Kale, Pramod. 1999. Tiatr. Expression of the Live

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Commercial Study of TIATR As a Form of Entertainment in Goa (India

A Commercial Study of TIATR as a form of Entertainment in Goa (India): An Empirical Analysis Dr.Juao Costa Associate Professor, Rosary College of Commerce and Arts, Navelim, Salcete, Goa. 403707. Abstract: Introduction: The state of Goa is rich in culture; heritage and art The state of Goa is rich in culture; heritage and art especially performing art in Goa is a unique feature of especially performing art in Goa is a unique feature of the state. Though all these forms fall under the wide the state. Though all these forms fall under the wide classification of dance, dramas and music yet the classification of dance, dramas and music yet the dance in Goa has a distinct Goan flavour and can be dance in Goa has a distinct Goan flavour and can be easily be distinguished from those of the other states. easily be distinguished from those of the other states. The most significant part about the performing arts in The most significant part about the performing arts in Goa is the fact that each of them colorfully illustrates Goa is the fact that each of them colourfully illustrates the unity in diversity of Goan heritage. Goan rich the unity in diversity of Goan heritage. Goan rich cultural heritage comprises of dance, folksongs, music cultural heritage comprises of dance, folksongs, music and folk tales rich in the content and variety. Goans are and folk tales rich in the content and variety. Goans are born music lovers. Goans are very fond of theatre and born music lovers. Goans are very fond of theatre and acting. -

If Goa Is Your Land, Which Are Your Stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home*

If Goa is your land, which are your stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home* Cielo Griselda Festinoa Abstract Goa, India, is a multicultural community with a broad archive of literary narratives in Konkani, Marathi, English and Portuguese. While Konkani in its Devanagari version, and not in the Roman script, has been Goa’s official language since 1987, there are many other narratives in Marathi, the neighbor state of Maharashtra, in Portuguese, legacy of the Portuguese presence in Goa since 1510 to 1961, and English, result of the British colonization of India until 1947. This situation already reveals that there is a relationship among these languages and cultures that at times is highly conflictive at a political, cultural and historical level. In turn, they are not separate units but are profoundly interrelated in the sense that histories told in one language are complemented or contested when narrated in the other languages of Goa. One way to relate them in a meaningful dialogue is through a common metaphor that, at one level, will help us expand our knowledge of the points in common and cultural and * This paper was carried out as part of literary differences among them all. In this article, the common the FAPESP thematic metaphor to better visualize the complex literary tradition from project "Pensando Goa" (proc. 2014/15657-8). The Goa will be that of the village since it is central to the social opinions, hypotheses structure not only of Goa but of India. Therefore, it is always and conclusions or recommendations present in the many Goan literary narratives in the different expressed herein are languages though from perspectives that both complement my sole responsibility and do not necessarily and contradict each other. -

Folk Theatre in Goa: a Critical Study of Select Forms Thesis

FOLK THEATRE IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECT FORMS THESIS Submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY For the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar Under the Guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K. J. Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. January 2018 CERTIFICATE As required under the University Ordinance, OA-19.8 (viii), I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, submitted by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English has been completed under my guidance. The thesis is the record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to her by this or any other University. Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. Date: i DECLARATION As required under the University Ordinance OA-19.8 (v), I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley, Professor of English (Retd.),Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in the thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to me, by this or any other University. Ms. -

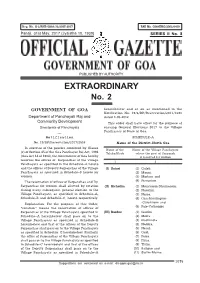

Sr. II N O. 8 Ext. 2.Pmd

Reg. No. G-2/RNP/GOA/32/2015-2017 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 31st May, 2017 (Jyaistha 10, 1939) SERIES II No. 8 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY EXTRAORDINARY No. 2 GOVERNMENT OF GOA hereinbelow and so on as mentioned in the Notification No. 19/6/DP/Reservation/2011/1698 Department of Panchayati Raj and dated 8-05-2012. Community Development This order shall have effect for the purpose of Directorate of Panchayats ensuing General Elections 2017 to the Village __ Panchayats of State of Goa. Notification SCHEDULE–A No. 19/DP/Reservation/2017/2558 Name of the District–North Goa In exercise of the powers conferred by Clause Name of the Name of the Village Panchayats (c) of Section 45 of the Goa Panchayat Raj Act, 1994 Taluka/Block where the post of Sarpanch (Goa Act 14 of 1994), the Government of Goa hereby is reserved for women reserves the offices of Sarpanchas of the Village 12 Panchayats as specified in the Schedule–A hereto and the offices of Deputy Sarpanchas of the Village (I) Satari (1) Guleli. Panchayats as specified in Schedule–B hereto for (2) Mauxi. women. (3) Morlem and The reservation of offices of Sarpanchas and Dy. (4) Pissurlem. Sarpanchas for women shall allotted by rotation (II) Bicholim (1) Mencurem-Dhumacem. during every subsequent general election to the (2) Navelim. Village Panchayats, as specified in Schedule–A, (3) Naroa. Schedule–B and Schedule–C, hereto respectively. (4) Ona-Maulingem- -Curchirem and Explanation: For the purpose of this Order, (5) Pale-Cothombi. “rotation” means the reservation of offices of Sarpanchas of the Village Panchayats specified in (III) Bardez (1) Guirim. -

