Hungarian Studies Review Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title Items-In-Visits of Heads of States and Foreign Ministers

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page Date 15/06/2006 Time 4:59:15PM S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Expanded Number S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Title items-in-Visits of heads of states and foreign ministers Date Created 17/03/1977 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0907-0001: Correspondence with heads-of-state 1965-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit •3 felt^ri ly^f i ent of Public Information ^ & & <3 fciiW^ § ^ %•:£ « Pres™ s Sectio^ n United Nations, New York Note Ko. <3248/Rev.3 25 September 1981 KOTE TO CORRESPONDENTS HEADS OF STATE OR GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERS TO ATTEND GENERAL ASSEMBLY SESSION The Secretariat has been officially informed so far that the Heads of State or Government of 12 countries, 10 Deputy Prime Ministers or Vice- Presidents, 124 Ministers for Foreign Affairs and five other Ministers will be present during the thirty-sixth regular session of the General Assembly. Changes, deletions and additions will be available in subsequent revisions of this release. Heads of State or Government George C, Price, Prime Minister of Belize Mary E. Charles, Prime Minister and Minister for Finance and External Affairs of Dominica Jose Napoleon Duarte, President of El Salvador Ptolemy A. Reid, Prime Minister of Guyana Daniel T. arap fcoi, President of Kenya Mcussa Traore, President of Mali Eeewcosagur Ramgoolare, Prime Minister of Haur itius Seyni Kountche, President of the Higer Aristides Royo, President of Panama Prem Tinsulancnda, Prime Minister of Thailand Walter Hadye Lini, Prime Minister and Kinister for Foreign Affairs of Vanuatu Luis Herrera Campins, President of Venezuela (more) For information media — not an official record Office of Public Information Press Section United Nations, New York Note Ho. -

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

Regime Stability and Foreign Policy Change Interaction Between Domestic and Foreign Policy in Hungary 1956-1994 Niklasson, Tomas

Regime Stability and Foreign Policy Change Interaction between Domestic and Foreign Policy in Hungary 1956-1994 Niklasson, Tomas 2006 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Niklasson, T. (2006). Regime Stability and Foreign Policy Change: Interaction between Domestic and Foreign Policy in Hungary 1956-1994. Department of Political Science, Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 REGIME STABILITY AND FOREIGN POLICY CHANGE Interaction between Domestic and Foreign Policy in Hungary 1956-1994 Tomas Niklasson Lund Political Studies 143 Department of Political Science Lund University Cover design: Cecilia Campbell Layout: Tomas Niklasson © 2006 Tomas Niklasson ISBN: 91-88306-56-9 Lund Political Studies 143 ISSN: 0460-0037 Printed by Studentlitteratur Lund, 2006 Distribution: Department of Political Science Lund University Box 52 SE-221 00 Lund SWEDEN http://www.svet.lu.se/lps/lps.html To Kasper and Felix, for the insights they have provided into work-life balance – and rat races.. -

Communism's Jewish Question

Communism’s Jewish Question Europäisch-jüdische Studien Editionen European-Jewish Studies Editions Edited by the Moses Mendelssohn Center for European-Jewish Studies, Potsdam, in cooperation with the Center for Jewish Studies Berlin-Brandenburg Editorial Manager: Werner Treß Volume 3 Communism’s Jewish Question Jewish Issues in Communist Archives Edited and introduced by András Kovács An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-041152-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041159-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041163-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover illustration: Presidium, Israelite National Assembly on February 20-21, 1950, Budapest (pho- tographer unknown), Archive “Az Izraelita Országos Gyűlés fényképalbuma” Typesetting: -

Kata Bohus History 2013

JEWS, ISRAELITES, ZIONISTS THE HUNGARIAN STATE’S POLICIES ON JEWISH ISSUES IN A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE (1956-1968) Kata Bohus A DISSERTATION in History Presented to the Faculties of the Central European University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013. Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. András Kovács Copyright in the text of this dissertation rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European University Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions and no materials previously written and/or published by another person unless otherwise noted. CEU eTD Collection 5 Abstract The dissertation investigates early Kádárism in Hungary, from the point of view of policies regarding Jewish issues, using a comparative framework of other Eastern European socialist countries. It follows state policies between 1956 and 1968, two dates that mark large Jewish emigration waves from communist Eastern Europe in the wake of national crises in Hungary (1956), Poland (1956, 1968) and Czechoslovakia (1968). The complex topic of policies relating to the Hungarian Jewish community, individuals of Jewish origin and the state of Israel facilitates the multidimensional examination of the post-Stalinist Party state at work. -

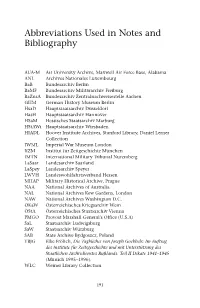

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Miskolc Journal of International Law Volume 4. (2007) No. 1

