Exploitation of Bats for Bushmeat and Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living with Wildlife - Flying Foxes Fact Sheet No

LIVING WITH WILDLIFE - FLYING FOXES FACT SHEET NO. 0063 Living with wildlife - Flying Foxes What are flying foxes? flying foxes use to mark their territory and to attract females during the mating season. Flying foxes, also known as fruit bats, are winged mammals belonging to the sub-order group of megabats. Unlike the smaller insectivorous microbats, the Do flying foxes carry diseases? animal navigates using their eye sight and smell, as opposed to echolocation, Like most wildlife and pets, flying foxes may carry diseases that can affect and feed on nectar, pollen and fruit. Flying foxes forage from over 100 humans. Australian Bat Lyssavirus can be transmitted directly from flying species of native plants and may supplement this diet with introduced plants foxes to humans. The risk of contracting Lyssavirus is extremely low, with found in gardens, orchards and urban areas. transmission only possible through direct contact of saliva from an infected Of the four species of flying foxes native to mainland Australia, three reside animal with a skin penetrating bite or scratch. in the Gladstone Region. These species include the grey-headed flying fox Flying foxes are natural hosts of the Hendra virus, however, there is no (Pteropus poliocephalus), black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) and little red evidence that the virus can be transmitted directly to humans. It is believed flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus). that the virus is transmitted from flying foxes to horses through exposure to All of these species are protected under the Nature Conservation Act urine or birthing fluids. Vaccination is the most effective way of reducing the 1992 and the grey-headed flying fox is also listed as ‘vulnerable’ under the risk of the virus infecting horses. -

Cynopterus Minutus, Minute Fruit Bat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2019: T136423A21985433 Scope: Global Language: English Cynopterus minutus, Minute Fruit Bat Assessment by: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. 2019. Cynopterus minutus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T136423A21985433. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019- 3.RLTS.T136423A21985433.en Copyright: © 2019 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Chiroptera Pteropodidae Taxon Name: Cynopterus minutus Miller, 1906 Common Name(s): • English: Minute Fruit Bat Taxonomic Notes: This may be a species complex. -

EAZA Bushmeat Campaign

B USHMEAT | R AINFOREST | T IGER | S HELLSHOCK | R HINO | M ADAGASCAR | A MPHIBIAN | C ARNIVORE | A PE EAZA Conservation Campaigns EAZA Bushmeat Over the last ten years Europe’s leading zoos and aquariums have worked together in addressing a variety of issues affecting a range of species and Campaign habitats. EAZA’s annual conservation campaigns have raised funds and promoted awareness amongst 2000-2001 millions of zoo visitors each year, as well as providing the impetus for key regulatory change. | INTRODUCTION | The first of EAZA's annual conservation campaigns addressed the issue of the unsustainable and illegal hunting and trade of threatened wildlife, in particular the great apes. Bushmeat is a term commonly used to describe the hunting and trade of wild meat. For the Bushmeat Campaign EAZA collaborated with the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) as an official partner in order to enhance the chances of a successful campaign. The Bushmeat Campaign can be regarded as the ‘template campaign’ for the EAZA conservation campaigns that followed over the subsequent ten years. | CAMPAIGN AIMS | Through launching the Bushmeat Campaign EAZA hoped to make a meaningful contribution to the conservation of great apes in the wild, particularly in Africa, over the next 20 to 50 years. The bushmeat trade was (and still is) a serious threat to the survival of apes in the wild. Habitat loss and deforestation have historically been the major causal factors for declining populations of great apes, but experts now agree that the illegal commercial bushmeat trade has surpassed habitat loss as the primary threat to ape populations. -

