The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933- 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPONYMS in DERMATOLOGY LITERATURE LINKED to GENITAL SKIN DISORDERS Khalid Al Aboud1, Ahmad Al Aboud2

Historical Article DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20132.60 EPONYMS IN DERMATOLOGY LITERATURE LINKED TO GENITAL SKIN DISORDERS Khalid Al Aboud1, Ahmad Al Aboud2 1Department of Public Health, King Faisal Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia Source of Support: 2Dermatology Department, King Abdullah Medical City, Makkah, Saudi Arabia Nil Competing Interests: None Corresponding author: Dr. Khalid Al Aboud [email protected] Our Dermatol Online. 2013; 4(2): 243-246 Date of submission: 24.09.2012 / acceptance: 04.11.2012 Cite this article: Khalid Al Aboud, Ahmad Al Aboud: Eponyms in dermatology literature linked to genital skin disorders. Our Dermatol Online. 2013; 4(2): 243-246. There are numerous eponymous systemic diseases which of Nazi party membership, forced human experimentation may affect genital skin or sexual organs in both genders. For in the Buchenwald concentration camp, and subsequent example Behçet disease which is characterized by relapsing prosecution in Nuremberg as a war criminal, have come to oral aphthae, genital ulcers and iritis. light. This disease is named after Hulusi Behçet [1] (1889–1948), One more example is syphilis. In 1530, the name „syphilis” (Fig. 1), the Turkish dermatologist and scientist who was first used by the Italian physician and poet Girolamo first recognized the syndrome. This disease also called Fracastoro [4] (1478-1553), as the title of his Latin poem „Adamantiades’ syndrome” or „Adamandiades-Behçet in dactylic hexameter describing the ravages of the disease syndrome”, for the work done by Benediktos Adamantiades. in Italy. In his well-known poem „Syphilidis sive de morbo Benediktos Adamantiades (1875-1962), (Fig. 2) was a Greek gallico libri tres” (Three books on syphilis or the French ophthalmologist [2]. -

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

Tangled Complicities and Moral Struggles: the Haushofers, Father and Son, and the Spaces of Nazi Geopolitics

Journal of Historical Geography 47 (2015) 64e73 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Historical Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg Feature: European Geographers and World War II Tangled complicities and moral struggles: the Haushofers, father and son, and the spaces of Nazi geopolitics Trevor J. Barnes a,* and Christian Abrahamsson b a Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, 1984 West Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z2, Canada b Department of Sociology and Human Geography, University of Oslo, Postboks 1096 Blindern, Oslo 0317, Norway Abstract Drawing on a biographical approach, the paper explores the tangled complicities and morally fraught relationship between the German father and son political geographers, Karl and Albrecht Haushofer, and the Nazi leadership. From the 1920s both Haushofers were influential within Nazism, although at different periods and under different circumstances. Karl Haushofer’s complicity began in 1919 with his friendship with Rudolf Hess, an undergraduate student he taught political geography at the University of Munich. Hess introduced Haushofer to Adolf Hitler the following year. In 1924 Karl provided jail-house instruction in German geopolitical theory to both men while they served an eight-and-a-half month prison term for treason following the ‘beer-hall putsch’ of November 1923. Karl’s prison lectures were significant because during that same period Hitler wrote Mein Kampf. In that tract, Hitler justifies German expansionism using Lebensraum, one of Haushofer’s key ideas. It is here that there is a potential link between German geopolitics and the subsequent course of the Second World War. Albrecht Haushofer’s complicity began in the 1930s when he started working as a diplomat for Joachim von Ribbentrop in a think-tank within the Nazi Foreign Ministry. -

III. Zentralismus, Partikulare Kräfte Und Regionale Identitäten Im NS-Staat Michael Ruck Zentralismus Und Regionalgewalten Im Herrschaftsgefüge Des NS-Staates