Miskolc Journal of International Law Kovács - Rogers - Nagy: Miskolc Journal of International Law Forgotten or Remembered? MISKOLCI NEMZETKÖZI JOGI KÖZLEMÉNYEK VOLUME 4. (2007) NO. 1. PP. 1-38. Péter Kovács1 - Jordan Thomas Rogers2 - Ernest A. Nagy3: Forgotten or Remembered? - The US Legation of Budapest and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 – (A virtual and annotated conversation with Jordan Thomas Rogers, Ernest A. Nagy and Géza Katona serving at the American Legation in Budapest in 1956) I. Péter Kovács’s Introduction – The antecedents of the project Some months ago, I wrote a short paper about diplomatic telegrams sent during the 1956 Revolution from the Budapest-based American, British and Soviet legations4. This article was based on two short booklets, containing a selection of diplomatic documents. „Secret reports”5 was published in 1989 and it contains British and American6 diplomatic telegrams sent from Budapest and some of the replies and instructions received respectively from London and Washington. The „Yeltsin-dossier”7 is the compilation of different documents8 transmitted by Boris Yeltsin in 1992 to Árpád Göncz, the Hungarian President of the Republic. In that 1 Péter Kovács is Judge at the Constitutional Court and Professor at the Faculty of Law of the Miskolc University and the Péter Pázmány Catholic University 2 Jordan Thomas Rogers is a former American diplomat who was between 1953-1957 at the American Legation in Budapest 3 Ernest A Nagy is also a former American diplomat who served at the American legation in Budapest between 1952-1956. 4 Péter Kovács: Understanding or Misunderstanding (About Diplomatic Telegrams sent from the American, British and Soviet Legations in Budapest between 23 October – 4 November 1956), Miskolc Journal of International Law, Vol 3(2006) N° 3 („1956 Hungary”) http://www.mjil.hu, pp. -

Ons Stad Nr 71

EDITORIAL Damals ie werden immer weniger, die Manner und Frauen, die Luxemburg und der Zweite Weltkrieg - das ist inzwischen sich noch ganz genau erinnern können an jene Zeit Geschichte. vor nunmehr über 60 Jahren, als die Souveränität unseres Die großartige Ausstellung "...et wor alles net esou kleinen Staates an einem Frühlingstag innerhalb von einfach" im Musée d'Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg, wenigen Stunden brutal vergewaltigt wurde, als die dank des großen Publikumserfolges - weit über deut-schePanzer die Schlagbäume der Grenzübergänge wie 22.000 Besucher wurden gezählt - bis zum 24. Streichhölzer umknickten und Luxemburg von den Nazis November 2002 verlängert wurde, hat jedoch eindrucks- "heim ins Reich" geholt werden sollte. voll bewiesen, dass auch heute noch bei breiten Die, die sich noch daran erinnern, als ob es gestern Bevölkerungsschichten ein starkes Interesse an diesem gewesen wäre, sie träumen immer noch von braunen Thema besteht. Uniformen, von Zügen, die sie in die Lager oder an die Die vorliegende Ons Stad-Nummer versucht, dieser verhasste Front brachten, wo sie auf der falschen Seite Tatsache Rechnung zu tragen. kämpfen mussten. Und wer offenen Auges durch die Stadt geht - das zeigt Sie erinnern sich an Umsiedlung und Angst, an Bomben u.a. der reich illustrierte Beitrag von Andre Hohengarten und Terror, an Standgerichte, an die Villa Pauly, an (S. 5-11), der findet sie auch heute noch überall, die deut-scheStraßennamen, an das Winterhilfswerk, an den Spuren und Zeugnisse aus einem düsteren Kapitel der Reichsarbeitsdienst, an die Gedelit und an den Gelben europäischen Geschichte. Stern, den die Juden an der Brust tragen mussten, ehe sie deportiert und vergast wurden. -