Genetic Diversity of the Chaerephon Leucogaster/Pumilus Complex From

Genetic diversity of the Chaerephon leucogaster/pumilus complex from mainland Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands Theshnie Naidoo 202513500 Submitted in fulfillment of the academic Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Life Sciences, Westville Campus, University of KwaZulu – Natal, Durban. NOVEMBER 2013 Supervisory Committee Prof. JM. Lamb Dr. MC. Schoeman Dr. PJ. Taylor Dr. SM. Goodman i ABSTRACT Chaerephon (Dobson, 1874), an Old World genus belonging to the family Molossidae, is part of the suborder Vespertilioniformes. Members of this genus are distributed across mainland Africa (sample sites; Tanzania, Yemen, Kenya, Botswana, South Africa and Swaziland), its offshore islands (Zanzibar, Pemba and Mozambique Island), Madagascar and the surrounding western Indian Ocean islands (Anjouan, Mayotte, Moheli, Grande Comore, Aldabra and La Reunion). A multifaceted approach was used to elucidate the phylogenetic and population genetic relationships at varying levels amongst these different taxa. Working at the subspecific level, I analysed the phylogenetics and phylogeography of Chaerephon leucogaster from Madagascar, based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and control region sequences. Cytochrome b genetic distances among C. leucogaster samples were low (maximum 0.35 %). Genetic distances between C. leucogaster and C. atsinanana ranged from 1.77 % to 2.62 %. Together, phylogenetic and distance analyses supported the classification of C. leucogaster as a separate species. D-loop data for C. leucogaster samples revealed significant but shallow phylogeographic structuring into three latitudinal groups (13º S, 15 - 17º S, 22 - 23º S) showing exclusive haplotypes which correlated with regions of suitable habitat defined by ecological niche modelling. Population genetic analysis of D-loop sequences indicated that populations from Madagascar have been expanding since 5 842 - 11 143 years BP. -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia

CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation i ii CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation By Ibnu Maryanto Maharadatunkamsi Anang Setiawan Achmadi Sigit Wiantoro Eko Sulistyadi Masaaki Yoneda Agustinus Suyanto Jito Sugardjito RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) iii © 2019 RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) Cataloging in Publication Data. CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA: Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation/ Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Anang Setiawan Achmadi, Sigit Wiantoro, Eko Sulistyadi, Masaaki Yoneda, Agustinus Suyanto, & Jito Sugardjito. ix+ 66 pp; 21 x 29,7 cm ISBN: 978-979-579-108-9 1. Checklist of mammals 2. Indonesia Cover Desain : Eko Harsono Photo : I. Maryanto Third Edition : December 2019 Published by: RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI). Jl Raya Jakarta-Bogor, Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16911 Telp: 021-87907604/87907636; Fax: 021-87907612 Email: [email protected] . iv PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION This book is a third edition of checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia. The new edition provides remarkable information in several ways compare to the first and second editions, the remarks column contain the abbreviation of the specific island distributions, synonym and specific location. Thus, in this edition we are also corrected the distribution of some species including some new additional species in accordance with the discovery of new species in Indonesia. -

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-Colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa The adaptation of bats (order Chiroptera) to use and For these reasons, we assessed the seasonality of occupy human dwellings across the planet has created coronavirus (CoV) shedding by the straw-colored intensive bat-human interfaces. Because bats provide fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) by passively collecting 97 important ecosystem services and also host and shed fecal samples on a monthly basis during a entire year zoonotic viruses, these interfaces represent a double in two urban colonies: Accra, Ghana (West Africa) challenge: i) the conservation of bats and their services and Morogoro, Tanzania (East Africa; Fig 1). Sampling and ii) the prevention of viral spillover. collection was conducted under the same trees during Many species of bats have evolved a seasonal life the study period. This species of fruit bat shows a single history that has resulted in the development of specific birth pulse during the year, its colonies show spectacular reproductive and foraging activities during distinctive periodical changes in size, and similarly to other tree- periods of the year. For example, many species mate, roosting megabats, several roosts are located in busy give birth, and nurse during particular and predictable urban centers across sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, times of the year. Moreover, bat migration can produce we concomitantly collected data on the roost sizes predictable variations in colony sizes during a typical and precipitation levels over time, and we established year, from a complete absence of bats to the aggregation the reproductive periods through the year (birth of millions of individuals depending on the season. -

