In Love with Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

National Public Radio's “This I Believe”

Letter from the Editor Airing Beliefs: National Public Radio’s “This I Believe” effervescent news for everyone A recent study by Harvard social scientists found that violence appears to work like an infection – a fizz Show, Past and Present by Alexis Burling contagious disease (Science. May 27, 2005). They evaluated a group of teens at three different points in mission The mission of Fizz is to create a space in which their adolescence, and applied rigorous control in their analysis to ensure that all potentially confounding to find the future today, by focusing on endeavors factors were omitted (153 variables were included). According to their findings, witnessing gun violence that are of permanent value and that hold essential after the original, the new version of This I more than doubled the risk that a teen would themselves commit some similar violent act. The risk associ- seeds of change within. “We hardly need to be reminded that we are living in an age of confusion – a lot of us have Believe differs from its predecessor in a few minor respects. The new version airs weekly ated with witnessing gun violence was overwhelmingly greater than that associated with poverty, drug use, people traded in our beliefs for bitterness and cynicism or for a heavy package of despair, or even a instead of daily, and is integrated into already and family situation. editor-in-chief Jessica Wapner quivering portion of hysteria. Opinions can be picked up cheap in the market place while design and layout Hiram Pines established programs, Morning Edition or All such commodities as courage and fortitude and faith are in alarmingly short supply…What A study like that causes so many questions. -

NSK REPORT 2019 Year Ended March 31, 2019 Integrated Report NSK REPORT 2019

NSK REPORT 2019 Year ended March 31, 2019 Integrated Report NSK REPORT 2019 NSK used environmentally friendly paper and printing methods for this publication. CAT. No. E8412 2019 B-10 Printed in Japan @NSK Ltd. 2019 Mission Statement NSK contributes to a safer, smoother society and NSK’s Value Creation Story helps protect the global environment through Vision TM its innovative technology integrating Motion & Control . We formulated NSK Vision 2026 to mark As a truly international enterprise, we are working across national the 100th anniversary of our foundation boundaries to improve relationships between people throughout the world. in 2016, aiming to create new value over the next decade. Origin Sustainability Management Principles Action Guidelines Mission Over the 100 years since its Promote ESG Management 1 To provide our customers with Beyond Limits, Beyond Today innovative and responsive Statement foundation in 1916, NSK has taken NSK’s Value Created Placing“ safety,”“ quality,” solutions through our world on the challenge of developing Beyond Frontiers “compliance,” and“ environment” leading technologies. innovative technologies as Japan’s Environmental contribution Customers (low friction, high efficiency, Employees as core values, NSK will help find Beyond Individuals first bearing manufacturer and improvement of transmission efficiency) 2 To provide challenges and solutions to social issues by opportunities to our employees, has supported the development Contribution to an advanced technological society utilizing their skills and Management Principles / Beyond Imagination of industries worldwide while realizing value co-creation as it encouraging their creativity and meets the expectations of Action Guidelines Beyond Perceptions contributing to the reduction of Realization of a more prosperous society Local individuality. -

