The Philippine Flying Foxes, Acerodon Jubatus and Pteropus Vampyrus Lanensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predicted the Impacts of Climate Change and Extreme-Weather Events on the Future

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Predicted the impacts of climate change and extreme-weather events on the future distribution of fruit bats in Australia Vishesh L. Diengdoh1, e: [email protected], ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-0797-9261 Stefania Ondei1 - e: [email protected] Mark Hunt1, 3 - e: [email protected] Barry W. Brook1, 2 - e: [email protected] 1School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart TAS 7005 Australia 2ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Australia 3National Centre for Future Forest Industries, Australia Corresponding Author: Vishesh L. Diengdoh Acknowledgements We thank John Clarke and Vanessa Round from Climate Change in Australia (https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/)/ Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) for providing the data on extreme weather events. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council [grant number FL160100101]. Conflict of Interest None. Author Contributions bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. -

Living with Wildlife - Flying Foxes Fact Sheet No

LIVING WITH WILDLIFE - FLYING FOXES FACT SHEET NO. 0063 Living with wildlife - Flying Foxes What are flying foxes? flying foxes use to mark their territory and to attract females during the mating season. Flying foxes, also known as fruit bats, are winged mammals belonging to the sub-order group of megabats. Unlike the smaller insectivorous microbats, the Do flying foxes carry diseases? animal navigates using their eye sight and smell, as opposed to echolocation, Like most wildlife and pets, flying foxes may carry diseases that can affect and feed on nectar, pollen and fruit. Flying foxes forage from over 100 humans. Australian Bat Lyssavirus can be transmitted directly from flying species of native plants and may supplement this diet with introduced plants foxes to humans. The risk of contracting Lyssavirus is extremely low, with found in gardens, orchards and urban areas. transmission only possible through direct contact of saliva from an infected Of the four species of flying foxes native to mainland Australia, three reside animal with a skin penetrating bite or scratch. in the Gladstone Region. These species include the grey-headed flying fox Flying foxes are natural hosts of the Hendra virus, however, there is no (Pteropus poliocephalus), black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) and little red evidence that the virus can be transmitted directly to humans. It is believed flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus). that the virus is transmitted from flying foxes to horses through exposure to All of these species are protected under the Nature Conservation Act urine or birthing fluids. Vaccination is the most effective way of reducing the 1992 and the grey-headed flying fox is also listed as ‘vulnerable’ under the risk of the virus infecting horses. -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia

CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation i ii CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation By Ibnu Maryanto Maharadatunkamsi Anang Setiawan Achmadi Sigit Wiantoro Eko Sulistyadi Masaaki Yoneda Agustinus Suyanto Jito Sugardjito RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) iii © 2019 RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) Cataloging in Publication Data. CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA: Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation/ Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Anang Setiawan Achmadi, Sigit Wiantoro, Eko Sulistyadi, Masaaki Yoneda, Agustinus Suyanto, & Jito Sugardjito. ix+ 66 pp; 21 x 29,7 cm ISBN: 978-979-579-108-9 1. Checklist of mammals 2. Indonesia Cover Desain : Eko Harsono Photo : I. Maryanto Third Edition : December 2019 Published by: RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI). Jl Raya Jakarta-Bogor, Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16911 Telp: 021-87907604/87907636; Fax: 021-87907612 Email: [email protected] . iv PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION This book is a third edition of checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia. The new edition provides remarkable information in several ways compare to the first and second editions, the remarks column contain the abbreviation of the specific island distributions, synonym and specific location. Thus, in this edition we are also corrected the distribution of some species including some new additional species in accordance with the discovery of new species in Indonesia. -

WIAD CONSERVATION a Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity

WIAD CONSERVATION A Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity WIAD CONSERVATION A Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 2 Ohu Map ...................................................................................................................................... 3 History of WIAD Conservation ...................................................................................................... 4 WIAD Legends .............................................................................................................................. 7 The Story of Julug and Tabalib ............................................................................................................... 7 Mou the Snake of A’at ........................................................................................................................... 8 The Place of Thunder ........................................................................................................................... 10 The Stone Mirror ................................................................................................................................. 11 The Weather Bird ................................................................................................................................ 12 The Story of Jelamanu Waterfall ......................................................................................................... -

