José Pereira

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

A Commercial Study of TIATR As a Form of Entertainment in Goa (India

A Commercial Study of TIATR as a form of Entertainment in Goa (India): An Empirical Analysis Dr.Juao Costa Associate Professor, Rosary College of Commerce and Arts, Navelim, Salcete, Goa. 403707. Abstract: Introduction: The state of Goa is rich in culture; heritage and art The state of Goa is rich in culture; heritage and art especially performing art in Goa is a unique feature of especially performing art in Goa is a unique feature of the state. Though all these forms fall under the wide the state. Though all these forms fall under the wide classification of dance, dramas and music yet the classification of dance, dramas and music yet the dance in Goa has a distinct Goan flavour and can be dance in Goa has a distinct Goan flavour and can be easily be distinguished from those of the other states. easily be distinguished from those of the other states. The most significant part about the performing arts in The most significant part about the performing arts in Goa is the fact that each of them colorfully illustrates Goa is the fact that each of them colourfully illustrates the unity in diversity of Goan heritage. Goan rich the unity in diversity of Goan heritage. Goan rich cultural heritage comprises of dance, folksongs, music cultural heritage comprises of dance, folksongs, music and folk tales rich in the content and variety. Goans are and folk tales rich in the content and variety. Goans are born music lovers. Goans are very fond of theatre and born music lovers. Goans are very fond of theatre and acting. -

Folk Theatre in Goa: a Critical Study of Select Forms Thesis

FOLK THEATRE IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECT FORMS THESIS Submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY For the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar Under the Guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K. J. Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. January 2018 CERTIFICATE As required under the University Ordinance, OA-19.8 (viii), I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, submitted by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English has been completed under my guidance. The thesis is the record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to her by this or any other University. Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. Date: i DECLARATION As required under the University Ordinance OA-19.8 (v), I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley, Professor of English (Retd.),Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in the thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to me, by this or any other University. Ms. -

Goa University Glimpses of the 22Nd Annual Convocation 24-11-2009

XXVTH ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 asaicT ioo%-io%o GOA UNIVERSITY GLIMPSES OF THE 22ND ANNUAL CONVOCATION 24-11-2009 Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon ble President of India, arrives at Hon'ble President of India, with Dr. S. S. Sidhu, Governor of Goa the Convocation venue. & Chancellor, Goa University, Shri D. V. Kamat, Chief Minister of Goa, and members of the Executive Council of Goa University. Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon'ble President of India, A section of the audience. addresses the Convocation. GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 XXV ANNUAL REPORT June 2009- May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 CONTENTS Pg, No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3; ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY FACULTY INTRODUCTION 5 A: Seminars Organised 58 PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1.1 Members of Executive Council 6 C; ' Research Publications 72 D: Articles in Books 78 1.2 Members of University Court 6 E: Book Reviews 80 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ Conduct of Examinations 85 CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Library 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Sports 87 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Directorate of Students’ Welfare & 88 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. -

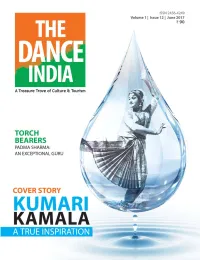

June 2017.Pmd

Torch Bearers Padma Sharma: CONTENTSCONTENTS An Exceptional Guru Cover 10 18 Story Rays of Kumari Kamala: 34 Hope A True Inspiration Dr Dwaram Tyagaraj: A Musician with a Big Heart Cultural Beyond RaysBulletin of Hope Borders The Thread of • Expressions34 of Continuity06 Love by Sri Krishna - Viraha Reviews • Jai Ho Russia! Reports • 4th Debadhara 52 Dance Festival • 5 Art Forms under One Roof 58 • 'Bodhisattva' steals the show • Resonating Naatya Tarang • Promoting Unity, Peace and Indian Culture • Tyagaraja's In Sight 250th Jayanthi • Simhapuri Dance Festival: A Celebrations Classical Feast • Odissi Workshop with Guru Debi Basu 42 64 • The Art of Journalistic Writing Tributes Beacons of light Frozen Mandakini Trivedi: -in-Time An Artiste Rooted in 63 Yogic Principles 28 61 ‘The Dance India’- a monthly cultural magazine in "If the art is poor, English is our humble attempt to capture the spirit and culture of art in all its diversity. the nation is sick." Editor-in-Chief International Coordinators BR Vikram Kumar Haimanti Basu, Tennessee Executive Editor Mallika Jayanti, Nebrasaka Paul Spurgeon Nicodemus Associate Editor Coordinators RMK Sharma (News, Advertisements & Subscriptions) Editorial Advisor Sai Venkatesh, Karnataka B Ratan Raju Kashmira Trivedi, Thane Alaknanda, Noida Contributions by Lakshmi Thomas, Chennai Padma Shri Sunil Kothari (Cultural Critic) Parinithi Gopal, Sagar Avinash Pasricha (Photographer) PSB Nambiar Sooryavamsham, Kerala Administration Manager Anurekha Gosh, Kolkata KV Lakshmi GV Chari, New Delhi Dr. Kshithija Barve, Goa and Kolhapur Circulation Manager V Srinivas Technical Advise and Graphic Design Communications Incharge K Bhanuji Rao Articles may be submitted for possible publication in the magazine in the following manner. -

CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. Introduction 1 2. Functions of the Directorate Of

I N D E X CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. Introduction 1 2. Functions of the Directorate of Official Language 2 3. Steps initiated to implement the Official Language Act 3 – 4 4. Analysis & Recommendations 5 5. Plan Schemes 6 – 9 - 1 - 1. Introduction : In accordance with the Government of Goa, the Directorate of Official Language was established in 2004 as an independent Department of Government of Goa and entrusted with the nodal responsibility for all matters relating to the progressive use of Konkani as the Official Language of the State of Goa. As per the Government the Directorate adopted Konkani as the Official Language of the then Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu and accordingly the Goa, Daman and Diu Official Language Act 1987 (Act 5 of 1987) was enacted in pursuance of Section 34 of the Government of Union Territories Act, 1963 (Central Act 20 of 1963), Official Language Act 1987 which provides Konkani shall be the Official Language whereas, Marathi shall be used for all or any of the Official purposes. The Act envisaged the continuance of the English language of for official purposes in addition to Konkani & Marathi languages. - 2 - 2. Functions of the Directorate of Official Language : Its main functions include, inter-alia, the following : i. Enhancing the efficacy of Official language the Department releases recurring grants in aid to Goa Konkani Akademi. The Goa Konkani Akademi was established by the Government of Goa in the year 1984. ii. Recurring Grants in aid to Gomantak Marathi Academy for promoting Marathi language. The Gomantak Marathi Academy is an autonomous, sovereign Institution and was registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, bearing registration No. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities Thesis Submitted to Goa University For the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English by Ms. Leanora Madeira née Pereira Under the Guidance of Prof. Nina Caldeira Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 August, 2020 CERTIFICATE I hereby certify that the thesis entitled “Identitarian Spaces of Goan Diasporic Communities” submitted by Ms. Leanora Pereira for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, has been completed under my supervision. The thesis is a record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other University. Prof. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. ii Declaration As required under the Ordinance OB 9A.9(v), I hereby declare that this thesis titled Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Professor Dr. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in this thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or any other titles awarded to me by this or any other university. Ms. Leanora Pereira Madeira Research Student Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 Date: August 2020 iii Acknowledgement The path God creates for each one of us is unique. I bow my head to the Almighty acknowledging him as the Alpha and the Omega and Lord of the Universe. -

Tiatr: a New Form of Entrepreneurship in Goa

Communication 33 ISSN 2321 – 371X Tiatr: A New Form of Entrepreneurship Commerce Spectrum 5(2) 33-37 © The Authors 2018 in Goa – Problems and Prospects Reprints and Permissions [email protected] www.commercespectrum.com Dr. Juao C. Costa1 Associate Professor, Department of Commerce,Rosary College of Commerce and Arts, NavelimSalcete Goa. Abstract Tiatr as a form of entrepreneurship has created direct as well as indirect employment to many artists as well as non-performers. Some families are fully dependent on this form of entrepreneurship for their livelihood. The economy of the state to a large extent is supported by this form of entertainment. Realizing its importance in the goan economy, the government of Goa has devised various schemes financial as well as non-financial for the development of tiatr.However, it still needs the attention of the policy makers as it has bright prospects, Goa being a tourist destination.The main objective of the paper would be to highlight how “Tiatr” as a form of entertainment evolved as a form of entrepreneurship providing jobs – directly as well as indirectly to the masses. Key words Tiatr, Tiatrist, culture, entertainment, problem, prospect. Introduction Tiatr1 is a type of musical theatre popular in the GOA, once a Portuguese colony for 450 years, is a state of Goa on the west coast of India as well as in small region on India‟s west coast sandwiched Mumbai and with expatriate communities in the between the Western Ghats and the Arabian Sea Middle East, London and other parts of the world with rich cultural traditions. -

