Form, Function, and Evolution in Skulls and Teeth of Bats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 41, 2000

BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume 41 : No. 1 Spring 2000 I I BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume 41: Numbers 1–4 2000 Original Issues Compiled by Dr. G. Roy Horst, Publisher and Managing Editor of Bat Research News, 2000. Copyright 2011 Bat Research News. All rights reserved. This material is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced, transmitted, posted on a Web site or a listserve, or disseminated in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the Publisher, Dr. Margaret A. Griffiths. The material is for individual use only. Bat Research News is ISSN # 0005-6227. BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume41 Spring 2000 Numberl Contents Resolution on Rabies Exposure Merlin Tuttle and Thomas Griffiths o o o o eo o o o • o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 o o o o o o o o o o o 0 o o o 1 E - Mail Directory - 2000 Compiled by Roy Horst •••• 0 ...................... 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••• 2 ,t:.'. Recent Literature Compiled by :Margaret Griffiths . : ....••... •"r''• ..., .... >.•••••• , ••••• • ••< ...... 19 ,.!,..j,..,' ""o: ,II ,' f 'lf.,·,,- .,'b'l: ,~··.,., lfl!t • 0'( Titles Presented at the 7th Bat Researc:b Confei'ebee~;Moscow :i'\prill4-16~ '1999,., ..,, ~ .• , ' ' • I"',.., .. ' ""!' ,. Compiled by Roy Horst .. : .......... ~ ... ~· ....... : :· ,"'·~ .• ~:• .... ; •. ,·~ •.•, .. , ........ 22 ·.t.'t, J .,•• ~~ Letters to the Editor 26 I ••• 0 ••••• 0 •••••••••••• 0 ••••••• 0. 0. 0 0 ••••••• 0 •• 0. 0 •••••••• 0 ••••••••• 30 News . " Future Meetings, Conferences and Symposium ..................... ~ ..,•'.: .. ,. ·..; .... 31 Front Cover The illustration of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum on the front cover of this issue is by Philippe Penicaud . from his very handsome series of drawings representing the bats of France. -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)

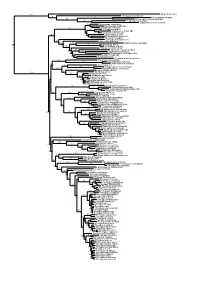

Chapter 6 Phylogenetic Relationships of Harpyionycterine Megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) NORBERTO P. GIANNINI1,2, FRANCISCA CUNHA ALMEIDA1,3, AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT After almost 70 years of stability following publication of Andersen’s (1912) monograph on the group, the systematics of megachiropteran bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) was thrown into flux with the advent of molecular phylogenetics in the 1980s—a state where it has remained ever since. One particularly problematic group has been the Austromalayan Harpyionycterinae, currently thought to include Dobsonia and Harpyionycteris, and probably also Aproteles.Inthis contribution we revisit the systematics of harpyionycterines. We examine historical hypotheses of relationships including the suggestion by O. Thomas (1896) that the rousettine Boneia bidens may be related to Harpyionycteris, and report the results of a series of phylogenetic analyses based on new as well as previously published sequence data from the genes RAG1, RAG2, vWF, c-mos, cytb, 12S, tVal, 16S,andND2. Despite a striking lack of morphological synapomorphies, results of our combined analyses indicate that Boneia groups with Aproteles, Dobsonia, and Harpyionycteris in a well-supported, expanded Harpyionycterinae. While monophyly of this group is well supported, topological changes within this clade across analyses of different data partitions indicate conflicting phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial partition. The position of the harpyionycterine clade within the megachiropteran tree remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, biogeographic patterns (vicariance-dispersal events) within Harpyionycterinae appear clear and can be directly linked to major biogeographic boundaries of the Austromalayan region. The new phylogeny of Harpionycterinae also provides a new framework for interpreting aspects of dental evolution in pteropodids (e.g., reduction in the incisor dentition) and allows prediction of roosting habits for Harpyionycteris, whose habits are unknown. -