Phenology of Ficus Variegata in a Seasonal Wet Tropical Forest At

Joumalof Biogeography (I1996) 23, 467-475 Phenologyof Ficusvariegata in a seasonalwet tropicalforest at Cape Tribulation,Australia HUGH SPENCER', GEORGE WEIBLENI 2* AND BRIGITTA FLICK' 'Cape TribulationResearch Station, Private Mail Bag5, Cape Tribulationvia Mossman,Queensland 4873, Australiaand 2 The Harvard UniversityHerbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue,Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA Abstract. We studiedthe phenologyof 198 maturetrees dioecious species, female and male trees initiatedtheir of the dioecious figFicus variegataBlume (Moraceae) in a maximalfig crops at differenttimes and floweringwas to seasonally wet tropical rain forestat Cape Tribulation, some extentsynchronized within sexes. Fig productionin Australia, from March 1988 to February 1993. Leaf the female (seed-producing)trees was typicallyconfined productionwas highlyseasonal and correlatedwith rainfall. to the wet season. Male (wasp-producing)trees were less Treeswere annually deciduous, with a pronouncedleaf drop synchronizedthan femaletrees but reacheda peak level of and a pulse of new growthduring the August-September figproduction in the monthsprior to the onset of female drought. At the population level, figs were produced figproduction. Male treeswere also morelikely to produce continuallythroughout the study but there were pronounced figscontinually. Asynchrony among male figcrops during annual cyclesin figabundance. Figs were least abundant the dry season could maintainthe pollinatorpopulation duringthe early dry period (June-September)and most under adverseconditions -

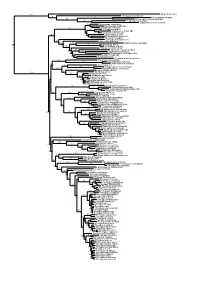

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Rainforest Disturbance Affects Population Density of the Northern Cassowary Casuarius Unappendiculatus in Papua, Indonesia

Rainforest disturbance affects population density of the northern cassowary Casuarius unappendiculatus in Papua, Indonesia M ARGARETHA P ANGAU-ADAM,MICHAEL M ÜHLENBERG and M ATTHIAS W ALTERT Abstract Nominally protected areas in Papua are under and human population growth are leading to high rates threat from encroachment, logging and hunting. The of deforestation and forest conversion. Besides disturbance northern cassowary Casuarius unappendiculatus is the from logging, large-scale oil palm plantations are the pri- largest frugivore of the lowland rainforest of New Guinea mary cause of the loss of lowland forest in Papua (Frazier, and is endemic to this region, and therefore it is an 2007). A number of conservation areas and protection important conservation target and a potential flagship forests have been established in this region (de Fretes, 2007) species. We investigated effects of habitat degradation on the but agricultural encroachment, illegal logging and hunting species by means of distance sampling surveys of 58 line by immigrants and local communities are common. As in transects across five distinct habitats, from primary forest to other parts of the tropics, local extinction of forest avifauna forest gardens. Estimated cassowary densities ranged from following forest fragmentation and extensive forest clearing −2 14.1 (95%CI9.2–21.4) birds km in primary forest to 1.4 is to be expected (Kattan et al., 1994; Castelletta et al., 2000; −2 (95%CI0.4–5.6) birds km in forest garden. Density Waltert et al., 2004). Large forest birds such as cassowaries estimates were intermediate in unlogged but hunted natural (Casuarius spp.) are particularly likely to disappear if forest and in . -

