Cruz Da, E. a Study Ofdeknnis. In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2017.Pmd

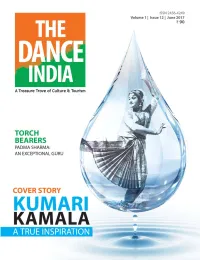

Torch Bearers Padma Sharma: CONTENTSCONTENTS An Exceptional Guru Cover 10 18 Story Rays of Kumari Kamala: 34 Hope A True Inspiration Dr Dwaram Tyagaraj: A Musician with a Big Heart Cultural Beyond RaysBulletin of Hope Borders The Thread of • Expressions34 of Continuity06 Love by Sri Krishna - Viraha Reviews • Jai Ho Russia! Reports • 4th Debadhara 52 Dance Festival • 5 Art Forms under One Roof 58 • 'Bodhisattva' steals the show • Resonating Naatya Tarang • Promoting Unity, Peace and Indian Culture • Tyagaraja's In Sight 250th Jayanthi • Simhapuri Dance Festival: A Celebrations Classical Feast • Odissi Workshop with Guru Debi Basu 42 64 • The Art of Journalistic Writing Tributes Beacons of light Frozen Mandakini Trivedi: -in-Time An Artiste Rooted in 63 Yogic Principles 28 61 ‘The Dance India’- a monthly cultural magazine in "If the art is poor, English is our humble attempt to capture the spirit and culture of art in all its diversity. the nation is sick." Editor-in-Chief International Coordinators BR Vikram Kumar Haimanti Basu, Tennessee Executive Editor Mallika Jayanti, Nebrasaka Paul Spurgeon Nicodemus Associate Editor Coordinators RMK Sharma (News, Advertisements & Subscriptions) Editorial Advisor Sai Venkatesh, Karnataka B Ratan Raju Kashmira Trivedi, Thane Alaknanda, Noida Contributions by Lakshmi Thomas, Chennai Padma Shri Sunil Kothari (Cultural Critic) Parinithi Gopal, Sagar Avinash Pasricha (Photographer) PSB Nambiar Sooryavamsham, Kerala Administration Manager Anurekha Gosh, Kolkata KV Lakshmi GV Chari, New Delhi Dr. Kshithija Barve, Goa and Kolhapur Circulation Manager V Srinivas Technical Advise and Graphic Design Communications Incharge K Bhanuji Rao Articles may be submitted for possible publication in the magazine in the following manner. -

Tabla) I Semester

BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (TABLA) I SEMESTER Course - 101 (English (Spoken)) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To introduce students to the fundamentals of theory and tools of communication. 2. To develop vital communication skills for personal, social and professional interactions. 3. To effectively translate texts. 4. To understand and systematically present facts, idea and opinions. Course Content:- I. Introduction: Theory of Communication, Types and modes of Communication II. Language of Communication: Verbal and Non-verbal (Spoken and Written) Personal, Social and Business, Barriers and Strategies Intra- personal, Inter-personal and Group communication III. Speaking Skills: Monologue, Dialogue, Group Discussion, Effective Communication/ Mis-Communication, Interview, Public Speech. IV. Reading and Understanding: Close Reading, Comprehension, Summary, Paraphrasing, Analysis and Interpretation, Translation(from Indian language to English and Viva-versa), Literary/Knowledge Texts. V. Writing Skills: Documenting, Report Writing, Making notes, Letter writing Bibliographies: a. Fluency in English - Part II, Oxford University Press, 2006. b. Business English, Pearson, 2008. c. Language, Literature and Creativity, Orient Blackswan, 2013. d. Language through Literature (forthcoming) ed. Dr. Gauri Mishra, Dr Ranjana Kaul, Dr Brati Biswas Course - 102 (Hindi) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 मध्यकालीन एवं आधुननक ह ंदी का핍य तथा 핍याकरण Course Objective 1. पाठ्क्रम मᴂ रखी गई कविताओं का गहन अध्ययन करना, उनपर चचाा करना, उनका वििेचन करना, कविताओं का भािार्ा स्पष्ट करना, कविता की भाषा की विशेषताओं तर्ा अर्ा को समझाना। 3. पाठ्क्रम मᴂ रखी गई खण्ड काव्य का गहन अध्ययन कराना,काव्यका भािार्ा स्पष्ट करना, काव्य की भाषा की विशेषताओं तर्ा अर्ा को समझाना। 4. -