III. Zentralismus, partikulare Kräfte und regionale Identitäten im NS-Staat Michael Ruck Zentralismus und Regionalgewalten im Herrschaftsgefüge des NS-Staates /. „Der nationalsozialistische Staat entwickelte sich zu einem gesetzlichen Zentralismus und zu einem praktischen Partikularismus."1 In dürren Worten brachte Alfred Rosen- berg, der selbsternannte Chefideologe des „Dritten Reiches", die institutionellen Unzu- länglichkeiten totalitärer Machtaspirationen nach dem „Zusammenbruch" auf den Punkt. Doch öffnete keineswegs erst die Meditation des gescheiterten „Reichsministers für die besetzten Ostgebiete"2 in seiner Nürnberger Gefängniszelle den Blick auf die vielfältigen Diskrepanzen zwischen zentralistischem Herrschafts<*«s/>r«c/> und fragmen- tierter Herrschaftspraus im polykratischen „Machtgefüge" des NS-Regimes3. Bis in des- sen höchste Ränge hinein hatte sich diese Erkenntnis je länger desto mehr Bahn gebro- chen. So beklagte der Reichsminister und Chef der Reichskanzlei Hans-Heinrich Lammers, Spitzenrepräsentant der administrativen Funktionseliten im engsten Umfeld des „Füh- rers", zu Beginn der vierziger Jahre die fortschreitende Aufsplitterung der Reichsver- waltung in eine Unzahl alter und neuer Behörden, deren unklare Kompetenzen ein ge- ordnetes, an Rationalitäts- und Effizienzkriterien orientiertes Verwaltungshandeln zuse- hends erschwerten4. Der tiefgreifenden Frustration, welche sich der Ministerialbürokra- tie ob dieser Zustände bemächtigte, hatte Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg schon 1 Alfred Rosenberg, Letzte Aufzeichnungen. Ideale und Idole der nationalsozialistischen Revo- lution, Göttingen 1955, S.260; Hervorhebungen im Original. Vgl. dazu Dieter Rebentisch, Führer- staat und Verwaltung im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Verfassungsentwicklung und Verwaltungspolitik 1939-1945, Stuttgart 1989, S.262; ders., Verfassungswandel und Verwaltungsstaat vor und nach der nationalsozialistischen Machtergreifung, in: Jürgen Heideking u. a. (Hrsg.), Wege in die Zeitge- schichte. Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Gerhard Schulz, Berlin/New York 1989, S. -

DIE MITARBEITER DES BANDES Prof. Dr. Werner T. Angress, Dept. Of

DIE MITARBEITER DES BANDES Prof. Dr. Werner T. Angress, Dept. of History, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, Ν. Y. 11794, USA Dr. Wilhelm Arenz, Von-Schnewling-Weg 6, 7812 Bad Krozingen Dr. Walther L. Bernecker, Akademischer Rat, Ziehrerstr. 7 a, 8906 Gersthofen Edda Bilger, Μ. Α., 417 Ν. Donaldson, Stillwater, Oklahoma 74074, USA Prof. Dr. Fritz Blaich, Lehrstuhl für Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Universität Regensburg, 8400 Regens- burg Dr. Rainer A. Blasius, Hardt 43, 4018 Langenfeld Dr. Brian Bond, Dept. of War Studies, University of London King's College, Strand, London, W. C. 2, United Kingdom Dr. Heinz-Ludger Borgert, Archivrat im Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv, Freiburg i. Br., Alemannen- straße 11, 7809 Denzlingen Prof. Dr. Martin van Creveld, Dept. of History, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem Dr. Gerald H. Davis, Professor of History, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Ga. 30303, USA Dr. Wilhelm Deist, Ltd. Wiss. Direktor, Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt Dr. Η. R. Delporte, Wiss. Direktor a.D., Sundgauallee 55, 7800 Freiburg i.Br. Prof. Dr. Jost Diilffer, Hist. Seminar der Universität Köln, Albertus-Magnus-Platz, 5000 Köln 41 Prof. Dr. Alexander Fischer, Hist. Seminar/Abt. Osteuropäische Geschichte der Johann-Wolfgang- Goethe-Universität, Senckenberganlage 31, 6000 Frankfurt a. M. 1 Johannes Fischer, Oberst a.D., Sonnenwiese 10, 7803 Gundelfingen-Wildtal Dr. Roger Fletcher, 11/26—28 Park Avenue, Burwood 2134, Australia Dr. Jürgen Förster, Wiss. Oberrat, Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt Dr. Friedrich Forstmeier, Kapitän z.S. a.D., Alemannenstr. 57, 7800 Freiburg i.Br. Prof. Dr. Konrad Fuchs, Hist. Seminar der Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Saarstr. 21, 6500 Mainz Prof. Dr. Hans W. -

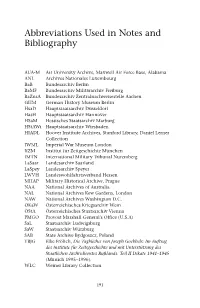

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Incidence of Reactive Arthritis & Other Musculoskeletal Sequelae of Enteric Bacterial Infection in Oregon: a Population-Base

