Notes on Wagner's Ring Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Música Y Pasión De Cosima Liszt Y Richard Wagner

A6 [email protected] VIDA SOCIAL JUEVES 14 DE MAYO DE 2020 Música y pasión de Cosima Liszt y Richard Wagner GRACIELA ALMENDRAS Fundado en 1876, l Festival de Bayreuth, que cada año se el festival realiza en julio, no solo hace noticia por su también E obligada cancelación a causa de la pande- suspendió mia, sino que también porque es primera vez en sus funcio- sus más de 140 años de historia que un Wagner nes durante no encabeza su organización. Ocurre que la bisnie- las grandes ta de Richard Wagner, el compositor alemán guerras. En precursor de este festival, está enferma y abando- julio iba a nó su cargo por un tiempo indefinido. celebrar su La historia de este evento data de 1870, cuando 109ª edi- Richard Wagner con su mujer, Cosima Liszt, visita- ción. En la ron la ciudad alemana de Bayreuth y consideraron foto, el que debía construirse un teatro más amplio, capaz teatro. de albergar los montajes y grandes orquestas que requerían las óperas de su autoría. Con el apoyo financiero principalmente de Luis II de Baviera, consiguieron abrir el teatro y su festival en 1876. Entonces, la relación entre Richard Wagner y FESTIVAL DE BAYREUTH su esposa, Cosima, seguía siendo mal vista: ella era 24 años menor que él e hija de uno de sus amigos, y habían comenzado una relación estando ambos casados. Pero a ellos eso poco les importó y juntos crearon un imperio en torno a la música. Cosima Liszt y Richard Wagner. En 1857, Cosima se casó con el pianista y Cosima Liszt (en la director de foto) nació en orquesta Bellagio, Italia, en alemán Hans 1837, hija de la con- von Bülow desa francoalemana (arriba), Marie d’Agoult y de alumno de su su amante, el conno- padre y amigo tado compositor de Wagner. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

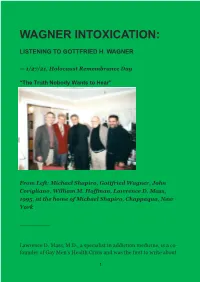

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

RWVI WAGNER NEWS – Nr

RWVI WAGNER NEWS – Nr. 7 – 01/2018 – deutsch – english – français Wir möchten die Ortsverbände höflich bitten, zur Übermittlung von Nachrichten und Veranstaltungsankündigungen diese Links zu benutzen Link zur Übermittlung von Nachrichten für die RWVI Webseiten: http://www.richard-wagner.org/send-news/ Link zur Übermittlung von Veranstaltungshinweisen für die RWVI Webseiten. http://www.richard-wagner.org/send-event/ Danke für ihre Mithilfe. Liebe Wagnergemeinde weltweit, Das nun zu Ende gehende Jahr 2017 war geprägt von großen politischen Veränderungen, deren Umstände und Auswüchse in den Medien sattsam kritisch gewürdigt wurden. Gleichwohl aber markieren Ereignisse wie wir Sie in einigen Staaten derzeit erleben, Entwicklungen, die wir sicher nicht nur begrüßen. Humanismus, Aufklärung und Gewaltenteilung waren lange Zeit unumstrittene Eckpfeiler unseres Zusammenlebens und Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Henry Dunant, Elihu Root, José Martí oder Yoko Ono mögen exemplarisch als einige, der vielen von uns denkbaren Vorbilder in dieser Hinsicht gelten. Auch Komponisten spielten früher eine gewichtige gesellschaftliche Rolle und repräsentierten oder beeinflussten die Menschen in ihrem Handeln. Gerade die Tatsache aber, dass Musik heute fast ohne Ausnahme zum gesichtslosen Konsumartikel geworden ist, sagt viel aus. Wen würden Sie heute als eine „große Persönlichkeit“ mit bedeutendem Einfluss unter den lebenden Komponisten bezeichnen? Große Persönlichkeiten waren und sind aber meist nicht unumstritten, biographische Brüche und punktuelles Versagen gehören zum Leben leider dazu. Richard Wagner ist hierfür ein beredtes Beispiel und wir alle kennen die Angriffsflächen, die unser vielseitiger und viel produzierender Meister bis heute bietet. Geschichte ist leider ebenso wenig abzuändern wie eben diese Schattenseiten des Genies. Die Zeit bleibt nicht stehen und wir sollten gerade bei Richard Wagner immer vor allem und immer wieder neu auf die Taten in Form seiner ewig gültigen Musikdramen blicken, die eben genau das Gegenteil einer Blaupause für die aktuellen Entwicklungen sind. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Ebook Download Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around

WAGNERS RING TURNING THE SKY AROUND - AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RING OF THE NIBELUNG 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M Owen Lee | 9780879101862 | | | | | Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around - An Introduction to the Ring of the Nibelung 1st edition PDF Book It is even possible for the orchestra to convey ideas that are hidden from the characters themselves—an idea that later found its way into film scores. Unfamiliarity with Wagner constitutes an ignorance of, well, Wagnerian proportions. Some of my friends have seen far more than these. This section does not cite any sources. Digital watches chime the hour in half-diminished seventh chords. The daughters of the Rhine come up and pull Hagen into the depth of the Rhine. The plot synopses were helpful, but some of the deep psychological analysis was a bit boring. Next he encounters Wotan his grandfather , quarrels with him and cuts Wotan's staff of power in half. The next possessor of the ring, the giant Fafner, consumed with greed and lust for power, kills his brother, Fasolt, taking the spoils to the deep forest while the gods enter Valhalla to some of the most glorious and ironically triumphant music imaginable. Has underlining on pages. John shares his recipe for Nectar of the Gods. April Learn how and when to remove this template message. It's actually OK because that's what Wotan decreed for her anyway: First one up there shall have you. See Article History. Politics and music often go together. It left me at a whole new level of self-awareness, and has for all the years that have followed given me pleasures and insights that have enriched my life. -

