Dog-Faced Fruit Bat) in Bintulu, Sarawak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cynopterus Minutus, Minute Fruit Bat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2019: T136423A21985433 Scope: Global Language: English Cynopterus minutus, Minute Fruit Bat Assessment by: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. 2019. Cynopterus minutus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T136423A21985433. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019- 3.RLTS.T136423A21985433.en Copyright: © 2019 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Chiroptera Pteropodidae Taxon Name: Cynopterus minutus Miller, 1906 Common Name(s): • English: Minute Fruit Bat Taxonomic Notes: This may be a species complex. -

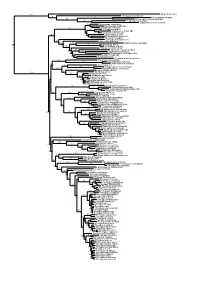

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

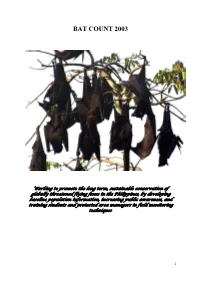

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Bat Coronaviruses and Experimental Infection of Bats, the Philippines Shumpei Watanabe, Joseph S

Bat Coronaviruses and Experimental Infection of Bats, the Philippines Shumpei Watanabe, Joseph S. Masangkay, Noriyo Nagata, Shigeru Morikawa, Tetsuya Mizutani, Shuetsu Fukushi, Phillip Alviola, Tsutomu Omatsu, Naoya Ueda, Koichiro Iha, Satoshi Taniguchi, Hikaru Fujii, Shumpei Tsuda, Maiko Endoh, Kentaro Kato, Yukinobu Tohya, Shigeru Kyuwa, Yasuhiro Yoshikawa, and Hiroomi Akashi Fifty-two bats captured during July 2008 in the Philip- voirs for SARS-CoV. These survey fi ndings suggested that pines were tested by reverse transcription–PCR to detect palm civets and raccoon dogs are an intermediate host of, bat coronavirus (CoV) RNA. The overall prevalence of vi- but not a primary reservoir for, SARS-CoV because of the rus RNA was 55.8%. We found 2 groups of sequences that low prevalence of SARS-like CoVs in these animals (2). belonged to group 1 (genus Alphacoronavirus) and group Moreover, a large variety of novel CoVs in these surveys, 2 (genus Betacoronavirus) CoVs. Phylogenetic analysis including bat SARS–like CoVs, were detected in many bat of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene showed that groups 1 and 2 CoVs were similar to Bat-CoV/China/ species in the People’s Republic of China and Hong Kong A515/2005 (95% nt sequence identity) and Bat-CoV/ Special Administrative Region (3–6). HKU9–1/China/2007 (83% identity), respectively. To propa- Phylogenetic analysis of bat CoVs and other known gate group 2 CoVs obtained from a lesser dog-faced fruit bat CoVs suggested that the progenitor of SARS-CoV and all (Cynopterus brachyotis), we administered intestine samples other CoVs in other animal hosts originated in bats (5,7). -

Investigating the Role of Bats in Emerging Zoonoses

12 ISSN 1810-1119 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Cover photographs: Left: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Center: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Right: © Samuel Castro. Bureau of Animal Industry Philippines 12 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Edited by Scott H. Newman, Hume Field, Jon Epstein and Carol de Jong FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2011 Recommended Citation Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. 2011. Investigating the role of bats in emerging zoonoses: Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interests. Edited by S.H. Newman, H.E. Field, C.E. de Jong and J.H. Epstein. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 12. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. -