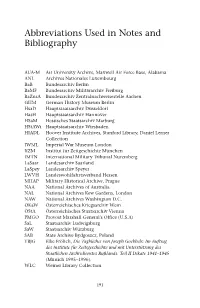

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Ons Stad Nr 71

EDITORIAL Damals ie werden immer weniger, die Manner und Frauen, die Luxemburg und der Zweite Weltkrieg - das ist inzwischen sich noch ganz genau erinnern können an jene Zeit Geschichte. vor nunmehr über 60 Jahren, als die Souveränität unseres Die großartige Ausstellung "...et wor alles net esou kleinen Staates an einem Frühlingstag innerhalb von einfach" im Musée d'Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg, wenigen Stunden brutal vergewaltigt wurde, als die dank des großen Publikumserfolges - weit über deut-schePanzer die Schlagbäume der Grenzübergänge wie 22.000 Besucher wurden gezählt - bis zum 24. Streichhölzer umknickten und Luxemburg von den Nazis November 2002 verlängert wurde, hat jedoch eindrucks- "heim ins Reich" geholt werden sollte. voll bewiesen, dass auch heute noch bei breiten Die, die sich noch daran erinnern, als ob es gestern Bevölkerungsschichten ein starkes Interesse an diesem gewesen wäre, sie träumen immer noch von braunen Thema besteht. Uniformen, von Zügen, die sie in die Lager oder an die Die vorliegende Ons Stad-Nummer versucht, dieser verhasste Front brachten, wo sie auf der falschen Seite Tatsache Rechnung zu tragen. kämpfen mussten. Und wer offenen Auges durch die Stadt geht - das zeigt Sie erinnern sich an Umsiedlung und Angst, an Bomben u.a. der reich illustrierte Beitrag von Andre Hohengarten und Terror, an Standgerichte, an die Villa Pauly, an (S. 5-11), der findet sie auch heute noch überall, die deut-scheStraßennamen, an das Winterhilfswerk, an den Spuren und Zeugnisse aus einem düsteren Kapitel der Reichsarbeitsdienst, an die Gedelit und an den Gelben europäischen Geschichte. Stern, den die Juden an der Brust tragen mussten, ehe sie deportiert und vergast wurden. -

Zweete Weltkrich

D'Occupatioun Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich 75 Joer Liberatioun Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich 75 Joer Liberatioun 75 Joer Fräiheet! 75 Joer Fridden! 5 Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich. 75 Joer Liberatioun 7 D'Occupatioun 10 36 Conception et coordination générale Den Naziregime Dr. Nadine Geisler, Jean Reitz Textes Dr. Nadine Geisler, Jean Reitz D'Liberatioun 92 Corrections Dr. Sabine Dorscheid, Emmanuelle Ravets Réalisation graphique, cartes 122 cropmark D'Ardennenoffensiv Photo couverture Photothèque de la Ville de Luxembourg, Tony Krier, 1944 0013 20 Lëtzebuerg ass fräi 142 Photos rabats ANLux, DH-IIGM-141 Photothèque de la Ville de Luxembourg, Tony Krier, 1944 0007 25 Remerciements 188 Impression printsolutions Tirage 800 exemplaires ISBN 978-99959-0-512-5 Editeur Administration communale de Pétange Droits d’auteur Malgré les efforts de l’éditeur, certains auteurs et ayants droits n’ont pas pu être identifiés ou retrouvés. Nous prions les auteurs que nous aurons omis de mentionner, ou leurs ayants droit, de bien vouloir nous en excuser, et les invitons à nous contacter. Administration communale de Pétange Place John F. Kennedy L-4760 Pétange page 3 75 Joer Fräiheet! 75 Joer Fridden! Ufanks September huet d’Gemeng Péiteng de 75. Anniversaire vun der Befreiung gefeiert. Eng Woch laang gouf besonnesch un deen Dag erënnert, wou d’amerikanesch Zaldoten vun Athus hir an eist Land gefuer koumen. Et kéint ee soen, et wier e Gebuertsdag gewiescht, well no véier laange Joren ënner der Schreckensherrschaft vun engem Nazi-Regime muss et de Bierger ewéi en neit Liewe virkomm sinn. Firwat eng national Ausstellung zu Péiteng? Jo, et gi Muséeën a Gedenkplazen am Land, déi un de Krich erënneren. -

The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933- 1945

THE FUNCTION OF SELECTION IN NAZI POLICY TOWARDS UNIVERSITY STUDENTS 1933- 1945 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial hlfillment of the requirernents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History York University North York, Ontario December 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogaphic Services se~cesbibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your tlk Votre refénmce Our fi& Notre refdrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or elecîronic formats. la forme de microfiche/tilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in ths thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Towards a New Genus of Students: The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933-1945 by Béla Bodo a dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of York University in partial fulfillment of the requirernents for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Permission has been granted to the LIBRARY OF YORK UNlVERSlrY to lend or seIl copies of this dissertation, to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA to microfilm this dissertation and to lend or sel1 copies of the film. -

