contact No. Email ID Prasad Creations , SOI, 5th Allaparthi Durgaprasad 1 Floor,Milroc Lar Menezes, SV Road Producer 9822185804 [email protected] (National Awardee) Panjim 403001 Andre Agnelo Fernandes H. no. 52, Consua Verna, Salcete, 2 Producer 9850133861 [email protected] (State Awardee) Goa. 403722 H. No. 7, Opp. Merces Church, 3 Andre Brazinho De Souza Merces Vaddy, P.O. Santa Cruz, Producer 9822110396 [email protected] Illhas, Goa Angelo Braganza Agnelo House, H. No. 135, Mitra, 4 Producer 9664815065 [email protected] (National & State Awardee) Caranzalem, Illhas Goa. 205-F/1 , Boa Vista ,Bastora -Bardez 5 Anil Lad Producer 9326100075 [email protected] ,Goa Shri, H -7, Housing Board, Gogol, 6 Amar Sawant Producer 9730761270 [email protected] Margao. 403602 H.N.858, Opp Police Outpost, 7 Armando Fernandes Producer 7875801604 [email protected] Shiroda Ponda Goa.403103 Kurtarkar Gardens, Central Block E- 8 Ashutosh Khandekar 005, Opp. Anuradha Apts., Producer 9326104094 [email protected] Vidyanagar, Gogol, Margao, Goa 1st Floor, Alberto Castle, Opp Hotel 9 Atrey Sawant Producer 9850474882 [email protected] La Paz,Vasco Goa Telematics 1st floor, Flamingo Bld, 10 Augie D'Mello Near Old patto bridge, Near Hotel Producer 9326100211 [email protected] Sona/CMM, Panaji Goa. 403001 Bhalchandra Bakhale 'Swatyantra' near santosh garage, 11 Producer 9823628525 [email protected] (State Awardee) Aquem Margao Goa. Bonafacio Dias G1, Madel, Near the chapel, Margao, 12 Producer 9833515210 ______ (State Awardee) Goa. 173, Nagmodem, Navelim, Salcette 13 Claudio Colaco Producer 9822037228 [email protected] Goa 403707 H.No. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Goa University Glimpses of the 22Nd Annual Convocation 24-11-2009

XXVTH ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 asaicT ioo%-io%o GOA UNIVERSITY GLIMPSES OF THE 22ND ANNUAL CONVOCATION 24-11-2009 Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon ble President of India, arrives at Hon'ble President of India, with Dr. S. S. Sidhu, Governor of Goa the Convocation venue. & Chancellor, Goa University, Shri D. V. Kamat, Chief Minister of Goa, and members of the Executive Council of Goa University. Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon'ble President of India, A section of the audience. addresses the Convocation. GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 XXV ANNUAL REPORT June 2009- May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 CONTENTS Pg, No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3; ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY FACULTY INTRODUCTION 5 A: Seminars Organised 58 PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1.1 Members of Executive Council 6 C; ' Research Publications 72 D: Articles in Books 78 1.2 Members of University Court 6 E: Book Reviews 80 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ Conduct of Examinations 85 CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Library 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Sports 87 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Directorate of Students’ Welfare & 88 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. -

Lions Film Awards 01/01/1993 at Gd Birla Sabhagarh

1ST YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 01/01/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR TAPAS PAUL for RUPBAN BEST ACTRESS DEBASREE ROY for PREM BEST RISING ACTOR ABHISEKH CHATTERJEE for PURUSOTAM BEST RISING ACTRESS CHUMKI CHOUDHARY for ABHAGINI BEST FILM INDRAJIT BEST DIRECTOR BABLU SAMADDAR for ABHAGINI BEST UPCOMING DIRECTOR PRASENJIT for PURUSOTAM BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR MRINAL BANERJEE for CHETNA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER USHA UTHUP BEST PLAYBACK SINGER AMIT KUMAR BEST FILM NEWSPAPER CINE ADVANCE BEST P.R.O. NITA SARKAR for BAHADUR BEST PUBLICATION SUCHITRA FILM DIRECTORY SPECIAL AWARD FOR BEST FILM PREM TELEVISION BEST SERIAL NAGAR PARAY RUP NAGAR BEST DIRECTOR RAJA SEN for SUBARNALATA BEST ACTOR BHASKAR BANERJEE for STEPPING OUT BEST ACTRESS RUPA GANGULI for MUKTA BANDHA BEST NEWS READER RITA KAYRAL STAGE BEST ACTOR SOUMITRA CHATTERHEE for GHATAK BIDAI BEST ACTRESS APARNA SEN for BHALO KHARAB MAYE BEST DIRECTOR USHA GANGULI for COURT MARSHALL BEST DRAMA BECHARE JIJA JI BEST DANCER MAMATA SHANKER 2ND YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 24/12/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR CHIRANJEET for GHAR SANSAR BEST ACTRESS INDRANI HALDER for TAPASHYA BEST RISING ACTOR SANKAR CHAKRABORTY for ANUBHAV BEST RISING ACTRESS SOMA SREE for SONAM RAJA BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS RITUPARNA SENGUPTA for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST FILM AGANTUK OF SATYAJIT ROY BEST DIRECTOR PRABHAT ROY for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR BABUL BOSE for MON MANE NA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER INDRANI SEN for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER SAIKAT MITRA for MISTI MADHUR BEST CINEMA NEWSPAPER SCREEN BEST FILM CRITIC CHANDI MUKHERJEE for AAJKAAL BEST P.R.O. -