In Love with Life

IN LOVE WITH LIFE Edmond Israel IN LOVE WITH LIFE AN AMERICAN DREAM OF A LUXEMBOURGER Interviewed by Raymond Flammant Pampered child Refugee Factory worker International banker ——————— New Thinking SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY PRESS FAIRFIELD, CONNECTICUT 2006 IN LOVE WITH LIFE An American Dream of a Luxembourger by Edmond Israel ISBN 1-888112-13-1 Copyright 2006 by the Sacred Heart University Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact the Sacred Heart University Press, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, Connecticut 06825-1000. This book is based on La vie, passionnément Entretiens avec Raymond Flammant French edition published in 2004 by Editions Saint Paul, Luxembourg I dedicate these pages to all those who brought light and warmth to my life. I thank my dear wife Renée for her counsel and advice. I express my particular appreciation to Raymond Flammant, who asked me the right questions. Thanks also to my assistant, Suzanne Cholewka Pinai, for her efficient help. Contents Foreword by Anthony J. Cernera ix Preface xiii Part One / DANCING ON A VOLCANO 1. Pampered Child 3 The Roaring Twenties in Europe 3 Cocooning in the family fold 8 School and self-education 14 The first signs of a devastating blaze 23 The dilemma: die or die in trickles? 27 The “Arlon” plan 30 Part Two / SURVIVING, LIVING, CONSTRUCTING 2. Refugee 35 The rescue operation “Arlon” 35 Erring on the roads of France 38 Montpellier or “The symphony in black” 40 Marseille: a Scottish shower and men with a big heart 43 The unknown heroes of Gibraltar 48 From Casablanca to the shores of liberty 49 viii / CONTENTS 3. -

Zweete Weltkrich

D'Occupatioun Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich 75 Joer Liberatioun Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich 75 Joer Liberatioun 75 Joer Fräiheet! 75 Joer Fridden! 5 Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich. 75 Joer Liberatioun 7 D'Occupatioun 10 36 Conception et coordination générale Den Naziregime Dr. Nadine Geisler, Jean Reitz Textes Dr. Nadine Geisler, Jean Reitz D'Liberatioun 92 Corrections Dr. Sabine Dorscheid, Emmanuelle Ravets Réalisation graphique, cartes 122 cropmark D'Ardennenoffensiv Photo couverture Photothèque de la Ville de Luxembourg, Tony Krier, 1944 0013 20 Lëtzebuerg ass fräi 142 Photos rabats ANLux, DH-IIGM-141 Photothèque de la Ville de Luxembourg, Tony Krier, 1944 0007 25 Remerciements 188 Impression printsolutions Tirage 800 exemplaires ISBN 978-99959-0-512-5 Editeur Administration communale de Pétange Droits d’auteur Malgré les efforts de l’éditeur, certains auteurs et ayants droits n’ont pas pu être identifiés ou retrouvés. Nous prions les auteurs que nous aurons omis de mentionner, ou leurs ayants droit, de bien vouloir nous en excuser, et les invitons à nous contacter. Administration communale de Pétange Place John F. Kennedy L-4760 Pétange page 3 75 Joer Fräiheet! 75 Joer Fridden! Ufanks September huet d’Gemeng Péiteng de 75. Anniversaire vun der Befreiung gefeiert. Eng Woch laang gouf besonnesch un deen Dag erënnert, wou d’amerikanesch Zaldoten vun Athus hir an eist Land gefuer koumen. Et kéint ee soen, et wier e Gebuertsdag gewiescht, well no véier laange Joren ënner der Schreckensherrschaft vun engem Nazi-Regime muss et de Bierger ewéi en neit Liewe virkomm sinn. Firwat eng national Ausstellung zu Péiteng? Jo, et gi Muséeën a Gedenkplazen am Land, déi un de Krich erënneren. -

1961–1963 First Supplement

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY NATIONAL SECURITY FILES USSRUSSR ANDAND EASTERNEASTERN EUROPE:EUROPE: NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961–1963 FIRST SUPPLEMENT A UPA Collection from National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 USSR and Eastern Europe First Supplement Microfilmed from the Holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Nicholas P. Cunningham A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road • Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. USSR and Eastern Europe. First supplement [microform] / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels ; 35 mm. — (National security files) “Microfilmed from the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts.” Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Nicholas P. Cunningham. ISBN 1-55655-876-7 1. United States—Foreign relations—Soviet Union—Sources. 2. Soviet Union—Foreign relations—United States—Sources. 3. United States—Foreign relations—1961–1963— Sources. 4. National security—United States—History—Sources. 5. Soviet Union— Foreign relations—1953–1975—Sources. 6. Europe, Eastern—Foreign relations—1945– 1989. I. Lester, Robert. II. Cunningham, Nicholas P. III. University Publications of America (Firm) IV. Title. V. Series. E183.8.S65 327.73047'0'09'046—dc22 2005044440 CIP Copyright © 2006 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-876-7. -

The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933- 1945

THE FUNCTION OF SELECTION IN NAZI POLICY TOWARDS UNIVERSITY STUDENTS 1933- 1945 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial hlfillment of the requirernents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History York University North York, Ontario December 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogaphic Services se~cesbibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your tlk Votre refénmce Our fi& Notre refdrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or elecîronic formats. la forme de microfiche/tilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in ths thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Towards a New Genus of Students: The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933-1945 by Béla Bodo a dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of York University in partial fulfillment of the requirernents for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Permission has been granted to the LIBRARY OF YORK UNlVERSlrY to lend or seIl copies of this dissertation, to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA to microfilm this dissertation and to lend or sel1 copies of the film.