05-07-2019 Walkure Eve.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

By Richard Wagner 1856 Ride of the Valkyries

KNOWLEDGE ORGANISER: KEY PIECES OF MUSIC 6 BY RICHARD RIDE WAGNER OF THE 1856 VALKYRIES THE STORY—well, a short snippet of it... Wotan has 9 daughters. These are the Valkyries whose task it is to recover heroes fallen in battle and bring them back to Valhalla where they will protect Wotan’s fortress. Wotan hopes for a hero who will take a ring from the dragon. Wotan has two other children who live on Earth; twins called Siegmund and Sieglinde. They grow up separately but meet one day. Siegmund plans to battle Sieglinde’s husband as she claims he forced her to marry him. Wotan believes Siegmund wants to capture and keep the ring and won’t protect him. He sends one of his Valkyrie daughters to bring him to Valhalla but he refuses to go without his sister. She tries to help him in battle against her father’s wishes but sadly he dies. Meanwhile, the Valkyries congregate on the mountain-top, each carrying a dead hero and chattering excitedly when the daughter arrives with Sieglinde. Wotan is furious and plans to punish her. Prelude An introductory piece of music. A prelude often opens an act in an opera Act A musical, play or opera is often split into acts. There is often an interval between acts THE MUSIC THE COMPOSER Ride of the Valkyries is only part of a Wagner loved the brass section and even huge major work. It is taken from a cycle invented the Wagner Tuba which looks like of 4 massive operas known as The Ring a cross between a French horn and of the Nibelungs or The Ring for short. -

Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen

The Pescadero Opera Society presents Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen Summer Season 2012 June 9th and 23rd, July 7th and 21th, August 4th The Pescadero Opera Society is extending its 2012 opera season by offering a summer course on Wagner’s Ring Cycle. This is the fourth time this course has been offered; previous courses were given rave reviews. The Ring consists of four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried and Gotterdämmerung, an opera mini-series which are connected to each other by storyline, characters and music. It is considered to be the greatest work of art ever written with some of the most extraordinary music on earth. The operas will be presented in two-week intervals throughout the summer; a fifth week is added to offer “A Tribute to Wagner,” a special event you won't want to miss. The format for presenting these four operas will be a bit different than during the regular season. Because this work is so complex and has so many layers, both in story and in music, before each opera there will a PowerPoint presentation. Listen to the wonderful one-hour introduction of “The Ring and I: The Passion, the Myth, the Mania” to find out what all the fuss is about: http://www.wnyc.org/articles/music/2004/mar/02/the-ring-and-i-the-passion-the-myth-the- mania/. Der Ring des Nibelungen is based on Ancient German and Norse mythology. Das Rheingold begins with the creation of the world and Gotterdammerung ends with the destruction of the gods. It includes gods, goddesses, Rhinemaidens, Valkyries, dwarfs, a dragon, a gold ring, a magic sword, a magic Tarnhelm, magic fire, and much more. -

DEUTSCHES ELEKTRONEN-SYNCHROTRON F £*^ in Der HELMHOLTZ-GEMEINSCHAFT DESY 06-102 Hep-Ph/0607306 July 2006

DE06FA338 DEUTSCHES ELEKTRONEN-SYNCHROTRON f £*^ in der HELMHOLTZ-GEMEINSCHAFT DESY 06-102 hep-ph/0607306 July 2006 Charmed-Hadron Fragmentation Functions from CERN LEP1 Revisited B. A. Kniehl, G. Kramer IL Institut für Theoretische Physik, Universität Hamburg ISSN 0418-9833 NOTKESTRASSE 85 - 22607 HAMBURG DESY behält sich alle Rechte für den Fall der Schutzrechtserteilung und für die wirtschaftliche Verwertung der in diesem Bericht enthaltenen Informationen vor. DESY reserves all rights for commercial use of information included in this report, especially in case of filing application for or grant of patents. To be sure that your reports and preprints are promptly included in the HEP literature database send them to (if possible by air mail): DESY DESY Zentralbibliothek Bibliothek Notkestraße 85 Platanenallee 6 22607 Hamburg 15738 Zeuthen Germany Germany DESY 06-102 ISSN 0418-9833 July 2006 Charmed-Hadron Fragmentation Functions from CERN LEP1 Revisited Bernd A. Kniehl∗ and Gustav Kramer† II. Institut f¨ur Theoretische Physik, Universit¨at Hamburg, Luruper Chaussee 149, 22761 Hamburg, Germany (Dated: July 28, 2006) Abstract In Phys. Rev. D 58, 014014 (1998) and 71, 094013 (2005), we determined non-perturbative D0, + ∗+ + + D , D , Ds , and Λc fragmentation functions, both at leading and next-to-leading order in the MS factorization scheme, by fitting e+e− data taken by the OPAL Collaboration at CERN LEP1. The starting points for the evolution in the factorization scale µ were taken to be µ0 = 2mQ, where Q = c, b. For the reader’s convenience, in this Addendum, we repeat this analysis for µ0 = mQ, where the flavor thresholds of modern sets of parton density functions are located. -

Curtis Kheel Scripts, 1990-2007 (Bulk 2000-2005)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4b69r9wq No online items Curtis Kheel scripts, 1990-2007 (bulk 2000-2005) Finding aid prepared by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Curtis Kheel scripts, 1990-2007 PASC 343 1 (bulk 2000-2005) Title: Curtis Kheel scripts Collection number: PASC 343 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 8.5 linear ft.(17 boxes) Date (bulk): Bulk, 2000-2005 Date (inclusive): 1990-2007 (bulk 2000-2005) Abstract: Curtis Kheel is a television writer and supervising producer. The collection consists of scripts for the television series, most prominently the series, Charmed. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Kheel, Curtis Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Charmed Eloquence: Lhéritier's Representation of Female Literary