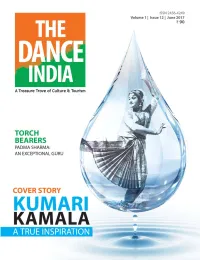

June 2017.Pmd

Torch Bearers Padma Sharma: CONTENTSCONTENTS An Exceptional Guru Cover 10 18 Story Rays of Kumari Kamala: 34 Hope A True Inspiration Dr Dwaram Tyagaraj: A Musician with a Big Heart Cultural Beyond RaysBulletin of Hope Borders The Thread of • Expressions34 of Continuity06 Love by Sri Krishna - Viraha Reviews • Jai Ho Russia! Reports • 4th Debadhara 52 Dance Festival • 5 Art Forms under One Roof 58 • 'Bodhisattva' steals the show • Resonating Naatya Tarang • Promoting Unity, Peace and Indian Culture • Tyagaraja's In Sight 250th Jayanthi • Simhapuri Dance Festival: A Celebrations Classical Feast • Odissi Workshop with Guru Debi Basu 42 64 • The Art of Journalistic Writing Tributes Beacons of light Frozen Mandakini Trivedi: -in-Time An Artiste Rooted in 63 Yogic Principles 28 61 ‘The Dance India’- a monthly cultural magazine in "If the art is poor, English is our humble attempt to capture the spirit and culture of art in all its diversity. the nation is sick." Editor-in-Chief International Coordinators BR Vikram Kumar Haimanti Basu, Tennessee Executive Editor Mallika Jayanti, Nebrasaka Paul Spurgeon Nicodemus Associate Editor Coordinators RMK Sharma (News, Advertisements & Subscriptions) Editorial Advisor Sai Venkatesh, Karnataka B Ratan Raju Kashmira Trivedi, Thane Alaknanda, Noida Contributions by Lakshmi Thomas, Chennai Padma Shri Sunil Kothari (Cultural Critic) Parinithi Gopal, Sagar Avinash Pasricha (Photographer) PSB Nambiar Sooryavamsham, Kerala Administration Manager Anurekha Gosh, Kolkata KV Lakshmi GV Chari, New Delhi Dr. Kshithija Barve, Goa and Kolhapur Circulation Manager V Srinivas Technical Advise and Graphic Design Communications Incharge K Bhanuji Rao Articles may be submitted for possible publication in the magazine in the following manner. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities Thesis Submitted to Goa University For the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English by Ms. Leanora Madeira née Pereira Under the Guidance of Prof. Nina Caldeira Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 August, 2020 CERTIFICATE I hereby certify that the thesis entitled “Identitarian Spaces of Goan Diasporic Communities” submitted by Ms. Leanora Pereira for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, has been completed under my supervision. The thesis is a record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other University. Prof. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. ii Declaration As required under the Ordinance OB 9A.9(v), I hereby declare that this thesis titled Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Professor Dr. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in this thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or any other titles awarded to me by this or any other university. Ms. Leanora Pereira Madeira Research Student Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 Date: August 2020 iii Acknowledgement The path God creates for each one of us is unique. I bow my head to the Almighty acknowledging him as the Alpha and the Omega and Lord of the Universe. -