Bachelor of Performing Arts (Vocal/Instrumental) I Semester

BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (VOCAL/INSTRUMENTAL) I SEMESTER Course - 101 (English (Spoken)) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To introduce students to the theory, fundamentals and tools of communication. 2. To develop vital communication skills for personal, social and professional interactions. 3. To effectively translate texts. 4. To understand and systematically present facts, idea and opinions. Course Content:- I. Introduction: Theory of Communication, Types and modes of Communication. II. Language of Communication: Verbal and Non-verbal (Spoken and Written) Personal, Social and Business, Barriers and Strategies Intra- personal, Inter-personal and Group communication. III. Speaking Skills: Monologue, Dialogue, Group Discussion, Effective Communication/ Mis-Communication, Interview, Public Speech. IV. Reading and Understanding: Close Reading, Comprehension, Summary, Paraphrasing, Analysis and Interpretation, Translation(from Indian language to English and Viva-versa), Literary/Knowledge Texts. V. Writing Skills: Documenting, Report Writing, Making notes, Letter writing Bibliographies: a. Fluency in English - Part II, Oxford University Press, 2006. b. Business English, Pearson, 2008. c. Language, Literature and Creativity, Orient Blackswan, 2013. d. Language through Literature (forthcoming) ed. Dr. Gauri Mishra, Dr Ranjana Kaul, Dr Brati Biswas Course - 102 (Hindi) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 मध्यकालीन एवं आधुननक ह ंदी काव्य तथा व्याकरण Course Objective:- 1. पाठ्क्रम में रखी गई कनवता䴂 का ग न अध्ययन करना, उनपर चचाा करना, उनका नववेचन करना, कनवता䴂 का भावाथा स्पष्ट करना, कनवता की भाषा की नवशेषता䴂 तथा अथा को समझाना। 2. पाठ्क्रम में रखी गई खण्ड काव्य का ग न अध्ययन कराना,काव्यका भावाथा स्पष्ट करना, काव्य की भाषा की नवशेषता䴂 तथा अथा को समझाना। 3. -

Goa College of Music

GOVERNMENT OF GOA GOA COLLEGE OF MUSIC (AFFILIATED TO GOA UNIVERSITY) ALTINHO, PANAJI-GOA Phone No.: 2232507/2432528 Email: [email protected] PROSPECTUS & SYLLABUS OF MASTER OF PERFORMING ARTS (M.P.A.) GOA COLLEGE OF MUSIC ALTINHO,PANAJI-GOA PROSPECTUS OF POST GRADUATE DEGREE COURSE- MASTER OF PERFORMING ARTS IN HINDUSTANI CLASSICAL MUSIC INTRODUCTION : Goa College of Music, a Govt. College affiliated to Goa University was founded on 1.8.1987. The College is conducting two years Foundation Course and four years degree course leading to Bachelor of Performing Arts in Hindustani Classical Music. Besides, the College is also conducting the Post Graduate Degree Course in Vocal Music leading to Master of Performing Arts. The basic aim of the Courses is to impart the full time professional training in Hindustani Classical Vocal Music and Instrumental Music such as Harmonium, Sitar and Tabla/Pakhawaj etc. It is aimed to provide a specialized training to the Music students in all important aspects of Hindustani Music with a special emphasis on developing his/her performing ability to the professional standard. The College is also conducting part time Diploma Courses in Vocal, Harmonium and Tabla for the general students and music lovers. THE NATURE OF EDUCATION : A student is given manifold training covering the following areas : 1. Actual training in singing ragas, with an accent on proper application of voice, tunefulness and developing mastery of rhythm. In the case of instrumental music, proper technique in playing the instrument is taught and training is given in various Ragas and Talas. 2. The training will be more practical oriented and more stress will be given on the performing part of the students with the aim of attaining the professional standard by the students. -