Goa University Glimpses of the 22Nd Annual Convocation 24-11-2009

XXVTH ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 asaicT ioo%-io%o GOA UNIVERSITY GLIMPSES OF THE 22ND ANNUAL CONVOCATION 24-11-2009 Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon ble President of India, arrives at Hon'ble President of India, with Dr. S. S. Sidhu, Governor of Goa the Convocation venue. & Chancellor, Goa University, Shri D. V. Kamat, Chief Minister of Goa, and members of the Executive Council of Goa University. Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon'ble President of India, A section of the audience. addresses the Convocation. GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 XXV ANNUAL REPORT June 2009- May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 CONTENTS Pg, No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3; ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY FACULTY INTRODUCTION 5 A: Seminars Organised 58 PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1.1 Members of Executive Council 6 C; ' Research Publications 72 D: Articles in Books 78 1.2 Members of University Court 6 E: Book Reviews 80 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ Conduct of Examinations 85 CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Library 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Sports 87 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Directorate of Students’ Welfare & 88 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

Wonderful Goa - Golden sun, white sands and local cuisines The programme Come to Goa to unwind on its white sand beaches, simply relax and soak in the sun while tasting some bites of the delicious Goan cuisine and seafood. Don’t miss Old Goa with its stunning cathedrals and architecture that witness the glorious Portuguese past of Goa. The Experiences Explore the white sand beaches of Goa Enjoy water sports like boating, parasailing, banana rides and Jet Ski Explore the famous nightclubs of Goa Visit Dudhsagar waterfalls Tour the churches of Goa Discover Loutolim, an old town where Hindus and Christians live in harmony Visit the flea markets of Goa Wonderful Goa - Golden sun, white sands and local cuisines The Experiences | Day 01: Arrive Goa Welcome to India! On arrival at Goa Airport, you will be greeted by our tour representative in the arrival hall, who will escort you to your hotel and assist you in check-in. Kick off your holiday unwinding on the golden sand beaches of Goa. Laze around at Calangute Beach and Candolim Beach and enjoy the delightful Goan cuisine. Goa is famous for its seafood, including deliciously cooked crabs, prawns, squids, lobsters and oysters. The influence of Portuguese on Indian cuisine can best be explored here. As an ex-colony, Goa still retains Portuguese influences even today. Soak up the sunset panorama at Baga Beach - a crowded beach that comes to life at twilight. Spend a few hours by candle light and enjoy drinks and dinner with the sound of gushing waves in the background. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities Thesis Submitted to Goa University For the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English by Ms. Leanora Madeira née Pereira Under the Guidance of Prof. Nina Caldeira Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 August, 2020 CERTIFICATE I hereby certify that the thesis entitled “Identitarian Spaces of Goan Diasporic Communities” submitted by Ms. Leanora Pereira for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, has been completed under my supervision. The thesis is a record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other University. Prof. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. ii Declaration As required under the Ordinance OB 9A.9(v), I hereby declare that this thesis titled Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Professor Dr. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in this thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or any other titles awarded to me by this or any other university. Ms. Leanora Pereira Madeira Research Student Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 Date: August 2020 iii Acknowledgement The path God creates for each one of us is unique. I bow my head to the Almighty acknowledging him as the Alpha and the Omega and Lord of the Universe. -

Tiatr: a New Form of Entrepreneurship in Goa

Communication 33 ISSN 2321 – 371X Tiatr: A New Form of Entrepreneurship Commerce Spectrum 5(2) 33-37 © The Authors 2018 in Goa – Problems and Prospects Reprints and Permissions [email protected] www.commercespectrum.com Dr. Juao C. Costa1 Associate Professor, Department of Commerce,Rosary College of Commerce and Arts, NavelimSalcete Goa. Abstract Tiatr as a form of entrepreneurship has created direct as well as indirect employment to many artists as well as non-performers. Some families are fully dependent on this form of entrepreneurship for their livelihood. The economy of the state to a large extent is supported by this form of entertainment. Realizing its importance in the goan economy, the government of Goa has devised various schemes financial as well as non-financial for the development of tiatr.However, it still needs the attention of the policy makers as it has bright prospects, Goa being a tourist destination.The main objective of the paper would be to highlight how “Tiatr” as a form of entertainment evolved as a form of entrepreneurship providing jobs – directly as well as indirectly to the masses. Key words Tiatr, Tiatrist, culture, entertainment, problem, prospect. Introduction Tiatr1 is a type of musical theatre popular in the GOA, once a Portuguese colony for 450 years, is a state of Goa on the west coast of India as well as in small region on India‟s west coast sandwiched Mumbai and with expatriate communities in the between the Western Ghats and the Arabian Sea Middle East, London and other parts of the world with rich cultural traditions. -