Ettelbrück 1940-45 Sankt Anna Und Der Krieg

Ettelbrück 1940-45 Sankt Anna und der Krieg Inhalt Vorwort 1. Der Bericht 2. Das Pensionat 3. Der Kriegsverlauf 4. Sankt Anna im Krieg Vorwort Als Mitglied des Netzwerks der UNESCO-Schulen war es für die Privatschule Sainte-Anne selbstverständlich an dem Projekt „Rucksakbibliothéik“ teilzunehmen. Gilt es als Bildungsanstalt zwar vor allem die Jugendlichen auf eine sich immer schneller verändernde ZukunK vorzubereiten, so darf der Blick in die Ver- gangenheit jedoch nicht zu kurz kommen. Seit Jahren bemühen wir uns, unsere Schülerinnen projektorienOert an der Aufar- beitung der Vergangenheit teilnehmen zu lassen und ihnen so die Geschichte greiParer und verständlicher werden zu lassen. Die Teilnahme an Gedenkzeremonien, die jährlichen Studien- reisen, die Zeitzeugenbesuche sowie die SensibilisierungsakOo- nen an den Gedenktagen sind fest im Schulgeschehen verankert. Dieses E-Book über die Geschichte des Pensionats im 2. Weltkrieg verbindet viele Anliegen, die unserer Schulgemein- schaK wichOg sind. Erstens ist es schülerorienOert, denn gemein- sam wurde am Text gefeilt und geforscht, um ein Produkt zu er- stellen, das für heuOge Jugendliche gut verständlich ist. Gle- ichzeiOg stellt es eine Auseinandersetzung mit den neuen Medi- en dar. Das Digitalisieren, Verarbeiten und Gestalten des Buches wurde miVels neuer Medien, die immer mehr zu den Kernkom- petenzen des Alltags gehören, ausgeführt. Und schließlich wer- den durch dieses Buch die Werte unserer SchulgemeinschaK bestäOgt. Der Zusammenhalt und der respektvolle Umgang in unserer Schule basiert auf einer langen TradiOon und werden auch in ZukunK hochgehalten. Allen Schülerinnen und Lehrer/innen, die am Projekt beteiligt waren, gilt mein aufrichOger Dank. Nun aber wird es Zeit in die bewegte Vergangenheit unserer SchulgemeinschaK einzu- tauchen. -

Social Science Department Freshmen World History May 25-29 Greetings

Social Science Department Freshmen World History May 25-29 Greetings Freshmen World Students! We hope you are safe and well with your families! Below is the lesson plan for this week: Content Standard: Topic 4. The Great Wars, 1914–1945 [WHII.T4] Supporting Question: What were the causes and consequences of the 20th century’s two world wars? 1. Analyze the effects of the battles of World War II on the outcome of the war and the countries involved; 14. Analyze the decision of the United States to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in order to bring the war with Japan to a swift conclusion and its impact on relations with the Soviet Union. Practice Standard(s): 2. Organize information and data from multiple primary and secondary sources. 3. Argue or explain conclusions, using valid reasoning and evidence. 5. Evaluate the credibility, accuracy and relevance of each source. 6. Argue or explain conclusions, using valid reasoning and evidence. Weekly Learning Opportunities: • World War II Events/Battles: Readings & Questions • Video Clip & Viewing Guide • World War II: Visual Analysis • Primary Source Activity: Life as an RAF Pilot • Compare and Contrast: Graph Activity Long Term Opportunities: • Atomic Bomb DBQ Additional Resources: • Greatest Events of WWII In Colour (Netflix) • Newsela: World War II: Content Text Set • Newsela: World War II: Supplemental Text Set Note to students: Your Social Science teacher will contact you with specifics regarding the above assignments in addition to strategies and recommendations for completion. Please email your teacher with specific questions and/or contact during office hours. WWII Events/ Battles: Week of 5/25 Massachusetts History Framework: Content Standard: Topic 4. -

