Bat Count 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predicted the Impacts of Climate Change and Extreme-Weather Events on the Future

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Predicted the impacts of climate change and extreme-weather events on the future distribution of fruit bats in Australia Vishesh L. Diengdoh1, e: [email protected], ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-0797-9261 Stefania Ondei1 - e: [email protected] Mark Hunt1, 3 - e: [email protected] Barry W. Brook1, 2 - e: [email protected] 1School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart TAS 7005 Australia 2ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Australia 3National Centre for Future Forest Industries, Australia Corresponding Author: Vishesh L. Diengdoh Acknowledgements We thank John Clarke and Vanessa Round from Climate Change in Australia (https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/)/ Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) for providing the data on extreme weather events. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council [grant number FL160100101]. Conflict of Interest None. Author Contributions bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. -

Cynopterus Minutus, Minute Fruit Bat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2019: T136423A21985433 Scope: Global Language: English Cynopterus minutus, Minute Fruit Bat Assessment by: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. 2019. Cynopterus minutus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T136423A21985433. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019- 3.RLTS.T136423A21985433.en Copyright: © 2019 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Chiroptera Pteropodidae Taxon Name: Cynopterus minutus Miller, 1906 Common Name(s): • English: Minute Fruit Bat Taxonomic Notes: This may be a species complex. -

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape As A

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape as a Chiropteran Diversity Hotspot in Sumatra Author(s): Joe Chun-Chia Huang, Elly Lestari Jazdzyk, Meyner Nusalawo, Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Sigit Wiantoro, and Tigga Kingston Source: Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2):413-449. Published By: Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/150811014X687369 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3161/150811014X687369 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2): 413–449, 2014 PL ISSN 1508-1109 © Museum and Institute of Zoology PAS doi: 10.3161/150811014X687369 A recent -

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)

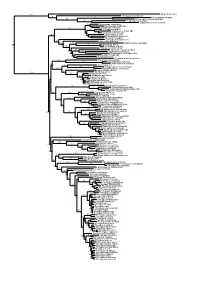

Chapter 6 Phylogenetic Relationships of Harpyionycterine Megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) NORBERTO P. GIANNINI1,2, FRANCISCA CUNHA ALMEIDA1,3, AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT After almost 70 years of stability following publication of Andersen’s (1912) monograph on the group, the systematics of megachiropteran bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) was thrown into flux with the advent of molecular phylogenetics in the 1980s—a state where it has remained ever since. One particularly problematic group has been the Austromalayan Harpyionycterinae, currently thought to include Dobsonia and Harpyionycteris, and probably also Aproteles.Inthis contribution we revisit the systematics of harpyionycterines. We examine historical hypotheses of relationships including the suggestion by O. Thomas (1896) that the rousettine Boneia bidens may be related to Harpyionycteris, and report the results of a series of phylogenetic analyses based on new as well as previously published sequence data from the genes RAG1, RAG2, vWF, c-mos, cytb, 12S, tVal, 16S,andND2. Despite a striking lack of morphological synapomorphies, results of our combined analyses indicate that Boneia groups with Aproteles, Dobsonia, and Harpyionycteris in a well-supported, expanded Harpyionycterinae. While monophyly of this group is well supported, topological changes within this clade across analyses of different data partitions indicate conflicting phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial partition. The position of the harpyionycterine clade within the megachiropteran tree remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, biogeographic patterns (vicariance-dispersal events) within Harpyionycterinae appear clear and can be directly linked to major biogeographic boundaries of the Austromalayan region. The new phylogeny of Harpionycterinae also provides a new framework for interpreting aspects of dental evolution in pteropodids (e.g., reduction in the incisor dentition) and allows prediction of roosting habits for Harpyionycteris, whose habits are unknown. -

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites (Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Upper Marikina-Kaliwa Forest Reserve, Bago River Watershed and Forest Reserve, Naujan Lake National Park and Subwatersheds, Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park and Mt. Apo Natural Park) Philippines Biodiversity & Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy & Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) 23 March 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience Program is funded by the USAID, Contract No. AID-492-C-13-00002 and implemented by Chemonics International in association with: Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program Implemented with: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Other National Government Agencies Local Government Units and Agencies Supported by: United States Agency for International Development Contract No.: AID-492-C-13-00002 Managed by: Chemonics International Inc. in partnership with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) 23 March -