Habitat Selection of Endangered and Endemic Large Flying-Foxes in Subic

Biological Conservation 126 (2005) 93–102 www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Habitat selection of endangered and endemic large Xying-foxes in Subic Bay, Philippines Tammy L. Mildenstein a,¤, Sam C. Stier a, C.E. Nuevo-Diego b, L. Scott Mills c a c/o US Peace Corps, Patio Madrigal Compound, 2775 Roxas Blvd., Pasay City, Metro Manila, Philippines b 9872 Isarog St. Umali Subdivision, Los Baños, Laguna 4031, Philippines c Wildlife Biology Program, School of Forestry, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812-0596, USA Received 6 June 2004 Available online 5 July 2005 Abstract Large Xying-foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to high levels of deforestation and hunting and eVectively little local conservation commitment. The forest at Subic Bay, Philippines, supports a rare, large colony of vulnerable Philippine giant fruit bats (Pteropus vampyrus lanensis) and endangered and endemic golden-crowned Xying-foxes (Acerodon jubatus). These large Xying-foxes are optimal for conservation focus, because in addition to being keystone, Xagship, and umbrella species, the bats are important to Subic Bay’s economy and its indigenous cultures. Habitat selection information stream- lines management’s eVorts to protect and conserve these popular but threatened animals. We used radio telemetry to describe the bats’ nighttime use of habitat on two ecological scales: vegetation and microhabitat. The fruit bats used the entire 14,000 ha study area, including all of Subic Bay Watershed Reserve, as well as neighboring forests just outside the protected area boundaries. Their recorded foraging locations ranged between 0.4 and 12 km from the roost. -

Morphometric Analysis of Bats (Chiroptera) in the Campus Area Of

Advances in Biological Sciences Research, volume 14 Proceedings of the 3rd KOBI Congress, International and National Conferences (KOBICINC 2020) Morphometric Analysis of Bats (Chiroptera) in the Campus Area of the University of Bengkulu, Using Principal Component Analysis Santi Nurul Kamilah1,* Mahesha Rama2 Jarulis1 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Bengkulu, Kandang Limun, Bengkulu 38112, Indonesia 2Undergraduate Student, Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Bengkulu, Kandang Limun, Bengkulu 38112, Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Bats are the true flying mammals in the world. Morphological identification based upon morphometric characteristics will needed to determine the type of bat species, particularly the closely related species with the high level of morphological similarity. This study was aimed to determine the distinguishing characteristics between bat species found in the campus area of the University of Bengkulu. Bats were caught using mist net. The data of body morphometric measurement of each bat was analyzed using the software of MINITAB 18. As a result, there were four species, namely Cynopterus branchyotis, Cynopterus sphinx of the suborder Megachiroptera, Macroglossus sobrinus, and Rhinolophus stheno of the suborder Microchiroptera. The main distinguishing morphometric characteristics between species within genus were forearm length and tibia length. Based on the morphometric characteristic of all bat species found in this study, Cynopterus branchyotis and Cynopterus sphinx was found to be the most closely related with a Similarity Index of 77.99%, while the Similarity Index between the species and Rhinolophus stheno was 28.87%. Moreover, the lowest Similarity Index was obtained between the species and Macroglossus sobrinus of only 0.01%. -

Integrated Fossil and Molecular Data Reconstruct Bat Echolocation

Integrated fossil and molecular data reconstruct bat echolocation Mark S. Springer†‡, Emma C. Teeling†§, Ole Madsen¶, Michael J. Stanhope§ʈ, and Wilfried W. de Jong¶** †Department of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521; §Queen’s University of Belfast, Biology and Biochemistry, 97 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 7BL, United Kingdom; ¶Department of Biochemistry, University of Nijmegen, P.O. Box 9101, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands; ʈBioinformatics, SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, 1250 South Collegeville Road, UP1345, Collegeville, PA 19426; and **Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, 1090 GT Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edited by David Pilbeam, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved March 26, 2001 (received for review November 21, 2000) Molecular and morphological data have important roles in illumi- tulates a sister-group relationship between flying lemurs and bats nating evolutionary history. DNA data often yield well resolved (6). Although some authors have questioned bat monophyly phylogenies for living taxa, but are generally unattainable for based on evidence from the penis and nervous system (7, 8), the fossils. A distinct advantage of morphology is that some types of bulk of morphological data supports bat monophyly (9). Among morphological data may be collected for extinct and extant taxa. living Chiroptera, morphological data provide strong support for Fossils provide a unique window on evolutionary history and may the reciprocal monophyly of megachiropterans (Old World fruit preserve combinations -

Roosting Ecology and Morphometric Analysis of Pteropus Medius (Indian Flying Fox) in Lower Dir, District, Pakistan W

