Habitat Selection of Endangered and Endemic Large Flying-Foxes in Subic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living with Wildlife - Flying Foxes Fact Sheet No

LIVING WITH WILDLIFE - FLYING FOXES FACT SHEET NO. 0063 Living with wildlife - Flying Foxes What are flying foxes? flying foxes use to mark their territory and to attract females during the mating season. Flying foxes, also known as fruit bats, are winged mammals belonging to the sub-order group of megabats. Unlike the smaller insectivorous microbats, the Do flying foxes carry diseases? animal navigates using their eye sight and smell, as opposed to echolocation, Like most wildlife and pets, flying foxes may carry diseases that can affect and feed on nectar, pollen and fruit. Flying foxes forage from over 100 humans. Australian Bat Lyssavirus can be transmitted directly from flying species of native plants and may supplement this diet with introduced plants foxes to humans. The risk of contracting Lyssavirus is extremely low, with found in gardens, orchards and urban areas. transmission only possible through direct contact of saliva from an infected Of the four species of flying foxes native to mainland Australia, three reside animal with a skin penetrating bite or scratch. in the Gladstone Region. These species include the grey-headed flying fox Flying foxes are natural hosts of the Hendra virus, however, there is no (Pteropus poliocephalus), black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) and little red evidence that the virus can be transmitted directly to humans. It is believed flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus). that the virus is transmitted from flying foxes to horses through exposure to All of these species are protected under the Nature Conservation Act urine or birthing fluids. Vaccination is the most effective way of reducing the 1992 and the grey-headed flying fox is also listed as ‘vulnerable’ under the risk of the virus infecting horses. -

Fruit Bats As Natural Foragers and Potential Pollinators in Fruit Orchard: a Reproductive Phenological Study

Journal of Agricultural Research, Development, Extension and Technology, 25(1), 1-9 (2019) Full Paper Fruit bats as natural foragers and potential pollinators in fruit orchard: a reproductive phenological study Camelle Jane D. Bacordo, Ruffa Mae M. Marfil and John Aries G. Tabora Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Southern Mindanao, Kabacan, Cotabato, Philippines Received: 27 February 2019 Accepted: 10 June 2019 Abstract Family Pteropodidae could consume either fruit or flower parts to sustain their energy requirement. In some species of fruit bats, population growth is sometimes dependent on the food availability and in return bats could be pollinators of certain species of plants. In this study, 152 female bats captured from the Manilkara zapota orchard of the University of Southern Mindanao were examined for their reproductive stages. Lactation of fruit bat species Ptenochirus jagori and Ptenochirus minor were positively correlated with the fruiting of M. zapota. While the lactation of Cynopterus brachyotis, Eonycteris spelaea and Rousettus amplexicaudatus were positively associated with the flowering of M. zapota. Together, thirty M. zapota trees were observed for their generative stage (fruiting or flowering) in 6 months. Based on the canonical correspondence analysis, only P. jagori was considered as the natural forager as its lactating stage coincides with the fruiting peaks and only C. brachyotis and E. spelaea were the potential pollinators since its lactating stage coincides with the flowering peaks ofM. zapota tree. The method in this study can be used to identify potential pollinators and foragers in other fruit trees. Keywords - agroforest, chiropterophily, frugivore, nocturnal, Sapotaceae Introduction pollination process is called chiropterophily. -

Cynopterus Minutus, Minute Fruit Bat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2019: T136423A21985433 Scope: Global Language: English Cynopterus minutus, Minute Fruit Bat Assessment by: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. 2019. Cynopterus minutus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T136423A21985433. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019- 3.RLTS.T136423A21985433.en Copyright: © 2019 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Chiroptera Pteropodidae Taxon Name: Cynopterus minutus Miller, 1906 Common Name(s): • English: Minute Fruit Bat Taxonomic Notes: This may be a species complex. -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia

CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation i ii CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation By Ibnu Maryanto Maharadatunkamsi Anang Setiawan Achmadi Sigit Wiantoro Eko Sulistyadi Masaaki Yoneda Agustinus Suyanto Jito Sugardjito RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) iii © 2019 RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) Cataloging in Publication Data. CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA: Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation/ Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Anang Setiawan Achmadi, Sigit Wiantoro, Eko Sulistyadi, Masaaki Yoneda, Agustinus Suyanto, & Jito Sugardjito. ix+ 66 pp; 21 x 29,7 cm ISBN: 978-979-579-108-9 1. Checklist of mammals 2. Indonesia Cover Desain : Eko Harsono Photo : I. Maryanto Third Edition : December 2019 Published by: RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI). Jl Raya Jakarta-Bogor, Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16911 Telp: 021-87907604/87907636; Fax: 021-87907612 Email: [email protected] . iv PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION This book is a third edition of checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia. The new edition provides remarkable information in several ways compare to the first and second editions, the remarks column contain the abbreviation of the specific island distributions, synonym and specific location. Thus, in this edition we are also corrected the distribution of some species including some new additional species in accordance with the discovery of new species in Indonesia. -

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape As A

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape as a Chiropteran Diversity Hotspot in Sumatra Author(s): Joe Chun-Chia Huang, Elly Lestari Jazdzyk, Meyner Nusalawo, Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Sigit Wiantoro, and Tigga Kingston Source: Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2):413-449. Published By: Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/150811014X687369 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3161/150811014X687369 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2): 413–449, 2014 PL ISSN 1508-1109 © Museum and Institute of Zoology PAS doi: 10.3161/150811014X687369 A recent -