National Foreign Policy Conference for Editors and Broadcasters

OPENING REMARKS VICE PRES I DENT HUBERT H. HUMPHREY DEPARTMENT OF STATE NATIONAL FOREIGN POLl CY CONFERENCE FOR EDITORS AND BROADCASTERS APRIL 28, 1966 I am delighted to have the opportunity of spending some time today with so many of the people who do so much to make the American people the best informed public in the world. The fact that several hundred of you, from all parts of the country, have gone to the trouble and expense to be here today testifies to the seriousness with which you view your res(X>nsibilities. -2- It indicates the attention which all Americans today are giving to the world around them. I agree with President Eisenhower that "what we ca I foreign affairs is no longer foreign affairs; it's a local affair. Whatever happens in Indonesia is important to Indiana • • • • We can not escape each other." For two decades the power and purpose of the United States have helped contain totalitarian expansion around the world. But this has not been our only aim. We have, in President Kennedy's phrase, sought ''to make the world safe for diversity" ••• to make Slf e that no one nation or group of nations ever gains the right to define world order, let alone to manage it. But diversity must , in this nuclear age, be accompanied by safety. -3- The threat to both diversity and safety in post-war Europe was clear and visible. Today -- in large part because of the success of our post-war policies -- the threat to Europe has receded. There are still threats to diversity and safety in the world, but they are not so simple and direct as was the post-war challenge in Europe. -

The Westie Connection

West Haven High School Library Media/Technology Center The Westie Connection June 2015 Volume 4, Issue 3 THIS I BELIEVE. ONE BOOK. ONE COMMUNITY. "A welcome change from the sloganeering, political mudslinging and products of spin doctors."--The Philadelphia Inquirer The book, This I Believe, is based on the NPR series of the same name. All different Americans--from the famous to the unknown--write short passages connecting to the original thought as the title of the book suggests. This book will make teachers and students reflect on their own beliefs. Featuring many renowned contributors-- including Jackie Robinson, Colin Powell, Gloria Steinem, Albert Einstein, Penn Jil- lette, Bill Gates, and John Updike-- The American Spirit at its best. One book. One community. For further information and to sign up to receive the I Believe Newsletter via email: WEBSITE: http://thisibelieve.org This I Believe, Inc. [[email protected]] Celebrating Four Years Of 'This I Believe' April 27, 2009 • During its four-year run on NPR, This I Believe engaged listeners in a discussion of the core beliefs that guide their daily lives. We heard from people of all walks of life — the very young and the very old, the famous and the previously unknown. This I Believe was a five-minute CBS Radio Network program hosted by journalist Edward R. Murrow from 1951 to 1955. A half-hour European version of This I Believe ran from 1956 to 1958 over Radio Luxembourg. Newsletter composed by: The show encouraged both famous and everyday people to write short essays about their own personal Marilyn Lynch, motivation in life and then read them on the air. -

Iagg Newsletter Seoul, December 2015 Vol

IAGG NEWSLETTER SEOUL, DECEMBER 2015 VOL. 20 / NO.9 02 IAGG HEADQUARTERS 04 IAGG REGIONAL NEWS 07 IAGG'S SUB-ORGANIZATIONS 12 UN ACTIVITIES 15 NATIONAL MEMBER SOCIETIES 22 UPCOMING EVENTS 23 OTHERS IAGG HEADQUARTERS IAGG ASIA/OCEANIA REGIONAL CONGRESS, CHIANG MAI, THAILAND, OCTOBER 19-22, 2015 The 10th IAGG Asia/Oceania Regional Congress was held in Chiang Mai, Thailand at the International Convention and Exhibition Center from October 19-22, 2015, under the theme of Healthy Ageing Beyond Frontiers. The regional congress, which is held every four years, was an opportunity for many well-known gerontologists, geriatrics scholars, policy decision-makers, professional activists, related companies and researchers to get together and share recent discoveries and study results. Prof. Heung Bong CHA, IAGG President and Prof. Sung Jae CHOI, IAGG Secretary-General and Prof. Dong Ho LEE, IAGG Treasurer attended the congress where Prof. CHA delivered an opening speech and Prof. CHOI gave a presentation on “Active Ageing in Korea” as invited speaker. 12TH WORLD CONGRESS ON LONG TERM CARE IN CHINESE COMMUNITIES 2 IAGG HEADQUARTERS In view of the rapid trend in population aging and exigency of long-term care services development, the World Congress on Long Term Care in Chinese Communities has been held since 2002 in cities including Hong Kong (2002, 2011), Taipei (2004, 2009), Shanghai (2005, 2010), Macau (2006, 2013), Beijing (2007), Hangzhou (2012), and Ningpo (2014), successfully establishing a platform for in-depth multidisciplinary discussion and communication. The Twelfth World Congress on Long Term Care in Chinese Communities was held in Taiwan on the 30th November to 2nd December, 2015.