African Bat Conservation News

Volume 35 African Bat Conservation News August 2014 ISSN 1812-1268 © ECJ Seamark, 2009 (AfricanBats) Above: A male Cape Serotine Bat (Neoromicia capensis) caught in the Chitabi area, Okavango Delta, Botswana. Inside this issue: Research and Conservation Activities Presence of paramyxo and coronaviruses in Limpopo caves, South Africa 2 Observations, Discussions and Updates Recent changes in African Bat Taxonomy (2013-2014). Part II 3 Voucher specimen details for Bakwo Fils et al. (2014) 4 African Chiroptera Report 2014 4 Scientific contributions Documented record of Triaenops menamena (Family Hipposideridae) in the Central Highlands of 6 Madagascar Download and subscribe to African Bat Conservation News published by AfricanBats at: www.africanbats.org The views and opinions expressed in articles are no necessarily those of the editor or publisher. Articles and news items appearing in African Bat Conservation News may be reprinted, provided the author’s and newsletter refer- ence are given. African Bat Conservation News August 2014 vol. 35 2 ISSN 1812-1268 Inside this issue Continued: Recent Literature Conferences 7 Published Books / Reports 7 Papers 7 Notice Board Conferences 13 Call for Contributions 13 Research and Conservation Activities Presence of paramyxo- and coronaviruses in Limpopo caves, South Africa By Carmen Fensham Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, 0001, Republic of South Africa. Correspondence: Prof. Wanda Markotter: [email protected] Carmen Fensham is a honours excrement are excised and used to isolate any viral RNA that student in the research group of may be present. The identity of the RNA is then determined Prof. -

Empty Forests, Empty Stomachs? Bushmeat and Livelihoods in the Congo and Amazon Basins

International Forestry Review Vol.13(3), 2011 355 Empty forests, empty stomachs? Bushmeat and livelihoods in the Congo and Amazon Basins R. NASI1, A. TABER1 and N. VAN VLIET2 1Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Jalan CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindang Barang, Bogor 16680, Indonesia 2Department of Geography and Geology, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 10, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark Email: [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected] SUMMARY Protein from forest wildlife is crucial to rural food security and livelihoods across the tropics. The harvest of animals such as tapir, duikers, deer, pigs, peccaries, primates and larger rodents, birds and reptiles provides benefits to local people worth millions of US$ annually and represents around 6 million tonnes of animals extracted yearly. Vulnerability to hunting varies, with some species sustaining populations in heavily hunted secondary habitats, while others require intact forests with minimal harvesting to maintain healthy populations. Some species or groups have been characterized as ecosystem engineers and ecological keystone species. They affect plant distribution and structure ecosystems, through seed dispersal and predation, grazing, browsing, rooting and other mechanisms. Global attention has been drawn to their loss through debates regarding bushmeat, the “empty forest” syndrome and their ecological importance. However, information on the harvest remains fragmentary, along with understanding of ecological, socioeconomic and cultural dimensions. Here we assess the consequences, both for ecosystems and local livelihoods, of the loss of these species in the Amazon and Congo basins. Keywords: bushmeat, livelihoods, forest, Amazon, Congo Forêts vides, estomacs vides? Viande de brousse et condition de vie dans les bassins du Congo et de l’Amazone. -

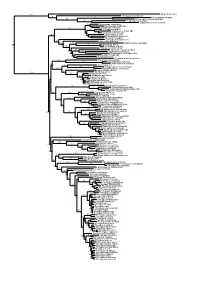

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Priority-Setting for Philippine Bats Using Practical Approach to Guide Effective Species Conservation and Policy-Making in the Anthropocene

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 30 (1): 74–83, 2019 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it doi:10.4404/hystrix–00172-2019 Research Article Priority-setting for Philippine bats using practical approach to guide effective species conservation and policy-making in the Anthropocene Krizler Cejuela Tanalgo1,2,3,4,∗, Alice Catherine Hughes1,3 1Landscape Ecology Group, Centre for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla, Yunnan Province 666303, People’s Republic of China 2International College, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, People’s Republic of China 3Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla, Yunnan Province 666303, People’s Republic of China 4Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Southern Mindanao, Kabacan 9407, North Cotabato, the Republic of the Philippines Keywords: Abstract asian tropics endemism National level approaches to the development and implementation of effective conservation policy forest loss and practice are often challenged by limited capacity and resources. Developing relevant and hunting achievable priorities at the national level is a crucial step for effective conservation. The Philip- islands pine archipelago includes over 7000 islands and is one of only two countries considered both a oil palm global biodiversity hotspot and a megadiversity country. Yet, few studies have conducted over- arching synthesis for threats and conservation priorities of any species group. As bats make up a Article history: significant proportion of mammalian diversity in the Philippines and fulfil vital roles to maintain Received: 01/19/2019 ecosystem health and services we focus on assessing the threats and priorities to their conserva- Accepted: 24/06/2019 tion across the Philippines. -

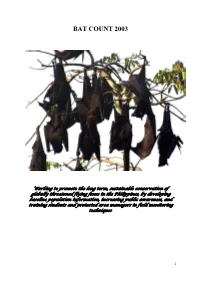

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area.