10/29/2013 Oregon Health & Science University Wins the Knowledge Bowl ACR 2013: Go Portlandumabs!! REACTIVE ARTHRITIS IN 2013: WHAT HAVE WE LEARNT? Atul Deodhar MD Professor of Medicine Division of Arthritis & Rheumatic Diseases Oregon Health & Science University Portland, OR Disclosures Evidence-Based Medicine 1. Townes JM, Deodhar AA, Smith K, et al. Rheumatologic • Honoraria, Advisory Boards: Abbvie, MSD, Novartis, Sequelae of Enteric Bacterial Infection in Minnesota and Pfizer, UCB Oregon: A Population-based Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1689-96. • Research Grants: Abbvie, Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB 2. On the difficulties of establishing a consensus on the definition of and diagnostic investigations for reactive arthritis. Results and discussion of a questionnaire prepared for the 4th International Workshop on Reactive Arthritis, Berlin, Germany, July 3-6, 1999.Braun J. et al. J Rheumatol. 2000 Sep;27(9):2185-92. 3. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo in the treatment of reactive arthritis (Reiter's syndrome). A Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Clegg DO. et al. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 Dec;39(12):2021- 7. What is Reactive Arthritis? Reactive Arthritis • “Arthritis associated with demonstrable infection at a distant site without traditional evidence of sepsis at the affected joint(s)” Andrew Keat, Adv Exp Med Biol 1999;455:201-6 • Classical Pathogens : Chlamydia trachomatis, Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella & Campylobacter (perhaps Clostridium difficile, Chlamydia pneumoniae & BCG instillation in bladder) • Interval -

Luise Haus',Intro

Introduction The Haushofers And The Nazis Luise Haushofer’s Jail Journal follows on from Albrecht Haushofer’s Moabite Sonnets, a bilingual edition of which appeared in 2001 with an introduction about the Haushofers, Geopolitics and the Second World War. Luise (née Renner) was Albrecht’s sister-in-law. After Moabite Sonnets appeared, her daughter—Andrea Haushofer-Schröder, Albrecht’s niece—contacted me and gave me some documents which illustrate the family consequences of Albrecht’s resistance activities. One of these was that Luise served time in jail as the Gestapo suspected her of helping Albrecht to elude capture after the 20th July 1944—a phrase which is shorthand for the attempt to assassinate Hitler and establish an alternative Government that would attempt to negotiate an end to the Second World War, and re-establish democracy in Germany. Because of the Nazi policy of Sippenhaft— arresting the family of an accused—Albrecht landed the Renner as well as the Haushofer families in trouble with the Gestapo and caused some dispute and ill- feeling between the two. The documents Andrea gave me appear here in the original German and in English translation. They comprise a communication from Martha Haushofer to Anna Renner; another from Karl Haushofer to Paul Renner; a reply from Renner; and a surviving fragment of a Jail Journal written by Luise Haushofer in 1963. In addition, there are several illustrations from the Haushofer archive (provided by Andrea). Albrecht was summarily executed in the closing hours of the War for his part in the Resistance to the Hitler regime. He had been captured in December 1944 and kept on ice in the Berlin Moabite Prison by the Nazis, in case his English contacts would be useful in the event of a negotiated end to the war. -

Ons Stad Nr 71

EDITORIAL Damals ie werden immer weniger, die Manner und Frauen, die Luxemburg und der Zweite Weltkrieg - das ist inzwischen sich noch ganz genau erinnern können an jene Zeit Geschichte. vor nunmehr über 60 Jahren, als die Souveränität unseres Die großartige Ausstellung "...et wor alles net esou kleinen Staates an einem Frühlingstag innerhalb von einfach" im Musée d'Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg, wenigen Stunden brutal vergewaltigt wurde, als die dank des großen Publikumserfolges - weit über deut-schePanzer die Schlagbäume der Grenzübergänge wie 22.000 Besucher wurden gezählt - bis zum 24. Streichhölzer umknickten und Luxemburg von den Nazis November 2002 verlängert wurde, hat jedoch eindrucks- "heim ins Reich" geholt werden sollte. voll bewiesen, dass auch heute noch bei breiten Die, die sich noch daran erinnern, als ob es gestern Bevölkerungsschichten ein starkes Interesse an diesem gewesen wäre, sie träumen immer noch von braunen Thema besteht. Uniformen, von Zügen, die sie in die Lager oder an die Die vorliegende Ons Stad-Nummer versucht, dieser verhasste Front brachten, wo sie auf der falschen Seite Tatsache Rechnung zu tragen. kämpfen mussten. Und wer offenen Auges durch die Stadt geht - das zeigt Sie erinnern sich an Umsiedlung und Angst, an Bomben u.a. der reich illustrierte Beitrag von Andre Hohengarten und Terror, an Standgerichte, an die Villa Pauly, an (S. 5-11), der findet sie auch heute noch überall, die deut-scheStraßennamen, an das Winterhilfswerk, an den Spuren und Zeugnisse aus einem düsteren Kapitel der Reichsarbeitsdienst, an die Gedelit und an den Gelben europäischen Geschichte. Stern, den die Juden an der Brust tragen mussten, ehe sie deportiert und vergast wurden. -