Charmed Eloquence: Lhéritier’s Representation of Female Literary Creativity in Late Seventeenth-Century France by Allison Stedman In 1690 when Marie-Catherine le Jumel de Barneville, comtesse d'Aulnoy decided to interpolate a fairy tale, "L'île de la félicité," into her first historical novel, L'histoire d'Hypolite, comte de Duglas, she did more than publish the first literary fairy tale of the French tradition.1 Hypolite not only provided a framework for introducing the fairy tale as a literary genre; it also launched a new hybrid publication strategy that would soon sweep printing houses all over Paris. This unprecedented literary trend—which I have chosen to call the novel/fairy-tale hybrid—involved the combination of fairy tales and novels by means of interpolation, framing, layering or juxtaposition. More than thirteen authors developed the genre between 1690 and 1715, and they produced a total of twenty-seven original works, sometimes at the rapid rate of two to three per year.2 In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, novel/fairy-tale hybrids were incredibly popular, frequently reprinted and widely circulated, with translations of some appearing as far away as England, Spain and Czecesolvakia.3 D'Aulnoy's Histoire d'Hypolite, for example, achieved more editions over the course of the eighteenth century than any other seventeenth-century literary work, with the exception of La Princesse de Clèves.4 In fact, the genre was so popular that it even experienced a brief revival between 1747 and 1759 when six new examples appeared. During the final decades of the eighteenth century, however, anthologists began pillaging the original editions of these works. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

Wagner's Parsifal by Roger Scruton Review

Wagner’s Parsifal by Roger Scruton review – in defence of the insufferable | Books | The Guardian 30/05/2020, 09:31 Wagner’s Parsifal by Roger Scruton review 8 in defence of the insufferable Nietzsche famously called Wagner’s last opera poisonous, but does its theme of redemption offer an antidote to our ills? Stuart Jeffries Sat 30 May 2020 07.30 BST An English National Opera production of Parsifal. Photograph: Tristram Kenton/The Guardian In his 1998 book On Hunting, Roger Scruton defended the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable. In his last, now posthumously published book, the philosopher who died in January stands up for the unbearable responsible for the insufferable. The unbearable? The megalomaniac, narcissistic, antisemitic monster Richard Wagner. And the insufferable? The life-hating curse on the senses that was his last opera. So at least argued Nietzsche, who damned Wagner’s Parsifal with the histrionics only a former devotee can muster. “Parsifal,” he snarled in the essay “Nietzsche Contra Wagner”, “is a work of perfidy, of vindictiveness, of a secret attempt to poison the presuppositions of life – a bad work.” Parsifal, which received its premiere at Bayreuth in 1882, unfolds in an unsavoury twilight milieu of death, curdling blood and toxic sex. The castle of Montsalvat is home to a community of grimly celibate knights who guard the Holy Grail, a chalice holding the blood https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/may/30/wagners-parsifal-by-roger-scruton-review-in-defence-of-the-insufferable Page 1 of 4 Wagner’s Parsifal by Roger Scruton review – in defence of the insufferable | Books | The Guardian 30/05/2020, 09:31 of Christ collected after the crucifixion, along with the Holy Lance with which he was pierced. -

The Wagner Society Members Who Were Lucky Enough to Get Tickets Was a Group I Met Who Had Come from Yorkshire

HARMONY No 264 Spring 2019 HARMONY 264: March 2019 CONTENTS 3 From the Chairman Michael Bousfield 4 AGM and “No Wedding for Franz Liszt” Robert Mansell 5 Cover Story: Project Salome Rachel Nicholls 9 Music Club of London Programme: Spring / Summer 2019 Marjorie Wilkins Ann Archbold 18 Music Club of London Christmas Dinner 2018 Katie Barnes 23 Visit to Merchant Taylors’ Hall Sally Ramshaw 25 Dame Gwyneth Jones’ Masterclasses at Villa Wahnfried Roger Lee 28 Sir John Tomlinson’s masterclasses with Opera Prelude Katie Barnes 30 Verdi in London: Midsummer Opera and Fulham Opera Katie Barnes 33 Mastersingers: The Road to Valhalla (1) with Sir John Tomlinson Katie Barnes 37 Mastersingers: The Road to Valhalla (2) with Dame Felicity Palmer 38 Music Club of London Contacts Cover picture: Mastersingers alumna Rachel Nicholls by David Shoukry 2 FROM THE CHAIRMAN We are delighted to present the second issue of our “online” Harmony magazine and I would like to extend a very big thank you to Roger Lee who has produced it, as well as to Ann Archbold who will be editing our Newsletter which is more specifically aimed at members who do not have a computer. The Newsletter package will include the booking forms for the concerts and visits whose details appear on pages 9 to 17. Overseas Tours These have provided a major benefit to many of our members for as long as any us can recall – and it was a source of great disappointment when we had to suspend these. Your committee have been exploring every possible option to offer an alternative and our Club Secretary, Ian Slater, has done a great deal of work in this regard. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

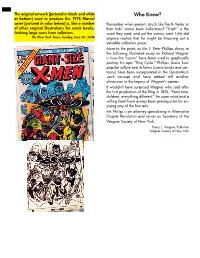

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought.