4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan Und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

05-11-2019 Gotter Eve.Indd

Synopsis Prologue Mythical times. At night in the mountains, the three Norns, daughters of Erda, weave the rope of destiny. They tell how Wotan ordered the World Ash Tree, from which his spear was once cut, to be felled and its wood piled around Valhalla. The burning of the pyre will mark the end of the old order. Suddenly, the rope breaks. Their wisdom ended, the Norns descend into the earth. Dawn breaks on the Valkyries’ rock, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerge. Having cast protective spells on Siegfried, Brünnhilde sends him into the world to do heroic deeds. As a pledge of his love, Siegfried gives her the ring that he took from the dragon Fafner, and she offers her horse, Grane, in return. Siegfried sets off on his travels. Act I In the hall of the Gibichungs on the banks of the Rhine, Hagen advises his half- siblings, Gunther and Gutrune, to strengthen their rule through marriage. He suggests Brünnhilde as Gunther’s bride and Siegfried as Gutrune’s husband. Since only the strongest hero can pass through the fire on Brünnhilde’s rock, Hagen proposes a plan: A potion will make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde and fall in love with Gutrune. To win her, he will claim Brünnhilde for Gunther. When Siegfried’s horn is heard from the river, Hagen calls him ashore. Gutrune offers him the potion. Siegfried drinks and immediately confesses his love for her.Ð When Gunther describes the perils of winning his chosen bride, Siegfried offers to use the Tarnhelm to transform himself into Gunther. -

SM358-Voyager Quartett-Book-Lay06.Indd

WAGNER MAHLER BOTEN DER LIEBE VOYAGER QUARTET TRANSCRIPTED AND RECOMPOSED BY ANDREAS HÖRICHT RICHARD WAGNER TRISTAN UND ISOLDE 01 Vorspiel 9:53 WESENDONCK 02 I Der Engel 3:44 03 II Stehe still! 4:35 04 III Im Treibhaus 5:30 05 IV Schmerzen 2:25 06 V Träume 4:51 GUSTAV MAHLER STREICHQUARTETT NR. 1.0, A-MOLL 07 I Moderato – Allegro 12:36 08 II Adagietto 11:46 09 III Adagio 8:21 10 IV Allegro 4:10 Total Time: 67:58 2 3 So geht das Voyager Quartet auf Seelenwanderung, überbringt klingende BOTEN DER LIEBE An Alma, Mathilde und Isolde Liebesbriefe, verschlüsselte Botschaften und geheime Nachrichten. Ein Psychogramm in betörenden Tönen, recomposed für Streichquartett, dem Was soll man nach der Transkription der „Winterreise“ als Nächstes tun? Ein Medium für spirituelle Botschaften. Die Musik erhält hier den Vorrang, den Streichquartett von Richard Wagner oder Gustav Mahler? Hat sich die Musikwelt Schopenhauer ihr zugemessen haben wollte, nämlich „reine Musik solle das nicht schon immer gewünscht? Geheimnisse künden, die sonst keiner wissen und sagen kann.“ Vor einigen Jahren spielte das Voyager Quartet im Rahmen der Bayreuther Andreas Höricht Festspiele ein Konzert in der Villa Wahnfried. Der Ort faszinierte uns über die Maßen und so war ein erster Eckpunkt gesetzt. Die Inspiration kam dann „Man ist sozusagen selbst nur ein Instrument, auf dem das Universum spielt.“ wieder durch Franz Schubert. In seinem Lied „Die Sterne“ werden eben diese Gustav Mahler als „Bothen der Liebe“ besungen. So fügte es sich, dass das Voyager Quartet, „Frauen sind die Musik des Lebens.“ das sich ja auf Reisen in Raum und Zeit begibt, hier musikalische Botschaften Richard Wagner versendet, nämlich Botschaften der Liebe von Komponisten an ihre Musen. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