(1!~,1'/~ '--L Robert S

May 5, 1964 As director of this Senior Thesis, I recommend that it be accepted in fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors. (1!~,1'/~ '--l Robert s. Sears Associate Professor Foreign Language THEMES OF RESIGNArrI()N AND PF.SSTMISM IN AI~RECHT HA.USHOFER' 8 MO~:B.I 'Tlf.:3 ~.Ql.!~~.1'1? THEMES OF RESIGNATION AND P1':SSIMISM IN ALBRECHT HAUSHOFER'S ¥O~~ITER SONE~~E A RESEARCH P.4.PRR SUBMITTED TO THE HONORS COMMITTEE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree BACHELOR OF ARTS "VITH HONORS by LINDA MAPJE HANOOCK ADVISER - ROBERT SEARS BALL STATE TEACHERS COLLBGE MUNCIE, INDIANA. MAY. lq64 ! , " .' , DANKE SCHOEN an Her:rn Sears, who took the blame for m,?ny of my failures, and al:3o Drs. Rippy and MacGi bbon for "fachliche Rilfe." NOTES: where material was duplicated in several sources, it is footnoted as having come from one book, generally the one in which the best, most detailed, and most comprehensive coverage of the material was found, which sometimes results in what appears to be a preponderance of fl"lotnotes from only OIle source, due to the sonnets having been reprinted in fragments in variouEI articiles, all sonnets Quoted are documented as though their source were the book MO ABITER ~(YN~TrrE and not the individual a,..ticle in which thev anpeared. Spellin,Q" however has been Anglicized due to the difficulty in reproducing German diacritical markings. althou~~ criticism was translated from the German when quoted, the sonnets were lp-ft intact to p~eserve the effect that would h~ve been lost by an inadequate rennering into English. -

In Love with Life

IN LOVE WITH LIFE Edmond Israel IN LOVE WITH LIFE AN AMERICAN DREAM OF A LUXEMBOURGER Interviewed by Raymond Flammant Pampered child Refugee Factory worker International banker ——————— New Thinking SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY PRESS FAIRFIELD, CONNECTICUT 2006 IN LOVE WITH LIFE An American Dream of a Luxembourger by Edmond Israel ISBN 1-888112-13-1 Copyright 2006 by the Sacred Heart University Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact the Sacred Heart University Press, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, Connecticut 06825-1000. This book is based on La vie, passionnément Entretiens avec Raymond Flammant French edition published in 2004 by Editions Saint Paul, Luxembourg I dedicate these pages to all those who brought light and warmth to my life. I thank my dear wife Renée for her counsel and advice. I express my particular appreciation to Raymond Flammant, who asked me the right questions. Thanks also to my assistant, Suzanne Cholewka Pinai, for her efficient help. Contents Foreword by Anthony J. Cernera ix Preface xiii Part One / DANCING ON A VOLCANO 1. Pampered Child 3 The Roaring Twenties in Europe 3 Cocooning in the family fold 8 School and self-education 14 The first signs of a devastating blaze 23 The dilemma: die or die in trickles? 27 The “Arlon” plan 30 Part Two / SURVIVING, LIVING, CONSTRUCTING 2. Refugee 35 The rescue operation “Arlon” 35 Erring on the roads of France 38 Montpellier or “The symphony in black” 40 Marseille: a Scottish shower and men with a big heart 43 The unknown heroes of Gibraltar 48 From Casablanca to the shores of liberty 49 viii / CONTENTS 3. -

9783039118458 Intro 002.Pdf

Introduction Crypto-Public Domains within the Third Reich […] heroism […] is to venture wholly to be oneself, as an individual man, this definite individual man, alone before the face of God, alone in this tremendous exertion and this tremendous responsibility […]. — SØren Kierkegaard The Sickness unto Death (1848) This study concentrates on an analysis of public spheres in National Social- ist Germany in order to identify, locate, and investigate circumstances of possible resistance to Adolf Hitler’s regime. The plural use of the word “sphere” is programmatic, since in every society there exist several realms that can function as places of public discourse. We focus on the space of the crypto-public, defined as a politicized private sphere, as a potential realm for anti-state activism. Based on the activities of four organizations operating in Germany between 1933 and 1944—the Jüdischer Kulturbund Berlin ( Jewish Cultural Alliance Berlin), the Kreisauer Kreis (Kreisau Circle), the Scholl- Schmorell-Kreis (Scholl-Schmorell Circle),1 and the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Organisation (Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Organization)—we analyze how this social locus functioned to foster resistance to National Socialism. We examine the artifacts of these groups—leaflets, pamphlets, politico- 1 Traditionally this group has been referred to as Weisse Rose (White Rose); yet, as Sönke Zankel has pertinently argued, that name is misleading, as the Weisse Rose comprised merely the beginning phase of the activities undertaken by the student group sur- rounding Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell (Sönke Zankel, Mit Flugblätter gegen Hitler. Der Widerstandskreis um Hans Scholl und Alexander Schmorell (Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 2008) 13).