A Review of the Pteropus Rufus (É. Geoffroy, 1803) Colonies Within The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Book of Abstracts IB2019

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Université de la Réunion Campus du Moufia 2 Island Biology Third International Conference on Island Ecology, Evolution and Conservation 8-13 July 2019 University of La R´eunion Saint Denis, France Book of Abstracts Editors: Olivier Flores Claudine Ah-Peng Nicholas Wilding Description of contents This document contains the collection of abstracts describing the research works presented at the third international conference on island ecology, evolution and conservation, Island Biology 2019, held in Saint Denis (La R´eunion,8-13 July 2019). In the following order, the different parts of this document concern Plenary sessions, Symposia, Regular sessions, and Poster presentations organized in thematic sections. The last part of the document consists of an author index with the names of all authors and links to the corresponding abstracts. Each abstract is referenced by a unique number 6-digits number indicated at the bottom of each page on the right. This reference number points to the online version of the abstract on the conference website using URL https://sciencesconf.org:ib2019/xxxxxx, where xxxxxx is the reference of the abstract. 4 Table of contents Plenary Sessions 19 Introduction to natural history of the Mascarene islands, Dominique Strasberg . 20 The history, current status, and future of the protected areas of Madagascar, Steven M. Goodman............................................ 21 The island biogeography of alien species, Tim Blackburn.................. 22 What can we learn about invasion ecology from ant invasions of islands ?, Lori Lach . 23 Orchids, moths, and birds on Madagascar, Mauritius, and Reunion: island systems with well-constrained timeframes for species interactions and trait change, Susanne Renner . -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Ctz78-02 (02) Lee Et Al.Indd 51 14 08 2009 13:12 52 Lee Et Al

Contributions to Zoology, 78 (2) 51-64 (2009) Variation in the nocturnal foraging distribution of and resource use by endangered Ryukyu flying foxes(Pteropus dasymallus) on Iriomotejima Island, Japan Ya-Fu Lee1, 4, Tokushiro Takaso2, 5, Tzen-Yuh Chiang1, 6, Yen-Min Kuo1, 7, Nozomi Nakanishi2, 8, Hsy-Yu Tzeng3, 9, Keiko Yasuda2 1 Department of Life Sciences and Institute of Biodiversity, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 701, Taiwan 2 The Iriomote Project, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, 671 Iriomote, Takatomi-cho, Okinawa 907- 1542, Japan 3 Hengchun Research Center, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Pingtung 946, Taiwan 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 E-mail: [email protected] 6 E-mail: [email protected] 7 E-mail: [email protected] 8 E-mail: [email protected] 9 E-mail: [email protected] Key words: abundance, bats, Chiroptera, diet, figs, frugivores, habitat Abstract Contents The nocturnal distribution and resource use by Ryukyu flying foxes Introduction ........................................................................................ 51 was studied along 28 transects, covering five types of habitats, on Material and methods ........................................................................ 53 Iriomote Island, Japan, from early June to late September, 2005. Study sites ..................................................................................... 53 Bats were mostly encountered solitarily (66.8%) or in pairs (16.8%), Bat and habitat census ................................................................ -

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-Colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa The adaptation of bats (order Chiroptera) to use and For these reasons, we assessed the seasonality of occupy human dwellings across the planet has created coronavirus (CoV) shedding by the straw-colored intensive bat-human interfaces. Because bats provide fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) by passively collecting 97 important ecosystem services and also host and shed fecal samples on a monthly basis during a entire year zoonotic viruses, these interfaces represent a double in two urban colonies: Accra, Ghana (West Africa) challenge: i) the conservation of bats and their services and Morogoro, Tanzania (East Africa; Fig 1). Sampling and ii) the prevention of viral spillover. collection was conducted under the same trees during Many species of bats have evolved a seasonal life the study period. This species of fruit bat shows a single history that has resulted in the development of specific birth pulse during the year, its colonies show spectacular reproductive and foraging activities during distinctive periodical changes in size, and similarly to other tree- periods of the year. For example, many species mate, roosting megabats, several roosts are located in busy give birth, and nurse during particular and predictable urban centers across sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, times of the year. Moreover, bat migration can produce we concomitantly collected data on the roost sizes predictable variations in colony sizes during a typical and precipitation levels over time, and we established year, from a complete absence of bats to the aggregation the reproductive periods through the year (birth of millions of individuals depending on the season. -

