Diegeheimnissederformbeirich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series Editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University Signale: Modern German Letters, Cultures, and Thought publishes new English- language books in literary studies, criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history pertaining to the German-speaking world, as well as translations of im- portant German-language works. Signale construes “modern” in the broadest terms: the series covers topics ranging from the early modern period to the present. Signale books are published under a joint imprint of Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library in electronic and print formats. Please see http://signale.cornell.edu/. The Total Work of Art in European Modernism David Roberts A Signale Book Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Ithaca, New York Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library gratefully acknowledge the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the publication of this volume. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, David, 1937– The total work of art in European modernism / David Roberts. p. cm. — (Signale : modern German letters, cultures, and thought) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5023-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modernism (Aesthetics) 2. -

SM358-Voyager Quartett-Book-Lay06.Indd

WAGNER MAHLER BOTEN DER LIEBE VOYAGER QUARTET TRANSCRIPTED AND RECOMPOSED BY ANDREAS HÖRICHT RICHARD WAGNER TRISTAN UND ISOLDE 01 Vorspiel 9:53 WESENDONCK 02 I Der Engel 3:44 03 II Stehe still! 4:35 04 III Im Treibhaus 5:30 05 IV Schmerzen 2:25 06 V Träume 4:51 GUSTAV MAHLER STREICHQUARTETT NR. 1.0, A-MOLL 07 I Moderato – Allegro 12:36 08 II Adagietto 11:46 09 III Adagio 8:21 10 IV Allegro 4:10 Total Time: 67:58 2 3 So geht das Voyager Quartet auf Seelenwanderung, überbringt klingende BOTEN DER LIEBE An Alma, Mathilde und Isolde Liebesbriefe, verschlüsselte Botschaften und geheime Nachrichten. Ein Psychogramm in betörenden Tönen, recomposed für Streichquartett, dem Was soll man nach der Transkription der „Winterreise“ als Nächstes tun? Ein Medium für spirituelle Botschaften. Die Musik erhält hier den Vorrang, den Streichquartett von Richard Wagner oder Gustav Mahler? Hat sich die Musikwelt Schopenhauer ihr zugemessen haben wollte, nämlich „reine Musik solle das nicht schon immer gewünscht? Geheimnisse künden, die sonst keiner wissen und sagen kann.“ Vor einigen Jahren spielte das Voyager Quartet im Rahmen der Bayreuther Andreas Höricht Festspiele ein Konzert in der Villa Wahnfried. Der Ort faszinierte uns über die Maßen und so war ein erster Eckpunkt gesetzt. Die Inspiration kam dann „Man ist sozusagen selbst nur ein Instrument, auf dem das Universum spielt.“ wieder durch Franz Schubert. In seinem Lied „Die Sterne“ werden eben diese Gustav Mahler als „Bothen der Liebe“ besungen. So fügte es sich, dass das Voyager Quartet, „Frauen sind die Musik des Lebens.“ das sich ja auf Reisen in Raum und Zeit begibt, hier musikalische Botschaften Richard Wagner versendet, nämlich Botschaften der Liebe von Komponisten an ihre Musen. -

Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen

The Pescadero Opera Society presents Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen Summer Season 2012 June 9th and 23rd, July 7th and 21th, August 4th The Pescadero Opera Society is extending its 2012 opera season by offering a summer course on Wagner’s Ring Cycle. This is the fourth time this course has been offered; previous courses were given rave reviews. The Ring consists of four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried and Gotterdämmerung, an opera mini-series which are connected to each other by storyline, characters and music. It is considered to be the greatest work of art ever written with some of the most extraordinary music on earth. The operas will be presented in two-week intervals throughout the summer; a fifth week is added to offer “A Tribute to Wagner,” a special event you won't want to miss. The format for presenting these four operas will be a bit different than during the regular season. Because this work is so complex and has so many layers, both in story and in music, before each opera there will a PowerPoint presentation. Listen to the wonderful one-hour introduction of “The Ring and I: The Passion, the Myth, the Mania” to find out what all the fuss is about: http://www.wnyc.org/articles/music/2004/mar/02/the-ring-and-i-the-passion-the-myth-the- mania/. Der Ring des Nibelungen is based on Ancient German and Norse mythology. Das Rheingold begins with the creation of the world and Gotterdammerung ends with the destruction of the gods. It includes gods, goddesses, Rhinemaidens, Valkyries, dwarfs, a dragon, a gold ring, a magic sword, a magic Tarnhelm, magic fire, and much more. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

