Suggested Guidelines for Bat Enrichment Bats in the Wild Have A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cynopterus Minutus, Minute Fruit Bat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2019: T136423A21985433 Scope: Global Language: English Cynopterus minutus, Minute Fruit Bat Assessment by: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. 2019. Cynopterus minutus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T136423A21985433. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019- 3.RLTS.T136423A21985433.en Copyright: © 2019 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Chiroptera Pteropodidae Taxon Name: Cynopterus minutus Miller, 1906 Common Name(s): • English: Minute Fruit Bat Taxonomic Notes: This may be a species complex. -

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-Colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa The adaptation of bats (order Chiroptera) to use and For these reasons, we assessed the seasonality of occupy human dwellings across the planet has created coronavirus (CoV) shedding by the straw-colored intensive bat-human interfaces. Because bats provide fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) by passively collecting 97 important ecosystem services and also host and shed fecal samples on a monthly basis during a entire year zoonotic viruses, these interfaces represent a double in two urban colonies: Accra, Ghana (West Africa) challenge: i) the conservation of bats and their services and Morogoro, Tanzania (East Africa; Fig 1). Sampling and ii) the prevention of viral spillover. collection was conducted under the same trees during Many species of bats have evolved a seasonal life the study period. This species of fruit bat shows a single history that has resulted in the development of specific birth pulse during the year, its colonies show spectacular reproductive and foraging activities during distinctive periodical changes in size, and similarly to other tree- periods of the year. For example, many species mate, roosting megabats, several roosts are located in busy give birth, and nurse during particular and predictable urban centers across sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, times of the year. Moreover, bat migration can produce we concomitantly collected data on the roost sizes predictable variations in colony sizes during a typical and precipitation levels over time, and we established year, from a complete absence of bats to the aggregation the reproductive periods through the year (birth of millions of individuals depending on the season. -

Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy

Searchlight Wind Energy Project FEIS Appendix B 18B Appendix B-4: Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy Page | B Searchlight Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy Searchlight Wind Energy Project Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy Prepared for: Duke Energy Renewables 550 South Tryon Street Charlotte, North Carolina 28202 Prepared by: Tetra Tech EC, Inc. 1750 SW Harbor Way, Suite 400 Portland, OR 97201 November 2012 Searchlight BBCS i October 2012 Searchlight Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Duke Energy Renewables‘ Corporate Policy .......................................................... 6 1.2 Statement of Purpose ............................................................................................ 6 2.0 BACKGROUND AND DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT ............................................. 6 3.0 PROJECT-SPECIFIC REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS .............................................11 3.1 Potential Endangered Species Act-Listed Wildlife Species ...................................11 3.2 Migratory Bird Treaty Act ......................................................................................11 3.3 Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act ..................................................................12 3.4 Nevada State Codes .............................................................................................12 4.0 DECISION FRAMEWORK .............................................................................................12 -

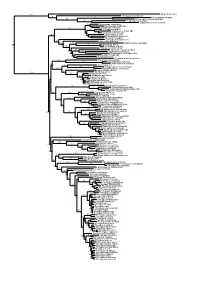

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

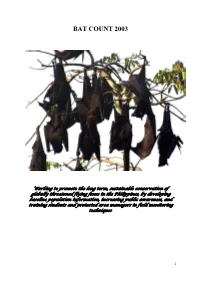

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

Conventional Wisdom on Roosting Behaviour of Australian

Conventional wisdom on roosting behaviour of Australian flying foxes - a critical review, and evaluation using new data Tamika Lunn1, Peggy Eby2, Remy Brooks1, Hamish McCallum1, Raina Plowright3, Maureen Kessler4, and Alison Peel1 1Griffith University 2University of New South Wales 3Montana State University 4Montana State University System April 12, 2021 Abstract 1. Fruit bats (Family: Pteropodidae) are animals of great ecological and economic importance, yet their populations are threatened by ongoing habitat loss and human persecution. A lack of ecological knowledge for the vast majority of Pteropodid bat species presents additional challenges for their conservation and management. 2. In Australia, populations of flying-fox species (Genus: Pteropus) are declining and management approaches are highly contentious. Australian flying-fox roosts are exposed to management regimes involving habitat modification, either through human-wildlife conflict management policies, or vegetation restoration programs. Details on the fine-scale roosting ecology of flying-foxes are not sufficiently known to provide evidence-based guidance for these regimes and the impact on flying-foxes of these habitat modifications is poorly understood. 3. We seek to identify and test commonly held understandings about the roosting ecology of Australian flying-foxes to inform practical recommendations and guide and refine management practices at flying-fox roosts. 4. We identify 31 statements relevant to understanding of flying-fox roosting structure, and synthesise these in the context of existing literature. We then contribute contemporary data on the fine-scale roosting structure of flying-fox species in south-eastern Queensland and north- eastern New South Wales, presenting a 13-month dataset from 2,522 spatially referenced roost trees across eight sites. -