Ketron A4 Fronte OOKK 2Biss

KETRON STYLES PACKAGE 2016 SD7 SD80 Midjpro For SD7 - SD80 • SD Styles / VOL.1 cod.9PDKP1 BALLAD COUNTRY DANCE 8Beat Ballad-R Piano Ballad Country Ballad On The Road 60's Revival Disco Highlife 70's Ballad Pop Ballad 6-8 Country Beat PianoMan Waltz Club Dance 1 Disco Pop Ballad 12-8 Smooth Ballad Dixie Band Scand Fox Club Dance 2 Euro Club 1 Blues Ballad-R Soft Ballad Dolly Pop Stand By Yours Club Dance 3 Euro Club 2 Folk Singer Sweet 16 Beat Fox Beat Club USA Full House Gentle 16 Beat Uptown 16 More Country Disco Beat Noche Mix Lonely Ballad Nashville Disco Funk For Midjpro • SD Styles / VOL.1 cod.9PDKP5 BALLAD COUNTRY DANCE 8Beat Ballad Lonely Ballad Country Ballad Nashville 60's Revival Disco Highlife 8Beat Ballad-R Piano Ballad Country Beat On The Road Club Dance 1 Euro Club 1 70's Ballad Pop Ballad 6-8 Dixie Band PianoMan Waltz Club Dance 2 Euro Club 2 Ballad 12-8 Smooth Ballad Dolly Pop Scand Fox Club Dance 3 Full House Blues Ballad-R Soft Ballad Fox Beat Stand By Yours Club USA Noche Mix Folk Singer Sweet 16 Beat Francaise Disco Beat Gentle 16 Beat Uptown 16 More Country Disco Funk For SD7 - SD80 • SD Styles / VOL.2 cod.9PDKP2 LATIN PARTY Batucada Gentle Bolero Normal Samba Rumba Flam Boogie Woogie1 Meneito Beguine Les Antilles North Bachata Salsita Boogie Woogie2 Schlager Bossa Argentin Mambo Hit-R Rapido Samba Brazilia Can Can Shue Fox Bossa Brazil Mambo Reggae Drop South Bachata Elvis Boogie Caliente Merenguito-R Reggae Shine Sunny Bossano Flip Beat Cha Cha-R Modern Balada Reggaeton-R Vallenato Flip Fox Cumbia-R Modern Cumbion -

Brazilian Nationalistic Elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2006 Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda Maria Jose Bernardes Di Cavalcanti Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Di Cavalcanti, Maria Jose Bernardes, "Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda" (2006). LSU Major Papers. 39. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/39 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRAZILIAN NATIONALISTIC ELEMENTS IN THE BRASILIANAS OF OSVALDO LACERDA A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti B.M., Universidade Estadual do Ceará (Brazil), 1987 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2002 December 2006 © Copyright 2006 Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This monograph is dedicated to my husband Liduino José Pitombeira de Oliveira, for being my inspiration and for encouraging me during these years -

Tiatr: a New Form of Entrepreneurship in Goa

Communication 33 ISSN 2321 – 371X Tiatr: A New Form of Entrepreneurship Commerce Spectrum 5(2) 33-37 © The Authors 2018 in Goa – Problems and Prospects Reprints and Permissions [email protected] www.commercespectrum.com Dr. Juao C. Costa1 Associate Professor, Department of Commerce,Rosary College of Commerce and Arts, NavelimSalcete Goa. Abstract Tiatr as a form of entrepreneurship has created direct as well as indirect employment to many artists as well as non-performers. Some families are fully dependent on this form of entrepreneurship for their livelihood. The economy of the state to a large extent is supported by this form of entertainment. Realizing its importance in the goan economy, the government of Goa has devised various schemes financial as well as non-financial for the development of tiatr.However, it still needs the attention of the policy makers as it has bright prospects, Goa being a tourist destination.The main objective of the paper would be to highlight how “Tiatr” as a form of entertainment evolved as a form of entrepreneurship providing jobs – directly as well as indirectly to the masses. Key words Tiatr, Tiatrist, culture, entertainment, problem, prospect. Introduction Tiatr1 is a type of musical theatre popular in the GOA, once a Portuguese colony for 450 years, is a state of Goa on the west coast of India as well as in small region on India‟s west coast sandwiched Mumbai and with expatriate communities in the between the Western Ghats and the Arabian Sea Middle East, London and other parts of the world with rich cultural traditions. -

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Peter James Kvetko certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor ______________________________ Gerard Béhague ______________________________ Veit Erlmann ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Herman Van Olphen Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay by Peter James Kvetko, B.A.; M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2005 To Harold Ashenfelter and Amul Desai Preface A crowded, red double-decker bus pulls into the depot and comes to a rest amidst swirling dust and smoke. Its passengers slowly alight and begin to disperse into the muggy evening air. I step down from the bus and look left and right, trying to get my bearings. This is only my second day in Bombay and my first to venture out of the old city center and into the Northern suburbs. I approach a small circle of bus drivers and ticket takers, all clad in loose-fitting brown shirts and pants. They point me in the direction of my destination, the JVPD grounds, and I join the ranks of people marching west along a dusty, narrowing road. Before long, we are met by a colorful procession of drummers and dancers honoring the goddess Durga through thundering music and vigorous dance. The procession is met with little more than a few indifferent glances by tired workers walking home after a long day and grueling commute.