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter Number 29 November 2007 ABS Website: http://abs.ausbats.org.au ABS Listserver: http://listserv.csu.edu.au/mailman/listinfo/abs ISSN 1448-5877 The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 29, November 2007 – Instructions for contributors – The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter will accept contributions under one of the following two sections: Research Papers, and all other articles or notes. There are two deadlines each year: 31st March for the April issue, and 31st October for the November issue. The Editor reserves the right to hold over contributions for subsequent issues of the Newsletter, and meeting the deadline is not a guarantee of immediate publication. Opinions expressed in contributions to the Newsletter are the responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australasian Bat Society, its Executive or members. For consistency, the following guidelines should be followed: • Emailed electronic copy of manuscripts or articles, sent as an attachment, is the preferred method of submission. Manuscripts can also be sent on 3½” floppy disk, preferably in IBM format. Please use the Microsoft Word template if you can (available from the editor). Faxed and hard copy manuscripts will be accepted but reluctantly! Please send all submissions to the Newsletter Editor at the email or postal address below. • Electronic copy should be in 11 point Arial font, left and right justified with 16 mm left and right margins. Please use Microsoft Word; any version is acceptable. • Manuscripts should be submitted in clear, concise English and free from typographical and spelling errors. Please leave two spaces after each sentence. -

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites (Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Upper Marikina-Kaliwa Forest Reserve, Bago River Watershed and Forest Reserve, Naujan Lake National Park and Subwatersheds, Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park and Mt. Apo Natural Park) Philippines Biodiversity & Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy & Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) 23 March 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience Program is funded by the USAID, Contract No. AID-492-C-13-00002 and implemented by Chemonics International in association with: Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program Implemented with: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Other National Government Agencies Local Government Units and Agencies Supported by: United States Agency for International Development Contract No.: AID-492-C-13-00002 Managed by: Chemonics International Inc. in partnership with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) 23 March -

Isolation and Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Flavonoid from Ficus Variegata Blume

538 Indones. J. Chem., 2019, 19 (2), 538 - 543 NOTE: Isolation and Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Flavonoid from Ficus variegata Blume Rolan Rusli*, Bela Apriliana Ningsih, Agung Rahmadani, Lizma Febrina, Vina Maulidya, and Jaka Fadraersada Pharmacotropics Laboratory, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Mulawarman, Gunung Kelua, Samarinda 75119, East Kalimantan, Indonesia * Corresponding author: Abstract: Ficus variegata Blume is a specific plant of East Kalimantan. Flavonoid compound of F. variegata Blume was isolated by vacuum liquid and column tel: +62-85222221907 chromatography, with previously extracted by maceration method using n-hexane and email: [email protected] methanol, and fractionation using ethyl acetate solvent. The eluent used in isolation were Received: April 12, 2017 n-hexane:ethyl acetate (8:2). Based on the results of elucidation structure using Accepted: January 29, 2018 spectroscopy methods (GC-MS, NMR, and FTIR), 5-hydroxy-2-(4-methoxy-phenyl)-8,8- DOI: 10.22146/ijc.23947 dimethyl-8H-pyrano[2,3-f] chromen-4-one was obtained. This compound has antibacterial and antioxidant activity. Keywords: Ficus variegata Blume; flavonoid; antibacterial activities; antioxidant activity ■ INTRODUCTION much every time it produces fruit. Due that, this plant is a potential plant to be used as medicinal plant. Ficus is a genus that has unique characteristics, and F. variegata Blume is usually used as traditional it grows mainly in tropical rainforest [1-3]. Secondary medicine for treatment of various illnesses, i.e., metabolite of the genus Ficus is rich in polyphenolic dysentery and ulceration. Our research group has been compounds, and flavonoids, therefore, the genus Ficus is reported the bioactivity of a secondary metabolite from usually used as traditional medicine for treatment of leaves, stem bark, and fruit of F. -

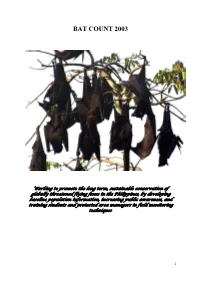

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area.