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

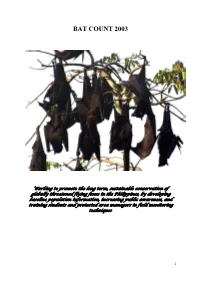

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

The Philippine Flying Foxes, Acerodon Jubatus and Pteropus Vampyrus Lanensis

Journal of Mammalogy, 86(4):719- 728, 2005 DIETARY HABITS OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST BATS: THE PHILIPPINE FLYING FOXES, ACERODON JUBATUS AND PTEROPUS VAMPYRUS LANENSIS Sam C. Stier* and Tammy L. M ildenstein College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59802, USA The endemic and endangered golden- crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) coroosts with the much more common and widespread giant Philippine fmit bat (Pteropus vampyrus ianensis) in lowland dipterocarp forests throughout the Philippine Islands. The number of these mixed roost- colonies and the populations of flying foxes in them have declined dramatically in the last century. We used fecal analysis, interviews of bat hunters, and personal observations to describe the dietary habits of both bat species at one of the largest mixed roosts remaining, near Subic Bay, west- central Luzon. Dietary items were deemed “important” if used consistently on a seasonal basis or throughout the year, ubiquitously throughout the population, and if they were of clear nutritional value. Of the 771 droppings examined over a 2.5 -year period (1998-2000), seeds from Ficus were predominant in the droppings of both species and met these criteria, particularly hemiepiphytic species (41% of droppings of A. jubatus) and Ficus variegata (34% of droppings of P. v. ianensis and 22% of droppings of A. jubatus). Information from bat hunter interviews expanded our knowledge of the dietary habits of both bat species, and corroborated the fecal analyses and personal observations. Results from this study suggest that A. jubatus is a forest obligate, foraging on fruits and leaves from plant species restricted to lowland, mature natural forests, particularly using a small subset of hemiepiphytic and other Ficus species throughout the year. -

Species-Edition-Melanesian-Geo.Pdf

Nature Melanesian www.melanesiangeo.com Geo Tranquility 6 14 18 24 34 66 72 74 82 6 Herping the final frontier 42 Seahabitats and dugongs in the Lau Lagoon 10 Community-based response to protecting biodiversity in East 46 Herping the sunset islands Kwaio, Solomon Islands 50 Freshwater secrets Ocean 14 Leatherback turtle community monitoring 54 Freshwater hidden treasures 18 Monkey-faced bats and flying foxes 58 Choiseul Island: A biogeographic in the Western Solomon Islands stepping-stone for reptiles and amphibians of the Solomon Islands 22 The diversity and resilience of flying foxes to logging 64 Conservation Development 24 Feasibility studies for conserving 66 Chasing clouds Santa Cruz Ground-dove 72 Tetepare’s turtle rodeo and their 26 Network Building: Building a conservation effort network to meet local and national development aspirations in 74 Secrets of Tetepare Culture Western Province 76 Understanding plant & kastom 28 Local rangers undergo legal knowledge on Tetepare training 78 Grassroots approach to Marine 30 Propagation techniques for Tubi Management 34 Phantoms of the forest 82 Conservation in Solomon Islands: acts without actions 38 Choiseul Island: Protecting Mt Cover page The newly discovered Vangunu Maetambe to Kolombangara River Island endemic rat, Uromys vika. Image watershed credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum. wildernesssolomons.com WWW.MELANESIANGEO.COM | 3 Melanesian EDITORS NOTE Geo PRODUCTION TEAM Government Of Founder/Editor: Patrick Pikacha of the priority species listed in the Critical Ecosystem [email protected] Solomon Islands Hails Partnership Fund’s investment strategy for the East Assistant editor: Tamara Osborne Melanesian Islands. [email protected] Barana Community The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Contributing editor: David Boseto [email protected] is designed to safeguard Earth’s most biologically rich Prepress layout: Patrick Pikacha Nature Park Initiative and threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots. -

A Review of the Pteropus Rufus (É. Geoffroy, 1803) Colonies Within The

ARTICLE IN PRESS - EARLY VIEW MADAGASCAR CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT VOLUME 11 | ISSUE 1 — JUNE 2016 page 1 ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mcd.v11i1.7 A review of the Pteropus rufus (É. Geoffroy, 1803) colonies within the Tolagnaro region of southeast Madagascar – an assessment of neoteric threats and conservation condition Sam Hyde RobertsI, Mark D. JacobsI, Ryan M. ClarkI, Correspondence: Charlotte M. DalyII, Longosoa H. TsimijalyIII, Retsiraiky J. Sam Hyde Roberts RossizelaIII, Samuel T. PrettymanI SEED Madagascar, Studio 7, 1A Beethoven Street, London W10 4LG, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT soit parce qu’elles se sont déplacées suite à des dérangements. We surveyed 10 Pteropus rufus roost sites within the sou- Les effectifs d’une seule colonie semblent avoir diminué de theastern Anosy Region of Madagascar to provide an update on manière significative tandis que ceux de trois autres colonies the areas’ known flying fox population and its conservation status. semblent avoir été maintenus à leur niveau. Notre étude a montré We report on two new colonies from Manambaro and Mandena que l'abondance globale de P. rufus dans la région n’a augmenté and provide an account of the colonies first reported and last as- que d’un pourcent depuis 2006 et que cette augmentation était le sessed in 2006. Currently only a solitary roost site receives any résultat de la protection garantie au dortoir dans la réserve privée formal protection (Berenty) whereas further two colonies rely so- de Berenty. À la lumière d'un décret qui a imposé une période de lely on taboo ‘fady’ for their security. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Investigating the Role of Bats in Emerging Zoonoses

12 ISSN 1810-1119 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Cover photographs: Left: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Center: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Right: © Samuel Castro. Bureau of Animal Industry Philippines 12 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Edited by Scott H. Newman, Hume Field, Jon Epstein and Carol de Jong FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2011 Recommended Citation Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. 2011. Investigating the role of bats in emerging zoonoses: Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interests. Edited by S.H. Newman, H.E. Field, C.E. de Jong and J.H. Epstein. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 12. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. -

Flying Foxes): Preliminary Chemical Comparisons Among Species Jamie Wagner SIT Study Abroad

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by World Learning SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2008 Glandular Secretions of Male Pteropus (Flying Foxes): Preliminary Chemical Comparisons Among Species Jamie Wagner SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Wagner, Jamie, "Glandular Secretions of Male Pteropus (Flying Foxes): Preliminary Chemical Comparisons Among Species" (2008). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 559. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/559 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Glandular secretions of male Pteropus (flying foxes): Preliminary chemical comparisons among species By Jamie Wagner Academic Director: Tony Cummings Project Advisor: Dr. Hugh Spencer Oberlin College Biology and Neuroscience Cape Tribulation, Australia Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Australia: Natural and Cultural Ecology, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2008 1 1. Abstract Chemosignaling – passing information by means of chemical compounds that can be detected by members of the same species – is a very important form of communication for most mammals. Flying fox males have odiferous marking secretions on their neck-ruffs that include a combination of secretion from the neck gland and from the urogenital tract; males use this substance to establish territory, especially during the mating season. -

Island Bats: Evolution, Ecology, and Conservation

CHA P T E R 1 3 The Ecology and Conservation of Malagasy Bats Paul A. Racey, Steven M. Goodman, and Richard K. B. Jenkins Introduction Despite the important contribution that bats make to tropical biodiversity and ecosystem function, as well as the threatened status of many species, conserva tion initiatives for Madagascar’s endemic mammals have rarely included bats. Until recently, most mammalogical research in Madagascar concerned lemurs, rodents, and tenrecs. This focus resulted in a dearth of information on bat bi ology. However, since the mid1990s considerable advancement has been made following the establishment of capacitybuilding programs for Malagasy bat biologists, and bats are now included in biodiversity surveys and a growing number of field studies are in progress. In this chapter we summarize the advances made in recent years in un derstanding the diversity of Malagasy bats and briefly describe their biogeo graphic affinities and levels of endemism. We draw attention to the importance of understanding the ecology of these animals and why this is a prerequisite to their conservation. In discussing monitoring and hunting, we highlight some of the reasons that make bat conservation notably different from other vertebrate conservation challenges on the island. The Diversity of Malagasy Bats The recent surge of interest in Malagasy bats has resulted in the discovery and description of nine new taxa on the island. The rate of new discoveries quickly makes statements on endemism and species richness out of date. For example, of the 37 bat taxa listed for Madagascar in table 13.1, only 29 were treated in the 2005 Global Mammal Assessment in Antananarivo.