Citymac 2018

CityMac 2018 City, University of London, 5–7 July 2018 Sponsored by the Society for Music Analysis and Blackwell Wiley Organiser: Dr Shay Loya Programme and Abstracts SMA If you are using this booklet electronically, click on the session you want to get to for that session’s abstract. Like the SMA on Facebook: www.facebook.com/SocietyforMusicAnalysis Follow the SMA on Twitter: @SocMusAnalysis Conference Hashtag: #CityMAC Thursday, 5 July 2018 09.00 – 10.00 Registration (College reception with refreshments in Great Hall, Level 1) 10.00 – 10.30 Welcome (Performance Space); continued by 10.30 – 12.30 Panel: What is the Future of Music Analysis in Ethnomusicology? Discussant: Bryon Dueck Chloë Alaghband-Zadeh (Loughborough University), Joe Browning (University of Oxford), Sue Miller (Leeds Beckett University), Laudan Nooshin (City, University of London), Lara Pearson (Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetic) 12.30 – 14.00 Lunch (Great Hall, Level 1) 14.00 – 15.30 Session 1 Session 1a: Analysing Regional Transculturation (PS) Chair: Richard Widdess . Luis Gimenez Amoros (University of the Western Cape): Social mobility and mobilization of Shona music in Southern Rhodesia and Zimbabwe . Behrang Nikaeen (Independent): Ashiq Music in Iran and its relationship with Popular Music: A Preliminary Report . George Pioustin: Constructing the ‘Indigenous Music’: An Analysis of the Music of the Syrian Christians of Malabar Post Vernacularization Session 1b: Exploring Musical Theories (AG08) Chair: Kenneth Smith . Barry Mitchell (Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance): Do the ideas in André Pogoriloffsky's The Music of the Temporalists have any practical application? . John Muniz (University of Arizona): ‘The ear alone must judge’: Harmonic Meta-Theory in Weber’s Versuch . -

Are Wagner's Views of 'Redemption'

Are Wagner’s views of ‘Redemption’ relevant for the Twenty-first Century? Richard H. Bell 1 Introduction It is universally acknowledged that all the operas in the ‘Wagnerian canon’ to a greater or lesser extent concern redemption. Strictly speaking redemption (‘Erlösung’) means freeing a prisoner, captive or slave by paying a ransom. Wagner, like many others, employs the term as a metaphor, often as a ‘dead metaphor’;1 but, as will become clear, the essence of redemption for Wagner lies in the realm of ‘myth’. Further, for Wagner redemption is multi-dimen- sional2 and sometimes highly ambiguous. This reflects his reluc- tance to make his intentions too obvious should this impair ‘a pro- per understanding of the work in question’.3 The complexity of his thinking on redemption means that there are many avenues to explore when considering its relevance for the twenty-first century. To make this manageable I restrict my examples to Das Rheingold, Götterdämmerung, Tristan und Isolde, and Parsifal, and consider redemption under five aspects, all of which are interrelated: 1. social/political/economic; 2. psychologi- cal; 3. existential; 4. cosmological; 5. religious. Since all these ulti- 1 In a dead metaphor no thought is given to the fact that a metaphor is being employed, e.g. ‘leaf of the book’. 2 Cf. Claus-Dieter Osthövener, Konstellationen des Erlösungsgedankens, in: wag- nerspectrum 2/2009: Bayreuther Theologie, Würzburg 2009, p. 51–80. 3 Wagner’s letter to August Röckel, 25/26 January 1854, in: Stewart Spencer and Barry Millington (ed.), Selected Letters of Richard Wagner, London 1987, p. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Richard Wagner Der Fliegende Holländer WWV 63