Brazilian Journal of Biology https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.221935 ISSN 1519-6984 (Print) Original Article ISSN 1678-4375 (Online) Roosting ecology and morphometric analysis of Pteropus medius (Indian flying fox) in Lower Dir, district, Pakistan W. Khana* , N.N. Nisab , A. R. Khana , B. Rahbarc, S.A. Mehmoodc , S. Ahmedc , M. Kamald , M. Shahe , A. Rasoole , W.A. Pahanwarf , I. Ullahg and S. Khana aDepartment of Zoology, University of Malakand, Lower Dir, Pakistan bPakistan Agricultural Research Council, Southern Zone-Agricultural Research Center, Vertebrate Pest Control Institute, University Campus, Karachi, Pakistan cDepartment of Zoology, Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan dDepartment of Zoology, University of Karachi, Karachi-Pakistan eDepartment of Zoology, University of Swat, Pakistan fDepartment of Zoology, Shah Abdul Latif University Khairpur Miris Sindh, Pakistan gDepartment of Biological Sciences Karakuram, International University Gilgit, Pakistan *e-mail: [email protected] Received: March 28, 2019 – Accepted: May 21, 2019 – Distributed: February 28, 2021 Abstract The present study was conducted to explore morphometric variations of Pteropus medius (the Indian flying fox) and the roosting trees in Lower Dir, Pakistan. The bats were captured from Morus alba, Morus nigra, Brousonetia papyrifera, Pinus raxburghii, Hevea brasiliensis, Platanus orientalis, Populous nigra, Melia azedarach, Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Grevillea robusta through sling shot and mess net methods. A total of 12 bats were studied for the differential -

Suggested Guidelines for Bat Enrichment Bats in the Wild Have A

Suggested Guidelines for Bat Enrichment Bats in the wild have a life that is filled with dynamic experiences, such as those associated with avoiding predators, searching for and acquiring food, defending territories and producing viable offspring (Martin, 1996). The theory of natural selection suggests that only the fittest of a species survive (Darwin, 1859). In captivity, the primary survival needs of bats are fulfilled by their caregivers, leaving the animals with few choices and few consequences. According to the welfare criterion of Maple, McManamon, and Stevens (1995), treatment of captive animals should achieve a level of well-being comparable to, or better than, the life they could be expected to live in the wild (Wuichet and Norton, 1995). Environment has an immediate effect on mammals after birth. The effects of the rearing environment can have far reaching results. Studies have shown that developing mammals are more likely to learn that they can exert “control” over their environment in a physically complex surrounding (Renner, 1998; Joffe et al,. 1973). Animal managers should provide developing bats an enriched environment that allows for exploration of novel items, play, opportunities for physical testing and flight, as well as a nurturing social environment. As each generation of captive animals is bred, animal managers must be concerned with not only the physical characteristics of the animal (phenotype) and the genetics (genotype), but also the behavioral repertoire which can be extinguished through generations in captivity (Bukojemsky and Markowitz, 1997). Enrichment should focus on preserving all aspects of specific behavior that the animal is capable of within their captive environment. -

Rousettus Aegyptiacus): Specific Adaptive Feeding Strategies

ONLINE FIRST This is a provisional PDF only. Copyedited and fully formatted version will be made available soon. ISSN: 0015-5659 e-ISSN: 1644-3284 Structural and Functional adaptation of the lingual papillae of the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus): Specific Adaptive feeding Strategies Authors: R. M. Kandyel, M. M.A. Abumandour, S. F. Mahmoud, M. Shukry, N. Madkour, A. El-Mansi, F. A. Farrag DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2021.0042 Article type: Original article Submitted: 2021-02-19 Accepted: 2021-03-28 Published online: 2021-04-28 This article has been peer reviewed and published immediately upon acceptance. It is an open access article, which means that it can be downloaded, printed, and distributed freely, provided the work is properly cited. Articles in "Folia Morphologica" are listed in PubMed. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Structural and functional adaptation of the lingual papillae of the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus): specific adaptive feeding strategies R.M. Kandyel et al., Lingual papillae of Egyptian fruit bat R.M. Kandyel1, M.M.A. Abumandour2, S.F. Mahmoud3, M. Shukry4, N. Madkour2, A. El-Mansi5, 6, F.A. Farrag7 1Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Tanta University, Egypt 2Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt 3Department of Biotechnology, College of Science, Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia 4Department of Physiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kafrelsheikh University, Kafrelsheikh, Egypt 5Biology Department, Faculty of Science, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia 6Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt 7Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kafrelsheikh University, Kafrelsheikh, Egypt Address for correspondence: M.M.A.