Staging Der Ring Des Nibelungen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Música Y Pasión De Cosima Liszt Y Richard Wagner

A6 [email protected] VIDA SOCIAL JUEVES 14 DE MAYO DE 2020 Música y pasión de Cosima Liszt y Richard Wagner GRACIELA ALMENDRAS Fundado en 1876, l Festival de Bayreuth, que cada año se el festival realiza en julio, no solo hace noticia por su también E obligada cancelación a causa de la pande- suspendió mia, sino que también porque es primera vez en sus funcio- sus más de 140 años de historia que un Wagner nes durante no encabeza su organización. Ocurre que la bisnie- las grandes ta de Richard Wagner, el compositor alemán guerras. En precursor de este festival, está enferma y abando- julio iba a nó su cargo por un tiempo indefinido. celebrar su La historia de este evento data de 1870, cuando 109ª edi- Richard Wagner con su mujer, Cosima Liszt, visita- ción. En la ron la ciudad alemana de Bayreuth y consideraron foto, el que debía construirse un teatro más amplio, capaz teatro. de albergar los montajes y grandes orquestas que requerían las óperas de su autoría. Con el apoyo financiero principalmente de Luis II de Baviera, consiguieron abrir el teatro y su festival en 1876. Entonces, la relación entre Richard Wagner y FESTIVAL DE BAYREUTH su esposa, Cosima, seguía siendo mal vista: ella era 24 años menor que él e hija de uno de sus amigos, y habían comenzado una relación estando ambos casados. Pero a ellos eso poco les importó y juntos crearon un imperio en torno a la música. Cosima Liszt y Richard Wagner. En 1857, Cosima se casó con el pianista y Cosima Liszt (en la director de foto) nació en orquesta Bellagio, Italia, en alemán Hans 1837, hija de la con- von Bülow desa francoalemana (arriba), Marie d’Agoult y de alumno de su su amante, el conno- padre y amigo tado compositor de Wagner. -

Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen

The Pescadero Opera Society presents Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen Summer Season 2012 June 9th and 23rd, July 7th and 21th, August 4th The Pescadero Opera Society is extending its 2012 opera season by offering a summer course on Wagner’s Ring Cycle. This is the fourth time this course has been offered; previous courses were given rave reviews. The Ring consists of four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried and Gotterdämmerung, an opera mini-series which are connected to each other by storyline, characters and music. It is considered to be the greatest work of art ever written with some of the most extraordinary music on earth. The operas will be presented in two-week intervals throughout the summer; a fifth week is added to offer “A Tribute to Wagner,” a special event you won't want to miss. The format for presenting these four operas will be a bit different than during the regular season. Because this work is so complex and has so many layers, both in story and in music, before each opera there will a PowerPoint presentation. Listen to the wonderful one-hour introduction of “The Ring and I: The Passion, the Myth, the Mania” to find out what all the fuss is about: http://www.wnyc.org/articles/music/2004/mar/02/the-ring-and-i-the-passion-the-myth-the- mania/. Der Ring des Nibelungen is based on Ancient German and Norse mythology. Das Rheingold begins with the creation of the world and Gotterdammerung ends with the destruction of the gods. It includes gods, goddesses, Rhinemaidens, Valkyries, dwarfs, a dragon, a gold ring, a magic sword, a magic Tarnhelm, magic fire, and much more. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

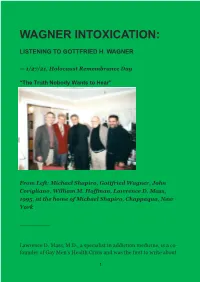

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

Notes on Wagner's Ring Cycle

THE RING CYCLE BACKGROUND FOR NC OPERA By Margie Satinsky President, Triangle Wagner Society April 9, 2019 Wagner’s famous Ring Cycle includes four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walkure, Siegfried, and Gotterdammerung. What’s so special about the Ring Cycle? Here’s what William Berger, author of Wagner without Fear, says: …the Ring is probably the longest chunk of music and/or drama ever put before an audience. It is certainly one of the best. There is nothing remotely like it. The Ring is a German Romantic view of Norse and Teutonic myth influenced by both Greek tragedy and a Buddhist sense of destiny told with a sociopolitical deconstruction of contemporary society, a psychological study of motivation and action, and a blueprint for a new approach to music and theater.” One of the most fascinating characteristics of the Ring is the number of meanings attributed to it. It has been seen as a justification for governments and a condemnation of them. It speaks to traditionalists and forward-thinkers. It is distinctly German and profoundly pan-national. It provides a lifetime of study for musicologists and thrilling entertainment. It is an adventure for all who approach it. SPECIAL FEATURES OF THE RING CYCLE Wagner was extremely critical of the music of his day. Unlike other composers, he not only wrote the music and the libretto, but also dictated the details of each production. The German word for total work of art, Gesamtkunstwerk, means the synthesis of the poetic, visual, musical, and dramatic arts with music subsidiary to drama. As a composer, Wagner was very interested in themes, and he uses them in The Ring Cycle in different ways. -