S Goesas Em Konkani Songs From

GOENCHIM KONKNI GAIONAM 1 CANÇO?S GOESAS EM KONKANI2 SONGS FROM GOA IN KONKANI 1 Konkani 2 Portuguese 1 Goans spoke Portuguese but sang in Konkani, a language brought to Goa by the Indian Arya. + A Goan way of expressing love: “Xiuntim mogrim ghe rê tuka, Sukh ani sontos dhi rê maka.” These Chrysanthemum and Jasmine flowers I give to thee, Joy and happiness give thou to me. 2 Bibliography3 A selection as background information Refer to Pereira, José / Martins, Micael. “Goa and its Music”, in: UUUUBoletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Nr.155 (1988) pp. 41-72 (Bibliography 43-55) for an extensive selection and to the Mando Festival Programmes published by the Konkani Bhasha Mandal in Panaji for recent compositions. Almeida, Mathew . 1988. Konkani Orthography. Panaji: Dalgado Konknni Akademi. Barreto, Lourdinho. 1984. Goemchem Git. Pustok 1 and 2. Panaji: Pedro Barreto, Printer. Barros de, Joseph. 1989. “The first Book to be printed in India”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 159. pp. 5-16. Barros de, Joseph. 1993. “The Clergy and the Revolt in Portuguese Goa”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 169. pp. 21-37. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). 2000. Goa and Portugal. History and Development. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). Goa´s formost Nationalist: José Inácio Candido de Loyola. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. (Loyola is mentioned in the mando Setembrachê Ekvissavêru). Bragança, Alfred. 1964. “Song and Music”, in: The Discovery of Goa. Panaji: Casa J.D. Fernandes. pp. 41-53. Coelho, Victor A. -

Pereira, Jose I Martins, Micael. 1984. Goa and Its Music

Pereira, Jose I Martins, Micael. 1984. Goa and its Music. No. 2. In: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragan9a, No. 145, pp. 19-112. Panaji, Goa. GOA & ITS MUSIC Jose Pereira & ~licael ~lartins (Continuation from N. 0 144) IV. THE HINDU-MUSLIM TUSSLE The irruption of the Turkish and Afghan invaders into Indian affairs, so disa straYs to the millenary life and culture of the subcontinent, became crucial in Goan history only after the extinction of Yadava and Kadamba rule. Hinduism, prostrate in the north before the Muslim blast, was in the south rallying its forces for last-but-one co_unter-attack (the last being the Maratha ). 3 Its headquarters were Vijayanagara, the City of Victory. ( ') The fire of Indian civilization, slowly smothered in its own ashes from the time of the Guptas, still radiated a cultural brilliance. Though consuming itself out in slow degrees, it twice worked up its dying energy to bright heat -first in Vijayanagara and then under the Mughal Empire- before it finally gave out. The involved perfection of Dravidian architectural forms, the systematization of a dualist logic and metaphysics, the codification of a stric ter musical system, the Carnati6, or South Indian ( as opposed to the less i ntellectuaiized Hindustani or North Indian) and a blossoming of devotional literature and song, are some of the achievements that culture owes to the City of Victory. The armies of the Hindu Revival struck triumphantly at the Muslim tyranny in the Deccan; Goa ohce again changed masters. ( 3 :!) During this period, Marathi settled down to peing the sacred language of Goan Hinduism. -

India – Goa – Evangelical Christians – Shiv Sena – RSS – Jamat-E-Islami

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND31233 Country: India Date: 2 February 2007 Keywords: India – Goa – Evangelical Christians – Shiv Sena – RSS – Jamat-e-Islami This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. What is the activity of the Bajrang Dal, Jamaat -E-Islam, Rashtriya Swayam Sevak and Shiv Sena against evangelical Christians in Goa? 2. What difficulties do evangelical Christians face in Goa? 3. Would the police in Goa condone and/or be involved in discrimination / persecution against evangelical Christians in Goa by these groups? RESPONSE 1. What is the activity of the above mentioned four groups against evangelical Christians in Goa? 2. What difficulties do evangelical Christians face in Goa? 3. Would the police in Goa condone and/or be involved in discrimination / persecution against evangelical Christians in Goa by these groups? The state of Goa has a significant Christian population. According to the 2001 India census, Goa has a Christian population of 359,568 on a total population of 1,347,668 (there are 886,551 Hindus and 92,210 Muslims). Christianity, and the Catholic Church in particular, has played a significant role in Goa’s history and since Goa’s 1962 integration into the Indian Union this has continued to be the case. Studies of the Goan Christian identity, such as Dr Charles Borges’ 2000 study, tend to emphasize the inclusion and participation of the Christian population in Goa’s social and political life (‘Population by religious communities’ (undated), Census of India website http://demotemp257.nic.in/httpdoc/Census_Data_2001/Census_data_finder/C_Series/Populat ion_by_religious_communities.htm – Accessed 31 January 2007 – Attachment 24; Borges, C.