Spring 2008-Final

Wagneriana Endloser Grimm! Ewiger Gram! Spring 2008 Der Traurigste bin ich von Allen! Volume 5, Number 2 —Die Walküre From the Editor ven though the much-awaited concert of the Wagner/Liszt piano transcriptions was canceled due to un- avoidable circumstances (the musicians were unable to obtain a visa), the winter and early spring months E brought several stimulating events. On January 19, Vice President Erika Reitshamer gave an audiovisual presentation on Wagner’s early opera Das Liebesverbot. This well-attended event was augmented by photocopies of extended excerpts from the libretto, with frequently amusing commentary by the presenter on Wagner’s influences and foreshadowings of his future operas. February 23 brought the excellent talk by Professor Hans Rudolf Vaget of Smith College. Professor Vaget spoke about Wagner’s English biographer Ernest Newman, whose seminal four-volume book The Life of Richard Wagner has never been surpassed in its thoroughness. In the early part of the twentieth century, the music critic Newman served as a counterbalance to his fellow countryman Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Wagner’s son-in-law and an ardent Nazi. The talk also included aspects of Thomas Mann’s fictional writings on Wagner, as well as the philoso- pher and musician Theodor Adorno and Wagner’s other son-in-law Franz Beidler. On April 19 we learned the extent of Buddhism’s influence on Wagner’s operas thanks to a lecture and book signing by Paul Schofield, author of The Redeemer Reborn: Parsifal as the Fifth Opera of Wagner’s Ring. The audience members were so interested in what Mr. -

Remembering Music

lawrence m. zbikowski Remembering Music This article considers the role of memory in musical understanding through an exploration of some of the cognitive resources recruited for musical memory, with a special emphasis on processes of categorization and on the different memory systems which are brought to bear on musical phenomena. This perspective is then developed through a close analysis of the ways memory is exploited and expanded in To- ru Takemitsu’s Equinox, a short work for guitar written in 1993. Early in the second volume of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (translated as In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower) the narrator – having overcome a bit of awkwardness with Charles Swann – has become an intimate of Swann’s household, and the favored friend of his daughter Gilberte. On some days he joins the Swanns as they while away the afternoon at home, but on most occasions he joins them for a drive in the Bois de Boulogne. On occasion, before she changes her dress in preparation for their drive, Madame Swann sits down at the piano: The fingers of her lovely hands, emerging from the sleeves of her tea gown in crêpe de Chine, pink, white, or at times in brighter colors, wandered on the keyboard with a wistful- ness of which her eyes were so full, and her heart so empty. It was on one of those days that she happened to play the part of the Vinteuil sonata with the little phrase that Swann had once loved so much.1 This event provides Proust with an opportunity to reflect on the challenges of listening to music, and in particular on the difficulty of making something of a new piece on our first encounter with it. -

24. Debussy Pour Le Piano: Sarabande (For Unit 3: Developing Musical Understanding)

24. Debussy Pour le piano: Sarabande (For Unit 3: Developing Musical Understanding) Introduction and Performance circumstances Debussy probably decided to compose a Sarabande partly because he knew Erik Satie’s three sarabandes of 1887, with their similarly sensuous harmony. There are no grounds for referring to Debussy’s Sarabande as ‘impressionist’, even though the piece is very similar in date to his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. The term ‘neoclassical’ may be more suitable, although we do not hear the post-World War I type of ‘wrong-note’ neoclassicism of, for example, Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. In public performance Debussy’s Sarabande is most likely to be heard as part of a piano recital, along with the two other movements which flank it (Prélude and Toccata) from Pour le piano. Incidentally the suite was published in 1901, but the Sarabande (in a slightly different version to the one we know) dates back to 1894. Performing Forces and their Handling Sarabande, for solo piano, does not depend for its effect on any virtuosity or display. Marguerite Long, a pupil of Debussy, noted that the composer ‘himself played [the piece] as no one [else] could ever have done, with those marvellous successions of chords sustained by his intense legato’. A wide range is involved, from (several) very low C sharps to E just over five octaves higher; there are no extremely high notes. Some left-hand chords extend to well over an octave and have to be spread. Texture The texture is almost entirely homophonic, with much parallelism, and is often extremely sonorous on account of the many chords with six or more notes. -

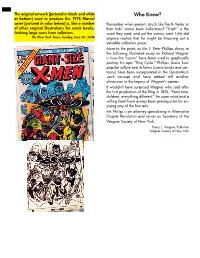

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production. -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France.