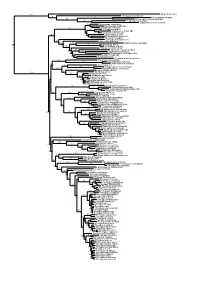

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Ctz78-02 (02) Lee Et Al.Indd 51 14 08 2009 13:12 52 Lee Et Al

Contributions to Zoology, 78 (2) 51-64 (2009) Variation in the nocturnal foraging distribution of and resource use by endangered Ryukyu flying foxes(Pteropus dasymallus) on Iriomotejima Island, Japan Ya-Fu Lee1, 4, Tokushiro Takaso2, 5, Tzen-Yuh Chiang1, 6, Yen-Min Kuo1, 7, Nozomi Nakanishi2, 8, Hsy-Yu Tzeng3, 9, Keiko Yasuda2 1 Department of Life Sciences and Institute of Biodiversity, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 701, Taiwan 2 The Iriomote Project, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, 671 Iriomote, Takatomi-cho, Okinawa 907- 1542, Japan 3 Hengchun Research Center, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Pingtung 946, Taiwan 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 E-mail: [email protected] 6 E-mail: [email protected] 7 E-mail: [email protected] 8 E-mail: [email protected] 9 E-mail: [email protected] Key words: abundance, bats, Chiroptera, diet, figs, frugivores, habitat Abstract Contents The nocturnal distribution and resource use by Ryukyu flying foxes Introduction ........................................................................................ 51 was studied along 28 transects, covering five types of habitats, on Material and methods ........................................................................ 53 Iriomote Island, Japan, from early June to late September, 2005. Study sites ..................................................................................... 53 Bats were mostly encountered solitarily (66.8%) or in pairs (16.8%), Bat and habitat census ................................................................ -

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

The Philippine Flying Foxes, Acerodon Jubatus and Pteropus Vampyrus Lanensis

Journal of Mammalogy, 86(4):719- 728, 2005 DIETARY HABITS OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST BATS: THE PHILIPPINE FLYING FOXES, ACERODON JUBATUS AND PTEROPUS VAMPYRUS LANENSIS Sam C. Stier* and Tammy L. M ildenstein College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59802, USA The endemic and endangered golden- crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) coroosts with the much more common and widespread giant Philippine fmit bat (Pteropus vampyrus ianensis) in lowland dipterocarp forests throughout the Philippine Islands. The number of these mixed roost- colonies and the populations of flying foxes in them have declined dramatically in the last century. We used fecal analysis, interviews of bat hunters, and personal observations to describe the dietary habits of both bat species at one of the largest mixed roosts remaining, near Subic Bay, west- central Luzon. Dietary items were deemed “important” if used consistently on a seasonal basis or throughout the year, ubiquitously throughout the population, and if they were of clear nutritional value. Of the 771 droppings examined over a 2.5 -year period (1998-2000), seeds from Ficus were predominant in the droppings of both species and met these criteria, particularly hemiepiphytic species (41% of droppings of A. jubatus) and Ficus variegata (34% of droppings of P. v. ianensis and 22% of droppings of A. jubatus). Information from bat hunter interviews expanded our knowledge of the dietary habits of both bat species, and corroborated the fecal analyses and personal observations. Results from this study suggest that A. jubatus is a forest obligate, foraging on fruits and leaves from plant species restricted to lowland, mature natural forests, particularly using a small subset of hemiepiphytic and other Ficus species throughout the year. -

Conventional Wisdom on Roosting Behaviour of Australian

Conventional wisdom on roosting behaviour of Australian flying foxes - a critical review, and evaluation using new data Tamika Lunn1, Peggy Eby2, Remy Brooks1, Hamish McCallum1, Raina Plowright3, Maureen Kessler4, and Alison Peel1 1Griffith University 2University of New South Wales 3Montana State University 4Montana State University System April 12, 2021 Abstract 1. Fruit bats (Family: Pteropodidae) are animals of great ecological and economic importance, yet their populations are threatened by ongoing habitat loss and human persecution. A lack of ecological knowledge for the vast majority of Pteropodid bat species presents additional challenges for their conservation and management. 2. In Australia, populations of flying-fox species (Genus: Pteropus) are declining and management approaches are highly contentious. Australian flying-fox roosts are exposed to management regimes involving habitat modification, either through human-wildlife conflict management policies, or vegetation restoration programs. Details on the fine-scale roosting ecology of flying-foxes are not sufficiently known to provide evidence-based guidance for these regimes and the impact on flying-foxes of these habitat modifications is poorly understood. 3. We seek to identify and test commonly held understandings about the roosting ecology of Australian flying-foxes to inform practical recommendations and guide and refine management practices at flying-fox roosts. 4. We identify 31 statements relevant to understanding of flying-fox roosting structure, and synthesise these in the context of existing literature. We then contribute contemporary data on the fine-scale roosting structure of flying-fox species in south-eastern Queensland and north- eastern New South Wales, presenting a 13-month dataset from 2,522 spatially referenced roost trees across eight sites. -