Phivolcs 2003

Cover Design by: Arnold A. Villar Printed & Produced by: PHIVOLCS Publication Copyright: DOST – PHIVOLCS 2003 The ash ejection on 05 April induced related damage in the of the Philippines” under a manned seismic stations. To rose to 1.5 km and deposited province. The earthquake was grant-aid of the Japan Interna- ensure continuity of providing traces of ash in the downwind associated with an 18-km long tional Cooperation Agency basic S & T services should HH iigghhlliigghhttss areas near the crater. On 7 ground rupture onland, which (JICA). The said JICA project the PHIVOLCS main office October, a faint crater glow, transected several barangays is now in its Phase II of im- operation be disrupted in the which can be seen only with of Dimasalang, Palanas and plementation. For volcano future, a mirror station has Two volcanoes, Kanlaon continued for months that a the use of a telescope or night Cataingan. The team verified monitoring, it involves installa- been established in the Ta- and Mayon showed signs of total of forty-six (46) minor vision camera, was observed. the reported ground rupture, tion of radio telemetered gaytay seismic station. This unrest in 2003 prompting ash ejections occurred from 7 On 09 October, sulfur dioxide conducted intensity survey, seismic monitoring system in will house all equipment and PHIVOLCS to raise their Alert March to 23 July 2003. These emission rates rose to 2,386 disseminated correct informa- 8 active volcanoes. In addi- software required to record Level status. Both volcanoes explosions were characterized tonnes per day (t/d) from the tion regarding the event and tion to the regularly monitored and process earthquake data produced ash explosions al- by steam emission with minor previous measurement on 01 installed additional seismo- 6 active volcanoes (Pinatubo, during such emergency. -

Priority-Setting for Philippine Bats Using Practical Approach to Guide Effective Species Conservation and Policy-Making in the Anthropocene

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 30 (1): 74–83, 2019 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it doi:10.4404/hystrix–00172-2019 Research Article Priority-setting for Philippine bats using practical approach to guide effective species conservation and policy-making in the Anthropocene Krizler Cejuela Tanalgo1,2,3,4,∗, Alice Catherine Hughes1,3 1Landscape Ecology Group, Centre for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla, Yunnan Province 666303, People’s Republic of China 2International College, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, People’s Republic of China 3Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla, Yunnan Province 666303, People’s Republic of China 4Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Southern Mindanao, Kabacan 9407, North Cotabato, the Republic of the Philippines Keywords: Abstract asian tropics endemism National level approaches to the development and implementation of effective conservation policy forest loss and practice are often challenged by limited capacity and resources. Developing relevant and hunting achievable priorities at the national level is a crucial step for effective conservation. The Philip- islands pine archipelago includes over 7000 islands and is one of only two countries considered both a oil palm global biodiversity hotspot and a megadiversity country. Yet, few studies have conducted over- arching synthesis for threats and conservation priorities of any species group. As bats make up a Article history: significant proportion of mammalian diversity in the Philippines and fulfil vital roles to maintain Received: 01/19/2019 ecosystem health and services we focus on assessing the threats and priorities to their conserva- Accepted: 24/06/2019 tion across the Philippines. -

A Cryptic Species of the Tylonycteris Pachypus Complex (Chiroptera

Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2014, Vol. 10 200 Ivyspring International Publisher International Journal of Biological Sciences 2014; 10(2):200-211. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7301 Research Paper A Cryptic Species of the Tylonycteris pachypus Complex (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) and Its Population Genetic Structure in Southern China and nearby Regions Chujing HUANG1*, Wenhua YU1*, Zhongxian XU1, Yuanxiong QIU1, Miao CHEN1, Bing QIU1, Masaharu MOTOKAWA2, Masashi HARADA3, Yuchun LI4 and Yi WU1 1. College of Life Sciences, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou 510006, China. 2. The Kyoto University Museum, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan. 3. Laboratory Animal Center, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka City University, Osaka 545-8585, Japan. 4. Marine College, Shandong University (Weihai), Weihai 264209, China. * These authors contribute to this work equally. Corresponding authors: E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]. © Ivyspring International Publisher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Reproduction is permitted for personal, noncommercial use, provided that the article is in whole, unmodified, and properly cited. Received: 2013.07.30; Accepted: 2014.01.09; Published: 2014.02.05 Abstract Three distinct bamboo bat species (Tylonycteris) are known to inhabit tropical and subtropical areas of Asia, i.e., T. pachypus, T. robustula, and T. pygmaeus. This study performed karyotypic examina- tions of 4 specimens from southern Chinese T. p. fulvidus populations and one specimen from Thai T. p. fulvidus population, which detected distinct karyotypes (2n=30) compared with previous karyotypic descriptions of T. p. pachypus (2n=46) and T. robustula (2n=32) from Malaysia. -