Background Material on Service Tax- Entertainment Sector

Background Material on Service Tax- Entertainment Sector The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (Set up by an Act of Parliament) New Delhi © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission, in writing, from the publisher. DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this book are of the author(s). The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India may not necessarily subscribe to the views expressed by the author(s). The information cited in this book has been drawn from various sources. While every effort has been made to keep the information cited in this book error free, the Institute or any office of the same does not take the responsibility for any typographical or clerical error which may have crept in while compiling the information provided in this book. Edition : February, 2015 Committee/Department : Indirect Taxes Committee Email : [email protected] Website : www.idtc.icai.org Price : ` 90/- ISBN No. : 978-81-8441-759-3 Published by : The Publication Department on behalf of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, ICAI Bhawan, Post Box No. 7100, Indraprastha Marg, New Delhi - 110 002. Printed by : Sahitya Bhawan Publications, Hospital Road, Agra 282 003 February/2015/1,000 Foreword The introduction of Service Tax was recommended by Dr. Raja Chelliah Committee in early 1990s which pointed out that the indirect taxes at the Central level should be broadly neutral in relation to production and consumption of goods and should, in course of time cover commodities and services. -

Religious Dances and Tourism: Perceptions of the “Tribal”

Etnográfica Revista do Centro em Rede de Investigação em Antropologia vol. 21 (1) | 2017 Inclui dossiê "India’s other sites: representations at home and abroad" Religious dances and tourism: perceptions of the “tribal” as the repository of the traditional in Goa, India Danças religiosas e turismo: os “tribais” percecionados como o repositório do tradicional em Goa, Índia Cláudia Pereira Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etnografica/4850 DOI: 10.4000/etnografica.4850 ISSN: 2182-2891 Publisher Centro em Rede de Investigação em Antropologia Printed version Date of publication: 1 February 2017 Number of pages: 125-152 ISSN: 0873-6561 Electronic reference Cláudia Pereira, « Religious dances and tourism: perceptions of the “tribal” as the repository of the traditional in Goa, India », Etnográfica [Online], vol. 21 (1) | 2017, Online since 11 March 2017, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etnografica/4850 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.4850 Etnográfica is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. etnográfica fevereiro de 2017 21 (1): 125-152 Religious dances and tourism: perceptions of the “tribal” as the repository of the traditional in Goa, India Cláudia Pereira What changes occur in the identity of a group considered tribal in India through the performance of their dances? What is the influence of tourism on their religious cults? How are they perceived by other Indians? To answer these questions, first I analyze how the Goan government sought to institutionalize these tribal dances. Second, I examine the gains in the group’s political, economic and cultural capital through this transition to the tourism industry. -

The Organs of Goa, India

The Organs of Goa, India Paper delivered by David Rumsey Conference in Mafra, Portugal, December 1994 In considering the broader aspects of Portugal's organ culture, in particular the activities of the navigators and those who followed them, we need to ask whether the export of organs was ever a significant part of her colonisation processes. We may think of South America or even the Philippines in this connection, where Spain left such obvious and well-known musical testaments to her wealth and religious culture. We may also think of geographically-transferred organ cultures, through colonialism, that have even helped in the preservation of some organ types - for example Victorian English organs now preserved in Australia. Portugal was present in South America, Africa, and had important smaller colonies, among them, Macao, Timor, Goa, Daman and Diu. To begin to answer this question it is therefore relevant to investigate the number, kind, and condition of surviving organs in Goa and whether Portuguese instruments ever existed there. We may also find some secondary clues through observing the region's existing church music culture. Goa is situated 250 Km south of Bombay in India. It is about 60 Km North to South and 30 Km East to West, mostly flat country, broken mainly by two major river systems: the Mandovi and the Zuari. Panajim is the capital city1. Indian and Portuguese food, music and language are now generally blended in a culture designated as "Konkani". Other traditions coexist, for example Hindu music is taught to high standards at the Swami Vivekananda music school in Panajim2. -