1 Richard Wagner Der Fliegende Holländer WWV 63 Medien in der Musikbücherei am Wilhelmspalais Zusammengestellt von Gertraud Voss-Krueger 2 Notenausgaben/Tonträger/Sekundärliteratur Partituren: Sämtliche Werke / hrsg. im Auftr. .in Verbindung mit der Bayerischen Akademie der Schönen Künste, München. Begr. von Carl Dahlhaus. Bd 4, 1. Der fliegende Holländer : romantische Oper in drei Aufzügen (Urfassung 1841) ; Ouvertüre, ÉêëíÉê=^ìÑòìÖ=EkêK=N=J=PF und 1. Hälfte des zweiten Aufzugs (Nr. 4) / hrsg. von Isolde Vetter. - Partitur - c 1983. - X, 254 S. SY: W1/Wag Bd 4, 2. Der fliegende Holländer : romantische Oper in drei Aufzügen (Urfassung 1841) ; OK=e®äÑíÉ=ÇÉë=òïÉáíÉå=^ìÑòìÖë=EkêK=RJSF=ìåÇ=ÇêáííÉê ^ìÑòìÖ=EkêK=TJUF / hrsg. von Isolde Vetter. - Partitur - c 1983. - 264 S. SY: W1/Wag Bd. 4, 3. Der fliegende Holländer : romantische Oper in drei Aufzügen ; WWV 63 / Fassung 1842 - 1880) ; ÉêëíÉê=ìåÇ=òïÉáíÉê=^ìÑòìÖ=ElìîÉêíΩêÉI kêK=N=J=SF - Partitur - 2000. - XIV, 361 S. SY: W1/Wag Bd. 4, 4. Der fliegende Holländer : romantische Oper in drei Aufzügen ; WWV 63 / (Fassung 1842 - 1880) ; ÇêáííÉê=^ìÑòìÖ=EkêK=T=J=U ), Anhang und Kritischer Bericht / hrsg. von Egon Voss. Kritischer Bericht hrsg. von Isolde Vetter und Egon Voss. - Partitur - 2001. - 397 S. SY: W1/Wag The flying dutchman / Richard Wagner. Ed. by Felix Weingartner. - Full score - New York : Dover , 1988. - 415 S. Text deutsch, englisch, italienisch ISBN 0-486-25629-4 50.80 SY: T11/Wag Der fliegende Hollaender = The flying dutchman / Richard Wagner. - Studienpartitur, [Neudruck] - London [u.a.] : Eulenburg, 2007. - X, 686 S. Text deutsch, englisch, italienisch SY: T21/Wag Klavierauszug: Der fliegende Holländer : WWV 63 ; romantische Oper in drei Aufzügen ; Urfassung 1841 ; herausgegeben nach dem Text der Richard-Wagner-Gesamtausgabe = The flying Dutchman / Richard Wagner. -

Staging Der Ring Des Nibelungen

John Lindner Professor Weinstock Staging Der Ring des Nibelungen: The Revolutionary Ideas of Adolphe Appia and their Roots in Schopenhaurean Aesthetic Principles “For Apollo was not only the god of music; he was also the god of light.” - Glérolles: April, 1911) Richard Wagner’s set design in Der Ring des Nibelungen differed from that of later adaptations in the 20th century. Before Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner, the grandsons of the composer, allowed for modern stage design theory to penetrate the walls of Bayreuth, nothing in the production of Wagner’s operas was noticeably changed since his death. Richard Wagner disliked the two-dimensional sets he was accustomed to using, composed of highly ornamental and richly painted backdrops that strove for a natural realism. For all his genius in operatic creation (specifically the musical composition), Wagner never fully challenged the contemporary method of staging in Der Ring des Nibelungen. In his writings he bemoans having to deal with them at all, yet never does anything of much significance about it. The changes he made were topical in nature, such as the sinking the orchestra pit at the Bayreuth. Shortly after Wagner’s death, Adolphe Appia (1862-1928) led a revolution in stage design, letting light and the movement of the actors, as determined by the music, to sculpt spaces. Appia saw the 1 ability for light to change and shape feelings, much in the same way that Wagner’s music did. A stage comprised of objects with three-dimensional depth allowed for different lighting conditions, not only by location of the physical lights and their direction, but more importantly, by letting the light react off of the stage and characters in a delicate precision of lit form, shade and shadow. -