Final Report on the Project

BP Conservation Programme (CLP) 2005 PROJECT NO. 101405 - BRONZE AWARD WINNER ECOLOGY, DISTRIBUTION, STATUS AND PROTECTION OF THREE CONGOLESE FRUIT BATS FINAL REPORT Patrick KIPALU Team Leader Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement OCPE – ong Kinshasa – Democratic Republic of the Congo E-mail: [email protected] APRIL 2009 1 Table of Content Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. p3 I. Project Summary……………………………………………………………….. p4 II. Introduction…………………………………………………………………… p4-p7 III. Materials and Methods ……………………………………………………….. p7-p10 IV. Results per Study Site…………………………………………………………. p10-p15 1. Pointe-Noire ………………………………………………………….. p10-p12 2. Mayumbe Forest /Luki Reserve……………………………………….. p12-p13 3. Zongo Forest…………………………………………………………... p14 4. Mbanza-Ngungu ………………………………………………………. P15 V. General Results ………………………………………………………………p15-p16 VI. Discussions……………………………………………………………………p17-18 VII. Conclusion and Recommendations……………………………………….p 18-p19 VIII. Bibliography………………………………………………………………p20-p21 Acknowledgements 2 The OCPE (Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement) project team would like to start by expressing our gratefulness and saying thank you to the BP Conservation Program, which has funded the execution of this project. The OCPE also thanks the Van Tienhoven Foundation which provided a further financial support. Without these organisations, execution of the project would not have been possible. We would like to thank specially the BPCP “dream team”: Marianne D. Carter, Robyn Dalzen and our regretted Kate Stoke for their time, advices, expertise and care, which helped us to complete this work, Our special gratitude goes to Dr. Wim Bergmans, who was the hero behind the scene from the conception to the execution of the research work. Without his expertise, advices and network it would had been difficult for the project team to produce any result from this project. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Babesial Infection in the Madagascan Flying Fox, Pteropus Rufus É

Ranaivoson et al. Parasites & Vectors (2019) 12:51 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3300-7 RESEARCH Open Access Babesial infection in the Madagascan flying fox, Pteropus rufus É. Geoffroy, 1803 Hafaliana C. Ranaivoson1,2, Jean-Michel Héraud1, Heidi K. Goethert3, Sam R. Telford III3, Lydia Rabetafika2† and Cara E. Brook4,5*† Abstract Background: Babesiae are erythrocytic protozoans, which infect the red blood cells of vertebrate hosts to cause disease. Previous studies have described potentially pathogenic infections of Babesia vesperuginis in insectivorous bats in Europe, the Americas and Asia. To date, no babesial infections have been documented in the bats of Madagascar, or in any frugivorous bat species worldwide. Results: We used standard microscopy and conventional PCR to identify babesiae in blood from the endemic Madagascan flying fox (Pteropus rufus). Out of 203 P. rufus individuals captured between November 2013 and January 2016 and screened for erythrocytic parasites, nine adult males (4.43%) were infected with babesiae. Phylogenetic analysis of sequences obtained from positive samples indicates that they cluster in the Babesia microti clade, which typically infect felids, rodents, primates, and canids, but are distinct from B. vesperuginis previously described in bats. Statistical analysis of ecological trends in the data suggests that infections were most commonly observed in the rainy season and in older-age individuals. No pathological effects of infection on the host were documented; age-prevalence patterns indicated susceptible-infectious (SI) transmission dynamics characteristic of a non-immunizing persistent infection. Conclusions: To our knowledge, this study is the first report of any erythrocytic protozoan infecting Madagascan fruit bats and the first record of a babesial infection in a pteropodid fruit bat globally.