Calculate the Value of Bats

Calculate the Value of Bats Background One of the best ways to persuade people to protect bats is to explain EXPLORATION QUESTION “Why are bats important to our how many insects bats can eat. Scientists have discovered that economy and to our natural some small bats can catch up to 1,000 or more small insects in a world?” single hour. A nursing mother bat eats the most – sometimes catching more than 4,000 insects in a night. MATERIALS Little brown bats (myotis lucifugus) eat a wide variety of insects, Pencils including pests such as mosquitoes, moths, and beetles. If each little Activity Sheets A and B brown bat in your neighborhood had 500 mosquitoes in its evening Calculator (optional) meal, how many would a colony of 100 bats eat? By multiplying the OVERVIEW average number eaten (500) times the number of bats in the colony There are many reasons for (100), we calculate that this colony would eat 50,000 mosquitoes in students to care about bats. They an evening (500 x 100 = 50,000)! are fascinating and beautiful Using a calculator and multiplying 50,000 mosquitoes times 30 days animals. In this activity, students (the average number of days in a month), you can calculate that will use math skills to learn about these same bats could eat 1.5 million mosquitoes in a month (50,000 the ecological and economic x 30 = 1,500,000), not to mention the many other insects they would impacts of bats. Students will also catch! use communication skills to convey the importance of bats to Do bats really eat billions of bugs? our economy and natural world Bracken Cave, just north of San Antonio, Texas, is home to about 20 and the potential effects of White- million Mexican free-tailed bats. -

Final Report on the Project

BP Conservation Programme (CLP) 2005 PROJECT NO. 101405 - BRONZE AWARD WINNER ECOLOGY, DISTRIBUTION, STATUS AND PROTECTION OF THREE CONGOLESE FRUIT BATS FINAL REPORT Patrick KIPALU Team Leader Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement OCPE – ong Kinshasa – Democratic Republic of the Congo E-mail: [email protected] APRIL 2009 1 Table of Content Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. p3 I. Project Summary……………………………………………………………….. p4 II. Introduction…………………………………………………………………… p4-p7 III. Materials and Methods ……………………………………………………….. p7-p10 IV. Results per Study Site…………………………………………………………. p10-p15 1. Pointe-Noire ………………………………………………………….. p10-p12 2. Mayumbe Forest /Luki Reserve……………………………………….. p12-p13 3. Zongo Forest…………………………………………………………... p14 4. Mbanza-Ngungu ………………………………………………………. P15 V. General Results ………………………………………………………………p15-p16 VI. Discussions……………………………………………………………………p17-18 VII. Conclusion and Recommendations……………………………………….p 18-p19 VIII. Bibliography………………………………………………………………p20-p21 Acknowledgements 2 The OCPE (Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement) project team would like to start by expressing our gratefulness and saying thank you to the BP Conservation Program, which has funded the execution of this project. The OCPE also thanks the Van Tienhoven Foundation which provided a further financial support. Without these organisations, execution of the project would not have been possible. We would like to thank specially the BPCP “dream team”: Marianne D. Carter, Robyn Dalzen and our regretted Kate Stoke for their time, advices, expertise and care, which helped us to complete this work, Our special gratitude goes to Dr. Wim Bergmans, who was the hero behind the scene from the conception to the execution of the research work. Without his expertise, advices and network it would had been difficult for the project team to produce any result from this project. -

Are Megabats Flying Primates? Contrary Evidence from a Mitochondrial DNA Sequence