Wagner) Vortrag Am 21

Miriam Drewes Die Bühne als Ort der Utopie (Wagner) Vortrag am 21. August 2013 im Rahmen der „Festspiel-Dialoge“ der Salzburger Festspiele 2013 Anlässlich des 200. Geburtstags von Richard Wagner schreibt Christine Lemke-Matwey in „Der Zeit“: „Keine deutsche Geistesgröße ist so gründlich auserzählt worden, politisch, ästhetisch, in Büchern und auf der Bühne wie der kleine Sachse mit dem Samtbarrett. Und bei keiner fällt es so schwer, es zu lassen.“1 Allein zum 200. Geburtstag sind an die 3500 gedruckte Seiten Neuinterpretation zu Wagners Werk und Person entstanden. Ihre Bandbreite reicht vom Bericht biographischer Neuentdeckungen, über psychologische Interpretationen bis hin zur Wiederauflage längst überholter Aspekte in Werk und Wirkung. Inzwischen hat die Publizistik eine Stufe erreicht, die sich von Wagner entfernend vor allen Dingen auf die Rezeption von Werk und Schöpfer richtet und dabei mit durchaus ambivalenten Lesarten aufwartet. Begegnet man, wie der Musikwissenschaftler Wolfgang Rathert konzediert, Person und Werk naiv, begibt man sich alsbald auf vermintes ideologisches Terrain,2 auch wenn die Polemiken von Wagnerianern und Anti-Wagnerianern inzwischen nicht mehr gar so vehement und emphatisch ausfallen wie noch vor 100 oder 50 Jahren. Selbst die akademische Forschung hat hier, Rathert zufolge, nur wenig ausrichten können. Immerhin aber zeigt sie eines: die Beschäftigung mit Wagner ist nicht obsolet, im Gegenteil, die bis ins Ideologische reichende Rezeption führe uns die Ursache einer heute noch ausgesprochenen Produktivität vor Augen – sowohl diskursiv als auch auf die Bühne bezogen. Ich möchte mich in diesem Vortrag weniger auf diese neuesten Ergebnisse oder Pseudoergebnisse konzentrieren, als vielmehr darauf, in wieweit der Gedanke des Utopischen, der Richard Wagners theoretische Konzeption wie seine Opernkompositionen durchdringt, konturiert ist. -

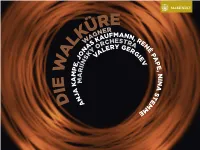

WAGNER / Рихард Вагнер DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (Conclusion) 1 Xii

lk a Waü GN r W , joNas k e e pe kY au r m iNs or f e ri C m i a a Val H k er e a m Y s N a t D j N G r N e , a r a r e G N i e é V p a p e , N i N a s t e e m m 2 Die Walküre Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (conclusion) 1 xii. Schwer wiegt mir der Waffen Wucht / My load of armour weighs heavy on me p18 2’28” DiE WAlkÜRE 2 xiii. Dritte Szene: Raste nun hier, gönne dir Ruh’! / Scene Three: Do stop here, and take a rest p18 8’56” (ThE VAlkyRiE / ВалькиРия) 3 xiv. Wo bist du, Siegmund? / Where are you, Siegmund? p19 3’49” 4 xv. Vierte Szene: Siegmund! Sieh auf mich! / Scene Four: Siegmund, look at me p19 10’55” Siegmund / Зигмунд...................................................................................................................................Jonas KAUFMANN / Йонас Кауфман 5 xvi. Du sahst der Walküre sehrenden Blick / you have seen the Valkyrie’s searing glance p20 4’27” hunding / Хундинг................................. ..............................................................................................Mikhail PETRENKO / михаил ПетренКо 6 xvii. So jung un schön erschimmerst du mir / So young and fair and dazzling you look p20 4’58” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René Pape / рене ПаПе 7 xviii. Funfte Szene: Zauberfest bezähmt ein Schlaf / Scene Five: Deep as a spell sleep subdues p21 3’01” Sieglinde / Зиглинда........................................................................................................................................................Anja -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Vierte Wiederaufnahme DIE WALKÜRE Erster Tag Des