Goa Art & Culture

Goa Art & Culture Goa, a former Portuguese territory, for more than 450 years is often described as 'The Rome of the East'. It has over the past decades, become the dream holiday destination, for many a foreign tourist. Goa's rich cultural heritage comprises of dances, folk songs, visual arts, music and folk tales rich in content and variety. Goan are born music lovers, most Goans can pluck at a guitar or pick out a tune on the piano. Music is in the blood of Goans since time immemorial, in almost every family you would find a pianist or a guitarist. Being a part of the culture, music of Goa is a blend of east and west. While the rural areas still stick to the traditional forms of music, the urban areas have shifted to a more modern version. You would get every music from Portuguese to Techno and rave, but what has caught Goa these days is the Goa Trance. Goa Trance is a vibrant and psychedelic dance music that is best enjoyed on the dance drug LSD and is a powerful and kaleidoscopic tapestry of sound. Of late Goa Trance has also made an impact in the international music circles. The music is so much in demand in parties that they are now called the trance parties. The almost forgotten folk dances Dhalo, Fugdi, Corridinho, Mando and performing folk arts (like Khell-Tiatro), Jagar-perani and many others have come out into their own. Indeed the folk music and folk dances have crossed the borders of the state and become popular in the rest of the country during the past 25 years. -

Desai, SS 1988. an Ethnological Study of Goan

Desai, S. S. 1988. An ethnological Study of Goan Society. In: Shirodkar, P. P., Goa: Cultural Trends. Pp. 34-45. Directorate of Archives, Archaeology and Museum, Govt. of Goa, Panaji, Goa. 34 An ethnological study of Goan society - S. S. Desai At the outset i~ needs to be emphasized that the meaning of the word culture is broad. It is connected with civilization, but not in wide sense. It is a modern word and derived from German word Kultur. It became popular in the beginning of this century. Culture is a way of life and it covers all facets of human life, such as anthropology, ethnology, history language, literature, costumes, habits, tr.aditions, etc. In this context, it is worth discussing some aspects of Goan traditions and life. Dr. Antonio de Bragan·~a Pereira, a jurist and researcher in history has to his credit a book under the title 'Ethnografia da India Portuguesa' in two volumes. Though it is written in Portuguese, it has immense historical value. In the second volume of this book, Dr.Braganca Pereira has dealt with ·extensively the history of the castes and communities ill Goa. He says that there are 30 to 35 castes and sub-castes among Hindus of Goa,• 17 amongst the Catholics and 20 amongst Muslims. In comparison with the castes and communities in Maharashtra and Kamataka, the neighbouring States of Goa, the majority of castes and communities in Maharashtra are to be found in Goa. But, where did tt1ey come from? Certainly they might have migrated to Goa from Maharashtra. The students of ancient history oflndia are well aware that in bygone days Goa formed a part of the province of Aparant. -

JPG to PDF When the Curtains Rise

generated by JPG to PDF www.jpgtopdfconverter.net When the curtains rise... Understanding Goa’s vibrant Konkani theatre André Rafael Fernandes, Ph.D. When the curtains rise... Understanding Goa’s vibrant Konkani theatre © André Rafael Fernandes [email protected] or [email protected] Ph +91-9823385638 Published with financial support from the Tiatr Academy of Goa (TAG) S-4, Block A, 2nd Floor, Campal Trade Centre, Opp. Kala Academy, Campal, Panjim 403001 Goa [email protected] Editing, inside-pages layout and book production by Frederick Noronha Goa,1556, 784 Sãligao, 403511 Goa. Ph +91-832-2409490 http://goa1556.goa-india.org Cover design by Bina Nayak http://www.binanayak.com Printed in India by Sahyadri Offset Systems, Corlim, Ilhas, Goa Typeset with LYX, http://www.lyx.org Text set in Palatino, 11 pt. Creative Commons 3.0, non-commercial, attribution. May be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, with attribution. ISBN 978-93-80739-01-4 Front cover illustration depicts a handbill for the 1904 performance of Batcara. List of characters confirms the early participation of women in the tiatr, at a time when this was not prevalent in other Indian theatre forms. Also on front cover, a handbill of Batcara, staged in 1915 for the Women’s War Relief Fund in World War I days. Back cover shows a partial facsimile of a book by Pai Tiatrist João Agostinho Fernandes. Price: Rs. 195 in India. CÓÒØeÒØ× 1 Originofthetiatr 1 Indigenous traditions: Goa’s folk performances . 8 Tiatr’sprecedents . 12 Folk art forms of Christians in Goa . 19 2 Legacyof music, song 25 Indian classical music: Hindustani, Karnatak . -