Aust. J. Bioi. Sci., 1988, 41, 327-32 Are Megabats Flying Primates? Contrary Evidence from a Mitochondrial DNA Sequence S. Bennett,A L. J. Alexander,A R. H. CrozierB,c and A. G. MackinlayA,c A School of Biochemistry, University of New South Wales, P.O. Box 1, Kensington, N.S.W. 2033. B School of Biological Science, University of New South Wales, P.O. Box 1, Kensington, N.S.W. 2033. C To whom reprint requests should be addressed. Abstract Bats (Chiroptera) are divided into the suborders Megachiroptera (fruit bats, 'megabats') and Micro chiroptera (predominantly insectivores, 'microbats'). It had been found that megabats and primates share a connection system between the retina and the midbrain not seen in microbats or other eutherian mammals, and challenging but plausible hypotheses were made that (a) bats are diphyletic and (b) megabats are flying primates. We obtained two DNA sequences from the mitochondrion of the fruit bat Pteropus poliocephalus, and performed phylogenetic analyses using the bat sequences in conjunction with homologous Drosophila, mouse, cow and human sequences. Two trees stand out as significantly more likely than any other; neither of these links the bat and human as the closest sequences. These results cast considerable doubt on the hypothesis that megabats are particularly close to primates. Introduction Various phylogenetic schemes based on morphology have linked bats and primates, such as in McKenna's (1975) grandorder Archonta, which also includes the Dermoptera (flying lemurs) and Scandentia (tree shrews). Molecular systematists, using immunological comparisons and amino acid sequences, have found that bats are not placed particularly close to primates, and that they are not diphyletic (Cronin and Sarich 1980; Dene et al. -

A Review of the Pteropus Rufus (É. Geoffroy, 1803) Colonies Within The

ARTICLE IN PRESS - EARLY VIEW MADAGASCAR CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT VOLUME 11 | ISSUE 1 — JUNE 2016 page 1 ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mcd.v11i1.7 A review of the Pteropus rufus (É. Geoffroy, 1803) colonies within the Tolagnaro region of southeast Madagascar – an assessment of neoteric threats and conservation condition Sam Hyde RobertsI, Mark D. JacobsI, Ryan M. ClarkI, Correspondence: Charlotte M. DalyII, Longosoa H. TsimijalyIII, Retsiraiky J. Sam Hyde Roberts RossizelaIII, Samuel T. PrettymanI SEED Madagascar, Studio 7, 1A Beethoven Street, London W10 4LG, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT soit parce qu’elles se sont déplacées suite à des dérangements. We surveyed 10 Pteropus rufus roost sites within the sou- Les effectifs d’une seule colonie semblent avoir diminué de theastern Anosy Region of Madagascar to provide an update on manière significative tandis que ceux de trois autres colonies the areas’ known flying fox population and its conservation status. semblent avoir été maintenus à leur niveau. Notre étude a montré We report on two new colonies from Manambaro and Mandena que l'abondance globale de P. rufus dans la région n’a augmenté and provide an account of the colonies first reported and last as- que d’un pourcent depuis 2006 et que cette augmentation était le sessed in 2006. Currently only a solitary roost site receives any résultat de la protection garantie au dortoir dans la réserve privée formal protection (Berenty) whereas further two colonies rely so- de Berenty. À la lumière d'un décret qui a imposé une période de lely on taboo ‘fady’ for their security. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

BAT-WATCHING SITES of TEXAS Welcome! Texas Happens to Be the Battiest State in the Country

BAT-WATCHING SITES OF TEXAS Welcome! Texas happens to be the battiest state in the country. It is home to 32 of the 47 species of bats found in the United States. Not only does it hold the distinction of having the most kinds of bats, it also boasts the largest known bat colony in the world, Bracken Cave Preserve, near San Antonio, and the largest urban bat colony, Congress Avenue Bridge, in Austin. Visitors from around the world flock BAT ANATOMY to Texas to enjoy public bat-viewing at several locations throughout the state. This guide offers you a brief summary of what each site has to offer as well as directions and contact information. It also includes a list of the bat species currently known to occur within Texas at the end of this publication. Second Finger We encourage you to visit some of these amazing sites and experience the Third Finger wonder of a Texas bat emergence! Fourth Finger Thumb Fifth Finger A Year in the Life Knee of a Mexican Free-tailed Bat Upper Arm Foot Forearm Mexican free-tailed bats (also in mammary glands found under each Tail known as Brazilian free-tailed bats) of her wings. Wrist are the most common bat found The Mexican free-tailed bats’ milk is throughout Texas. In most parts of so rich that the pups grow fast and are Tail Membrane the state, Mexican free-tailed bats ready to fly within four to five weeks of Ear are migratory and spend the winters birth. It is estimated that baby Mexican in caves in Mexico.