Vierte Wiederaufnahme DIE WALKÜRE Erster Tag des Bühnenfestspiels Der Ring des Nibelungen von Richard Wagner Text vom Komponisten Mit deutschen und englischen Übertiteln Musikalische Leitung: Sebastian Weigle Inszenierung: Vera Nemirova Szenische Leitung der Wiederaufnahme: Hans Walter Richter Bühnenbild: Jens Kilian Kostüme: Ingeborg Bernerth Licht: Olaf Winter Video: Bibi Abel Dramaturgie: Malte Krasting Siegmund: Peter Wedd Ortlinde: Elizabeth Reiter Hunding: Taras Shtonda Waltraute: Nina Tarandek Wotan: James Rutherford Schwertleite: Katharina Magiera Sieglinde: Amber Wagner Helmwige: Ambur Braid Brünnhilde: Christiane Libor Siegrune: Karen Vuong Fricka: Claudia Mahnke Grimgerde: Stine Marie Fischer Gerhilde: Irina Simmes Rossweiße: Judita Nagyová Statisterie der Oper Frankfurt; Frankfurter Opern- und Museumsorchester Nachdem der Vorabend der Tetralogie Der Ring des Nibelungen von Richard Wagner (1813-1883) in der Saison 2009/10 auf Jens Kilians bereits legendärer „Frankfurter Scheibe“ Premiere gefeiert hatte, waren die Erwartungen groß, wie es weitergehen würde. Weder Publikum noch Presse zeigten sich enttäuscht: „Halbzeit beim Frankfurter Ring. Auch die Walküre in der Inszenierung von Vera Nemirova lebt wie schon das Rheingold vor allem vom Bühnenbild Jens Kilians. Die Premiere am Sonntagabend mit Generalmusikdirektor Sebastian Weigle am Pult des Frankfurter Museumsorchesters war eine musikalische Offenbarung auf Festspielniveau“, urteilte etwa Die Rheinpfalz. Nun ist die Produktion in ihrer vierten Wiederaufnahme an der Oper Frankfurt zu erleben, wobei geplant ist, dass sich der Ring – nach dem Auftakt mit der vierten Wiederaufnahme des Rheingolds in 2017/18 – in den beiden kommenden Spielzeiten mit weiteren Einzelaufführungen der folgenden Tage erneut schließen soll. Göttervater Wotan bereut den Raub des Rheingoldes und das Schmieden des Rings. Daher zeugt er die Geschwister Siegmund und Sieglinde sowie die Walküre Brünnhilde, die mit ihren Halbschwestern eine Armee gefallener Helden aufbauen soll. -

Gesamttext Als Download (PDF)

DER RING DES NIBELUNGEN Bayreuth 1976-1980 Eine Betrachtung der Inszenierung von Patrice Chéreau und eine Annäherung an das Gesamtkunstwerk Magisterarbeit in der Philosophischen Fakultät II (Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften) der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg vorgelegt von Jochen Kienbaum aus Gummersbach Der Ring 1976 - 1980 Inhalt Vorbemerkung Im Folgenden wird eine Zitiertechnik verwendet, die dem Leser eine schnelle Orientierung ohne Nachschlagen ermöglichen soll und die dabei gleichzeitig eine unnötige Belastung des Fußnotenapparates sowie über- flüssige Doppelnachweise vermeidet. Sie folgt dem heute gebräuchlichen Kennziffernsystem. Die genauen bibliographischen Daten eines Zitates können dabei über Kennziffern ermittelt werden, die in Klammern hinter das Zitat gesetzt werden. Dabei steht die erste Ziffer für das im Literaturverzeichnis angeführte Werk und die zweite Ziffer (nach einem Komma angeschlossen) für die Seitenzahl; wird nur auf eine Seitenzahl verwiesen, so ist dies durch ein vorgestelltes S. erkenntlich. Dieser Kennziffer ist unter Umständen der Name des Verfassers beigegeben, soweit dieser nicht aus dem Kontext eindeutig hervorgeht. Fußnoten im Text dienen der reinen Erläuterung oder Erweiterung des Haupttextes. Lediglich der Nachweis von Zitaten aus Zeitungsausschnitten erfolgt direkt in einer Fußnote. Beispiel: (Mann. 35,145) läßt sich über die Kennziffer 35 aufschlüs- seln als: Thomas Mann, Wagner und unsere Zeit. Aufsätze, Betrachtungen, Briefe. Frankfurt/M. 1983. S.145. Ausnahmen - Für folgende Werke wurden Siglen eingeführt: [GS] Richard Wagner, Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen in zehn Bän- den. Herausgegeben von Wolfgang Golther. Stuttgart 1914. Diese Ausgabe ist seitenidentisch mit der zweiten Auflage der "Gesammelten Schriften und Dichtungen" die Richard Wagner seit 1871 selbst herausgegeben hat. Golther stellte dieser Ausgabe lediglich eine Biographie voran und einen ausführlichen Anmerkungs- und Registerteil nach.