WIAD CONSERVATION a Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity

WIAD CONSERVATION A Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity WIAD CONSERVATION A Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 2 Ohu Map ...................................................................................................................................... 3 History of WIAD Conservation ...................................................................................................... 4 WIAD Legends .............................................................................................................................. 7 The Story of Julug and Tabalib ............................................................................................................... 7 Mou the Snake of A’at ........................................................................................................................... 8 The Place of Thunder ........................................................................................................................... 10 The Stone Mirror ................................................................................................................................. 11 The Weather Bird ................................................................................................................................ 12 The Story of Jelamanu Waterfall ......................................................................................................... -

Phenology of Ficus Variegata in a Seasonal Wet Tropical Forest At

Joumalof Biogeography (I1996) 23, 467-475 Phenologyof Ficusvariegata in a seasonalwet tropicalforest at Cape Tribulation,Australia HUGH SPENCER', GEORGE WEIBLENI 2* AND BRIGITTA FLICK' 'Cape TribulationResearch Station, Private Mail Bag5, Cape Tribulationvia Mossman,Queensland 4873, Australiaand 2 The Harvard UniversityHerbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue,Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA Abstract. We studiedthe phenologyof 198 maturetrees dioecious species, female and male trees initiatedtheir of the dioecious figFicus variegataBlume (Moraceae) in a maximalfig crops at differenttimes and floweringwas to seasonally wet tropical rain forestat Cape Tribulation, some extentsynchronized within sexes. Fig productionin Australia, from March 1988 to February 1993. Leaf the female (seed-producing)trees was typicallyconfined productionwas highlyseasonal and correlatedwith rainfall. to the wet season. Male (wasp-producing)trees were less Treeswere annually deciduous, with a pronouncedleaf drop synchronizedthan femaletrees but reacheda peak level of and a pulse of new growthduring the August-September figproduction in the monthsprior to the onset of female drought. At the population level, figs were produced figproduction. Male treeswere also morelikely to produce continuallythroughout the study but there were pronounced figscontinually. Asynchrony among male figcrops during annual cyclesin figabundance. Figs were least abundant the dry season could maintainthe pollinatorpopulation duringthe early dry period (June-September)and most under adverseconditions -

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)

Chapter 6 Phylogenetic Relationships of Harpyionycterine Megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) NORBERTO P. GIANNINI1,2, FRANCISCA CUNHA ALMEIDA1,3, AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT After almost 70 years of stability following publication of Andersen’s (1912) monograph on the group, the systematics of megachiropteran bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) was thrown into flux with the advent of molecular phylogenetics in the 1980s—a state where it has remained ever since. One particularly problematic group has been the Austromalayan Harpyionycterinae, currently thought to include Dobsonia and Harpyionycteris, and probably also Aproteles.Inthis contribution we revisit the systematics of harpyionycterines. We examine historical hypotheses of relationships including the suggestion by O. Thomas (1896) that the rousettine Boneia bidens may be related to Harpyionycteris, and report the results of a series of phylogenetic analyses based on new as well as previously published sequence data from the genes RAG1, RAG2, vWF, c-mos, cytb, 12S, tVal, 16S,andND2. Despite a striking lack of morphological synapomorphies, results of our combined analyses indicate that Boneia groups with Aproteles, Dobsonia, and Harpyionycteris in a well-supported, expanded Harpyionycterinae. While monophyly of this group is well supported, topological changes within this clade across analyses of different data partitions indicate conflicting phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial partition. The position of the harpyionycterine clade within the megachiropteran tree remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, biogeographic patterns (vicariance-dispersal events) within Harpyionycterinae appear clear and can be directly linked to major biogeographic boundaries of the Austromalayan region. The new phylogeny of Harpionycterinae also provides a new framework for interpreting aspects of dental evolution in pteropodids (e.g., reduction in the incisor dentition) and allows prediction of roosting habits for Harpyionycteris, whose habits are unknown. -

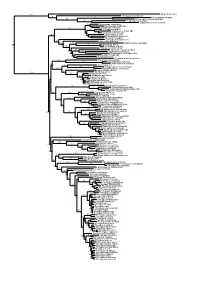

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Rainforest Disturbance Affects Population Density of the Northern Cassowary Casuarius Unappendiculatus in Papua, Indonesia

Rainforest disturbance affects population density of the northern cassowary Casuarius unappendiculatus in Papua, Indonesia M ARGARETHA P ANGAU-ADAM,MICHAEL M ÜHLENBERG and M ATTHIAS W ALTERT Abstract Nominally protected areas in Papua are under and human population growth are leading to high rates threat from encroachment, logging and hunting. The of deforestation and forest conversion. Besides disturbance northern cassowary Casuarius unappendiculatus is the from logging, large-scale oil palm plantations are the pri- largest frugivore of the lowland rainforest of New Guinea mary cause of the loss of lowland forest in Papua (Frazier, and is endemic to this region, and therefore it is an 2007). A number of conservation areas and protection important conservation target and a potential flagship forests have been established in this region (de Fretes, 2007) species. We investigated effects of habitat degradation on the but agricultural encroachment, illegal logging and hunting species by means of distance sampling surveys of 58 line by immigrants and local communities are common. As in transects across five distinct habitats, from primary forest to other parts of the tropics, local extinction of forest avifauna forest gardens. Estimated cassowary densities ranged from following forest fragmentation and extensive forest clearing −2 14.1 (95%CI9.2–21.4) birds km in primary forest to 1.4 is to be expected (Kattan et al., 1994; Castelletta et al., 2000; −2 (95%CI0.4–5.6) birds km in forest garden. Density Waltert et al., 2004). Large forest birds such as cassowaries estimates were intermediate in unlogged but hunted natural (Casuarius spp.) are particularly likely to disappear if forest and in . -

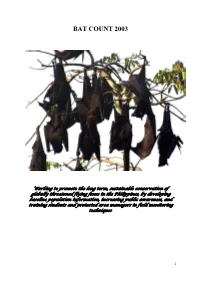

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area.