Mascarenhas, Mira. 1988. Impact of the West on Go

Mascarenhas, Mira. 1988. Impact of the West on Go an Music. In: Shirodkar, P. P., Goa: Cultural Trends. Pp. 189-204. Directorate of Archives, Archaeology and Museum, Govt. of Goa, Panaji, Goa. 189 Impact of the West on Goan music -Mira Mascarenhas Being on the west coast of India, and ideally situated on the shipping lanes of the ancient world, Goa h<:!l always been open to the Western influences coming to it across the Indian Ocean. The old Konkan legendl imputing Chitpavan Brahmin origin to Arab seamen, even if historically unprovable, points to a considerable infusion of ethnic and cultural elements into the primitive populations of the Konkan. How far this affected the ancient music of Goa has necessarily to remain a matter of conjecture, since·we have no records on the subject. · Goan music, as we know it today, can be divided broadly into two bodies, according to the usage of ~he two major Goan communities, Hindu and Christian. Tlie first is at least ten · ·centuries old, and is foremost among the musical traditions of the Konkan2· -It is solidly based on the Indian classical moulds, namely those which developed from Vedic beginning. When, however, we speak of the '-iiJlpact of the West,' we immediately think of the second body of Goan music, i.e, that which is sung, played or danced to by the Christians and which is not more than 459 years old. The early history of this music is certainly,.bound up with the history of conversion to Christianity after the Portuguese con<iuest of Goa and the m~3ic of the .church has played a decisive pan in shaping tmd Influencing it. -

Irvine, California July 1-3, 2000 4� &Irk Rtitf Cfrutql

Irvine, California July 1-3, 2000 4 &irk rtitf CfRUTql Alt9twrtRIRRqT17 g pint tr4311- -4 TrzTFTVI-A. 'Errk;• 71Tf TIT 7117gra' Tra:r, t Tiqf Trr6t. tIta4t, ftc4.44f AltiltrqT ilt;T:RwcT xgr R.r7-41-4T .#r ErtT qtr, 117R tt CWT, w-Err w-qtr 3r0;Atrqr TwIt tgattr, 7arqr A.gr If t'44 :41n-aq-crq WEliziTWizkitTrait 3Tita' 9 1 Vcr 31t, 31# ti*CTEI, Rzft 3I# 7Tfilimtrkt T.M. 1R--41.4)44d4ci), ttf Atrt-otrrit -49-47qtr-qr 41. Convention Center, Irvine Hilton, 18800 McArthur Boulevard Irvine, California 92614 Saturday, July 1, 2000 Dear Friends, Two years ago in Orlando, I volunteered to host our 5th biannual Goan Organization in America Convention in the Golden State of California. After two long years, the time has finally arrived. Welcome to the wonderful City of Irvine in sunny southern California! Sharing the enthusiasm and support of us Goans in California, I am delighted to have you with us in Irvine for this marvelous event to bring in the new Millennium. Your Convention Organizing Committee has put together an exciting and fun-filled program for you to enjoy and relax with your family and friends. At the convention, you will meet old friends and catch up on the each other's progress. You will also meet attendees from elsewhere in North America and around the world, including Goa, that share your same Goan heritage and hopefully many lasting friendships can be made at Goan Convention 2000. This interaction is a major accomplishment, which fulfills a mission for most of us who call Goa "home".