Staging Der Ring Des Nibelungen

John Lindner Professor Weinstock Staging Der Ring des Nibelungen: The Revolutionary Ideas of Adolphe Appia and their Roots in Schopenhaurean Aesthetic Principles “For Apollo was not only the god of music; he was also the god of light.” - Glérolles: April, 1911) Richard Wagner’s set design in Der Ring des Nibelungen differed from that of later adaptations in the 20th century. Before Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner, the grandsons of the composer, allowed for modern stage design theory to penetrate the walls of Bayreuth, nothing in the production of Wagner’s operas was noticeably changed since his death. Richard Wagner disliked the two-dimensional sets he was accustomed to using, composed of highly ornamental and richly painted backdrops that strove for a natural realism. For all his genius in operatic creation (specifically the musical composition), Wagner never fully challenged the contemporary method of staging in Der Ring des Nibelungen. In his writings he bemoans having to deal with them at all, yet never does anything of much significance about it. The changes he made were topical in nature, such as the sinking the orchestra pit at the Bayreuth. Shortly after Wagner’s death, Adolphe Appia (1862-1928) led a revolution in stage design, letting light and the movement of the actors, as determined by the music, to sculpt spaces. Appia saw the 1 ability for light to change and shape feelings, much in the same way that Wagner’s music did. A stage comprised of objects with three-dimensional depth allowed for different lighting conditions, not only by location of the physical lights and their direction, but more importantly, by letting the light react off of the stage and characters in a delicate precision of lit form, shade and shadow. -

Wagner) Vortrag Am 21

Miriam Drewes Die Bühne als Ort der Utopie (Wagner) Vortrag am 21. August 2013 im Rahmen der „Festspiel-Dialoge“ der Salzburger Festspiele 2013 Anlässlich des 200. Geburtstags von Richard Wagner schreibt Christine Lemke-Matwey in „Der Zeit“: „Keine deutsche Geistesgröße ist so gründlich auserzählt worden, politisch, ästhetisch, in Büchern und auf der Bühne wie der kleine Sachse mit dem Samtbarrett. Und bei keiner fällt es so schwer, es zu lassen.“1 Allein zum 200. Geburtstag sind an die 3500 gedruckte Seiten Neuinterpretation zu Wagners Werk und Person entstanden. Ihre Bandbreite reicht vom Bericht biographischer Neuentdeckungen, über psychologische Interpretationen bis hin zur Wiederauflage längst überholter Aspekte in Werk und Wirkung. Inzwischen hat die Publizistik eine Stufe erreicht, die sich von Wagner entfernend vor allen Dingen auf die Rezeption von Werk und Schöpfer richtet und dabei mit durchaus ambivalenten Lesarten aufwartet. Begegnet man, wie der Musikwissenschaftler Wolfgang Rathert konzediert, Person und Werk naiv, begibt man sich alsbald auf vermintes ideologisches Terrain,2 auch wenn die Polemiken von Wagnerianern und Anti-Wagnerianern inzwischen nicht mehr gar so vehement und emphatisch ausfallen wie noch vor 100 oder 50 Jahren. Selbst die akademische Forschung hat hier, Rathert zufolge, nur wenig ausrichten können. Immerhin aber zeigt sie eines: die Beschäftigung mit Wagner ist nicht obsolet, im Gegenteil, die bis ins Ideologische reichende Rezeption führe uns die Ursache einer heute noch ausgesprochenen Produktivität vor Augen – sowohl diskursiv als auch auf die Bühne bezogen. Ich möchte mich in diesem Vortrag weniger auf diese neuesten Ergebnisse oder Pseudoergebnisse konzentrieren, als vielmehr darauf, in wieweit der Gedanke des Utopischen, der Richard Wagners theoretische Konzeption wie seine Opernkompositionen durchdringt, konturiert ist. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Apocalypticism in Wagner's Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York

Title Page Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York University, 2015 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Woodrow Steinken It was defended on March 23, 2021 and approved by James Cassaro, Professor, Music Adriana Helbig, Associate Professor, Music David Levin, Professor, Germanic Studies Dan Wang, Assistant Professor, Music Dissertation Director: Olivia Bloechl Professor, Music ii Copyright © by Woodrow Steinken 2021 iii Abstract Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring Woodrow Steinken, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation traces the history of apocalypticism, broadly conceived, and its realization on the operatic stage by Richard Wagner and those who have adapted his works since the late nineteenth century. I argue that Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), presents colloquial conceptions of time, space, and nature via supernatural, divine characters who often frame the world in terms of non-rational metaphysics. Primary among these minor roles is Erda, the personification of the primordial earth. Erda’s character prophesies the end of the world in Das Rheingold, a prophecy undone later in Siegfried by Erda’s primary interlocutor and chief of the gods, Wotan. I argue that Erda’s role changes in various stage productions of the Ring, and these changes bespeak a shifting attachment between humanity, the earth, and its imagined apocalyptic demise.