The Philippine Flying Foxes, Acerodon Jubatus and Pteropus Vampyrus Lanensis

Journal of Mammalogy, 86(4):719- 728, 2005 DIETARY HABITS OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST BATS: THE PHILIPPINE FLYING FOXES, ACERODON JUBATUS AND PTEROPUS VAMPYRUS LANENSIS Sam C. Stier* and Tammy L. M ildenstein College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59802, USA The endemic and endangered golden- crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) coroosts with the much more common and widespread giant Philippine fmit bat (Pteropus vampyrus ianensis) in lowland dipterocarp forests throughout the Philippine Islands. The number of these mixed roost- colonies and the populations of flying foxes in them have declined dramatically in the last century. We used fecal analysis, interviews of bat hunters, and personal observations to describe the dietary habits of both bat species at one of the largest mixed roosts remaining, near Subic Bay, west- central Luzon. Dietary items were deemed “important” if used consistently on a seasonal basis or throughout the year, ubiquitously throughout the population, and if they were of clear nutritional value. Of the 771 droppings examined over a 2.5 -year period (1998-2000), seeds from Ficus were predominant in the droppings of both species and met these criteria, particularly hemiepiphytic species (41% of droppings of A. jubatus) and Ficus variegata (34% of droppings of P. v. ianensis and 22% of droppings of A. jubatus). Information from bat hunter interviews expanded our knowledge of the dietary habits of both bat species, and corroborated the fecal analyses and personal observations. Results from this study suggest that A. jubatus is a forest obligate, foraging on fruits and leaves from plant species restricted to lowland, mature natural forests, particularly using a small subset of hemiepiphytic and other Ficus species throughout the year. -

Conventional Wisdom on Roosting Behaviour of Australian

Conventional wisdom on roosting behaviour of Australian flying foxes - a critical review, and evaluation using new data Tamika Lunn1, Peggy Eby2, Remy Brooks1, Hamish McCallum1, Raina Plowright3, Maureen Kessler4, and Alison Peel1 1Griffith University 2University of New South Wales 3Montana State University 4Montana State University System April 12, 2021 Abstract 1. Fruit bats (Family: Pteropodidae) are animals of great ecological and economic importance, yet their populations are threatened by ongoing habitat loss and human persecution. A lack of ecological knowledge for the vast majority of Pteropodid bat species presents additional challenges for their conservation and management. 2. In Australia, populations of flying-fox species (Genus: Pteropus) are declining and management approaches are highly contentious. Australian flying-fox roosts are exposed to management regimes involving habitat modification, either through human-wildlife conflict management policies, or vegetation restoration programs. Details on the fine-scale roosting ecology of flying-foxes are not sufficiently known to provide evidence-based guidance for these regimes and the impact on flying-foxes of these habitat modifications is poorly understood. 3. We seek to identify and test commonly held understandings about the roosting ecology of Australian flying-foxes to inform practical recommendations and guide and refine management practices at flying-fox roosts. 4. We identify 31 statements relevant to understanding of flying-fox roosting structure, and synthesise these in the context of existing literature. We then contribute contemporary data on the fine-scale roosting structure of flying-fox species in south-eastern Queensland and north- eastern New South Wales, presenting a 13-month dataset from 2,522 spatially referenced roost trees across eight sites. -

NHBSS 042 1O Robinson Obs

Notes NAT. NAT. HIST. B 肌 L. SIAM Soc. 42: 117-120 , 1994 Observation Observation on the Wildlife Trade at the Daily Market in Chiang Kh an , Northeast Thailand In In a recent study into the wildlife trade between Lao PDR. and Thailand S即 KOSAMAT 組 A et al. (1 992) found 伽 tit was a major 伽 eat to wildlife resources in Lao. Th ey surveyed 15 locations along 白e 百凶 Lao border ,including Chiang Kh an. Only a single single visit was made to the market in Chiang Kh佃, on 8 April 1991 , and no wildlife products products were found. τbe border town of Chi 佃 g Kh an , Loei Pr ovince in northeast 百lailand is situated on the the banks of the Mekong river which sep 釘 ates Lao PD R. and 官 lailand. In Chiang Kh an there there is a small market held twice each day. Th e market ,situated in the centre of town , sells sells a wide r佃 ge of products from f記sh fruit ,vegetables , meat and dried fish to clothes and and household items. A moming market begins around 0300 h and continues until about 0800 h. The evening market st 紅白紙 1500 h and continues until about 1830 h. During During the period November 1992 to November 1993 visits were made to Chiang Kh佃 eve 凶ng market , to record the wildlife offered for sale. Only the presence of mam- mals ,reptiles and birds was recorded. Although frogs ,insects ,fish , crabs and 加 t eggs , as as well as meat 仕om domestic animals , were sold ,no record of this was made.