WAGNER / Рихард Вагнер DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (Conclusion) 1 Xii

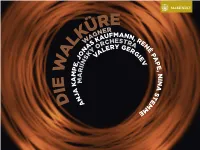

lk a Waü GN r W , joNas k e e pe kY au r m iNs or f e ri C m i a a Val H k er e a m Y s N a t D j N G r N e , a r a r e G N i e é V p a p e , N i N a s t e e m m 2 Die Walküre Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (conclusion) 1 xii. Schwer wiegt mir der Waffen Wucht / My load of armour weighs heavy on me p18 2’28” DiE WAlkÜRE 2 xiii. Dritte Szene: Raste nun hier, gönne dir Ruh’! / Scene Three: Do stop here, and take a rest p18 8’56” (ThE VAlkyRiE / ВалькиРия) 3 xiv. Wo bist du, Siegmund? / Where are you, Siegmund? p19 3’49” 4 xv. Vierte Szene: Siegmund! Sieh auf mich! / Scene Four: Siegmund, look at me p19 10’55” Siegmund / Зигмунд...................................................................................................................................Jonas KAUFMANN / Йонас Кауфман 5 xvi. Du sahst der Walküre sehrenden Blick / you have seen the Valkyrie’s searing glance p20 4’27” hunding / Хундинг................................. ..............................................................................................Mikhail PETRENKO / михаил ПетренКо 6 xvii. So jung un schön erschimmerst du mir / So young and fair and dazzling you look p20 4’58” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René Pape / рене ПаПе 7 xviii. Funfte Szene: Zauberfest bezähmt ein Schlaf / Scene Five: Deep as a spell sleep subdues p21 3’01” Sieglinde / Зиглинда........................................................................................................................................................Anja -

Read Book Wagner on Conducting

WAGNER ON CONDUCTING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Wagner,Edward Dannreuther | 118 pages | 01 Mar 1989 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486259321 | English | New York, United States Richard Wagner | Biography, Compositions, Operas, & Facts | Britannica Impulsive and self-willed, he was a negligent scholar at the Kreuzschule, Dresden , and the Nicholaischule, Leipzig. He frequented concerts, however, taught himself the piano and composition , and read the plays of Shakespeare, Goethe, and Schiller. Wagner, attracted by the glamour of student life, enrolled at Leipzig University , but as an adjunct with inferior privileges, since he had not completed his preparatory schooling. Although he lived wildly, he applied himself earnestly to composition. Because of his impatience with all academic techniques, he spent a mere six months acquiring a groundwork with Theodor Weinlig, cantor of the Thomasschule; but his real schooling was a close personal study of the scores of the masters, notably the quartets and symphonies of Beethoven. He failed to get the opera produced at Leipzig and became conductor to a provincial theatrical troupe from Magdeburg , having fallen in love with one of the actresses of the troupe, Wilhelmine Minna Planer, whom he married in In , fleeing from his creditors, he decided to put into operation his long-cherished plan to win renown in Paris, but his three years in Paris were calamitous. Living with a colony of poor German artists, he staved off starvation by means of musical journalism and hackwork. In , aged 29, he gladly returned to Dresden, where Rienzi was triumphantly performed on October The next year The Flying Dutchman produced at Dresden, January 2, was less successful, since the audience expected a work in the French-Italian tradition similar to Rienzi and was puzzled by the innovative way the new opera integrated the music with the dramatic content.