Tabla) I Semester

BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (TABLA) I SEMESTER Course - 101 (English (Spoken)) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To introduce students to the fundamentals of theory and tools of communication. 2. To develop vital communication skills for personal, social and professional interactions. 3. To effectively translate texts. 4. To understand and systematically present facts, idea and opinions. Course Content:- I. Introduction: Theory of Communication, Types and modes of Communication II. Language of Communication: Verbal and Non-verbal (Spoken and Written) Personal, Social and Business, Barriers and Strategies Intra- personal, Inter-personal and Group communication III. Speaking Skills: Monologue, Dialogue, Group Discussion, Effective Communication/ Mis-Communication, Interview, Public Speech. IV. Reading and Understanding: Close Reading, Comprehension, Summary, Paraphrasing, Analysis and Interpretation, Translation(from Indian language to English and Viva-versa), Literary/Knowledge Texts. V. Writing Skills: Documenting, Report Writing, Making notes, Letter writing Bibliographies: a. Fluency in English - Part II, Oxford University Press, 2006. b. Business English, Pearson, 2008. c. Language, Literature and Creativity, Orient Blackswan, 2013. d. Language through Literature (forthcoming) ed. Dr. Gauri Mishra, Dr Ranjana Kaul, Dr Brati Biswas Course - 102 (Hindi) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 मध्यकालीन एवं आधुननक ह ंदी का핍य तथा 핍याकरण Course Objective 1. पाठ्क्रम मᴂ रखी गई कविताओं का गहन अध्ययन करना, उनपर चचाा करना, उनका वििेचन करना, कविताओं का भािार्ा स्पष्ट करना, कविता की भाषा की विशेषताओं तर्ा अर्ा को समझाना। 3. पाठ्क्रम मᴂ रखी गई खण्ड काव्य का गहन अध्ययन कराना,काव्यका भािार्ा स्पष्ट करना, काव्य की भाषा की विशेषताओं तर्ा अर्ा को समझाना। 4. -

S Goesas Em Konkani Songs From

GOENCHIM KONKNI GAIONAM 1 CANÇO?S GOESAS EM KONKANI2 SONGS FROM GOA IN KONKANI 1 Konkani 2 Portuguese 1 Goans spoke Portuguese but sang in Konkani, a language brought to Goa by the Indian Arya. + A Goan way of expressing love: “Xiuntim mogrim ghe rê tuka, Sukh ani sontos dhi rê maka.” These Chrysanthemum and Jasmine flowers I give to thee, Joy and happiness give thou to me. 2 Bibliography3 A selection as background information Refer to Pereira, José / Martins, Micael. “Goa and its Music”, in: UUUUBoletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Nr.155 (1988) pp. 41-72 (Bibliography 43-55) for an extensive selection and to the Mando Festival Programmes published by the Konkani Bhasha Mandal in Panaji for recent compositions. Almeida, Mathew . 1988. Konkani Orthography. Panaji: Dalgado Konknni Akademi. Barreto, Lourdinho. 1984. Goemchem Git. Pustok 1 and 2. Panaji: Pedro Barreto, Printer. Barros de, Joseph. 1989. “The first Book to be printed in India”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 159. pp. 5-16. Barros de, Joseph. 1993. “The Clergy and the Revolt in Portuguese Goa”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 169. pp. 21-37. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). 2000. Goa and Portugal. History and Development. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). Goa´s formost Nationalist: José Inácio Candido de Loyola. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. (Loyola is mentioned in the mando Setembrachê Ekvissavêru). Bragança, Alfred. 1964. “Song and Music”, in: The Discovery of Goa. Panaji: Casa J.D. Fernandes. pp. 41-53. Coelho, Victor A. -

Bachelor of Performing Arts (Vocal/Instrumental) I Semester

BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (VOCAL/INSTRUMENTAL) I SEMESTER Course - 101 (English (Spoken)) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To introduce students to the theory, fundamentals and tools of communication. 2. To develop vital communication skills for personal, social and professional interactions. 3. To effectively translate texts. 4. To understand and systematically present facts, idea and opinions. Course Content:- I. Introduction: Theory of Communication, Types and modes of Communication. II. Language of Communication: Verbal and Non-verbal (Spoken and Written) Personal, Social and Business, Barriers and Strategies Intra- personal, Inter-personal and Group communication. III. Speaking Skills: Monologue, Dialogue, Group Discussion, Effective Communication/ Mis-Communication, Interview, Public Speech. IV. Reading and Understanding: Close Reading, Comprehension, Summary, Paraphrasing, Analysis and Interpretation, Translation(from Indian language to English and Viva-versa), Literary/Knowledge Texts. V. Writing Skills: Documenting, Report Writing, Making notes, Letter writing Bibliographies: a. Fluency in English - Part II, Oxford University Press, 2006. b. Business English, Pearson, 2008. c. Language, Literature and Creativity, Orient Blackswan, 2013. d. Language through Literature (forthcoming) ed. Dr. Gauri Mishra, Dr Ranjana Kaul, Dr Brati Biswas Course - 102 (Hindi) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 मध्यकालीन एवं आधुननक ह ंदी काव्य तथा व्याकरण Course Objective:- 1. पाठ्क्रम में रखी गई कनवता䴂 का ग न अध्ययन करना, उनपर चचाा करना, उनका नववेचन करना, कनवता䴂 का भावाथा स्पष्ट करना, कनवता की भाषा की नवशेषता䴂 तथा अथा को समझाना। 2. पाठ्क्रम में रखी गई खण्ड काव्य का ग न अध्ययन कराना,काव्यका भावाथा स्पष्ट करना, काव्य की भाषा की नवशेषता䴂 तथा अथा को समझाना। 3.